Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

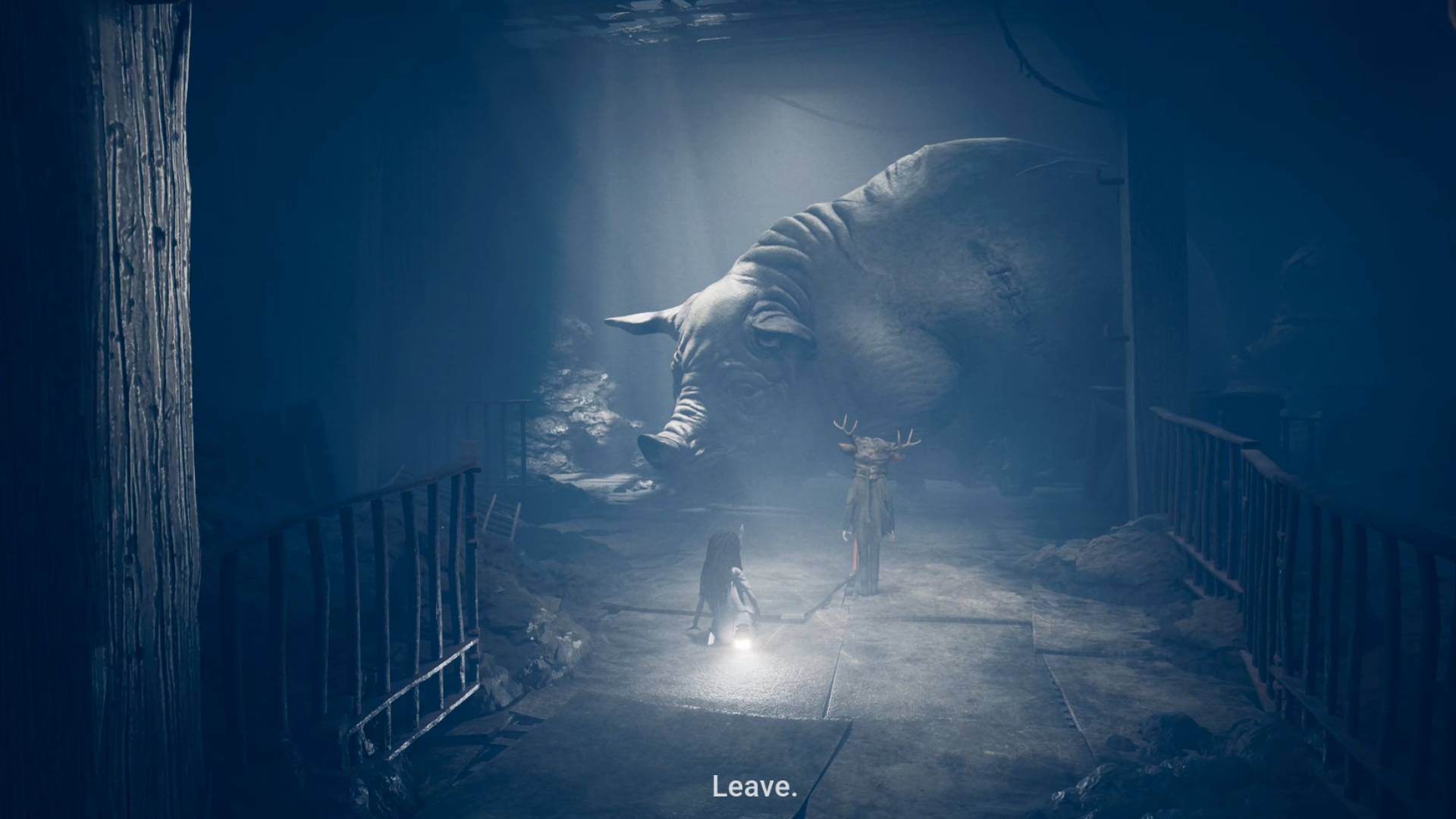

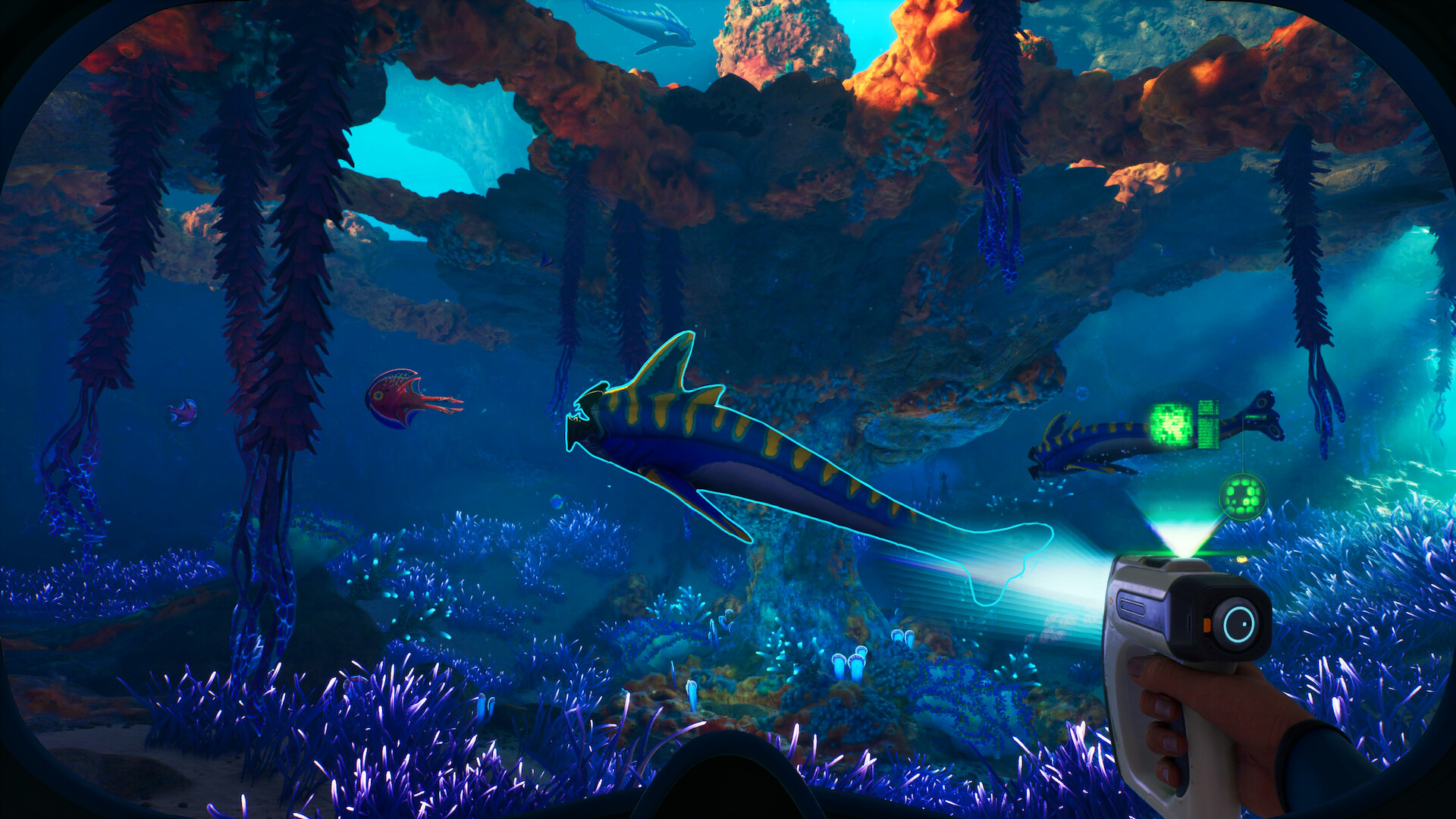

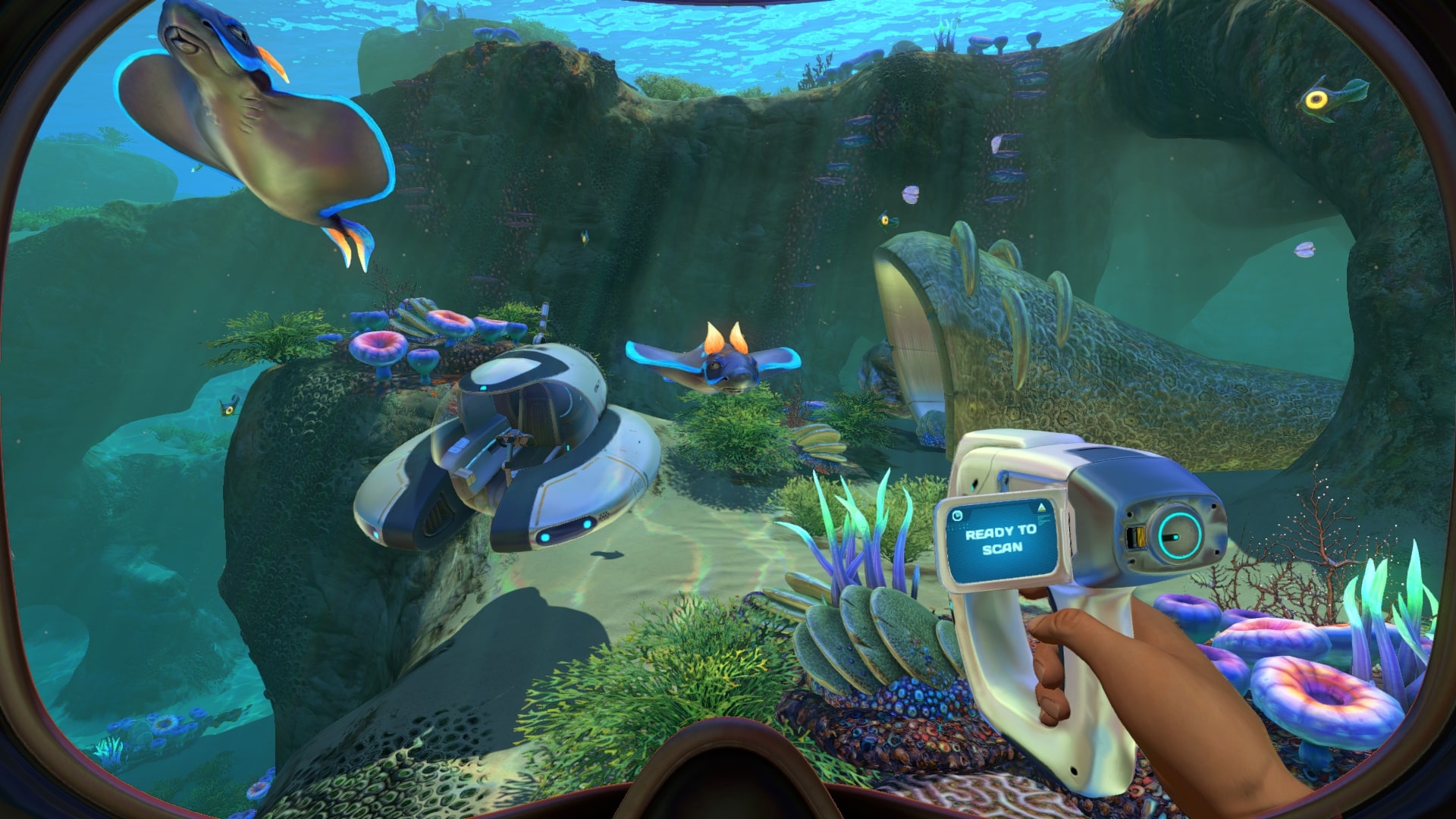

Since Minecraft first burrowed its blocky way into players' brains back in 2009, survival games have gone on to become one of the biggest genres in the medium. The idea of building a shelter and hiding in it from hostile elements and creatures has been adapted into every imaginable scenario, from the depths of the ocean in Subnautica to the farthest reaches of space in No Man's Sky.

The influence of the best survival games can be seen across the industry. Big-budget action-adventure titles such as Tomb Raider and God Of War have adopted elements of survival games – not least the crafting system – while you can trace a direct line from the open-ended zombie survivalism of DayZ to the battle-royale supremacy of Fortnite. Survival games have even changed how videogames, regardless of genre, are made, pioneering the early-access model of development used to create outstanding recent titles such as Hades 2 and Baldur's Gate 3.

