The best part of Silent Hill f is also my favorite from Bloodborne, and it has nothing to do with "Soulslike" combat

Opinion | It's not always a haunted doll, but it's usually a haunted doll

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

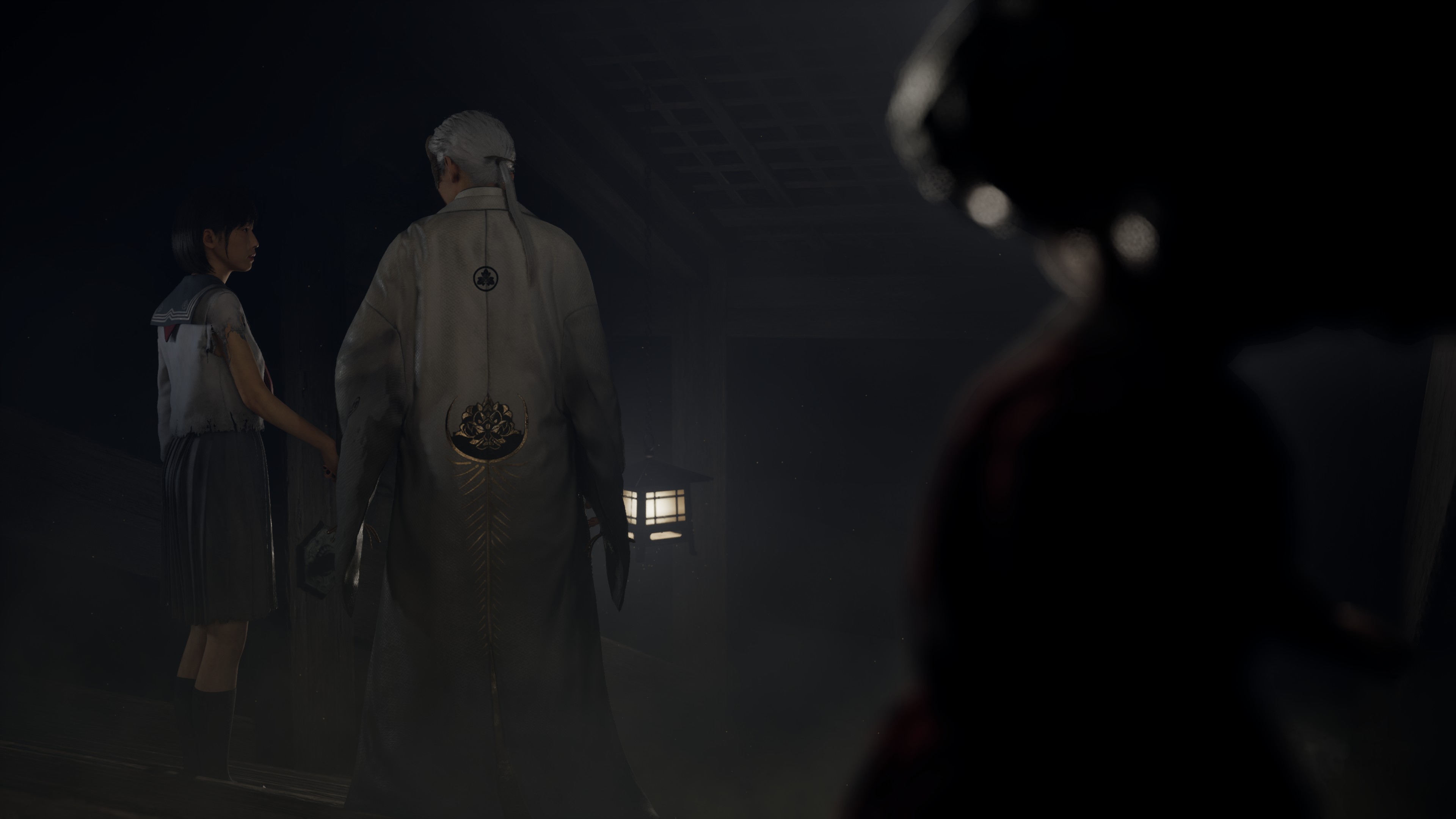

God is in everything, people say. In Silent Hill f, there's a god inside a doll with red apple cheeks. As soon as I met her at the start of Konami's survival horror game, which is sometimes contemptibly being called "Soulslike" because of its calculated but awkward combat, I began to think of my favorite shepherd through the Underworld – the Doll from FromSoftware's 2015 cosmic terror Bloodborne.

