Mafia 3 might help open-world crime reach its true potential

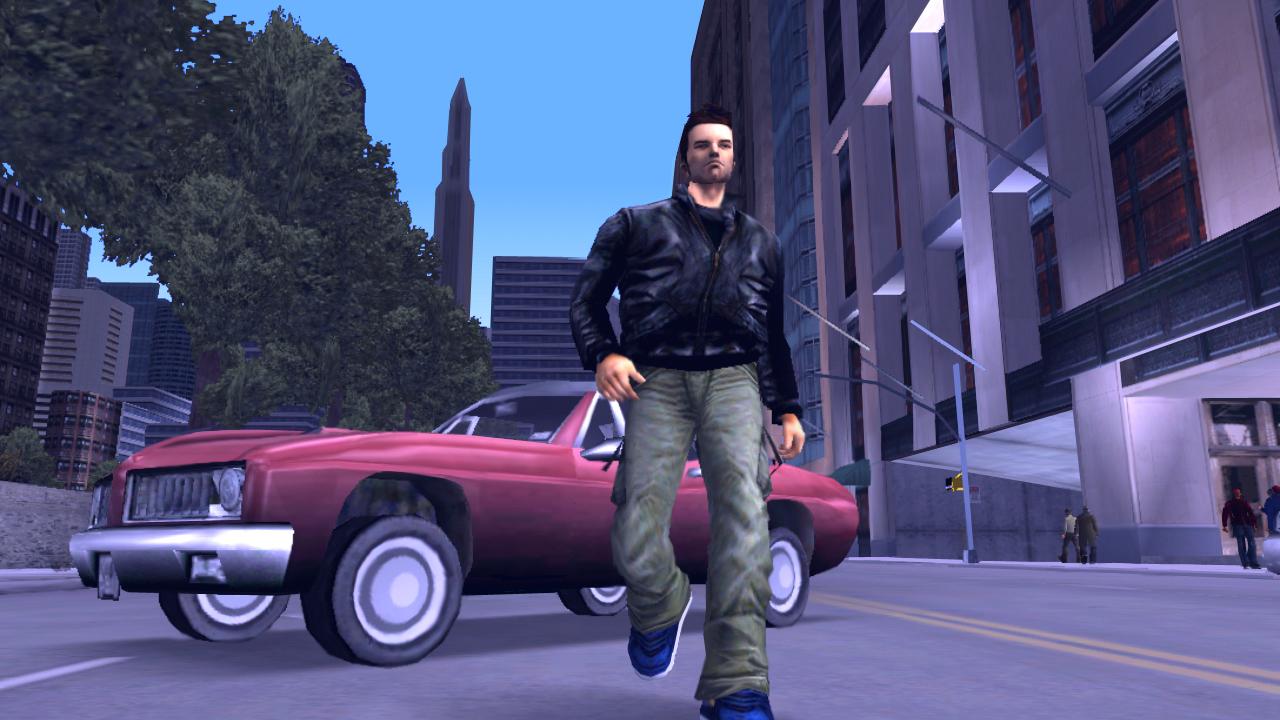

The open-world game, in the modern, popular sense – let’s not get into a debate about the likes of Ultima, Zelda, and Turbo Esprit – has not done a lot growing since the genre’s point of ignition with the release of Grand Theft Auto 3. In fact, in its 15 years on this earth, it hasn’t matured much more than the equivalent human would have.

On the surface, it appears to have evolved quite a lot. We’ve long-since replaced blocky, spartan cityscapes with lustrous, detailed, urban worlds. The basic systems of run, gun and drive have seeded ground that now gives life to all manner of grappling, cape-gliding, skyscraper-jumping extravagance. Mirroring real-life urban sprawl, city maps we thought were huge back in the early ‘00s now fit into a single suburb of an average-sized game, while rural fantasy environs wave around their mighty greenbelts in an ever-escalating pride war for the most impressive girth of flora.

But, RPGs aside, the physical scope of the open-world game hasn’t developed in tandem with any healthy expansion of intent. Because what do we do with our ever evolving suite of abilities? How do we express ourselves in these increasingly detailed, painstaking constructed worlds? We blow shit up, and cause a big funny mess, and then we restart and do it all over again. Because that’s all that most open-world games ever invite us to do.

Grand Theft Auto’s madcap escalation through the PS2 era emphasised that cartoon spectacle was the series’ primary purpose, the juvenile shock value of Rockstar’s narratives providing only a persuasive secondary argument for the case. Not that most people play right through GTA’s story at all these days. Crackdown brought in an addictive collect-‘em-up meta-game that fuelled giddy, superhuman feats. A great spin on the existing open-world ideal, but one whose innovations in turn fuelled only a larger-scale version of the same goon-smashing, car-crashing, virtual action-figure toy box. The same conceit we’d been playing with in video games for six years. The same conceit we’d been playing with on the carpet since we were six years old.