Given survival games' ubiquity and influence, then, it might seem absurd to ask whether the genre itself might be dying. Yet as it has grown in popularity, it has also changed dramatically, resulting in a significant shift in both the appearance of games and what's prioritised in them. Consequently, it's possible that survival games are not only dying, but they've reached the brink of extinction without anyone actually noticing.

Dying art

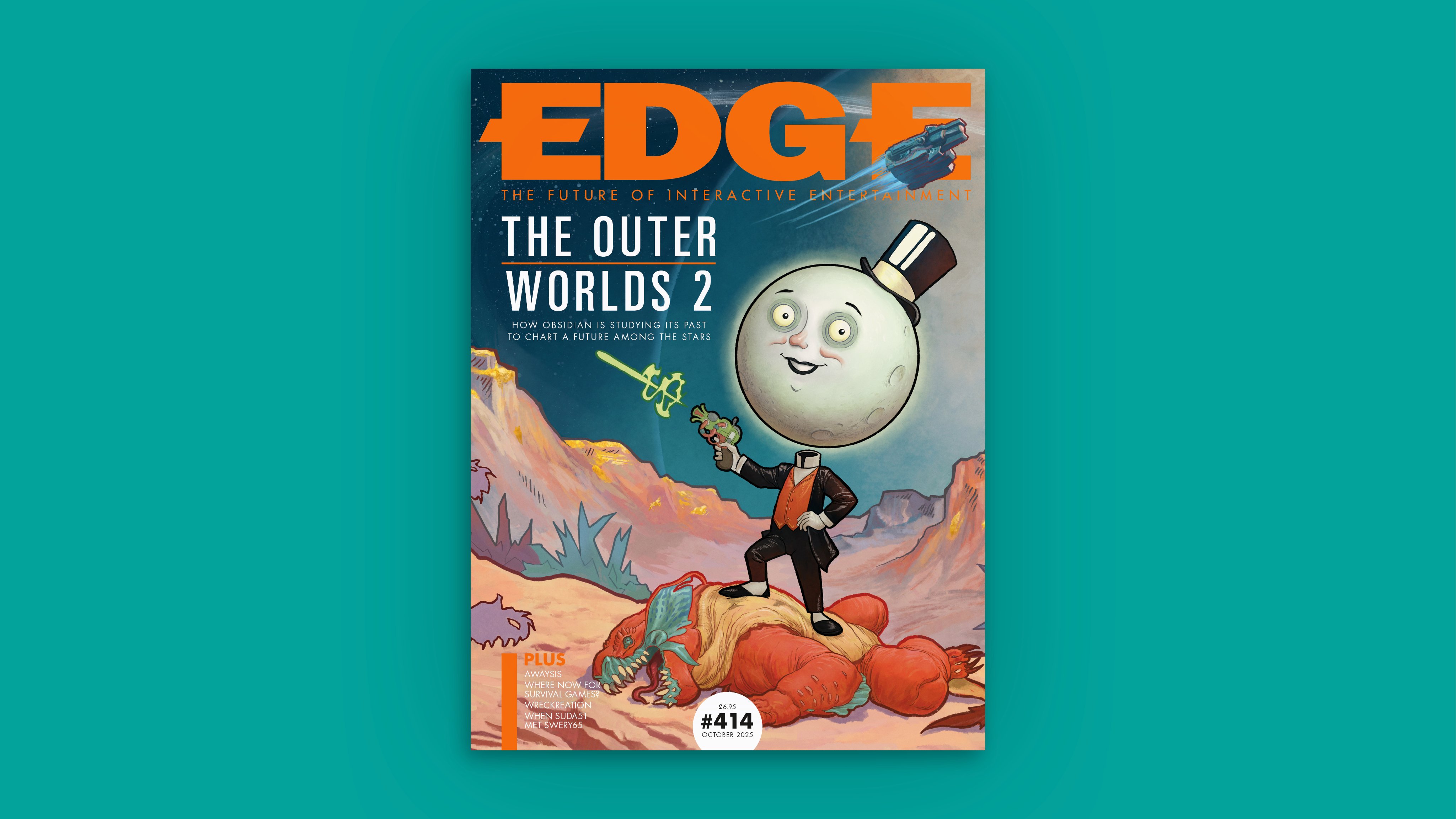

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #414. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

To examine this notion, it's important to specify what exactly survival games are, and the forces behind their appeal and popularity.

