6 years after Untitled Goose Game's viral success, its devs seek solace in a chill co-op puzzler: "We were building the game around ourselves as we went"

Interview | If Untitled Goose Game was a "precarious house of cards", Big Walk offers a "looser, more permissive" space to play with friends

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

You surely don't need to be told that 2019's Untitled Goose Game was a surprise hit for its developer, House House. Nor, most likely, do we need to describe how that game managed to perfectly capture the essence of an English village, in its hedgerow-delineated serenity and simmering resentments alike. But did you know that its creators were adapting this place from the far side of the globe, in Melbourne?

House House's followup, Big Walk, brings the developer back home – specifically, to Wilsons Promontory, a national park at the southernmost tip of mainland Australia. "It's a big granite isthmus that sticks out into the ocean, so it's got quite a unique biosphere," says Jake Strasser. His full explanation includes terms such as "Lower Devonian granite", underlining just how seriously House House takes its silliness.

The developer has recreated Wilsons Prom (as the locals call it) at a 1:20 scale using lidar scans of the real place, and populated it with authentic flora based on photographs the team have taken on research trips. Now we find ourselves on a field trip of our own, being guided through this virtual recreation by its four primary architects.

Take a hike

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #412. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

Strasser delivers his geography lecture from a thin bench on one side of a train, his legs dangling precariously as scenery whizzes past. Wilsons Prom has personal significance to all four developers, who grew up a couple of hours' drive away, but to Strasser in particular. He gestures to a point on the coast, revealing – somewhat shyly – that this is where his partner proposed to him.

