"We want you to feel like it's the game you remember playing, not necessarily the game that you did play": System Shock and Dead Space devs on the art of the remake

Interview | Exploring what goes into an excellent game remake or remaster with the minds behind some of the best

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

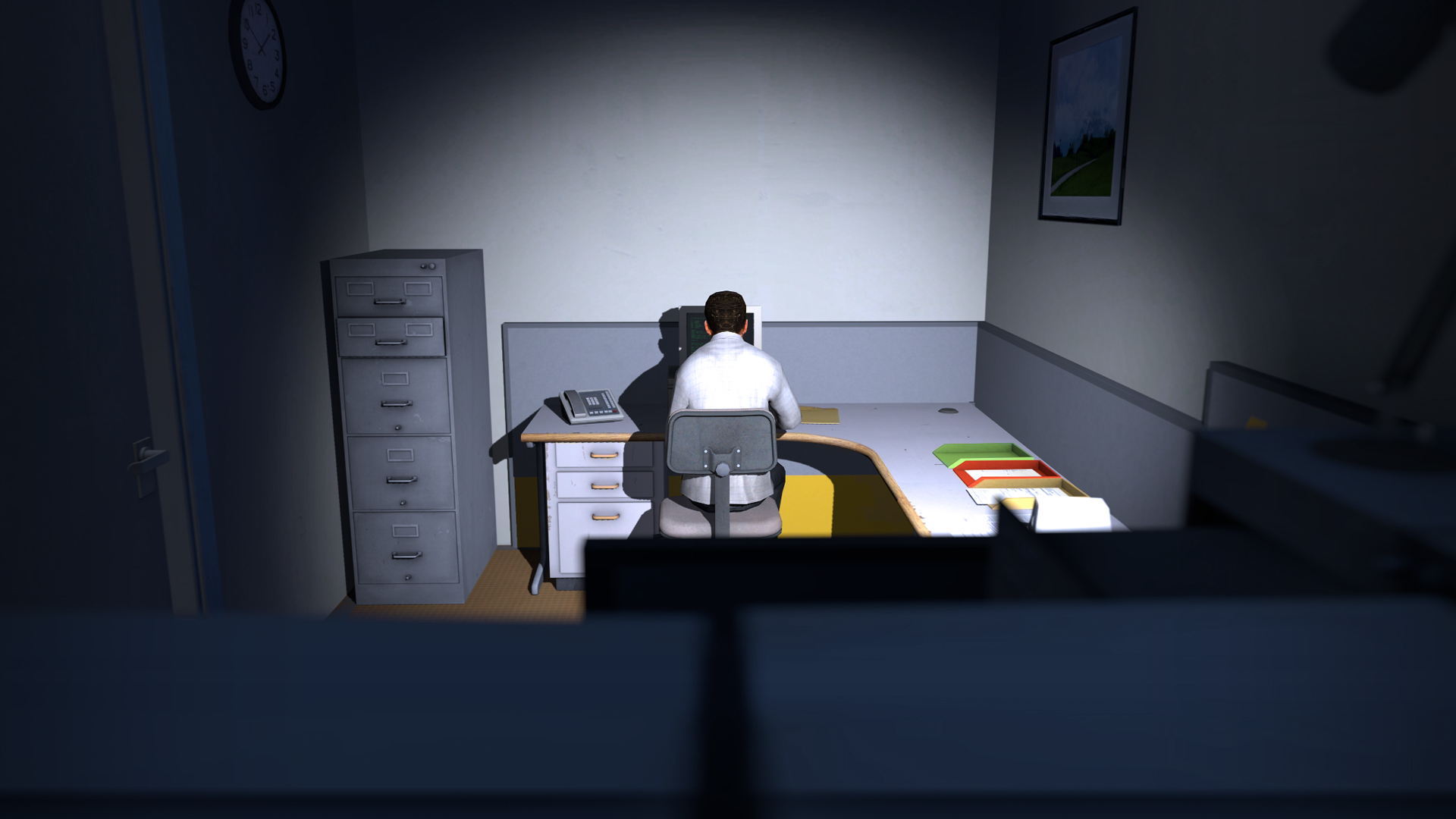

William Pugh, director of The Stanley Parable: Ultra Deluxe, has a bone to pick with us. Chatting about the game, we mention that certain publications, Edge included, gave a slightly lower score to 2022's revamp than the 2013 original, despite all of its additions. "If the original was nine out of ten, and we have completely faithfully preserved that, how can it be docked points for four years of work?" he laughs. At face value, it's a reasonable question. But this also illustrates that the world of remakes and remasters often obeys a strange logic.

