"We are buying into your vision": Blue Prince publisher Raw Fury reflects on 10 years of indie game magic

Interview | Celebrating a decade of Raw Fury's raw talent

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

When Raw Fury was founded in Stockholm a decade ago, it was as an "un-publisher". It would "treat people like people", would be "for happiness over profit", and would respect videogames as "art", granting them the same status as other, more established media.

This particular approach, it said, would tip the balance more in favour of developers, allowing them to "find success, be happy, and stay independent". It has broken some old rules along the way – not least when it revealed the specifics of its publishing deals publicly, for anyone to scrutinise – while releasing a succession of hits including the Kingdom series, Sable, Norco, Cassette Beasts and, most recently, the sublime Blue Prince. As the company arrives at its tenth anniversary, we meet with its leaders to ask if Raw Fury has delivered on its big promises.

Diamond in the rough

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #411. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

On April 21, 2015, Jónas Antonsson and two fellow Paradox alums – Gordon Van Dyke and David Martinez – revealed Raw Fury. In the announcement, they called it "a new breed of publisher for boutique and indie games". More than that, they said they were in the business of "un-publishing – in the sense of trying to dismantle how publishing traditionally works, in favour of actually being there for the developers".

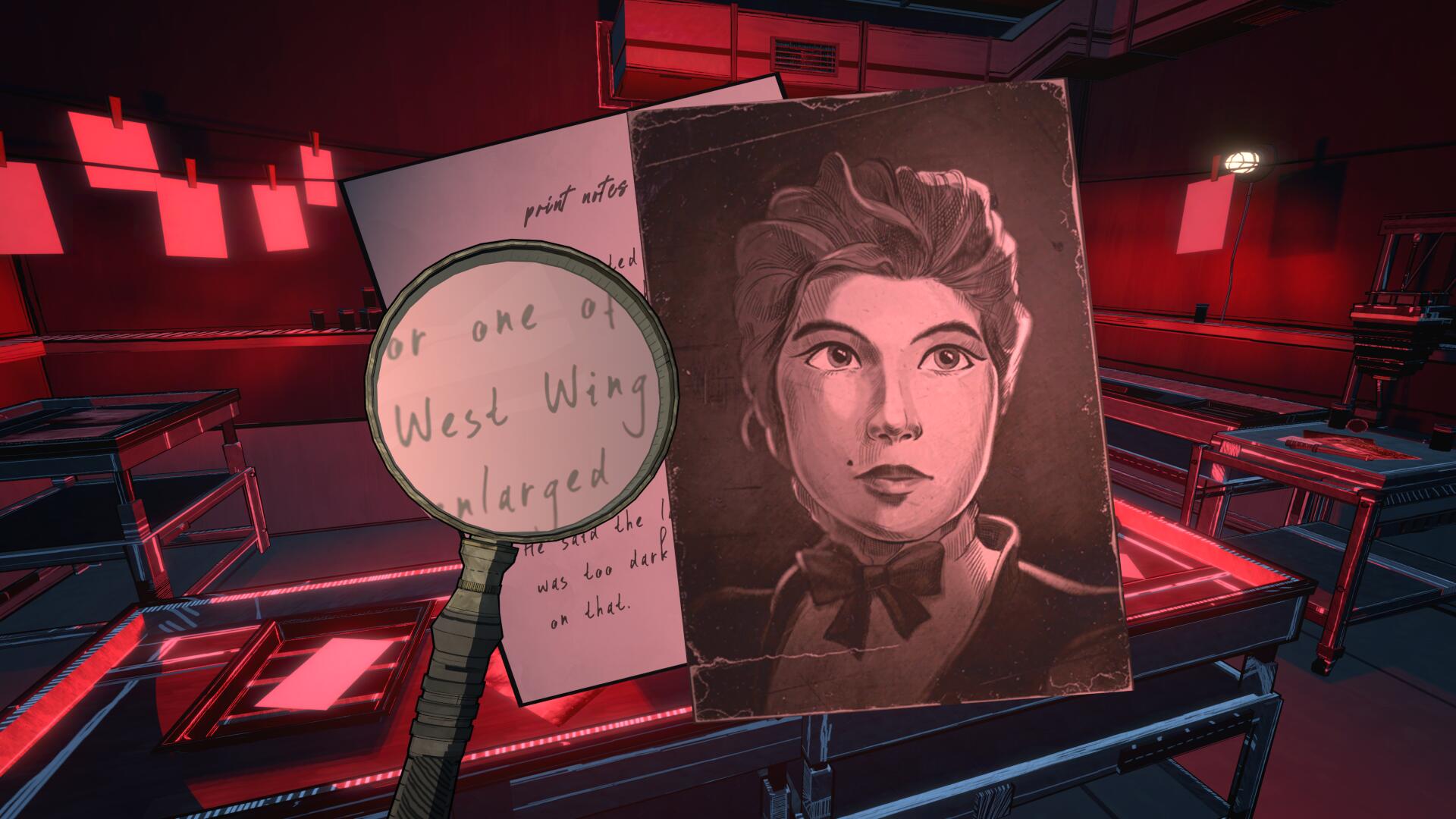

In the decade since, they've published an eclectic portfolio of games, jumping between genres and styles. Their first game, Kingdom, was a sidescrolling minimalist RTS in which you play as a monarch expanding their settlement and fighting off nightly raids by squat ghouls in masks. Their second title was '90s-style point-and-click mystery Kathy Rain, filled with clever puzzles and a twist-laden plot.