In both games, the doll is a guide through each protagonist's nightmare, able to see through artifice because she herself is artificial. I think with her help, Silent Hill f is more admirably Soulslike in its excellent, open-ended narrative.

(Major spoilers for both Silent Hill f and Bloodborne ahead).

It doesn't seem like the doll in Silent Hill f has a name. She starts the game wobbling in schoolgirl Hinako's frustrated hands – Hinako is remembering when no one wanted to play with her, she was too boyish. The doll's blonde curls and red ribbon are celluloid and therefore immune to the abuse, but the glint in her lidless eyes seems… accusatory.

A real doll

Those who make it to the Tsukumogami boss fight in Silent Hill f's New Game+ will eventually realize the doll – which stands spotless in a red dress at the center of the livid spirit's chest – is only a vessel; in Japanese folklore, tsukumogami are overlooked household objects that become calamitous yokai after reaching their 100th birthday. Hinako, who always preferred to run with the boys, never did pay her dolly enough attention.

But, like in Dark Souls, Bloodborne, and Elden Ring, the feminist narrative that writer Ryukishi07 gives Silent Hill f is mostly buried in notes or items. Because of this, the game's story is really determined by your interpretation of your likely limited experience, as if you were reading a fable with all the words about princesses redacted.

So, rather than the doll's seemingly confirmed existence as a two-face god. I'm more interested in the good advice the doll gives me through most of Silent Hill f's runtime. Hinako's bitchy friends, who gossip and wish her a lonely death, certainly won't do it.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Close companion

This is the way Silent Hill f's doll reminds me of The Doll in Bloodborne, a woman-sized porcelain doll who helps you level up. She's also been overlooked; while she was created to be the Gehrman, the First Hunter's gorgeous companion, The Doll has been left alone inside the Hunter's Dream to cry crystal tears and wonder why she exists.

It's a lot like being a teenager without a father who understands you (speaking from experience), which is the existential predicament Hinako finds herself in. Playing Silent Hill f from her perspective, I teeter between understanding what people think of me, what they want me to do with my body (slice off the arm, give it to the man in the fox mask), and blank denial.

My dolly has no time for it. I keep finding her watching me from random corners. "Beware Rinko," she scratches into the floor before Rinko shoves me down the stairs. "Don't trust the Fox Mask," she scrawls in sloppy ink. "Remember! Your name is Shimizu Hinako!" Other times, she just watches me, her stubby toddler arms stretched toward me like branches looking for the sun.

All dolls go to heaven

This doll and The Doll in Bloodborne have been left behind. Blessed or cursed with sentience, they know they've been left behind, and what they represent – a version of femininity determined by their maker, the innocence required to love something that isn't "real" – collects dust right alongside them, for both good and bad.

Bad: Hinako's rival Rinko owns many wooden Kokeshi dolls, and in the hands of this girl who punishes Hinako for not adhering perfectly to her standards of young womanhood, dolls seem rigid. Oppressive, even.

Good: Hinako's yellow-haired doll knows its owner has no interest in conforming and, let's be honest, as a 100-year-old ghost thing, it doesn't exactly "conform" either. This doll urges Hinako to trust herself, much how Bloodborne's Doll rewards the player's agency with leveling-up despite its angst over its own abandonment. In this way, dolls represent humanity – a humanity that's so idealistic, it might as well be fake. It's just a doll. Nonetheless, a doll is infinitely more resistant to pain than the player character of either Silent Hill f or Bloodborne. It can withstand the horrors driving each game's protagonist to frenzied despair.

So, having now played both games multiple times, I'm still a little thrilled when I re-experience the moment they reveal I have a guardian angel in the form of an old doll. On one hand, I've always believed that most dolls are at least a bit haunted, and Silent Hill f's unremarkable combat might be too disheartening without a doll to propel its story to its supernatural conclusion.

But these dolls also give me the big, more exciting feeling that there's a piece of me outside myself. She's watching me carefully from the stairwell, hoping I choose wisely.

Silent Hill f revives the horror series' 26-year-old debate: can combat be so bad it's good?

Ashley is a Senior Writer at GamesRadar+. She's been a staff writer at Kotaku and Inverse, too, and she's written freelance pieces about horror and women in games for sites like Rolling Stone, Vulture, IGN, and Polygon. When she's not covering gaming news, she's usually working on expanding her doll collection while watching Saw movies one through 11.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.