That it took four years to create Ultra Deluxe is further evidence. Initially, the plan was for Pugh and Davey Wreden (the creators of the original) simply to port The Stanley Parable to PS4, but since it was made using Valve's Source Engine, that became a problem.

"We tried getting support from Valve to get the Source Engine version running on PlayStation, and that was a non-starter," Pugh explains. "So it needed an engine transplant." Once that was under way, discussions began about new content, in the form of platform-specific endings for the PS4 and other console versions. A trickle of ideas became a flood, and a six-month project began to grow.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #415. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

It's a story that Stephen Kick, head of Nightdive Studios, should be able to relate to. Starting 12 years ago with the rerelease of System Shock, Kick's aim was to rescue games from obscurity so that people – not least himself – could play them again.

In time, plans for a more radical treatment of System Shock emerged, and a Kickstarter to fund the remake was successful, but "for better or worse," Kick says, what had been mooted as a fairly faithful rebuild in Unity mutated as the money facilitated grander ambitions.

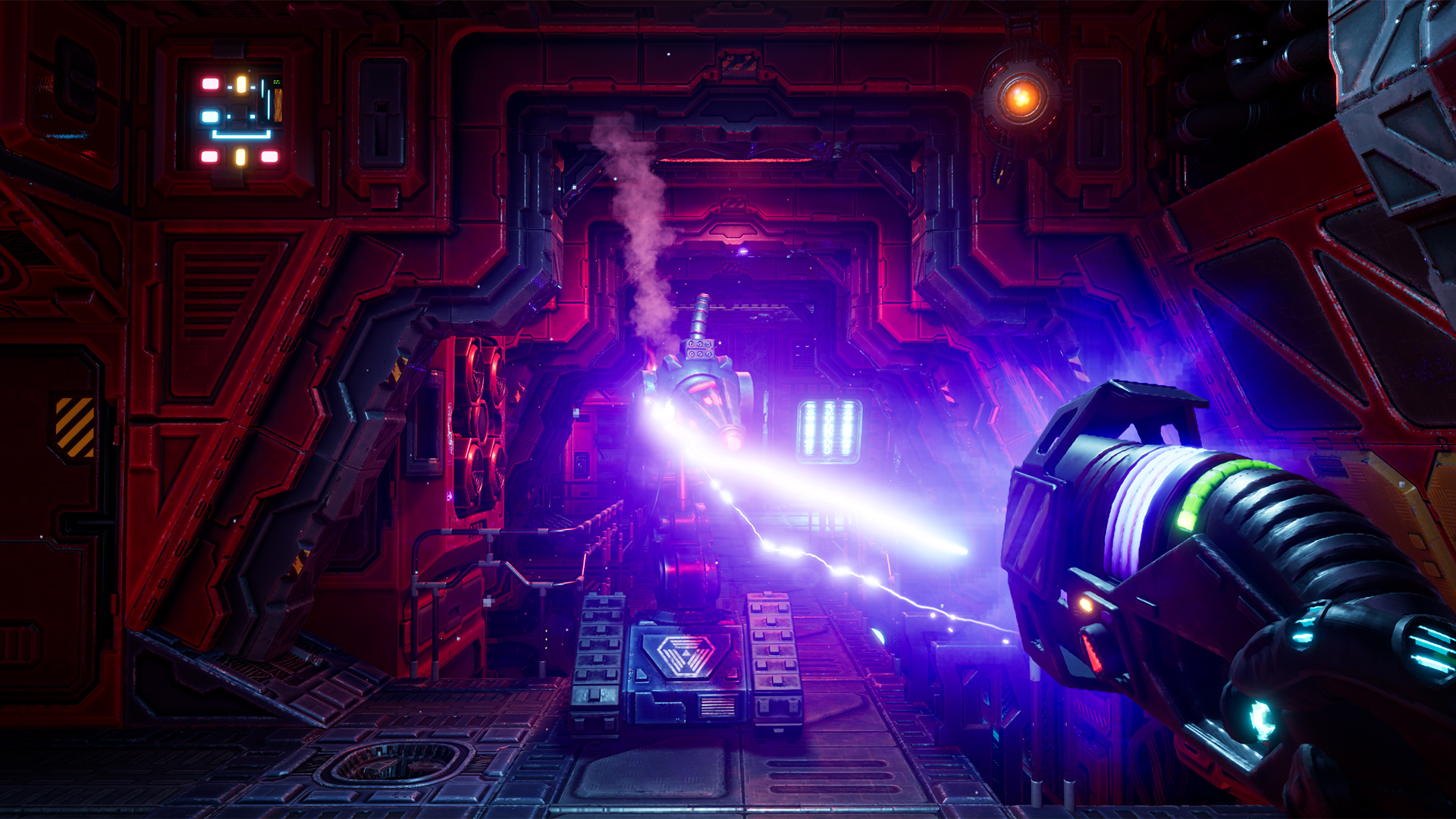

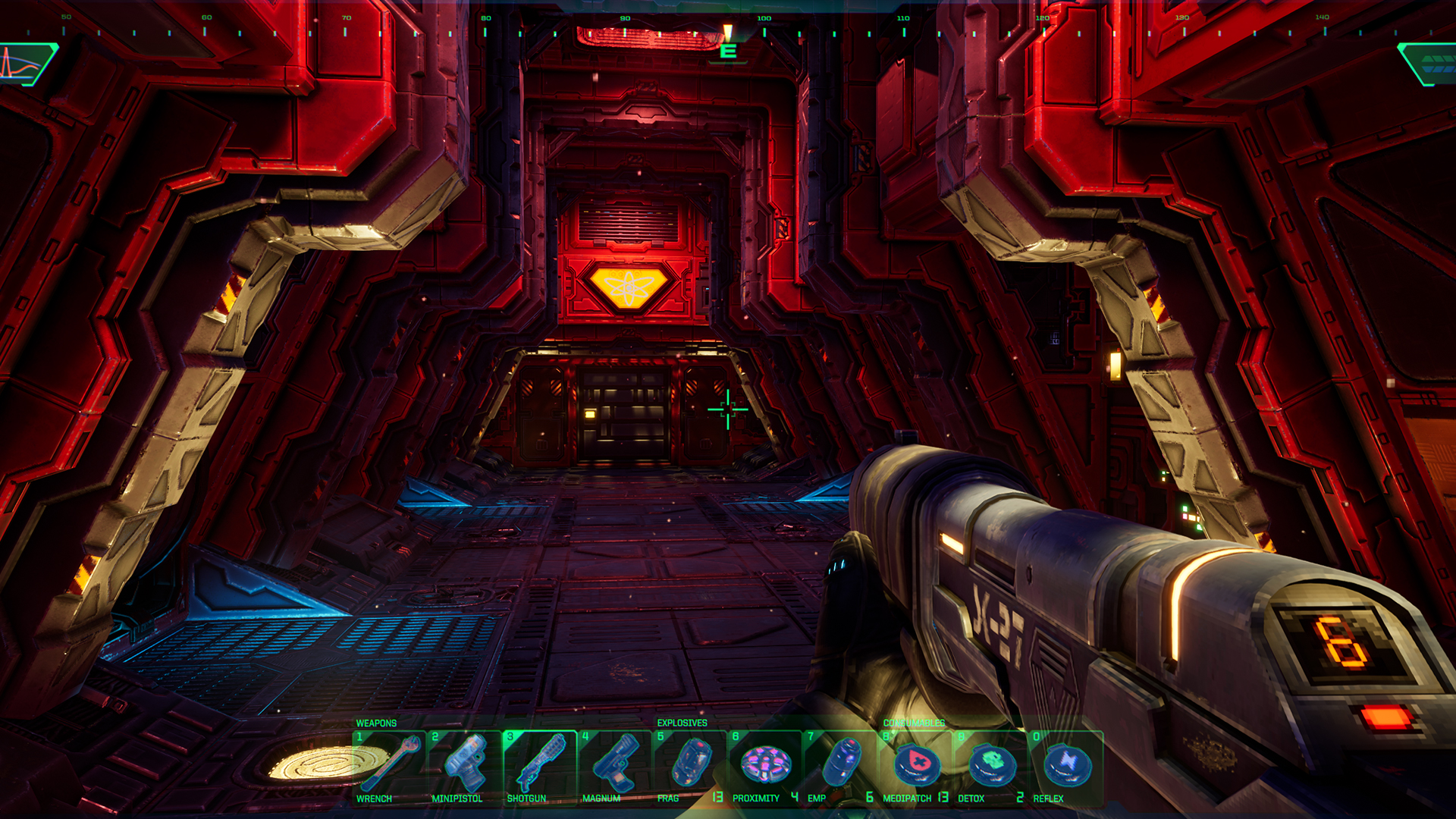

Ultimately, "it abandoned a lot of what made System Shock special," Kick says. "It started looking more like a standard sci-fi game." That version was scrapped for the final version, built in Unreal Engine but with more modest alterations.