Typically, survival games deposit you in a wilderness such as a forest, then challenge you to not die for an unspecified amount of time. At the most basic level, this involves managing various bodily needs such as hunger and thirst (usually represented by gradually decaying meters) by foraging for sources of food and water. Most survival games also allow you to improve your fortunes by crafting tools such as axes, spears and fishing rods, and constructing a shelter where you can store your equipment and hide from wandering creatures and environmental hazards.

The specifics vary between games, but all survival games share the same fundamental draw. Anthony Gallegos, design director on Subnautica 2, perhaps sums it up best with an anecdote.

"I used to work at this one Marvel studio, and we had some coworkers that would occasionally bring their kids to work," he tells us. He recalls seeing one of these children playing Astroneer, a game about constructing bases and outposts on colourful alien worlds. "I was watching this little kid play, and I was like, 'Oh, geez, good luck, kid, that game has no onboarding'. I came back two hours later, and he had made a base that was leaps and bounds above anything I could have fathomed for myself. I was like, 'OK, either this kid's a genius, or survival-game mechanics are just simple enough that they're universally approachable'."

Gallegos believes that the popularity of survival games derives from how they tap into some of our most primal urges. "We're all little monkeys. Everyone's little monkey brains like shelter and food," he says. In other words, just as children build dens in forests and blanket forts in their bedrooms, survival games enable us to simulate the satisfaction of pitting ourselves against the imagined elements.

But this isn't the only reason survival games are so popular. Gallegos has observed that players who discover their appeal also develop an insatiable appetite for them.

"There are a lot of genres where players are very monogamistic. A lot of players are like, 'I only play this shooter'," he says. "MMOs, same way. When all the MMOs were trying to copy World Of Warcraft, people were like 'I'll go play the first free month of it, and then I'm coming back to WOW'."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Whole new worlds

It was an exploration game first, and then they added survival elements

Anthony Gallegos

Survival games, Gallegos believes, are different, as in most cases the vast majority of players don't make a long-term commitment to a single experience.

"If I see people play through all the content of Subnautica and then they leave for a little bit until we do a content patch, that doesn't alarm me, because I know what they're doing," he explains. "They just move from one to [another] with their friends, or by themselves. But they play them all."

When this behaviour started is unclear. What's fascinating, though, is that the original Subnautica is both the product of players' ravenous appetite for survival games and one of the chief architects of the genre's proliferation.

Although it came to be one of the most acclaimed survival games, Unknown Worlds' aquatic adventure was not originally conceived as one. "It was an exploration game first, and then they added survival elements," Gallegos explains. "Charlie [Cleveland], the original creator, if you asked him about it, I think he would tell you that he listened to the community to figure out what they wanted."

Yet in reworking Subnautica into a survival game based on community demand, Cleveland established a template for a new kind of survival game, one that took the genre from its (relatively) grounded origins into the realms of infinite fantasy.

Early progenitors such as Minecraft, The Forest, DayZ and Project Zomboid may all have featured fantastical elements such as zombies and monsters, but their environments all looked like the real world and (more or less) functioned according to real-world logic.

If you needed to craft something out of wood, for example, you went and chopped down a tree. If you needed to cook, you built a campfire or a furnace.

In contrast, Subnautica transposed the fundamentals of survival to an alien ocean world with a unique ecosystem, one in which the lessons learned in those early survival games no longer worked. Instead, players had to master a new set of rules to thrive in the game's planetwide ocean. They would learn how to manage their oxygen, which oceanic creatures were edible, and how to craft items in a world without wood.

