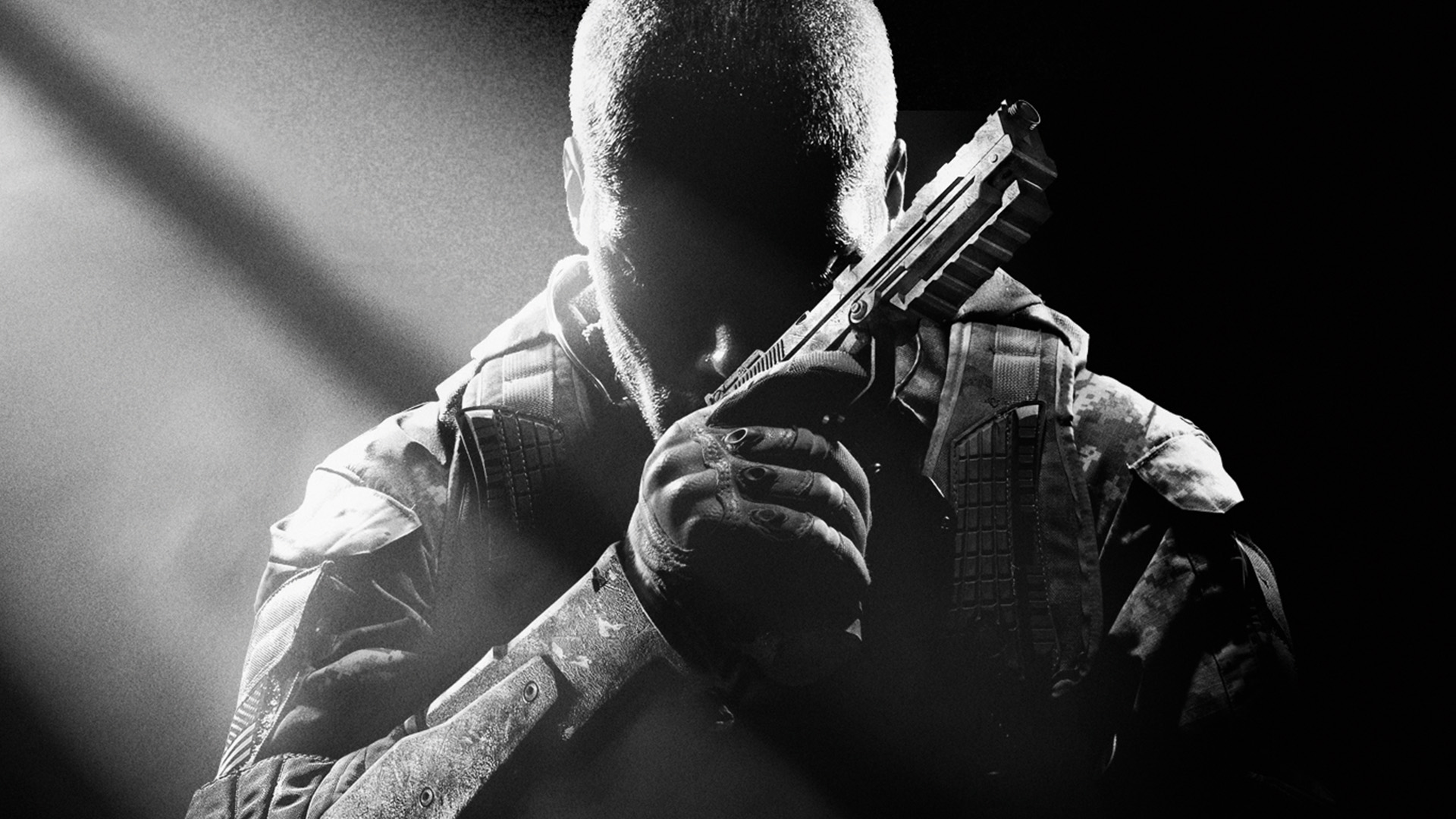

Black Ops 2, Treyarch's unexpectedly experimental shooter, still surprises and discomforts – though not always intentionally

