The toll Steam Trading Cards take on indies

You'd think that Steam Trading Cards are harmless. It's a relatively simple idea: play a participating game on Steam, and within a few hours, a series of four or five trading cards (usually out of a total of eight) will drop at random intervals. Since you can't get all the cards yourself, you'll need to trade with friends or buy them on the Steam Market to complete the set. Once you have all a game's cards, you can craft a badge, which will compensate you a random emoticon and background related to the game. What could be so bad about that? Plenty, if you're a small indie developer that takes pride in their work.

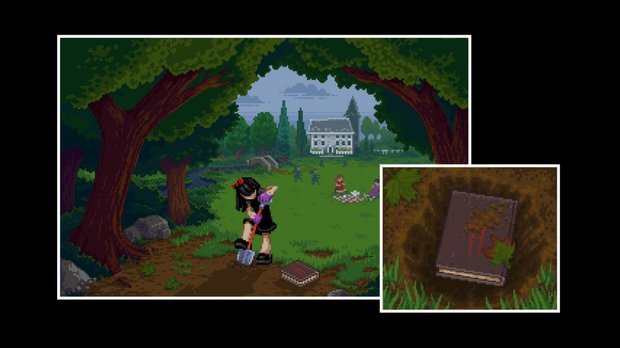

Meet Miguel Sternberg, a veteran pixel artist and game designer with a penchant for cephalopods. He makes up half the team at Spooky Squid Games, best known for their hardcore 2D platformer They Bleed Pixels. In it, you play as a girl with purple skin and lobster-like pincers, chopping your way through Cthulhu-like enemies and vaulting over innumerable deathtraps. It was one of the first games to incorporate Steam Trading Cards during the beta--a process that Sternberg describes as "fairly informal and simple, as these sorts of things go."

There wasn't much barrier to entry. "[Valve] sent a bulk email to all the developers, saying 'Here's how the cards work; if you want to do them, this is what we need from you,'" says Sternberg. "It was very much open to individual developers whether they wanted to implement them or not." Some guidelines do exist regarding the badge bonuses: you can only make a maximum of 10 emoticons tied to your game, and as a developer, you're required to make a few of them Uncommon and one of them Rare. Foil versions of each card will drop at random, kicking up the rarity of some cards even higher.

"You can't just make everything easy to get, which I think is unfortunate, but understandable," says Sternberg. Like so many collectibles, you'll need to coordinate with your buddies--or strangers--if you want any hope of catching 'em all. Sternberg's no fool--"I get that what they want to do is get people trading," he says. "I'd love it if we could just sell backgrounds and icon packs to people directly. [But] I know the reason this stuff's there is because Valve wants people to get more invested in the community and Market."

To gather up all the emoticons and profile backgrounds for any given game, you'd have to craft multiple badges, a feat that can only realistically be done by rummaging through the Steam Market. "I like the idea of having little artifacts associated with the game, and stuff that people can use in the community," says Sternberg. "But the whole collector/psychological hook stuff I kind of wish wasn't there. What I worry is that it's the same sort of thing that Facebook games and casinos have. You get whales: people who are massively invested [in trading] and spend way more money than they necessarily have on it."

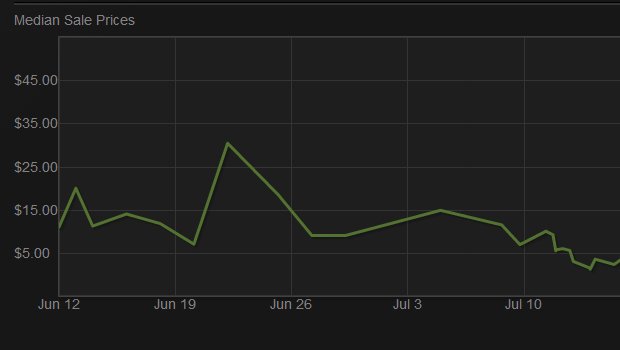

Market history for the Foil "Squidy Thing" card. Each point on the graph marks a successful sale.

The addictive nature of card collecting fuels the Market, where supply and demand play out as clear as day. The most popular Steam Card games, like Dota 2 or Team Fortress 2, have players in droves, and the surplus of cards drives the prices way down. But for lesser-known indies, the comparatively tiny playerbase means cards are few and far between, and savvy sellers know they can charge more for them. Sternberg recalls seeing They Bleed Pixels cards listed on the Market for over $10; foil cards have sold for as much as 30 bucks. The game itself costs $9.99.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

When people are paying more for a valueless trinket than they are for the actual work that spawned them, it can be devastating to a developer's ego. "Honestly, it's a little bit depressing to see the cards selling more than the game is," laments Sternberg. "That to me feels kind of broken." The worst case scenario is that your labor of love, the game you worked hard to create, is being played for profit instead of pleasure by the majority of its users. "You do hope that if somebody is buying [They Bleed Pixels], they're buying it to play and enjoy the game," says Sternberg. "The cards throw this weird psychological thing in the way of that."

That being said, there are plenty of upsides, and Steam Trading Cards have done a lot for the success of the game. "I've definitely found more people buying it since we've added Steam Cards," says Sternberg. "Our day-to-day sales jumped to roughly double, and maintained being double what they were before, ever since we got the cards." That's great news, especially for a game like They Bleed Pixels, where sales have been primarily driven by half-off flash deals.

Crafty gamers can also use Trading Cards to front the bill for cheaper indie experiences. "I think some people were buying it for the cards--not because they wanted the cards or anything to do with them, but because it meant that they could sell them and the game basically cost them much less," says Sternberg. "I definitely saw a few people on my Twitter feed who were like 'Bought this game, sold the cards. Game basically cost me nothing.' And I'm totally OK with that, because we make just as much money if they sell the cards or don't. If it means more people getting the game--especially people who are in a low income situation--I'm OK with that part for sure."

But the fact remains that with digital items, there will always be those who are mindlessly collecting and selling them for profit; you might refer to them as farmers. And the increased exposure that comes with Card functionality can be a double-edged sword. "Particularly for the people whose games are not wildly, massively successful, I can see there being a lot of pressure to add cards from a financial standpoint," says Sternberg. Yes, more people notice the existence of your game--but from the creative standpoint, if people are buying your game just to idle for some virtual cards, your efforts were all but meaningless.

It's not that Sternberg thinks Steam Trading Cards are so terrible. But if more and more developers catch on to how much cards can boost profits, adding them might start to feel like a requirement. Sternberg would rather spend time polishing the game design and ironing out bugs, instead of trying to craft the most desirable set of badge rewards. "I would like to have the choice economically to decide, per game, whether we need to do it," says Sternberg. "I think it would be terrible if I felt we always had to, no matter what, for our game to be successful."

Lucas Sullivan is the former US Managing Editor of GamesRadar+. Lucas spent seven years working for GR, starting as an Associate Editor in 2012 before climbing the ranks. He left us in 2019 to pursue a career path on the other side of the fence, joining 2K Games as a Global Content Manager. Lucas doesn't get to write about games like Borderlands and Mafia anymore, but he does get to help make and market them.