A titan, reforged

We shouldn't be going in and saying we're going to do it better

Philippe Ducharme

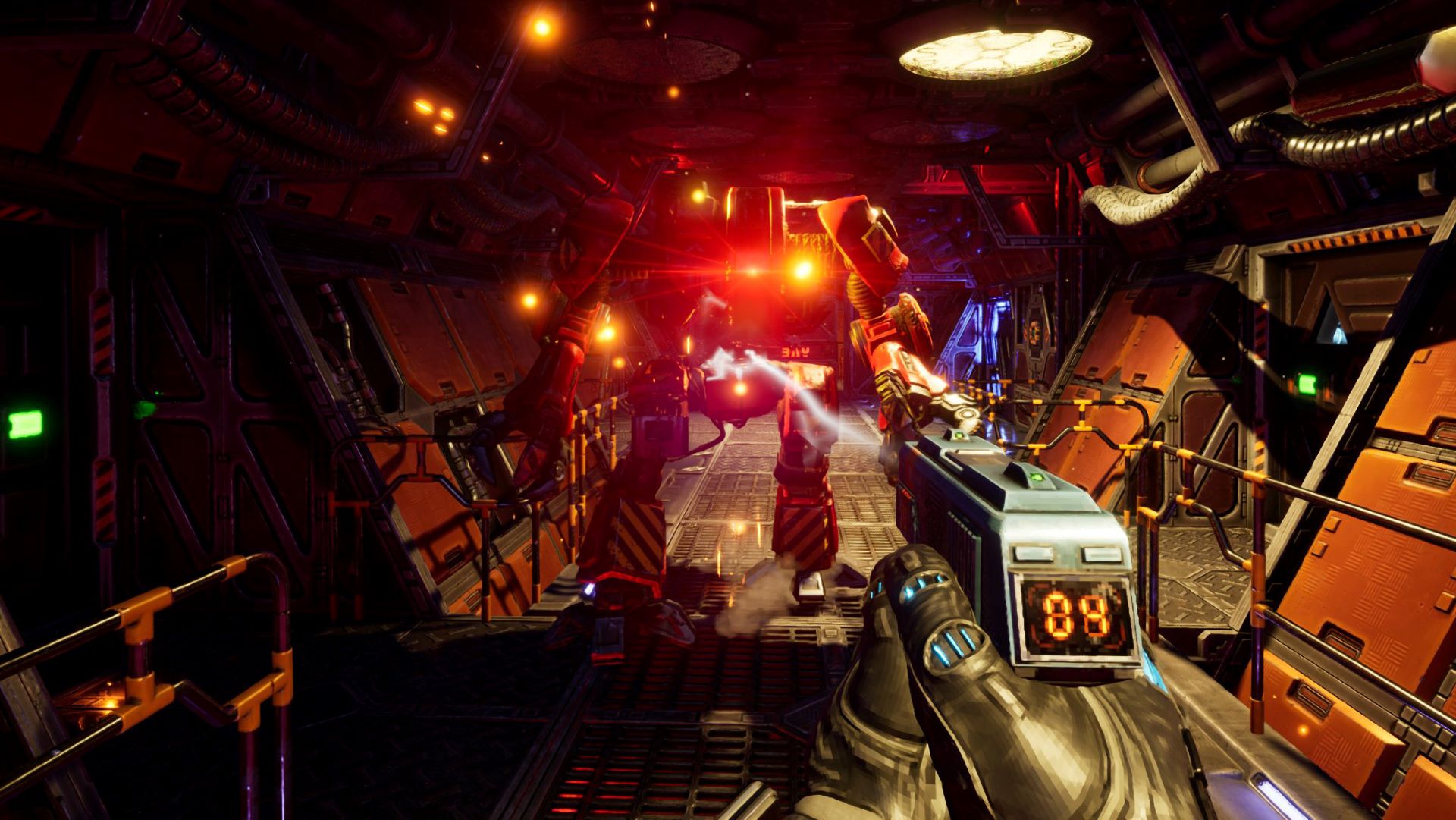

Not all remakes and remasters go through such tribulations. For EA's Motive Studio, for example, the process of recreating Dead Space was a smoother ride.

Some of the staff had even worked on the series before, and when discussion began to circulate around EA about reviving the IP, Motive's leadership was keen to step in. Executive producer Philippe Ducharme was one of those who jumped at the chance. "The first discussions were: 'Are we making a remaster? Are we making a remake?'" he says. "And what's the difference between remakes and remasters?" That the original's engine was 13 years old by that point pushed the team towards rebuilding from scratch.

Still, all such projects face the same difficult questions: what should and shouldn't be changed? What does it mean to be 'faithful' to the original? Motive set out some clear goals here. The first was to honor the legacy of the 2008 game, Ducharme says.

"The reason we're making a remake is because it was a fantastic game, so we shouldn't be going in and saying we're going to do it better." That notion then had to be balanced against a need to meet modern expectations, while the team had to stay focused on making impactful alterations and not allow ambition to take over.

Motive's senior creative director, Roman Campos-Oriola, followed similar rules when it came to the creative vision, not least: "If there's no reason to change something, don't change it." And what is changed should accentuate the qualities of the original.

For example, your journey around the Ishimura would now be seamless – with no loading times or transitions between chapters – so as not to pull you from an otherwise immersive experience. The tactical flexibility in combat, based on dismembering enemies, was also deepened. "Instead of creating new weapons, the philosophy was to include more weapon abilities inside the gameplay loop or make them work better with each other," Campos-Oriola says.

Decisions of this kind are never easy, a point confirmed by Nightdive producer Justin Khan, who worked on the System Shock remake.

