Return to Silent Hill is a disaster, and further proof that Hollywood still hasn't figured out how to adapt horror video games

Often, in Silent Hill 2, you need to find an item that’s inside a toilet. Typically, they're keys, or fragments of puzzle pieces, things that you need to progress the story forward. In other words, Silent Hill 2 is a game that forces you into uncomfortable or grim situations; you have to press a button multiple times to make James Sunderland dig through the detritus, muck, and gross liquids to dig out the items you need.

The point of this isn’t just for the game to gross you out, but to force agency onto you. In order to move forward, you need to make unpleasant choices. This is often at the core of how horror works in video games: you, the player, actively respond to – and sometimes create – horrific situations. And this seems to be one of the major reasons that horror games seem to struggle when it comes to being adapted for the big screen.

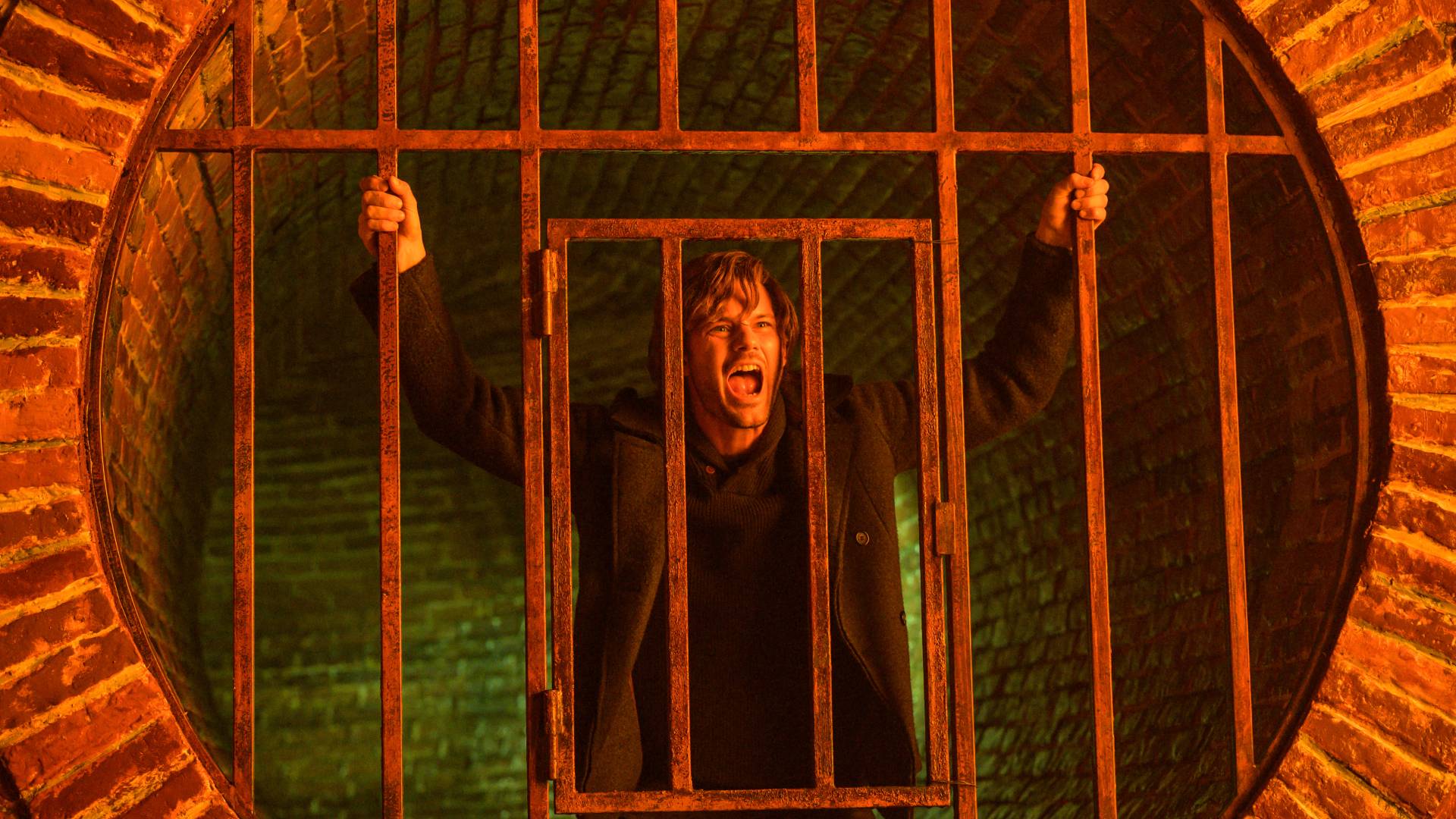

Return to Silent Hill, a new film that attempts to adapt the classic horror game, is a bad adaptation. It is also, unfortunately, a bad film. It's tempting to lay some of this at the feet of a script that seems to ignore any real fidelity to the source material – there are several character and plot choices that are baffling – but more than that, something that doesn’t seem to grasp the spirit of Silent Hill 2, and of horror games more generally: that the point of the horror comes from the active ways in which it happens. And yet, Return to Silent Hill presents a cast of characters who are enormously passive; even James himself seems to experience the events in the passive voice.