In this way, Subnautica demonstrated how a radical change of setting could revitalise survival gaming's underlying ruleset. It's an idea survival games have been riffing on ever since, using setting and theme to recontextualise the underlying mechanics.

Examples that have adopted Subnautica's template include the spacefaring survival sim Breathedge, post-apocalyptic airship game Forever Skies and Obsidian Entertainment's Grounded, which combines survival gaming with a theme inspired by the film Honey, I Shrunk The Kids.

The A Factor

The zombie genre has died – we're bringing it back to life

Geoff Keene

One particularly vivid example from recent years is Abiotic Factor, a cooperative survival game that casts you as a scientist attempting to sustain yourself within a Black Mesa-inspired research facility.

Abiotic Factor's design director, Geoff Keene, had attempted to break into the survival genre during its early years with the ill-fated zombie survival game The Dead Linger. "It was a survival game back when we were like, 'The zombie genre has died – we're bringing it back to life'," he says.

But Keene's inexperience led to a troubled development, while The Dead Linger also struggled to stand out amid a slew of zombie-themed games. "I was young. We didn't know how to make games back then." Keene went on to develop the social deduction game Unfortunate Spacemen before spending some time at DayZ creator Dean Hall's studio, RocketWerkz. But he was still determined to build a survival game of his own, eventually cofounding Deep Field Games with several friends to create Abiotic Factor.

A core inspiration here was the opening tram ride in Half-Life and its second expansion, Blue Shift, occurring before Gordon Freeman triggers the resonance cascade that dooms the facility. "I just love that little slice of life," Keene says. "Who lives there? Who's doing the stuff there?" He imagined a scenario in which you had to survive for a longer period in Black Mesa, living off food pulled from vending machines and building equipment out of the furniture. "That was the original idea. I want trams, and I want vending machines, and I want lab coats."

Though Abiotic Factor is a survival game, only its base mechanics derive from genre norms, with everything else designed to fit its theme. Its setting, the GATE research facility, is structured to reflect Black Mesa's warren of corridors, with excursions into Xen-style portal worlds where you can discover strange new resources.

The crafting system, meanwhile, is designed to make you feel like you're inventing the items you create, reflecting your in-game role as a brainy boffin. "Our marketing producer, she came up with an idea for a minigame that was sort of based on Wordle," Keene says. "We made this little prototype of moving the items into the slot to make the item. You're given six or eight items or something, and you have to guess which ones are used in the recipe."

Abiotic Factor's scientific survivalism shows how Subnautica opened the floodgates to what's possible in the survival space. But as such there's one big difference between the wider effects they had, in using unusual themes to their advantage.

Subnautica's underwater world made it a pioneer, whereas Abiotic Factor's approach is now the baseline a survival game must meet to stand out.

Indeed, according to Keene, the perception of survival games as a robust, enduringly popular genre is built on the skeletons of countless examples that are released into immediate obscurity. "Most survival games go nowhere, right?" he says. "They release and get 100 reviews on Steam, if they're lucky, and then they just fall off the map."

Because of this, one of the key thrusts of Abiotic Factor's development was to steer clear of ideas or motifs that made it resemble a traditional survival game. "I basically avoided anything that makes survival games a real grind – looking at the ground, picking up sticks," he says. "I think a lot of them fall into that trap where they're like, 'Well, we've got the wood chopping, we've got the picking up sticks and stones, we've got the crafting…' You've got to do something different with it."

Survival games often make you want to do anything but lose.

Anthony Gallegos

Gallegos agrees that developers of survival games can no longer rely on the basic tree chopping and campfire building that popularized the genre.

"At the very least, you need a strong theme," he says. But he also points out that the priorities of survival games have shifted more broadly. For example, modern survival games either heavily support or outright mandate cooperative multiperson play. Abiotic Factor already includes this while Unknown Worlds is bringing co-op play to Subnautica 2.

"We have certain mechanics where, if I hit my air [bladder] in singleplayer, it gives me oxygen. If I hit it when I'm standing next to you, it gives us both oxygen," Gallegos says. In addition, he states that modern survival games are increasingly averse to challenging or punishing players, with death and setbacks treated as an inconvenience to enjoyment. "Survival games often make you want to do anything but lose. You're like, 'I will hoard everything for food. I don't ever want to die. I don't ever want to lose. I will save scum'."

