The science of Netflix, and why it always knows exactly what we want to watch

Check out the latest stats and tech powering Netflix’s (successful) quest for world domination

The rise and rise of Netflix is a cultural phenomenon. Having grown from a modest online DVD rental business to one of the largest, most financially valuable companies on the planet, Netflix is one of the most powerful players in the entertainment business. You know you’ve made it when your brand name gets its own slang phrase (Netflix and chill), and enters mainstream language as just another way of saying “I’m watching TV”. Understandably, less progressive aspects of the industry have lashed out at the streaming giant, the recent declaration that Netflix-published movies aren’t eligible to win awards at the rather haughty Cannes Film Festival is the latest in a long line of kickbacks against Netflix’s success. But what does Netflix do that its competitors don’t? What’s the secret sauce that has lead to the company amassing 125 million paying subscriptions all over the world? The answer - in large part - is tech and algorithms. Sexy, sexy algorithms.

Brace yourself for some numbers (but don’t panic or glaze-over - they’re genuinely cool numbers). Did you know that Netflix is available on over 1700 devices worldwide? Speaking to the audience at Netflix’s recent ‘What’s next’ event in Rome, which I attended, Todd Yellin - VP of Product - compared most people’s usage of Netflix to that of a great book, where you’re so hooked you want to read it everywhere until you’ve reached the last page. You read in the living room after work, you read in bed before turning out the light, you pick it up in the morning and take it on the train for your daily commute. And in your lunch break… You get the idea. Given Netflix’s ubiquity across so many platforms - TVs, games consoles, phones, tablets, laptops - we are able to carry it with us wherever we go, whatever we’re doing. What’s more, the experience is largely the same on whatever of the 1700 devices we access it on, and with the ability to download, you don’t even need to stream to access this streaming service.

That kind of portability goes a long way - literally, with the service's growing status as a travel essential fuelling the rise and development of the best VPNs for Netflix - but it’s only half the picture. There are currently 300 million user profiles on Netflix. Which means an average of about 2.7 profiles per account. During his talk Yellin showed us that his account has five profiles - his own, his wife’s, his older daughter, his younger son, and his father. It’s not only a deeply personal phenomenon, but a shared one. In the same way we create WhatsApp groups to communicate with our friends and family, or share a TV within a household, so the modern trend is to have a single (or a couple of) Netflix account for everyone to watch. Being able to economise in this way AND still have a suite of individual content for each user is a massively powerful tool in the modern age, where vast amounts of TV and movies compete for a huge array of tastes and appetites. Netflix quite literally is everything to everyone (well, within reason).

Anywhere, any time, beautiful

Having shared accounts alone isn’t enough, and here’s where the clever bit comes in. From day one, Netflix realised it was dealing with a global audience, and its recent event very much leaned hard on the idea that people from anywhere in the world with watch TV and movies from anywhere else, providing the story is great and it appeals to them in some way. The result is that many of Netflix’s original European shows, which the company is investing $1billion in over the next 12 months, will be available all over the world. This is unprecedented in the history of entertainment, and it potentially opens up the audience for shows that - under traditional broadcast models, or more restricted streaming services - would never break into other countries, no matter how great they are. It’s worth remembering that Netflix is now available in 190 countries all over the world, making it a truly global platform. If you’re the showrunners for the upcoming The Rain, a show created and filmed in the relatively tiny country of Denmark, the opportunity to reach so many people is a no-brainer.

But does exposing a show to such a broad audience really have a noticeable effect on its viewership? Surely (generally speaking) people are often reluctant to try things with foreign-sounding names, or with that scariest of things: subtitles. Netflix doesn’t think that’s the case, and has done its homework on the subject. To give you an example of how confident the company is that its shows will work all over the world, the original House of Cards on Netflix was available in seven languages, back in 2013. Its latest original - Lost in Space - is available in 26 languages, merely five years later. That’s a phenomenal expansion, but one that speaks to the power of making cool stuff available to a global audience.