As a game, Silent Hill 2 is about forcing the player deep into not only an unsettling physical location, but a mental one as well, as the town distorts through James’s increasingly damaged psyche. And there are moments of this in the film: as it reaches the climax, everything around James becomes almost literally hellish. And the film’s monsters are interesting in their design and grotesque physicality; the first appearance of Pyramid Head can send a jolt through you. But these aren’t the things that make Silent Hill 2 so unique, or so beloved.

Missing the mark

Silent Hill 2 is about sharing a physical and psychological space with someone who’s deeply damaged and difficult to understand. But the film insists on cutting away from him, spelling it all out through phone calls with a therapist talking to James about grief and his inability to let go of the past.

Often, the game is just James, alone, wandering through the town of Silent Hill. And while this might not work on film – there needs to be dialogue, more characters, other ways to advance the plot beyond watching someone solve puzzles on screen for hours – the adaptation is always at risk of undermining what makes the game work so well.

Some of this is the problem of adaptation itself. The recent remake of Silent Hill 2 can take around sixteen hours to beat, a lot of material to condense into a film that’s under two hours. It’s no wonder then, that some of the film’s most iconic moments and important characters seem to appear in order to have a moment in the spotlight, only to disappear moments later.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

A pivotal scene with Angela is recreated well enough visually, as she and James face off in a room where one wall is dominated by a large mirror, but the substance of it is lost in translation. Moments and ideas from the game are adapted onto the screen, but not in a way that seems to cohere around the ideas that animate the game itself – it’s uglier, more unpleasant than the incredibly clean sheen that Return to Silent Hill has.

Surface deep

Pure fidelity, then, seems to be the wrong thing to ask for. After all, Paul W.S. Anderson’s Resident Evil films were, warts and all, successful, and they centred a character created specifically for the films. And yet, when the cinematic adaptation of Konami’s survival horror franchise was rebooted with the 2021 film Welcome to Raccoon City, major characters from both of the first two games feature – everyone from Leon and Claire to Jill and Wesker; Ada even makes a post-credits cameo. Welcome to Raccoon City has fanservice to spare in the ways it recreates key locations and scenes from the first two games, but it all ends up feeling a little hollow, as if the crew were simply smashing their action figures together and hoping that would be enough.

There are moments where Return to Silent Hill does the same thing: iconic images from the game are recreated: James looking at his distorted reflection in a grimy mirror, the labyrinth, James hiding in a closet, staring out at the slats when he first encounters Pyramid Head. But they don’t exist in service of anything other than a reminder that what you’re watching is, nominally at least, an adaptation of Silent Hill 2.

It’s ironic, then, that while Silent Hill 2 is difficult to adapt because of its density, something like Five Nights at Freddy’s 2 flounders because the game is so often much more spare than a film could ever be. There's a mechanical simplicity to Five Nights as a game, where you cycle between cameras in order to keep an eye on the sinister animatronics that come to life at night. But this would never work on film, so the 2023 film is full of extraneous plot points, big themes about trauma, and a seemingly endless number of dream sequences and flashbacks.

Five Nights works as a game because of its simplicity, because of where it places the player – constantly on edge, constantly having to make choices to try and keep themselves safe – and the moments where the film succeeds aren't the ones that feel like fan service, or even ones where the original conceits for the adaptation manage to do something special (because, unfortunately, they never really do). Instead, Five Nights really comes to life when it understands what makes the game get under a player's skin: the grainy security camera footage, the uncertainty of what might be lurking around the corner. It's these moments that capture the spirit of the game, rather than anything as dense as plot or lore, that are able to make it work in a new form.

Breaking free

These adaptations, then, seem to fall apart because of a core misunderstanding of what people want from them. It could never be about beat-for-beat recreations of the plot and its images – either because the source material is too long, like Silent Hill 2, or too short, like Five Nights – or about the dopamine rush of recognition that comes from fan service. It’s about understanding what makes these stories unique; what it is about them that's worth bringing forward into a new medium.

And, for Silent Hill 2, that so often means a sense of discomfort and dread, the idea that you're making impossible decisions because they're the only ones available to you. And yet, Return to Silent Hill presents an incredibly passive version of James. By the film's ending, it so fundamentally misunderstands the source material that it offers James something that the game never would: absolution, the idea that he simply doesn't need to make a choice at all.

These adaptations seem to be at war with themselves. On the one hand, they often go out of their way to feel as much like the games as possible by recreating scenes and locations from their source material in as much detail as possible (in Welcome to Raccoon City, the camera travels through the Racoon Police Department station with reverence once Leon first steps inside and turns on the light), and yet they'll often throw some of the most important parts of a game's story out the window in the process of adapting them – which is what Return to Silent Hill does with all of its female characters.

These stories are often, in one way or another, difficult to adapt. And so the films seem to respond to that by not committing to any real kind of adaptation – neither their own thing, nor a meaningful recreation of the original. Until filmmakers are able to grasp not just the surface-level ideas of these stories, but what makes them special, then horror games will still be consigned to being bizarre, frustrating oddities.

Return to Silent Hill is in cinemas now. For more, check out our guide to the upcoming video game movies heading your way.

Sam Moore is a freelance culture writer who loves action movies, The Simpsons, and Paul Thomas Anderson - dreaming of how all three can crossover. He was written for the likes of GQ, BBC, Financial Times, and The Guardian and profiled stars as varied as Michelle Yeoh, Stephen Graham, and Stevie Van Zandt. In his spare time, he can be found playing Pac -Man.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.