Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond brings the Western Front to Oculus Rift, where "anything you pick up can be used as a weapon"

Respawn details the improvisational flair that virtual reality brings to Medal of Honor

I shot VR Nazis in Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond and I liked it

We’ve been here before – in the back of a landing craft, rocked violently by artillery shells, rammed foot-to-foot with frightened fellow soldiers. This time, though, as we look down to jam a clip into our Thompson, we notice a new detail – a hand shaking uncontrollably. The first ever FPS series to make us feel vulnerable is back. And in VR it looks more terrifying than ever.

Medal of Honor was invented for kids. There aren’t many first-person shooter franchises you can say that about - and it’s not necessarily the origin story you’d expect for a series which has, at times, been harrowing in its depiction of the struggle against the Nazis. But that’s what Steven Spielberg intended when he brought Medal of Honor to his very own game studio, DreamWorks Interactive.

“He came back from shooting Private Ryan, and was like, ‘I just made this R-rated movie. It’s very violent and bloody, kids aren’t going to be able to see it,’” recalls Respawn’s Peter Hirschmann. “He remembered a time when popular culture was filled with stories of World War 2. There were shows on TV. There were many more veterans from the war. He lamented that kids were growing up not learning these stories. And he knew that the entertainment platform of the future was not movies, it was games.”

Spielberg gave DreamWorks just a few weeks to develop an initial prototype. The studio cobbled together a demo using the engine it had built for The Lost World: Jurassic Park, constructing a makeshift chateau and underground V2 base. “We built some humanoids,” Hirschmann says. “They didn’t even shoot back, but you could shoot them and they would react. It proved out that shooting Nazis was fun.”

If you wanted to reach kids in the late ‘90s, you made games for the PlayStation. But that was a problem for DreamWorks: until then, first-person shooters had been the sole preserve of PC developers. In order to put out Medal of Honor, the team had to grapple with the brand new Dual Analog Controller.

Steering with the stick may be second-nature today, but there was no precedent when Hirschmann and his colleagues first figured it out. “Spielberg doesn’t get enough credit for helping shape the FPS world that we live in today,” Hirschmann says. “He was the father of console FPS.”

Change of command

“Spielberg doesn’t get enough credit for helping shape the FPS world that we live in today.”

Peter Hirschmann

Medal of Honor went on to achieve greatness in Allied Assault, lighting the flare for Call of Duty to follow. Then most of the early talent moved on – Hirschmann to LucasArts, Vince Zampella and the Allied Assault team to Infinity Ward – and Medal of Honor struggled to reassert itself alongside Call of Duty.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Today, though, Hirschmann is back at the head of a Medal of Honor team, under the auspices of Zampella’s Respawn Entertainment. And he’s back in the fertile field of hardware experimentation that produced Medal of Honor’s first success. It’s not analog sticks he’s wrestling with anymore, of course, but another unconquered technology: VR.

“When we got together with Oculus for the first time, I remember saying, ‘Alright, where’s the big binder of best practices for VR?’ And there isn’t one,” Hirschmann says. “Nobody knows anything. It was such a scary and liberating thing.”

In the three years since then, VR has become a little less of a hinterland - Half-Life: Alyx in particular was a landmark moment for the medium. But it’s worth remembering that developers have come to their own solutions independently. As in the ‘90s, the Medal of Honor team has worked out a new system of control from scratch.

Almost any gun in Above and Beyond can be fired one-handed, but bring up a second hand and it locks in, granting you a new axis of rotation and a stability buff under the hood. “Throwing a grenade is a physical act,” Hirschmann says. “It becomes a very skill-based activity.”

That shaking hand in the landing craft, which features in Above and Beyond’s Gamescom trailer, is indicative of the tactile relationship players now have with their weapons. Those fumbling, faltering moments where you stuff more bullets into your gun - and the enemy, knowing you’re vulnerable, push their advantage - only heighten the emotional connection Medal of Honor originally excelled at. “You know you’re wearing a headset,” Hirschmann says. “But your brain can’t help but process it as if it were real at an emotional level.”

Life on the line

There’s an aspect of Medal of Honor that often gets forgotten in the aftermath of Call of Duty. Yes, the original games established a tone of reverence and mourning for the wartime experience of Allied soldiers, rooted in Saving Private Ryan and the recollections of Spielberg’s veteran consultants.

But Medal of Honor’s influences go back further, to the behind-enemy-lines and POW dramas of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Hirschmann tells me there was an unused music track for the original game titled ‘Colditz Castle’. Above and Beyond taps into that pulpy history of escape attempts and derring-do, casting you as an OSS agent and bringing back the disguise mechanics of the ‘90s games. “A lot of the gameplay is about sneaking, sabotage or stealing something,” Hirschmann says. “We have a really fun mission built around search and rescue.”