Feature | Revisiting Call of Duty: Black Ops 2, the FPS that turned the sub-series into a vital pillar for Activision's shooter behemoth

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

For a first-person shooter, there's no greater honour than a musical theme from Trent Reznor. It's only ever been bestowed on two games: Id Software's Quake, and Treyarch's Black Ops II. Both were studios at the peak of their pop cultural powers, commanding the kind of crossover appeal that publishers dream of but rarely achieve. In 2012, a new Call Of Duty campaign was still a catalyst for water-cooler conversation, including one in Reznor's studio. "I think I have played them all," he told USA Today at the time, "with the exception of one or two that may have come out when I was on long touring jaunts."

The theme Reznor composed for Black Ops II is a muted, bass-led mood piece. It growls more than it barks, and when it finally bites – with teeth, to use the language of Nine Inch Nails – it comes as a shock. "There is a lot of reservation and angst and sense of loss and regret and anger bubbling under the surface," said Reznor. "So it didn't make sense to have a gung-ho, patriotic-feeling kind of theme song. It has to feel weighty."

In that explanation, and over five-and-a-half minutes of industrial unease, Reznor captures the character that distinguishes Black Ops from its peers in the COD canon. This is a sub-series composed from the disjointed memories of traumatised soldiers. In the original Black Ops, Treyarch looked over the CIA's history of foreign intervention and mental programming with a distrustful eye. In the sequel, it catalogues the generations of pain left behind by the people weaponised in those conflicts.

The campaign's primary protagonist is David Mason, son of Alex Mason, the latter of whom starred in many of the most troubling scenes of the original Black Ops. In fact, Mason Sr is an early member of triple-A's distant fathers club, which many have suggested is a symptom of the crunch that takes game developers away from their own families. The Last of Us' Joel would join the following year. "Go back to the army," a young David mutters cattily in an opening cutscene. "Like you did when mom died." In those early hours, Black Ops II regularly returns to the failed states where Alex Mason made his mark, for better or worse. The man is the Forrest Gump of morally dubious US missions: name a coup or invasion, and he was there, taping somebody to a chair.

Biggest op

Unlike the Modern Warfare games, however, Black Ops II isn't interested in telling a global story. Though it hops between continents and nominally concerns a new cold war, the game specialises in manhunts – much like the real-life JSOC organisation that Mason Jr grows up to join. Whether in Angola, Panama, Afghanistan or Yemen, the local ideologies and power struggles at play are backgrounded in favour of matters personal to the Mason family. In the early Call Of Duty games you at least had a sense of what you were fighting for; in Black Ops II you are simply fighting towards. And the thing you are grasping for is Raul Menendez.

This story is one of a cycle of revenge – one that continues until after the credits roll.

Menendez is the sort of villain who insists that you are the same, you and he – though in fairness to the Nicaraguan arms dealer, he does vary the wording somewhat. "We are the same, David," he purrs. "Shaped by those we have lost." Menendez has lost his sister, Josefina, to Alex Mason's squad during a raid in Nicaragua; David has lost his father in a vengeful and rather convoluted plot by Menendez. Like an Aeschylus tragedy yelled over the sound of machine gun fire, this story is one of a cycle of revenge – one that continues until after the credits roll.

These personal motivations fold neatly into the working lives of black operatives, and reflect the dark CIA history Treyarch taps into: Americans fighting wars that aren't their own for ulterior motives. In theory, they should help glue together the plot too, focusing your attention on the characters, rather than the factions and time periods the protagonists pass through.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In truth, though, Treyarch turned in a deeply confusing campaign – one in which a simple story is told in the most complicated possible fashion. Not only is game director Dave Anthony fond of non-chronology, but he laces dialogue with the acronyms and codenames that are part and parcel of COD's military fetish. Batman screenwriter David S Goyer gets a credit, but after handling The Dark Knight's many moving parts with deft coherence, the juggling act falls apart here. It says much that during Black Ops II's final mission, a general we've never seen or heard from before pops up in the corner of the screen to remind us what the state of the world was and who the major players were.