Red Faction: Guerilla? Literally ‘Breaking Stuff: The Game’. Just Cause and Mercenaries? Deliciously intricate interaction systems, but essentially a route to the more complex destruction of a wider variety of things. Saints Row? Pretty much the logical end point of all of the above. In fact the series made sure of it, altering and rebooting its scenario as many times as necessary to ensure that it wrung out every possible way of destroying every possible thing with every possible flavour of silliness. Out of options? Screw it, it’s The Matrix now. Go crazy. The Arkham series was initially more restrained, using its maps as more of a hub-world to contain isolated, linear level designs, but even the world’s greatest detective succumbed to incendiary, vehicular action by the time his trilogy ended.

And frankly, I find it all a bit wasteful. I’m tired of seeing sumptuously crafted, living, breathing worlds, and knowing that they exist only to destroy. All of the games mentioned above are great fun – and my time in GTA 5’s story mode alone runs to an hour count in the triple figures – but I can’t help feeling that open-world structures can be used for more.

The problem, of course, was caused by the success of the format’s early presentation. With Grand Theft Auto arguably the biggest game series in the world since part three, the industry’s quest to emulate its fortunes has been endless. Great games have come about as a result, but ultimately they’ve all aimed in the same direction. And you get the audience you design for, in any creative pursuit. It’s rather telling that GTA4’s attempt to strip things back to a more sober formula was rejected by a great many fans brought into the series by the likes of Vice City and San Andreas. 15 years of emulation has cultivated rather a strong feedback loop of design and taste, and the open-world is being held back as a result.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But for the likes of me, there’s hope on the horizon. That hope takes the shape of Mafia 3. Because, while certainly scaling up the scope for creative violence past that of its predecessor, the fact is that said predecessor is not Grand Theft Auto, but Mafia 2. And Mafia 2 takes a very different approach. A divisive one, but one that I found incredibly refreshing. It uses its open-world city not to encourage wanton carnage, or continually distract with a thousand extraneous activities, but as a means of wrapping its – in truth rather linear – campaign in a vast swathe of ambient, real-world resonance.

Many didn’t like that, wanting more to do in between the game’s smartly designed missions. But as a means to ground an action game with realism and the weighty sense of a wider context, I loved it. Here, we’re talking about a game that lets you actively restrict your cars’ speed to legal limits in order to roleplay a real, professional career criminal, lapping up its consummate vintage atmosphere as you drive, instead of baiting the cops for a fight. It lets you reflect your criminal progress by purchasing sharp suits, not helicopter gunships. Mafia 2 knows what it’s about, and it never loses focus. As one of the few crime games packing a genuinely mature story, Mafia 2 would have lost a lot had it been flooded with mini-games. At the same time, its use of a less functional, but more coherent, atmospheric open-world acts as a fantastic amplifier for that tale.

Mafia 3 is certainly expanding the gameplay options, but having now played over two hours of Hangar 13’s sequel, I’m confident that coherence and maturity are still at the forefront of its design philosophy. Yes, you’ll have many things to do at any given time, but they all tie immediately into the onward thrust of what once again looks like a very nuanced and thoughtful story. Where other open-worlders smear themselves sideways with countless goofy diversions, every one of the (many) angles of attack Mafia 3 provides for any given objective pushes you forward. Everything possible action is focused on the same goal. Your path of personal choice is wider, but you’ll never lose sight of your ultimate direction.

And there are other, rather more unexpected pieces of intelligent, open-world dexterity on show. There’s more than a dash of Hitman or Deus Ex in the way that M3 uses its wide, organic environs to give multiple, strategically diverse routes into its localised objectives, rewarding freeform planning without ever descending into anarchy. There’s also the way that it uses its breadth to facilitate entirely different paths through its more directed, more set-piece driven missions.

Infiltrating a mob penthouse? Feel free to gun your way in through the front door. Or if you’d rather go quiet, you can always drive around the block to find the underground car park. Expanding on Mafia 2’s ethos in more exciting, player-authored ways, Mafia 3 nevertheless maintains a sense of combining the best of closed and open-world design, wrapping a meaty sense of freedom around a skeleton of curated, tonal intent.

That’s what open-world games have been lacking for a long time. They’ve all too often seen the worth of a simulated city as lying exclusively in having the free space to cause chaos. For me, there’s just as much value to be had in the simple sense of playing through an adventure that takes place in a coherent, affecting, believable, wider world. In fact all of this reminds me of a very different open-world template that appeared shortly before Grand Theft Auto 3, and which seemed to understand that implicitly. Shenmue. Shenmue was good, wasn’t it? It seems odd that we’ve diverged so far from its lessons, despite the long-heard cries for its return. But thankfully, it seems that not everyone has forgotten them.