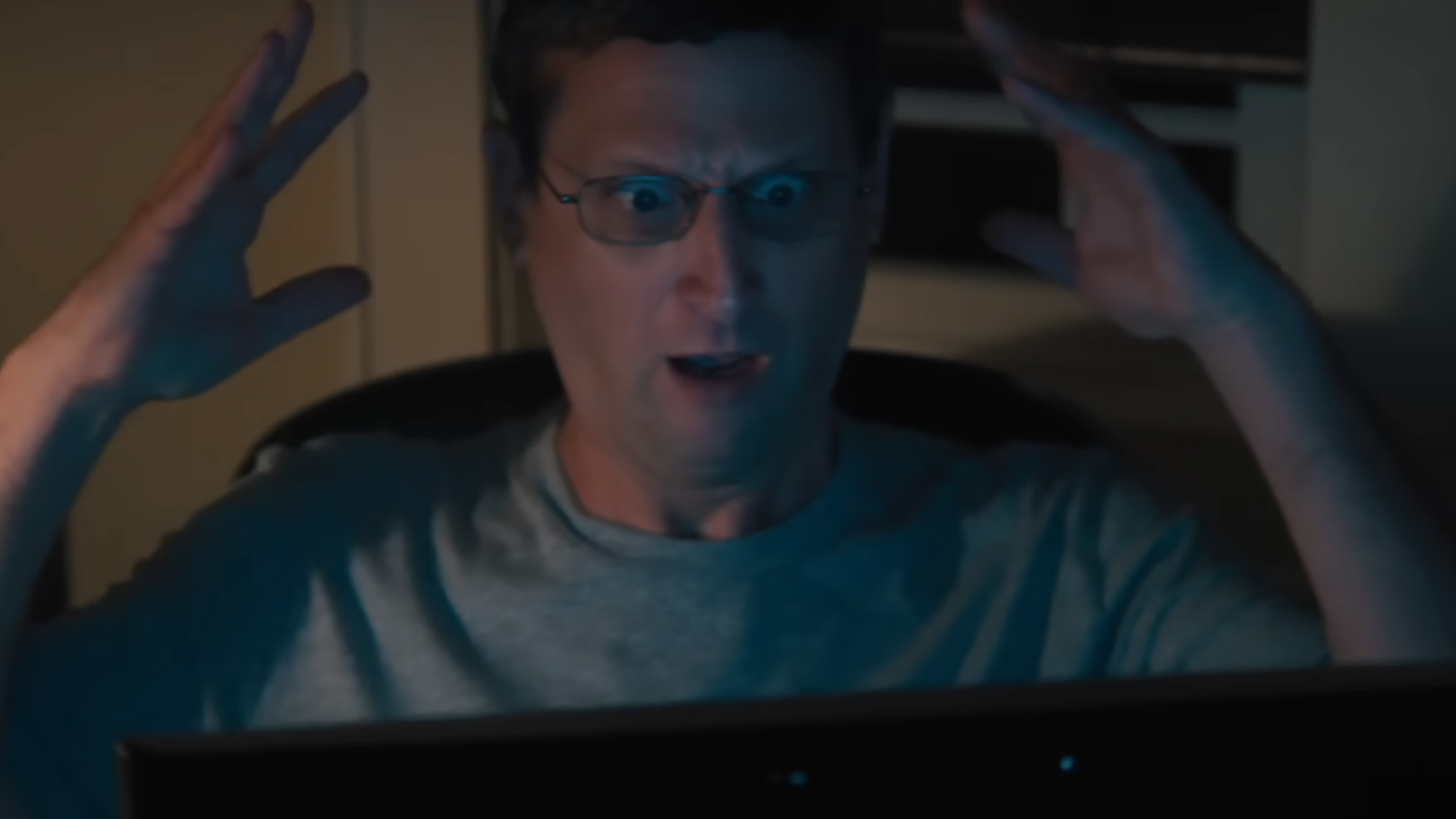

Tim Robinson's darkly madcap comedy thriller The Chair Company is the perfect antidote to the most overused trope on TV

NOW WATCHING | Tim Robinson's The Chair Company is holding up an absurd and awkward mirror to one of TV's most tiring trends

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

I have a confession to make. I'm getting a little burned out on so-called 'prestige television.' If I have to watch another 8 episode limited series about a dejected cop (or gangster) with a troubled past trying to wrestle control from chaos while wallowing in his own guilty conscience, I'm going to immediately fall asleep for 100 years.

Thankfully, while a century-long nap might actually help a little bit, there's a balm for the increasingly tired concept of the TV strongman - Tim Robinson's bizarrely tense and hilariously absurd HBO series The Chair Company.

Centering on a satirical send-up of the ever-present TV strongman archetype, The Chair Company feels like a pointed antidote to the egotistic nature of its thriller genre thanks to a healthy dose of self-aware humor and social cringe that highlight the increasing abandon of its ultimately milquetoast lead.

It's something along the lines of The Man Who Knew Too Little, with co-creator and star Tim Robinson holding up his own oddball mirror to a society that seems bound and determined to trade the concept of a social contract for the right to pursue a personal vendetta.

It's maybe the last word I personally need on the strongman genre, and a perfect counterpoint to the endless stream of po-faced, guilt-ridden trauma cops that will likely never stop patrolling our TV screens.