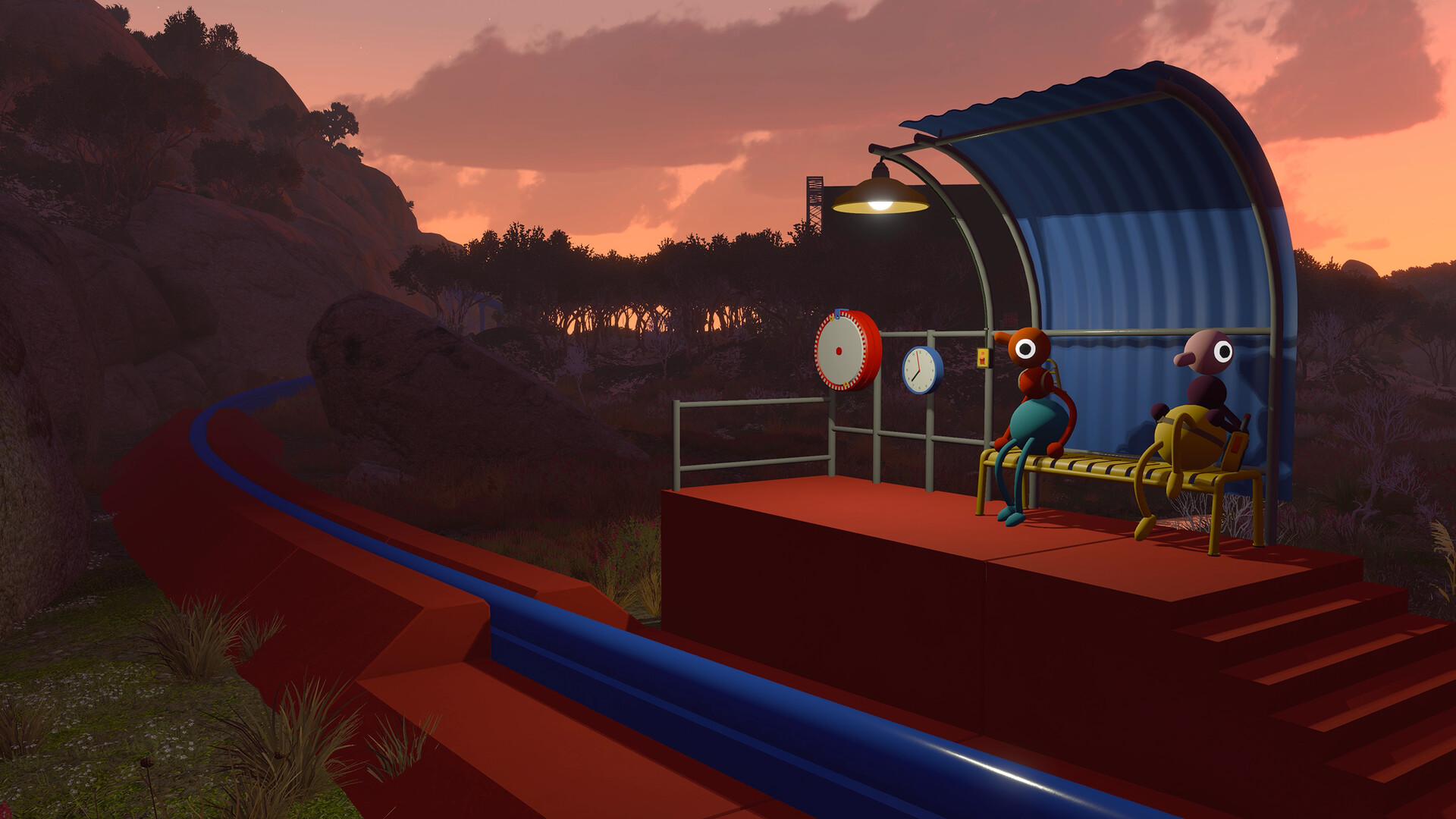

"It just has a real magic to it," Strasser concludes. Meaning, of course, the actual Wilsons Prom. But looking around us – at the mountains towering overhead and the granite-studded slopes that melt gradually into the sea, not to mention the brightly coloured architecture dotted across the landscape – we'd say the same thing about this virtual version too.

It's at this point that one of our tour guides hits the train's brake button, bringing us to a sudden halt. Another scoops up a glowing ball, pulls back one leg and holds it there, quivering. We have just enough time to identify the owner of this leg as Nico Disseldorp (our guides have helpfully colour-coded their avatars, with dark charcoal ‘uniforms' and a single pop of colour up top – Disseldorp's is a pale pink) before he releases.

"I just kicked that as a goal," he declares, pointing downhill at the ball's soft red light tumbling into the bush. Disseldorp then leaps from the train, and everyone follows, sliding down the hill on our backsides.

This is far from the last conversation we have in Big Walk that takes a turn towards the deep and meaningful before being suddenly interrupted: by the accidental firing of a flare gun, or one party sliding off a cliff edge, or someone activating a turnstile that traps them inside a puzzle chamber.

Moments of gentle beauty that crash headlong into something raucous and goofy – such collisions are Big Walk's stock-in-trade, and we can't get enough of them.

On tour

This developer-led tour, we should note, isn't actually our first time inside Big Walk. Let's hop back in time to a few days earlier, when a group consisting of half a dozen players from the Edge extended family are set loose on the island, without any chaperones or explanation of what we're supposed to be doing. (We're the first group to do so totally unmonitored, Disseldorp will later, rather nervously, explain – prior to this, only the playtesters, and the developers themselves, had wandered through these builds.)

The results are chaotic. The sole guidance we've been given is that we should try to reach "the red tower", something we're told generally takes about an hour. After the best part of ten minutes, we've yet to leave the lobby area all players spawn into at the beginning of a session.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Primary-school diagrams on the lobby wall introduce the many available verbs, which range from the highly mobile (run, jump, pick up, dropkick) to the more sedate (point, press, sit). Soon enough, our group is testing the elastic limit of these actions. Can you pick up another player? Yes. Without permission? Absolutely. Can you dropkick them? Not very far.