And Netflix really does see its audience as global. Within the company there’s no talk of shows being created or commissioned to cater for geography. Instead, all Netflix users are broken down into ‘taste communities’, of which there are roughly 2000. Roughly speaking, this is how Netflix’s algorithms determine what to show you, based on the way you browse and view other shows. It isn’t as simple as just putting users into traditional groups, such as ‘hardcore sci-fi viewers’ or ‘people who love documentaries about food’. It’s a blend of genres, sub-genres, and smart suggestions that define what taste group you fall into - the stuff you’re served when you log into Netflix is essentially the wishlist you built (but didn’t know you were building). And your taste community has nothing to do with region, or even a predilection for watching TV from within or without your home nation. Sure, you may be British and watch stacks of classic British comedies like Blackadder and Absolutely Fabulous… but you’ll still end up gravitating towards the same taste group as people anywhere else in the world who also happen to watch episodes of the same shows. It makes sense and seems like such a simple idea, but removing the idea of regionality is a game-changer.

The results are fascinating. Netflix’s first German original show - Dark - aired late last year. It’s a very European take on a time-hopping murder mystery, and airs in its native German language… yet 90% of viewers aren’t from Germany. In fact, 81% of people who saw the show actually watched it with the (overly American-sounding, and really quite awful) English-language dub. Suburra, an Italian crime drama, had a 50:50 split between people who watched in native Italian and those who chose the dubbed version. While this potentially means a larger percentage of the show’s viewers were Italian-speakers, there’s no doubt that the dub - and availability in different regions - increased the show’s reach and audience numbers. In the case of Dark, it’s staggering how far Netflix pushed the show beyond the its native Germany. It’s fantastic TV, and very much got the audience it deserved. New original The Rain actually has its English-language dub performed by the majority of the Danish cast, because they speak such great English and it lends an unparalleled level of authenticity to the show.

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

What’s in a name?