Worse, Treyarch fumbles when handling the personal stories it so desperately wants to tell. In one level that finds Menendez freed by none other than Manuel Noriega – for no Black Ops game is complete without a cameo from a real-life dictator – you control the villain as he single-handedly cuts through an army to reunite with his sister. "Rarrrgh," he screams, more than once. "Josefina!". It's an awkward sequence to play, as the game upends the usual rules of hit points and movement, turning Menendez into a speeding tank in a bid to reflect his protective bloodlust.

At points the mission restricts your weapon choice to ensure messy takedowns, and flushes the screen with red filters. At others, a still image of Josefina's childhood face flashes embarrassingly across your vision, frozen in time before her disfigurement in a terrible fire. You have to admire Treyarch for attempting such outsized romanticism in a military shooter, but it's a heavy-handed portrayal of trauma, to say the least.

Over and over, Black Ops II establishes Treyarch as both the trashiest and most experimental COD studio on Activision's roster. This was the game that dared to interweave its main missions with a hybrid RTS mode called Strike Force, in which you could zoom out to bird's-eye view with a button, and select to play as another soldier, turret or vehicle instead – taking Modern Warfare's perspective-swapping shtick to its most extreme conclusion. Strike Force didn't work very well, since it was predictably tricky to command the battle as you participated in it, and didn't return for future entries, but we can't fault the daring on show.

Ditto the branching story, much of which might be news even to those who have played the campaign through. Black Ops II's choices fluctuate between the hokily overt – handing you a gun to choose who lives and dies, not once, but three times – and subtle to a fault. One variation to the plot hinges on whether you pick up a particular file found in Menendez's compound in 1986. Another depends on your catching up to a kidnapped scientist during a rescue mission, and with no explicit timer, you're left with little indication that you've tilted the game's ending in dramatic fashion. In the context of a series that often plays like an interactive theme park ride, it's genuinely shocking to learn that your success or failure in a mission wasn't predetermined.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine 353. For more in-depth features and interviews diving deep into the gaming industry delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

The rescue mission marks a high point in the campaign, as Mason Jr and friends visit a floating island resort named Colossus. Effectively a super-yacht scaled up to the size of a city, Colossus is a hideaway for the one per cent, and the sole place where Treyarch's vision of 2025 convinces. The spectacle is breathtaking, and the mission's brutality is juxtaposed playfully with calming hotel muzak. It feels as if a studio with the dial stuck to ten might finally have learned dynamics from Reznor. The mastery collapses minutes later, however, in a nightclub shootout. As terrorists open fire on civilians, Treyarch moves the shooting into slow-mo and pumps up the Skrillex. In an age when club shootings have become a part of our horrible reality, playing the scene for style feels tone-deaf in the extreme.

For the most part, the future setting is an excuse for Treyarch to let loose with its gadgets. In 2025, no door is simply unlocked, but willed open by a wrist pad with the design sensibility of an N-Gage. Often you'll be looking down on your protagonist as they tap away at a brightly coloured screen, through an implied AR display that itself fills your peripheral vision with illuminated lines and indicators. Black Ops II is missing the grounding minimalism that guides the very best science fiction.

Still: you can't say Treyarch doesn't know itself. Its second cold war begins when China bans the export of rare earth elements – effectively cutting off America from its drones, and presumably also the computers and televisions that the studio loves so dearly. Every Call Of Duty developer has to find a global catastrophe that personally keeps it up at night, and Treyarch invented its own worst nightmare. By the end of the game you're in the developer's LA backyard, explicitly preventing the death of capitalism.

Whether that nightmare is one shared by its audience is another matter. Menendez leads a popular movement against the super-rich and is, as far as the world knows, a peaceful activist. The idea that a figure like that might also be a narco-terrorist on the side – well, it's a paranoid right-wing fever dream. It's small wonder, then, that after the game's release, Anthony was snapped up by a Washington think tank dedicated to imagining non-traditional threats to America. Treyarch's nightmares turned out to be those of the US establishment.

Aim down sights for our best Call of Duty games ranking!

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.