We're very interested in being a body in the space of the games we make

Stuart Gillespie-Cook

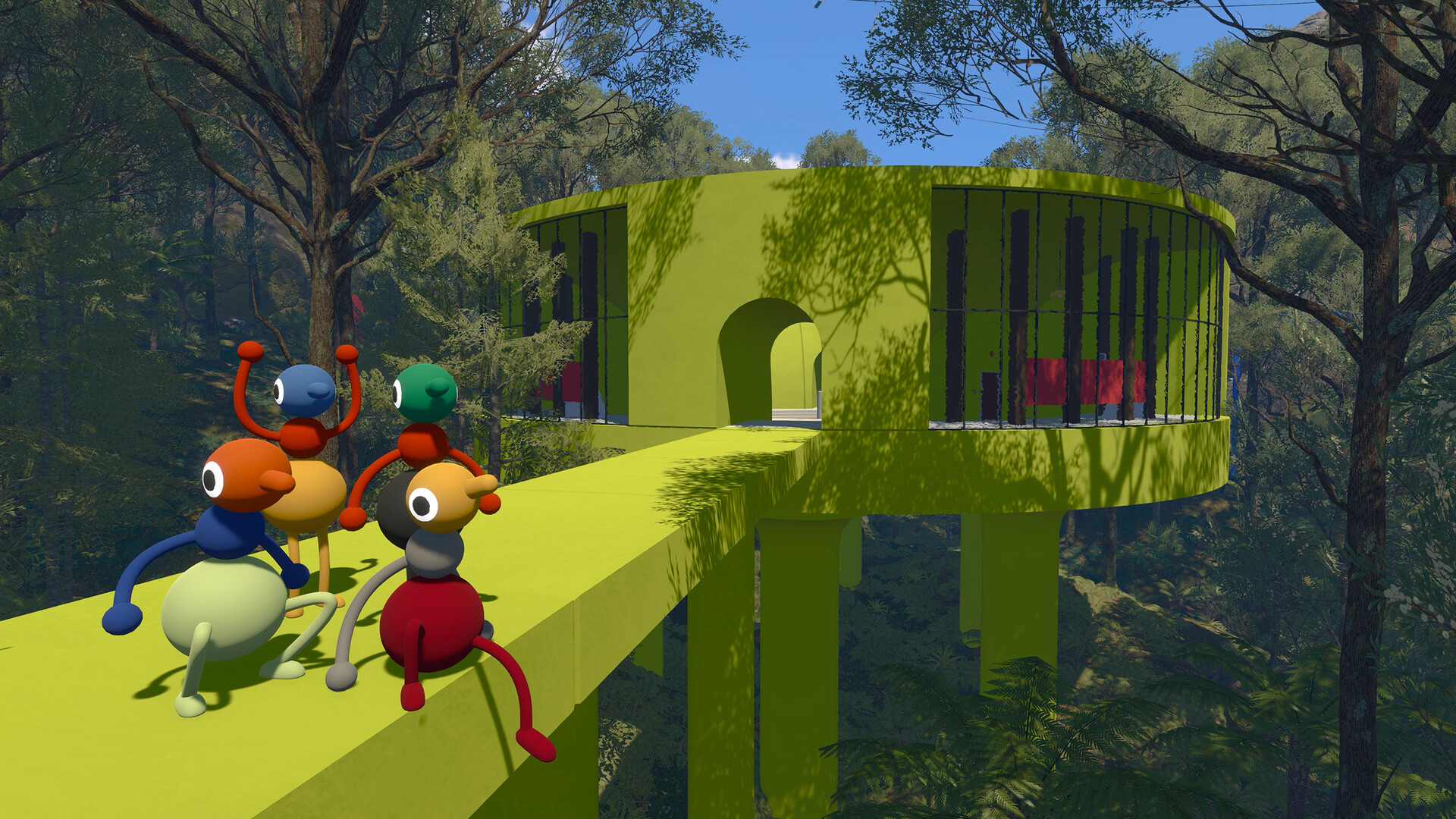

These experiments do prove to be useful, however, once we eventually make it outside. The view that greets us is a low valley of scrubland, with a river snaking through it towards the sea, and a handful of colourful adventure-playground structures. These are the first of Big Walk's puzzles – and the very first one has us picking one another up, clambering on shoulders to form a mobile tower of bodies.