And this brings us to why, despite appearances, survival games may be an endangered species. In the effort to diversify, developers might just have forgotten what they're supposed to be about.

Drive to survive

I just find it ultimately pretty tedious

Seth Rosen

This is the view of Seth Rosen, a freelance game design consultant and director who has overseen the development of numerous survival games, including Don't Starve Together (the multiplayer expansion to Klei Entertainment's 2013 hit) and last year's Pacific Drive.

"The vast majority of games we call survival games, I think, could more accurately be described as co-op base-building RPGs," he says. "The fact that it's sort of dressed up as survival and you have a hunger meter is just tacking onto what's hot in the market."

Rosen qualifies his position by pointing out that he personally doesn't like the survival genre, despite having designed two games that would conventionally fall into the category. "For me, survival games tend to be two things. One is a mystery box in terms of there's all this stuff and you've got to figure out how it works in the world, so you are poking things with sticks and seeing what they do," he explains. "And it's also a collect-a-thon. It's a crafting and resource-gathering experience, and that's most of what we're doing moment to moment. And I just find it ultimately pretty tedious."

Within this nebula of crafting and base-building RPGs, Rosen says there are "vanishingly few" true survival experiences. "When I think of survival, the word, and movies that are about survival, it's about a character finding themselves against great odds, often in some difficult climate or terrain or strange world that they don't understand, and they have limited resources."

Examples of 'true' survival games by that definition include Creepy Jar's jungle-based Green Hell and Hinterland Studio's uncompromising arctic excursion The Long Dark. In both games, staying alive is nearly always your primary concern, and the environmental hazards you face, such as extreme cold or wild predators, are a constant threat to your continued existence.

But the trajectory of the modern survival genre, in which modes of play such as exploration, creativity and cooperation have been increasingly emphasised, has deliberately reduced much of this friction. "Especially in the multiplayer variants of these things," Rosen points out, "if you die, the penalty is you have to walk back to your backpack. That's not survival at that point – that's adventuring."

The vast majority of what's going on in Pacific Drive is time management or attentional management

Seth Rosen

As Gallegos observes, many modern survival games perceive the fundamental challenge and busywork of survival as an inconvenience, and there are far more egregious examples of this than the likes of Subnautica and Abiotic Factor, both of which require you to take risks and plan expeditions to improve your situation.

Games such as Redbeet Interactive's Raft enable you to take your entire base with you on adventures, so stepping out for food or other resources demands little forethought.

For Rosen, then, there are many games outside the survival genre that better embrace the ideas it is notionally about, including survival-horror examples. "I think back to Resident Evil 1 and 2, and how hilariously sparse ammunition was. That feels a lot more like survival to me." He also points to 2019's Outer Wilds, and how it challenged players to figure out how its solar system worked in order to escape its time-loop apocalypse that occurred every 22 minutes.

"Outer Wilds is more of a survival game than a lot of what we call survival games," he says. "For a lot of people, it's really satisfying and gratifying to make progress in the tech tree, and improve your walls from wood to stone or whatever. But that's not survival at that point. That's frontiering."

It's worth noting that Rosen's view of how we wrongly categorize survival games extends to his own work. Rosen doesn't consider Pacific Drive to be a true survival game either.

"I think of it much more as a car-maintenance adventure than a survival game," he says. "A lot of our challenges were about figuring out how to put the player into duress mode when they're behind the wheel of a car, which has to protect you to a degree, but also you need to care about the state of your car and maintain it."

That said, Pacific Drive does incorporate many of Rosen's design ideas about how to engender survivalist instincts in a virtual space.

Pacific Drive is all about managing your fuel, your tyres, the overall integrity of your car, and doing so in an environment where there are hazards that can and will harm you. It's a game that is willing to get in your way, and interrupt what you want to do with more urgent tasks that you need to do.

"If you boil it down, the vast majority of what's going on in Pacific Drive is time management or attentional management," Rosen says. "The emotion that is elicited by having to do time management when there are stakes is that fight-or-flight, 'dynamic problem solving under duress' feeling that you get from actual survival."