"With every mechanic and every design element," he says, "there would be big debates within the team." The decision to add an option to aim down sights, say, now standard in FPS games, took some two months of discussion. Since then, the remake team has tried to be more mathematical about it, Khan continues.

"We've kept a rule of 15–30 per cent change. Whether it's narrative or art or mechanics, we're like, 'OK, we're allowed to make it 15 per cent different from the original." Of course, not everything can be governed by percentages, he admits, but even when it doesn't quite make sense, it helps keep the design on track.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

We've kept a rule of 15–30 per cent change

Justin Khan

With Ultra Deluxe, meanwhile, the focus wasn't on changing what was there so much as adding to it, in particular the new endings.

"We transferred it into this new engine, and we had Kevan Brighting [the voice of the narrator] on call," Pugh says, "[so] we could add anything we wanted." About 75 per cent of the plan was in place after six months, but in building out new endings and reworking or ditching some, "we maybe went backwards a bit," Pugh says, "and got back down to 60 per cent."

Crucially, though, the core concept was always there. The bucket of reassurance, an item you can carry around to alter various endings, was factored in from an early stage, and the design rules remained from the original: ideas should never repeat themselves, and should always be interactive.

One issue for Pugh was how much to reveal about what they were doing. The Stanley Parable thrives on the unexpected, on triggering consequences and reactions from the narrator by refusing his directions, the range of which is for you to figure out.

"Our creative and marketing calculus was that there needs to be a significant amount of new content," Pugh says, "but we need to market it as having significantly less than that, so it's a process of like, 'Oh, wow, there's more than I expected'."

As they geared up for the game's launch, Pugh and Wreden did start to let on a bit more, so as not to undersell their efforts. But this highlights a perennial conundrum for the developer remaking or remastering: how do you reproduce the original game's element of surprise when people know what they're getting?