The player on top presses a previously out-of-reach button, and – in an explosion of confetti – we receive our prize. You get the same one for solving any of Big Walk's puzzles: a rubbery red macguffin of a shape somewhere between a matryoshka, snowman and jelly baby. Earn enough of these things (they have no official name, Disseldorp later confirms, or at least not one House House is willing to say publicly) and you can trade them in for a key.

Carry that between a few key-cutting stations and you can use it to open a door. Beyond that door awaits the rest of Big Walk's world, its spaces and challenges ready to be tackled in any order you fancy.

You might recognize this structure: it essentially follows the pattern of Breath Of The Wild's opening sequence, which leads you from the Great Plateau into the wider open world of Hyrule. Well, if you're going to steal, you might as well make sure it's from the best. And that's a philosophy House House certainly seems to have embraced here more broadly.

We identify a touch of Journey in its off-kilter approach to multiplayer exploration and communication. The artifice of puzzles nested in beautifully rendered nature, meanwhile, recalls Myst or The Witness – but with the latter's portentous quote snippets replaced by the easy nattering of friends, and the puzzles occasionally swapped for simple, joyful toys. "Takehashi's going to spit out his drink," one of our companions says, as we arrive at the next bright plastic structure, pick up a gigantic paintbrush and begin colouring in one another's bodies.

Those bodies are as simple as the doodles that spawned them: three circles arranged on top of each other, with rubber-hose limbs. Their heads are spheres with one enormous flat eye on either side and a cylindrical trumpet emerging as their mouth. As the controlling player speaks, it quivers in a manner akin to the noot-nooting of Pingu's beak. So they're birdlike, these creatures (and House House obviously has some previous there), but also insectoid?

Our characters are as perfectly expressive as the very finest doodles – a necessity, given that many of the game's puzzles rely on the ability to mime legibly. And for all their lankiness, they're also agile, right down to the aforementioned backside slide. Ignore the firstperson perspective – is that a touch of Mario we detect?

"We talk about Mario 64 a lot," Stuart Gillespie-Cook confirms. The developer's avatar is sitting the wrong way around on a sofa, one skinny leg resting along its top, as he adds: "We're very interested in being a body in the space of the games we make." This is a theme that runs through all of House House's work. Its debut, Push Me Pull You, had players steering the opposite ends of a creature with two sets of heads and arms – one at either end of a long, intestinal body – often becoming wrapped around one another and their competitors.

But it was while working on the movement of Untitled Goose Game's avian antihero that the studio first turned to Mario. Gillespie-Cook waxes lyrical: "There are a bunch of different little modifiers that have all different affordances to how Mario moves around, that make him so expressive." Disseldorp ribs his colleague – "that's definitely your thing, Stu" – before joining in himself, enthusing about the way Mario 64 lets you crawl along like a baby, with no clear benefit to the player or justification for existing. "Lots of the things Mario can do in that game, they seem almost solely performative."

That effect is, of course, multiplied when you've got a group of other players right there to perform to. The devs demonstrate some of the more useless things that can be achieved with Big Walk's controls, should the mood take you.

One drags their character's bulbous abdomen across the floor like a dog with worms. Two of them hold out their arms for a makeshift embrace, then – as they get closer and closer – make smooching noises to wobble their beaks. Actions with no clear benefit or justification for existing, aside from the very best one: making each other laugh.

Cooperative society

While Big Walk is on one level a cooperative puzzle game, you can more or less ditch this aspect entirely and instead play it as a kind of open-world hangout simulator.

So it's no great surprise to learn when and how the game's development began: in 2020, while the members of this tight-knit team were separated by lockdown. "The meetings we had in the game were the only meetings we were really having," Gillespie-Cook explains. "This was just our way to hang out, for so long. Which is a very interesting way to discover the boundaries of your game, and what's interesting about it."

At the time, the team didn't necessarily expect this to become House House's next commercial release. "It felt like we couldn't really start a big videogame project when we couldn't even meet," Disseldorp says. Now it's Gillespie-Cook's turn for a spot of good-natured ribbing: "That's maybe a necessary lie we tell ourselves at the start of every project. ‘This one's just gonna be a few months, just something to dust off the cobwebs – we'll learn some new skills and then we'll make the real thing'."