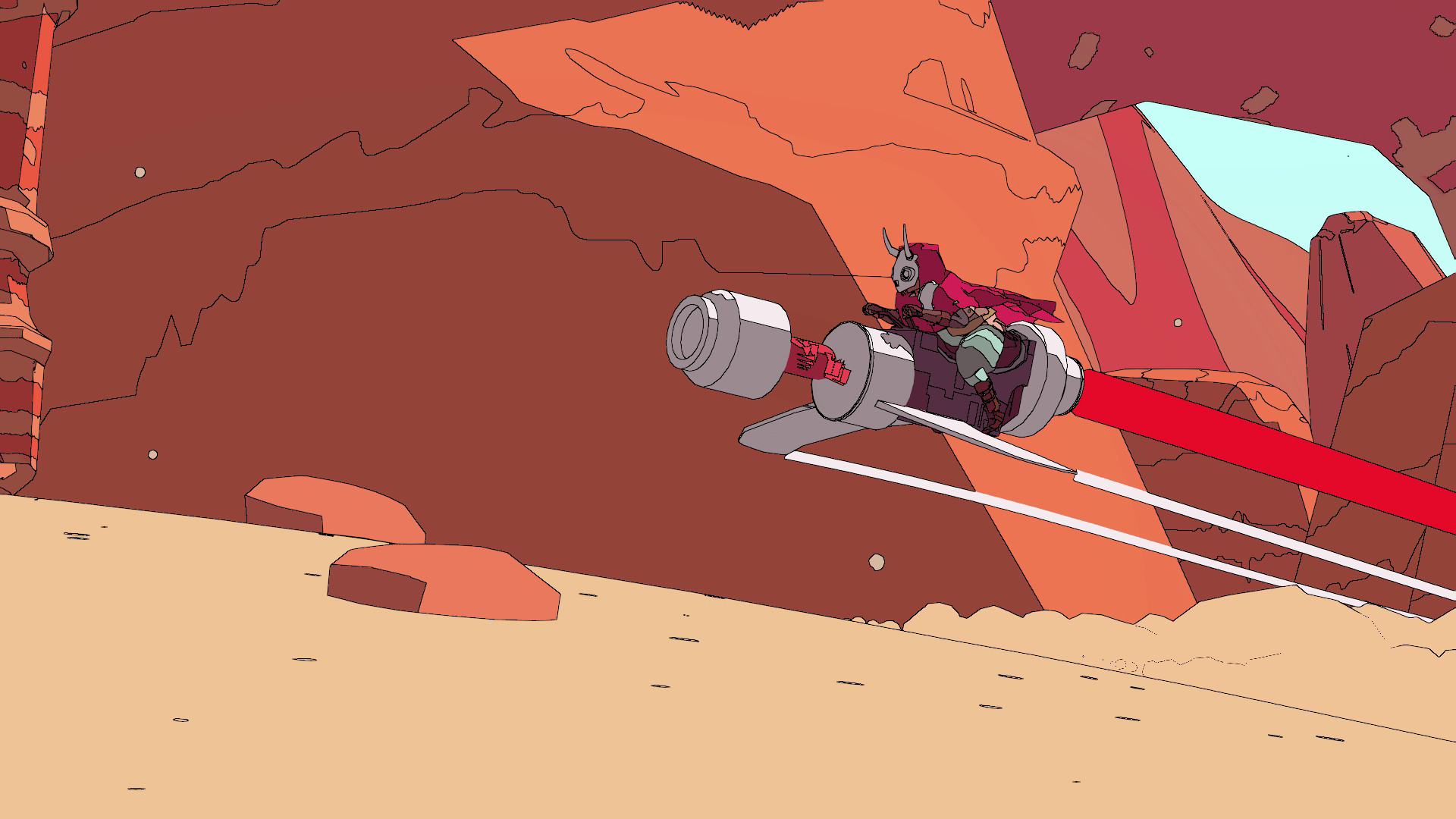

Also finding a home in the catalogue is open-world sci-fi explorer Sable, citybuilding toybox Townscaper, the Pokémon-like Cassette Beasts, and an adventure game set in the surreal world of Tove Jansson's Moomin stories. But a varied portfolio does not a dismantling of traditional videogame publishing make.

The founders of Raw Fury believe two things set the company apart from other publishers: its relationship with developers, and the contracts it makes them sign.

"There had been a lot of innovation in games, and this is an industry where the pace is frantic," Antonsson says of the years leading up to Raw Fury's founding. The early 2010s were marked by the transition from physical to digital and the proliferation of game engines that suited smaller development teams. Unity and GameMaker were on the rise, and Epic changed to a subscription model that favoured small developers, giving them access to the full version of Unreal Engine for less than $20 per month.

Meanwhile, Steam Greenlight and Steam Direct created a viable path for developers to self-publish on PC gaming's most prominent storefront, and Kickstarter found its momentum in 2012, with Double Fine becoming the first videogame developer to raise over $1m, opening the doors to a crowd of veteran studios that did the same. In their wake came smaller, younger teams raising funds for their first commercial projects.

I knew the magic that was there,

Jónas Antonsson

To some, all this opportunity for indies looked like the death of the traditional game-publishing model. Antonsson certainly saw problems on the horizon. As the founder of casual-game studio Gogogic and later in the role as Paradox's vice president of mobile, he had seen the promise and challenges of mobile gaming firsthand.

"There had been a blue ocean, and in just a few years things were red and scary with sharks," he says now. Discoverability would become the number one issue for all these small developers vying for attention and sales.

"This would start happening on every platform," he says. While new routes to market were opened for small teams, Antonsson identified a growing need for "someone with a detailed understanding of how to cut through the noise".