Fighting familiarity

It's not just that we should do it because we can do it

Philippe Ducharme

Few remakers have taken this question as seriously as those behind Dead Space, who built a system known as the 'intensity detector' that reacted to the player to alter enemy placements as well as the ambient sounds and lighting, ostensibly to overcome the problem of familiarity in horror games.

It meant, in essence, that Motive could have its cake and eat it – scripting scenes in a familiar way the first time you entered them, then leaving you at the mercy of the intensity detector on repeat visits. "It allowed us to maintain some well-known jump scares," Campos-Oriola says. "But then, if you die or come back in New Game Plus, maybe it's not going to play like that."

And here's another challenge when creating remakes and remasters: how do you decide when to 'fix' perceived deficiencies in the original game, and when to respect design that may feel unwieldy by today's standards?

The answer isn't always as obvious as it may seem. In 2008's Dead Space, there were doors that would be stuck loading for several seconds, and while it was easy for Motive to remedy that, what if that wait actually enhanced the game's tension? "We were careful about these things," Ducharme says. "If we want the tension, then we keep those timings. It's not just that we should do it because we can do it."

The game's zero-gravity sections were one of the bigger fixes in the remake, with new controls that allowed players to move freely in the vacuum, not just boost between platforms. It was an improvement, Campos-Oriola says, and met the aim of deepening the game's mechanics.

"But in [2008's] Dead Space, the fact that it was disorienting was a good thing," he adds. To keep that sense of disorientation in play, more debris and hazards were added to the environments of the new version, so you would have to turn and twist to get around.

Still, not everything is so complicated, especially in remasters. Frequent complaints about games are now well documented online, Kick says, providing a good indication of where to begin.

"We go and we gather up that information before we start a project," he says. "What are the sticking points of this game? What did the original journalists call out as negatives in their reviews?" For instance, in Nightdive's remaster of Turok: Dinosaur Hunter, it felt essential to address gripes with the platforming, which meant adding a touch more height and momentum to jumps. "It became really fun, as opposed to very frustrating," Kick says.

Often, problems in older games stem from the technical limitations of their time – an engine simply not doing a feature justice, for example. "In a lot of cases, when we've heard from the original designers," Kick says, "they'll email us and be like, 'Oh, thank god that you fixed this thing finally'."

It helps, too, that Nightdive has plenty of remasters under its belt now, making its staff highly familiar with older engines such as Quake and Build. "When we get assigned a game that runs on one of these, our guys already have a checklist of stuff," Kick says. "From there, it's just about fine-tuning and tweaking things until they look or feel right again."

In other cases, necessity dictates new features. When Nightdive remastered System Shock 2 for its 25th Anniversary Edition, the console versions required controller support, which never previously existed. That meant creating shortcuts for powers and weapons, switching out a menu system that was probably due an overhaul anyway. But whatever your thoughts about the old system, it had to be done.

"[These are] pretty safe choices and pretty good choices most of the time," Khan says. Besides, the studio often recruits staff from the modding community, well versed in the games they work on, with a keen understanding of what should change.

Picking battles

We want you to feel like it's the game you remember playing, not necessarily the game that you did play

Stephen Kick

Surely the clearest mandate for any remake or remaster, however, is a graphical update. But even here, just how updated should the visuals be?

That aborted version of the System Shock remake might act as a cautionary tale. "I think we always have to be careful that we're not straying too far away," Khan says. "It's hard to quantify, but over the development cycle of the version of System Shock that we did ship, the team got better and better at nailing it first time."

A crucial metric was that you should be able to place a screenshot of the game among shots from 30 other games and immediately recognise it, and to support that a slightly strange guideline was put in place. "One of the principles of this art style was that everything had to look delicious and edible," Kick says. "Like, if I see this in the world, I want to take a bite out of it. It's got this texture and sheen to it that just looks delicious."

As for remasters, care must be taken when stripping out lower-tech solutions. In the famously foggy Turok, for example, it was no trouble to clear the mist, but that triggered unforeseen issues. "As soon as we did that, we noticed that the tops of the trees weren't there," Kick recalls. "They didn't bother putting any of the polys in there." If that wasn't enough, the challenge was significantly reduced when the dinosaurs were visible from distance, so the game had to be adapted to compensate. In the end, an option was given to enable the fog again.