The ghost of Tony Soprano

The trend of prestige shows that lionize the concept of a lone wolf going outside the law to accomplish bad but necessary things with unilateral force goes back to the early days of the idea of TV shows that elevate themselves above typical network dramas.

In many ways, Tony Soprano is the prototypical strongman archetype of a man whose values (twisted as they are) are constantly tested as he moves deeper into his own nonsense, while justifying the results of his actions as necessary evils

The concept seemed to reach its apex with the one-two punch of Breaking Bad and its spin-off Better Call Saul – masterpieces in the narrative of a seemingly well-meaning man falling into an increasingly amoral vortex of desperation and unforeseen consequences. It's hard to top Walter White and Saul Goodman as disturbed men driven to incalculable social destruction.

But that doesn't seem to stop anyone from trying. In the last few months, I've seen at least 5 limited series about cops who are so haunted by their dead children and past mistakes that they go off the rails making whatever compromises they believe are necessary to their self-validating ends.

The trope also lives in some of the most successful prestige dramas of the present TV landscape, such as the ever-dominant Yellowstone, a show about a salt-of-the-earth land baron patriarch and his family resisting the encroachment of the outside world into their idyllic territory. It's yet another angle on the concept, and in this case, one that showcases the inherent messaging of the strongman archetype – that it is necessary to use any means, even illegal and amoral ones, to accomplish a personal ideal.

The TV strongman deconstructed

Some of the ongoing crop of strongman-centric dramas have had their charms – Netflix's Wayward gets by on inverting some of the genre's gender dynamics and on the strength of the performances of the show's creator, Mae Martin, and the always captivating Toni Collette, for example.

Still, it's Robinson and his co-creator Zach Kanin's The Chair Company that truly beats the horse to death in a well-deserved mercy killing with its madcap lead Ron Trosper (played by Robinson himself), a corporate executive and family man who becomes obsessed with unraveling the Gordian knot of a furniture sales company with inscrutable secrets at the expense of his personal commitments.

It all starts with the most unlikely of circumstances - Ron's chair collapses during an important company presentation, embarrassing him in front of his peers. Determined to make a complaint about the dangers of the faulty chair, he begins to dive ever deeper into a surprisingly creepy rabbit hole of abandoned warehouses, mercenary short-order cooks, and hoarder houses. Meanwhile, the chair company itself is nested in a seemingly endless web of shell companies, fake websites, and other odd twists.

It's easy to see how Robinson's Ron Trosper fits the basic ideas of the TV strongman: an ego-driven personal goal, an increasing distance between his family and his peers, and a willingness to bend his own morals and even the law to achieve satisfaction.

Nonetheless, there's a typically satirical edge to Robinson's performance in The Chair Company with enough social weirdness and absurdly lyrical characters to compare the show to Robinson's previous TV triumphs, Detroiters and I Think You Should Leave, and his recent film turn in the Paul Rudd co-starring Friendship.

An oddball underdog

What makes The Chair Company such an effective deconstruction of the concept is the overall unnecessary nature of Ron's personal conflict, coupled with the surprisingly unhinged circumstances that occur as a result of Ron's obsession with figuring out exactly whose fault it is that he was made to look slightly foolish in front of his bosses and subordinates.

In some ways, a journey like Walter White's makes sense – his desperation at life-altering circumstances drives him to build an ever-expanding criminal empire that forces him to adapt to the violence of the moment. But for Ron Trosper, the stakes are nothing, and there is no impactful tragedy driving his Quixotic quest for answers about defective office chairs.

By removing the actual stakes of such a story while ramping up the madness at the heart of its all-too-sincere lead character, The Chair Company manages to illustrate just how futile the excesses of the TV strongman genre can be.

Ultimately, the only real risk is that Ron Trosper will go from temporarily embarrassed to permanently off-the-rails, a fitting parable for a TV landscape that often feels dominated by self-serious anti-heroes whose only relatable quality is carrying the same thousand-yard stare I get when I see a cop flashing back to fishing with his dead son.

In a way, that's what makes a character like Ron Trosper more relatable, and also makes The Chair Company far more relevant than a show that invents windmills for its protagonists to tilt at rather than letting their unstable lead characters build their own hallucinated giants to slay.

The hero we deserve

That feeling of petty personal drive is something most people have experienced in one way or another – an interior notion that demands addressing in an outward way, no matter how trivial.

What sets most of us apart from Ron Trosper, however, is Ron's elevation of that kind of personal peccadillo into ego-fueled vigilante determinism, an inability to turn away from the gulf of self-aggrandizing obsession.

For someone like Ron Trosper, that need to feel important in a nihilist world is all-consuming, an endless fall into a privately-tailored hellhole of anti-Streisand Effect obscurity, a retreat from community exacerbated by every attempt to exert a level of control.

Given the state of the real world, The Chair Company is a timely reminder to examine the idea of morally questionable individual quests for relevance at the expense of self-growth, and to ask ourselves if those are truly the heroes we need right now.

The Chair Company is currently airing on HBO in the US and Sky/NOW in the UK. When you're all caught up on The Chair Company, check out our picks for the 25 best shows on HBO Max to watch right now.

I've been Newsarama's resident Marvel Comics expert and general comic book historian since 2011. I've also been the on-site reporter at most major comic conventions such as Comic-Con International: San Diego, New York Comic Con, and C2E2. Outside of comic journalism, I am the artist of many weird pictures, and the guitarist of many heavy riffs. (They/Them)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.