He could also see that traditional publishers wouldn't be the ones to do it. "The publishing models that existed at that time were archaic," Antonsson recalls. "They didn't fit small, nimble teams, both in how relationships were managed and in the terms [of the contracts] themselves. Their terms and publishing agreements came from an environment where you are shifting boxes. They are tied to those sorts of logistics. You try to apply that to developers who are just a single person making a game, and it just doesn't make sense." Raw Fury would write a new deal for game developers. But first it needed a game to publish.

Kingdom comes

When Thomas van den Berg first released Kingdom in October 2013, it was as a free Flash project, presenting a minimalist strategy game that put you in the stirrups of a monarch astride their noble steed.

Reduced to just a 2D plane, your only controls were to move left and right and drop coins to recruit vagrants to your settlement or pay to construct the sturdy walls you needed to defend against nightly raids.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The Flash game found fans and received adoring writeups from big publications, inspiring van den Berg to come up with ideas for fleshing his game out further and turning it into a full commercial release. At the time, there was an established path to make it happen: he would take his project to Kickstarter, raise the funds to expand it into a full PC and mobile release, perhaps even shoot past his funding goal and add writer Chris Avellone as a human stretch goal, and then he could self-publish Kingdom to Steam. "Do full, true indie," van den Berg tells us.

Milestones can be distracting

Jónas Antonsson

Except, after pairing up with another developer, Marco Bancale, and launching their campaign in May 2014, the crowd of funders didn't materialize. Van den Berg sought €8,000 but after 30 days had barely scraped past the €4,000 mark. "I'm not great at marketing," he admits. The conundrum highlighted the offer Raw Fury could make.