A more general rule of thumb is that "we want you to feel like it's the game you remember playing, not necessarily the game that you did play," Kick says. "The one behind the rose-tinted glasses that ran at 60fps on your N64." It's a sentiment that Campos-Oriola echoes almost exactly when talking about Dead Space, and it's fascinating what people actually do remember.

For instance, Dead Space is seen as a very dark game, and Motive really wanted to play with that in the remake, using more dynamic lighting. An early art benchmark shown to the community, though, received an unexpected reaction. "They were like: 'It's too bright'," Campos-Oriola says. "Then we looked at the original and that corridor was much brighter than what we made."

Bringing the Dead back to life

One advantage was that Motive had access to original concept art, containing details that didn't make it into the 2008 game, so the team could better understand the intention behind the locations.

They also looked again at the films that inspired Dead Space – Alien, Event Horizon – and how atmosphere was created in them. "When you look at these movies, the way they use fog and smoke is really key," Campos-Oriola says, "but that was mostly not present in the original game." The most likely reason is that it wasn't possible then, otherwise it may have been included, so for Campos-Oriola it was again a question of being true to the source by making changes. "Does it still look like Dead Space, even though it's not the same?"

There was still a danger of going too far, however, as experiments with the lighting revealed. The original Dead Space had baked-in lighting, so when the realtime lighting was switched off, it was never pitch black. Now, if all the lights were off and the player was forced to use their torch to navigate, they could still barely see a thing, which seemed less immersive. The solution was to be more strategic. "Maybe not all the lights go off here," Campos-Oriola says, "or maybe there's a window or whatever."