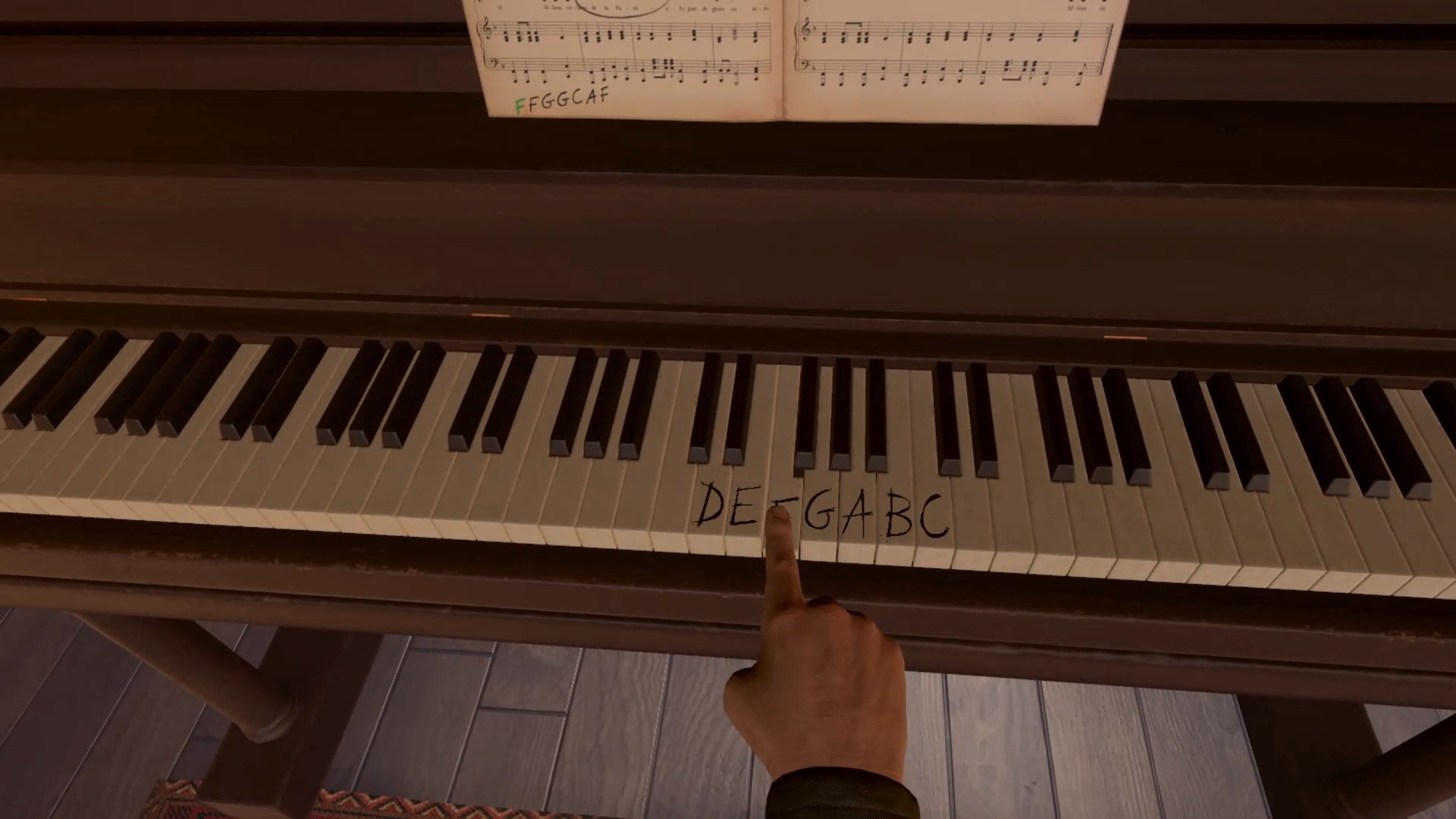

In fact, VR has introduced elements of stealth and simulation to Medal of Honor for the first time. Peek around a corner with your whole head and a Nazi is likely to spot you - but use just one eye and you might just get away with it. Similarly, Oculus’ touch controllers allow you to weaponise props in a way past Medal of Honor games never did. In Above and Beyond’s story trailer, a player picks up a bust of Voltaire and smashes it over a Nazi officer’s head - the French philosopher’s “payback”, as Hirschmann describes it.

“Anything you pick up can be used as a weapon,” he says. “Books, pieces of art. There’s a line in the trailer where the sergeant says, ‘We’re going to have to improvise, lieutenant.’ That’s a very meta line, because motion-controlled VR? It’s all improvised.” In short, VR has made Above and Beyond unpredictable. When’s the last time you could say that about a Medal of Honor game?

For more, check out the biggest upcoming games of 2020 and beyond still on the way, or watch below for our latest episode of Dialogue Options.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.