"I knew the magic that was there," Antonsson says. "I played the Flash game like crazy without ever knowing Thomas." Yet a stroke of luck put him and van den Berg in touch. Bancale, van den Berg's co-developer, had worked at Gogogic. When they launched Kingdom's Kickstarter campaign, Bancale contacted Antonsson for advice.

"He pings me out of nowhere," Antonsson recalls. "‘I'm working with this young guy. He's absolutely brilliant. Do you have time to give us some advice?'" The three arranged to meet, and what was supposed to be a half-hour chat took up an entire afternoon. "I was just blown away by Thomas," Antonsson says. "That conversation had a huge influence on me."

Antonsson already knew he would leave Paradox to start a new company. "I'm a serial entrepreneur," he admits. But he had assumed it would be to start a development studio. "I thought being a developer would be my calling forever. But then I started meeting up-and-coming developers doing things I would have never thought of – renaissance men when it came to development."

While it shook Antonsson's belief that he should remain a creator, he also saw something else: "I understood that I could be the support act. I realized Raw Fury needed to exist."

Getting the band together

When Antonsson and his partners put pen to paper on their plans for Raw Fury in January 2015, he reached out to van den Berg and asked if he was willing to be the first.

With Raw Fury's backing, van den Berg could turn his Flash game into a complete experience. As he and Bancale worked on Kingdom, Antonsson wrote the publishing agreement that would serve as the bedrock for all of Raw Fury's future dealings, and set it apart from its many competitors.

The contract didn't just reflect the business in 2015 – accounting for digital distribution, longtail legacy sales, post-launch support, and DLC – it broke from tradition in three key ways. There would be no production milestones, royalties would be split 50/50, and the developer would retain IP ownership.

"Milestones make sense when you have a physical distribution pipeline," Antonsson says. In a system when you are booking time with a disc manufacturer, space in a warehouse, and collections and deliveries to retail stores across the world, you need firm delivery deadlines or risk knock-on costs.

But, Antonsson argues, these things are out of date in an age of digital distribution. Worse, they affect game development in unintended ways. "Milestones can be distracting," he says. "It's easy to focus on hitting the next milestone because a payment is tied to it, rather than [advancing] the game itself."

Raw Fury's founders considered it essential that the developer retain the IP to demonstrate their faith in the project. "If you're the developer, we are buying into your vision," Antonsson says. "We signed your game because we truly believe you're making something amazing."

The revenue share, too, Antonsson argues, demonstrates commitment. "We wanted to sign games and be there for the long haul," he says. "Not just for the launch." A perpetual even split shows that both sides will continue working to grow a game, ensuring it is looked after for as long as it needs.

"I wanted to figure out how to make a contract that reflects what we're trying to achieve as a business," Antonsson says. More importantly, though, he wanted to create an agreement that every developer would sign. "If the point is to create a relationship where there's trust, don't start by going through negotiations where one side feels that they lost something, or wonder if they got a good deal. If you work with indies and smaller developers, you must do that in partnership."

Meet the team

We had expectations that were, I would say, lofty.

Jónas Antonsson

Today, when Raw Fury signs a new project, it creates a publishing cell dedicated to the developer and the game.

The publisher-side group provides marketing and production support, delivering whatever the developer needs to realise their game. "It's really important [for the developer] to meet the team they're going to work closest with," Raw Fury game director Angelica Norgren says. "The needs of a small one-person team will be very different from one with five or six people who've done a bunch of games."

In the early years, Raw Fury's was more of an all-hands-on-deck undertaking. "In the beginning, it was the [founders] doing everything," van den Berg recalls. At shows, he would run the booth with Antonsson, Van Dyke and Martinez. "We were very close and everything was handled in a personal way. A lot of care went into everything."

However, even with their experience and industry connections, Raw Fury was still a new publisher in the process of setting up, trying to cut through the growing noise of thousands of new game releases with a minimalist RTS that had already failed to meet the target of a modest Kickstarter.

"We knew we had something," Antonsson says, having not allowed the crowdfunding failure dampen his forecasts. "We had expectations that were, I would say, lofty." "I would have been satisfied if it broke even," van den Berg says. "I was happy building something that would make back the investment." "Within 24 hours, our expectations were blown out of the water," Antonsson says. As of May 2019, Kingdom and its sequels had sold more than 4m copies.