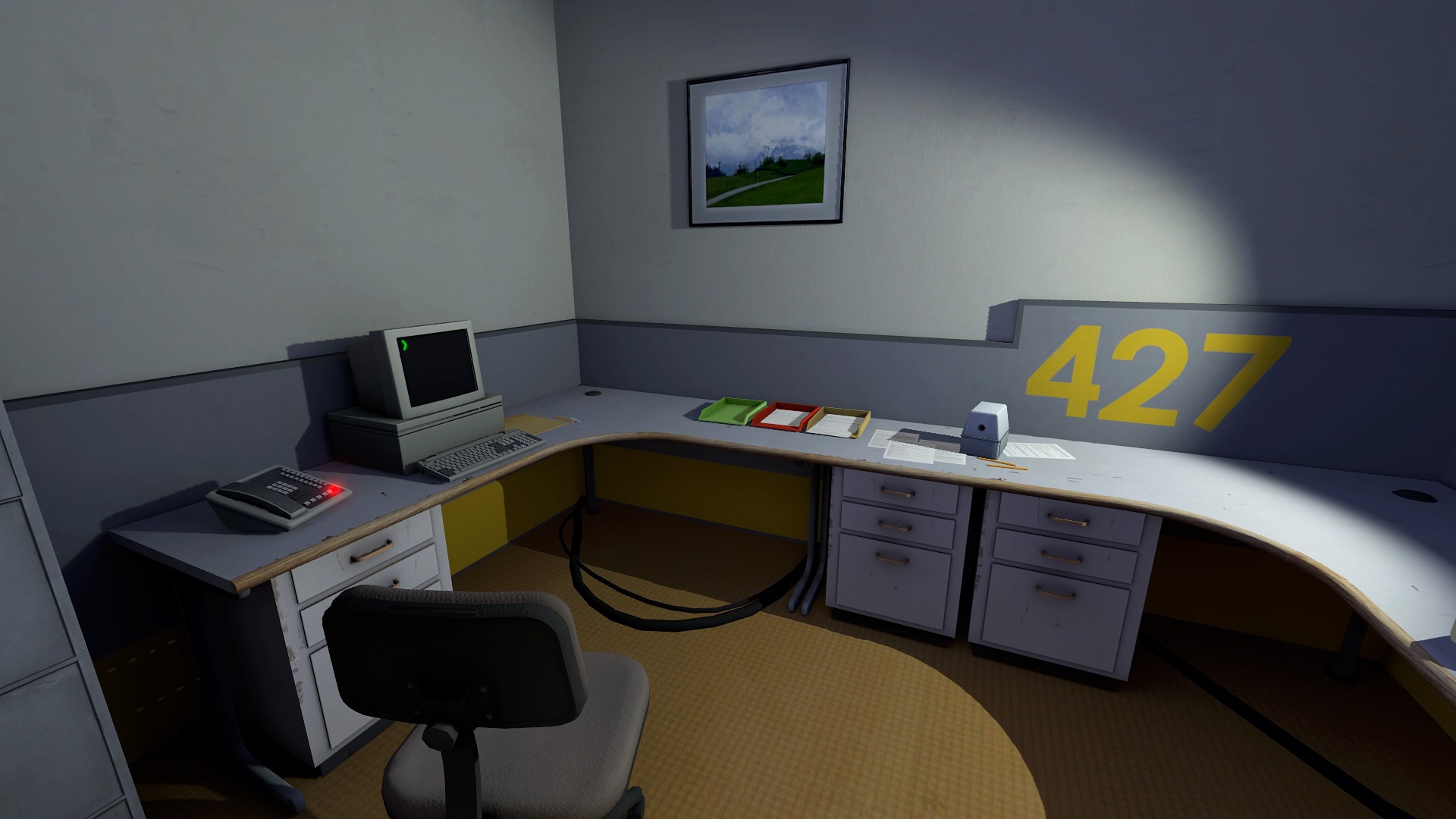

By coincidence, lighting was a sticky wicket for Pugh as well, and while graphical improvement wasn't a major concern for Ultra Deluxe, a new lighting system was unavoidable. "The auto-importer from the Source engine files would give you this horrible geometry that would not light-map correctly at all," Pugh explains. "A real big struggle and point of friction was getting the game to not look shit." Overall, though, Pugh felt it important to retain the Source Engine identity of the game, keeping its "creepy backroom aesthetic", but "just a little bit nicer".

The original was largely a mashup of retextured and tweaked props from Valve games such as Portal, Counter-Strike and Left 4 Dead. When creating new areas for Ultra Deluxe, then, the team adopted "the same approach," Pugh says, "but with [Unity] Asset Store assets and asset packs of, like, 'new futuristic office'. Sticking to a cohesive art direction is the way to go."

Ulta-ultra deluxe

The biggest overhaul for Pugh, of course, wasn't visual but narrative, or rather meta-narrative, since The Stanley Parable was always about how videogames are structured and how agency works within them.

Since the original game, remakes and remasters had become common and lucrative, and user reviews had changed the way audiences interacted with developers. Both developments would feed smartly into the game's additional plotlines, although, for Pugh, that wasn't the core intent.

"The creative process starts from an emotional point of view, rather than a point of like, 'Oh, we're going to comment on this, or try to subvert that'," he says. The inclusion of reviews in the game was a way to put some external judgement upon the narrator, which wasn't there before. It even led the narrator to comment that the original had received such good reviews that the remake was meddling with perfection – a prescient prelude to those slightly reduced review scores, perhaps.

Indeed, the inescapable truth of the remake or remaster is that it enters a world where the original and its legacy already exist, but at a different moment, when gaming itself has changed. And if self-awareness is a central feature of The Stanley Parable, any rerelease has to reckon with it at some level. Remakes and remasters are in conversation with players and themselves by nature. For Nightdive, it was hard to resist referencing some of System Shock's quirks. "We addressed the very labyrinthine design behind some of the levels," Khan recalls. "We wrote a log that didn't exist in the original game [saying], 'The TriOptimum Corporation has intentionally made these corridors all windy and twisty. It feels like they're doing psychology tests on us'. People picked up on that."

Still, you can only play with your source material so much. We wonder if Nightdive ever considered changing the game's iconic 451 door code. "It would be blasphemy," Khan says. Kick concurs: "We might as well not even ship the game."

Join us as we go through the best of 2025, from games to TV and comics, to crown the year's unmissable titles

Jon Bailes is a freelance games critic, author and social theorist. After completing a PhD in European Studies, he first wrote about games in his book Ideology and the Virtual City, and has since gone on to write features, reviews, and analysis for Edge, Washington Post, Wired, The Guardian, and many other publications. His gaming tastes were forged by old arcade games such as R-Type and classic JRPGs like Phantasy Star. These days he’s especially interested in games that tell stories in interesting ways, from Dark Souls to Celeste, or anything that offers something a little different.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.