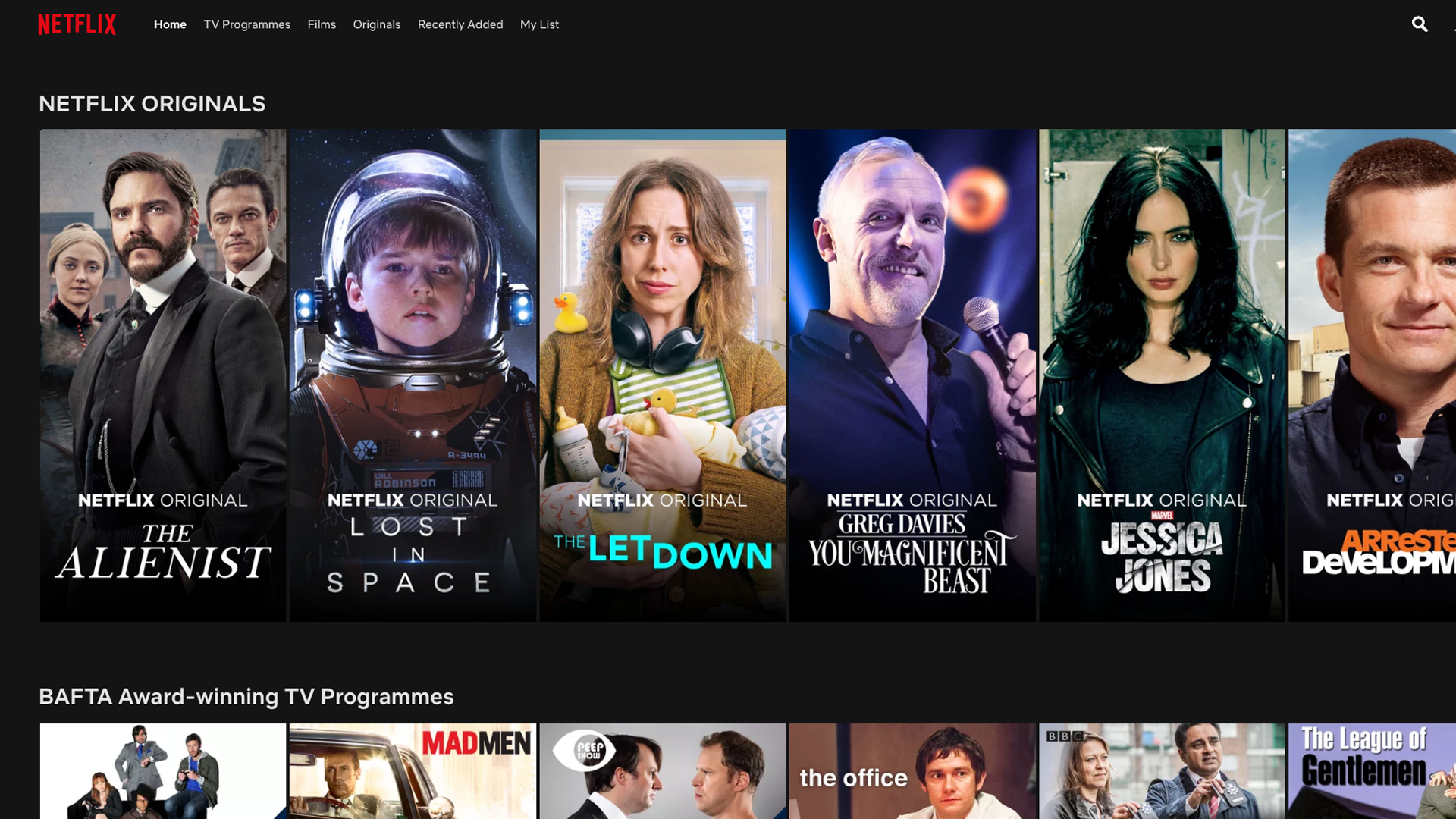

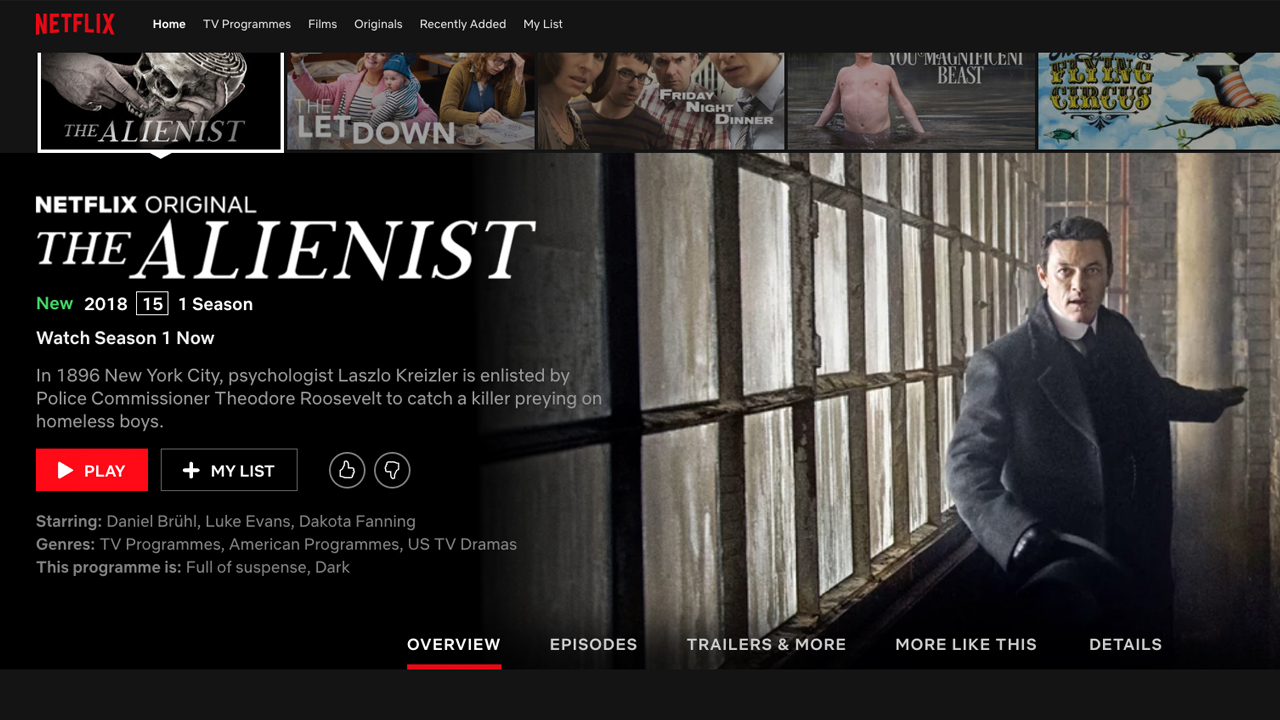

Making a show available, however, doesn’t mean people will simply watch it. On average, we flick through 40-50 show tiles before settling on ‘something new to watch’ when we browse Netflix. And while we’re split into taste communities and served entertainment based on what we will probably like, that isn’t always enough to push us over that ‘just try the first episode’ hurdle. That’s why some programmes have their names changed for different countries. Spanish hit Las Chicas del Cable became, literally, Cable Girls in the US and immediately saw a 22% increase in viewers in that country. The rise was only 19% in the UK however, but still a significant boost in audience. And that’s more people viewing Netflix for longer, renewing subscriptions, and bringing in friends and family for more shows.

Altering the name doesn’t always work, however. Friends from College - a US comedy - showed boosts in ratings when its title was changed for places like Spain and Italy but… it actually dropped 14% when translated into Dutch. So, in the Netherlands, it still appears as Friends from College in the main menu. Without disappearing into a world of stats here, the point is that not only does Netflix think about the shows you might like, it also thinks about how you might like to see them; how best to make you watch. It’s advanced A/B testing, but it’s something Netflix is capable of because its tech and algorithms are so modern. Other studios who rely heavily on posters, trailers, and traditional media simply can’t keep up. It’s actual smart TV, and other networks and platforms can’t compete with that scientific, stat-driven approach. What’s more, because we pay a flat fee for Netflix, it rarely feels intrusive and overly commercialised like Google Ads or Facebook Ads (which are based on our, often unrelated, browsing or social media history), so it’s a more ethically-friendly use of our personal data. Does Netflix use our data in other ways? I’d be shocked if it didn’t, but there’s so far been no public evidence of how this happens.

This personalisation and catering to taste even extends to the images used in the thumbnails. As a bit of fun Yellin brought Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker and showrunner Annabel Jones in on a video call, and asked them to select the thumbnail they thought would be most popular for a show like Black Mirror. Obviously, they were wide of the mark, but Yellin demonstrated how Netflix discovered that most people who watch Black Mirror knew what the show was about, so a simple, bold logo on broken mirror background was by far the most effective choice. He also said that an image featuring a scene from one of the episodes was trialled for bringing new viewers to Black Mirror, so was served into certain taste communities to expand the show’s audience. Again, it makes sense when you think about it, but no other entertainment service is laser-targeting audience in quite the same way and… well, that’s how you reach 125 million subscribers and piss off the organisers of Cannes.

There are still massive question marks around some of Netflix’s strategies. Are they a quality player in movies? Do they spend too much commissioning second-rate TV shows? Is this level of spending and expansion sustainable, and will the bubble burst eventually? While we’ve seen it happen countless times before, there’s no doubt that Netflix is smart enough and agile enough to be a mainstay of our entertainment lives for years to come. And right now, it’s only getting bigger and better - which can only be a good thing for us.

Want more? Here are the best shows on Netflix. And here are the best movies on Netflix.