In the years that followed, Raw Fury and its portfolio grew rapidly. In 2016, it published the point-and-click adventure game Kathy Rain, the painterly side-scrolling shooter Gonner, and Kingdom: New Lands. "In my mind, New Lands is like a relaunch of the game I wanted to make originally," van den Berg says. Raw Fury gave it away as a free update to owners of the first release.

Then came Super Mario Bros 2-inspired platformer Uurnog Uurnlimited, brutal one-hit-kill shooter Tormentor X Punisher, diorama-like realtime tactics game Bad North, and Roguelike cover shooter West Of Dead, in which you play a skeleton with a flaming head, voiced by Ron Perlman. There seemed to be little rhyme or reason to what could be called a Raw Fury game.

"It was a little bit of altruism," Antonsson says. "Every creative medium has two sides – the written word can create Of Mice And Men or a manual for your Samsung refrigerator. At its best, creative mediums can fundamentally change you. That creativity lives and breathes in gaming, and it's needed. One of our core tenets is that sometimes you will find a game that just needs to exist in the world."

After five years, Raw Fury had proved itself a successful publisher. It had released more than 20 games, opened its own studio in Croatia focused on porting its catalogue and supporting its roster of external developers, and even bought the rights to the Kingdom series in order to develop new sequels in-house. ("I had been drawing little pixel-art knights and archers for six years," van den Berg says. "I was happy to trust Raw Fury with the series.")

Crossing the T's

Against this backdrop of success, it was time to return to the original goal of dismantling how publishing traditionally works.

On December 23, 2020, just in time for Christmas, Raw Fury shared its publishing agreement online for all to read. It also shared its templates for financial projections, competitor research, outsourcing agreements, and many other documents developers rarely see before signing with a publisher – or after.

Antonsson says that business development information in the video game industry is like "a little black box". The opacity keeps power out of developers' hands. How can a studio know if a publisher is offering a good deal if it's never seen another deal to compare it to? In making these materials public, Raw Fury was attempting to redress the balance. It was a move that attracted widespread praise, but naturally it also allowed the publisher's terms to be scrutinised.

One stood out in particular: developers wouldn't receive any revenue until Raw Fury received 100 per cent of development costs, a 15 per cent markup, plus publishing services and marketing costs. It was a publisher-protecting term from a company that consistently spoke of being developer first.

For developers, it means they need to find financing to survive between launch and earning out, to still be operating when they receive their share of the 50/50 royalty split.

I wanted to create a publisher that [could] do this over and over and over again.

Jónas Antonsson

Clifftop Games, developer of Raw Fury's second game, Kathy Rain, faced this problem upon its release, with slow initial sales putting the studio's future under threat.

Raw Fury acted swiftly and stepped in to continue funding it for another 12 months, bridging the gap between release and sales picking up. No extra terms were tied to the funding; the IP remained with Clifftop, and the developer could take its next project elsewhere. In all, it took only three months for Kathy Rain to start earning royalties.

Developer Joel Staaf Hästö chose to bring his next game, Whispers Of A Machine, to Raw Fury, and is now working on a Kathy Rain sequel, but it still raises the question of whether the terms match Raw Fury's ethos. If the terms were more generous, would Raw Fury have had to step in at all?

"We come in early and we fund everything," Antonsson says in defence of the agreement. "Not just the game development, but whatever services are needed – the marketing, porting, voiceovers. It's an investment. It's risk. It's about sustainability. I wanted to create a publisher that [could] do this over and over and over again. If you look at our terms in their entirety, there's an inherent promise to support developers – a perpetual 50/50 split after [they earn out]."

There are certainly more successes than failures. After ten years and 50 games, 72 per cent of Raw Fury's portfolio has earned out. "Thirty-six of the games we've signed and released we are paying royalties on," Antonsson says.

"We are still working actively on games that were released years ago, because our contract incentivises us to do this, which is good for us and good for the developers, and it allows us to be sustainable, to sign games over and over and over again."

Cashing in

Antonsson is a bullish defender of Raw Fury's publisher agreement, with good reason. In 2020, as the world went into lockdown, money poured into the videogame industry.

"I remember DICE in 2020," Raw Fury's new CEO, Pim Holfve, says. At the time he was head of Avalanche Group, whose studios created the Just Cause series and The Hunter. "It was insane. The offers came in from random people who just wanted to dig for gold in the games industry."