Getting back on track

Refocusing survival games on actual survival will not be easy. For starters, it doesn't appear to be what the majority of players want.

But in addition to this, making a true survival game that's also enjoyable is very difficult. In their traditional formulation, survival games are built upon a very simple set of systems, namely one or several timers that tick down until they kill the you unless you're able to restore them by some means. Every other system commonly associated with survival games – crafting, base building – is supplementary.

This is what makes survival games so adaptable. You can add these systems into virtually any other type of game, just as Cleveland did with the original Subnautica. But the passive nature of these mechanics also means that making a game specifically about survival is tough, hence why they so often exist beneath other, more interactively immediate mechanics such as crafting and building, and why those mechanics have become more prioritised over time.

I think it's detrimental to survival games to keep trying to copy other survival games

Geoff Keene

With that in mind, what does the future hold for survival games? Rosen believes that bringing survival back to the fore requires better delineation between survival games and crafting/base-building RPGs, though he acknowledges there are obstacles.

"I've been working on a talk about all of this, and one of the things I keep trying to fit into it is this new taxonomy for how to talk about these kinds of games," he says. "But it's so multivalent, and it so often multiplies even within a single title, that I found it really hard to nail down the thing, which I think is why we get this umbrella term of 'survival games'."

Keene, however, thinks the opposite, that survival games will only thrive if they continue to mix with other genres. "I would say there needs to be more hybridization," he says. "I think it's detrimental to survival games to keep trying to copy other survival games. They really need to step out and do more things with it."

Gallegos, meanwhile, falls somewhere between the two. He predicts survival games will become even more focused upon multiplayer, likely taking inspiration from viral hits in the cooperative horror space. "Survival games will increasingly lean into more social mechanics over time," he says, "learning the lessons from major successes like REPO and Content Warning, and looking at the ways people play together."

This is something Unknown Worlds plans to pursue with Subnautica 2. "In the original version of the prototype, I could stand in the doorway to the big sub and block it and just watch you drown. I would do stuff like that all the time, where they'd be like, 'Let me in', and I'd be like, 'What's the password?'" he says.

"We got rid of that for now, but I think we'll be finding ways to bring stuff like that in, ways you can lightly mess with each other, like if we added a mechanic where, when you're swimming to the surface, you could grab someone's ankle and use it to pull yourself past them."

Scrapping for parts

But Gallegos doesn't believe this means survival games will necessarily stray further from their origins. Instead, the right kind of hybridization could reinstate the tension of survival to the genre.

He points to the recently released co-op indie Peak as an example. "It's a climbing game, but you only have a stamina bar," he says. "If you take health damage, it impacts your stamina bar. If you're hungry, it slowly impacts your stamina bar even more. So you eat to get it back to where it was. You heal yourself to get your stamina back. That's a brilliant way to tie all these survival systems into [one] thing the player cares about."

Gallegos also points out that Unknown Worlds plans to elaborate upon the basic survival systems Subnautica 2 will initially launch with. Appropriately, one of the sequel's central themes is adaptation, with players altering their characters at a genetic level to better thrive in its underwater world. Some upgrades will give players access to new areas of the world, while others, planned for the future, will enable them to customise their characters in more specific ways.

But, coming full circle, the extent of these adaptations will depend on how Subnautica 2's community responds to them. "We're definitely going to push our systems over time, but I think we're going to push them more in the terms of [how] hunger will play into this progression system, [or] thirst will play into that progression system. But reinventing those entirely? I'm not sure," Gallegos says.

"We'll have to see. If the fans, in our case, really want us to push it, we will." Survival, after all, is a matter of understanding the environment you exist in. And sometimes the best way to do that, ironically, is to evolve into a different kind of beast.

Check out all the new games of 2026 to look forward to in the next 12 months, from Resident Evil Requiem to GTA 6

Rick is the Games Editor on Custom PC. He is also a freelance games journalist whose words have appeared on Eurogamer, PC Gamer, The Guardian, RPS, Kotaku, Trusted Reviews, PC Gamer, GamesRadar, Rock, Paper, Shotgun, and more.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.