"There are a lot of smart people that see the potential of this industry from the money side of things," Antonsson agrees. "There's been an overinvestment that has made the last couple of years extremely tough."

"When money was free and the games industry was treated like the Powerball lottery, and people didn't care about the price of the ticket, it got lost that there had to be a return on this insane amount of money," Holfve says. "This is where Jonas and the team relied on common sense."

"I'm not going to sit here and say we did everything perfectly," Antonsson says. "We're a ten-year-old company. We've clearly made mistakes." But, he argues, Raw Fury "recognized some dangers earlier than others". What kept the company safe from some of the industry's recent lurches, though, is one of its core principles: "the deal is the deal is the deal".

The offers came in from random people who just wanted to dig for gold in the games industry.

Pim Holfve

The availability of cheap financing gave developers greater negotiating power, while publishers became more willing to sign games on inflated budgets.

Facing developers fielding multiple offers from different publishers, Raw Fury held firm on its commitment to the publisher agreement it had signed with all of its partners. "We lost out on some games," Antonsson admits. However, negotiating on those terms would have left Raw Fury more exposed if the games had been delayed, cancelled, or launched without finding an audience.

Antonsson kept track of the projects he'd passed on. "In some cases, the publishers that signed those games no longer exist," he says. "We could have fallen into that trap, and thankfully we didn't. We stayed true to our path and principles, and ultimately that's been to our benefit." It's small comfort: "Pim and I have friends who have lost their jobs, their companies."

Raw Fury's contract didn't make it immune from the industry's heady peaks and painful troughs; it only lessened the risk. Still, it sought greater stability, and it found it in 2021 when Altor Equity Partners bought a majority stake in the publisher.

"It was obvious that PC, console – everything – would end up like mobile," Antonsson says. "Little by little, the problems would compound into curation and discovery. To create something sustainable and tackle that problem, you must be a certain size. [Investment] gave us the ability, stability and flexibility to be here now. We're the same publisher. We're operating in the same way."

Profitability comes from us doing a good job

Pim Holfve

Looked at in a certain light, it's a difficult argument to make. For any business, new ownership brings with it new input, new voices, and often a shift away from a company's founding principles.

In this case, it's also notable that it's happening when Antonsson has stepped up to take over as CEO of Combined Effect, the parent company of Raw Fury and publishing labels Neon Doctrine in Taiwan and Kakehashi Games in Japan. But Antonsson says he can prove that Raw Fury is sticking to its guns.

"Sometimes we will sign a game that, if you think about it from any sort of Excel spreadsheet perspective, it's very hard to justify this will make money," he says. "We sign it because it needs to get made and reach as many people as possible, because it's a piece of art. We still do this. The first game we signed when Pim came in was exactly that sort of project. There were no questions asked. We had the capacity, the developer needs to make it, it's a piece of art – we're signing it. Boom."

So, if not sales, how does Raw Fury measure success? Holfve is just six months into his role as CEO but his discussions on the future of Raw Fury have landed on one goal: "Being recognized as the world's best partner for indie developers. Profitability comes from us doing a good job."

"Ultimately," Antonsson adds, "I hope that Raw Fury plays a role in safeguarding the creativity and artistry of the game space, enabling small, independent developers to get their vision made, have their magic shared, and hopefully be able to do that again and again and again."

That's the goal for the next ten years – and presumably many more beyond – but how does Antonsson reflect on Raw Fury's goals for its first decade? "It was not just to make a publisher but to be a catalyst for good," he says. "After ten years, I can say that we've achieved that. And hopefully we'll continue on that path."

Blue Prince is one of the best games of 2025, and our ultimate ranking of the year's finest is filled with fellow huge names this year,

Julian's been writing about video games for more than a decade. In that time, he's always been drawn to the strange intersections between gaming and the real world, like when he interviewed a NASA scientist who had become a Space Pope in EVE Online, or when he traveled to Ukraine to interview game developers involved in the 2014 revolution, or that time he tore his trousers while playing Just Dance with a developer. As well as freelancing for publications such as Wired, PC Gamer, and Edge, he's worked as Kotaku UK's News Editor, PCGamesN's Deputy Editor, and he launched and led GAMINGbible's Snapchat channel, curating the most significant gaming stories for an audience of millions of young readers.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.