This was just our way to hang out, for so long.

Stuart Gillespie-Cook

Whatever the case, this project was originally intended as "something little and social and just for us," Disseldorp says. "And then, as we started playing it together, we just kind of fell in love with it and decided we wanted to do it justice." The conversation is turning heartfelt – and so, in accordance with the immutable laws of Big Walk, something brilliantly silly occurs.

As his colleague is speaking, Gillespie-Cook's avatar suddenly stands upright, his body goes stiff, and his eyes become X'd out – the universal cartoon language for ‘dead', or possibly ‘drunk'. "He's lost connection," Disseldorp laughs, in explanation. (Incidentally, when disconnections cause players to freeze like this, their bodies can be dropkicked. Sometimes experimentation takes a while to pay off.)

As we all wait for our companion to come back to life, Michael McMaster picks up the thread of Big Walk's origin story: "We were building the game around ourselves as we went." It was freeing, he says, after the "precarious house of cards" that was Untitled Goose Game's village, with its crisscrossing mission chains, to have a "looser, more permissive" space to play with. "One kind of tree everywhere, a couple of buildings, and there's your videogame."

This description no longer fits the rather gorgeous place we're exploring, of course, but that early "quick and dirty" version was enough for the team to become smitten with what they were making and begin experimenting outwards. "I don't think we really knew what the game was going to be for the first two years of making it," McMaster admits. "We had this big, open terrain, and we made these characters, and we added proximity voice chat, and then we walked around in it a lot."

Let's rewind a little once again. It's taken us a while to mention this because, as Strasser puts it, "the mechanics we're interested in exploring are things that we just take for granted in regular life," if not in most videogames. But Big Walk is part of a rising trend of titles that insist you set aside Discord and instead rely on their in-game communication tools, so that you only hear the voices of players standing nearby.

"It's been interesting, watching a bunch of other proximity voice chat games come out and become very popular in the time we've been working on this," Gillespie-Cook says. "At first, it was kind of scary – like, ‘Oh, have we missed this wave? Are we going to be referred to as, like, a Lethal Company clone or whatever?' It's maybe fortunate that we've been exploring very different parts of what makes proximity chat interesting."

House House's particular areas of interest here can be split into two categories, neither of which have much at all to do with survival horror, and instead align with the game's twin identities as a multiplayer puzzler and a virtual hangout spot.

The mechanics we're interested in exploring are things that we just take for granted in regular life

Jake Strasser.

The latter use case, it seems, arrived first. "We realised early on, the first couple of times we played this game together as a group, that there's something very special about the amount of attention you have to pay each other," Disseldorp says. "Just being a group together was the game, and it had real stakes."

Keeping a conversation going while on a trek means ensuring no one in the group is rushing ahead or straggling behind the herd – something that gets all the more complicated once night falls, and you're trying to navigate forests in the pitch dark. "If you get split up," Disseldorp cautions, "you have to figure out what to do next." And generally without being able to hear or see one another.

All this is assuming, of course, that the party even wants to regroup. During our first, unguided session, one member of the Edge group can't resist wandering off on their own. The rest of us spend much of our time solving team puzzles without them before, the best part of an hour later, this lone wolf strolls back into earshot bearing tales from the far side of the island. "Now and again, watching playtests, you'll see a loose unit like that," McMaster says. "Just like, ‘I'm gonna do my own thing'."

It's not necessarily the player archetype House House was planning for but, Disseldorp says, "I think it kind of works. They get to play the game they want, and your game is richer for knowing that they're out there somewhere while you're playing." You might come across radios and walkie-talkies, allowing you to communicate across the breadth of the island, but otherwise these wandering players become a kind of Big Foot figure, spotted from afar or only ever visible by the evidence of places they've already been.

Lights that have been activated to illuminate a path, an item dropped after they presumably found something more useful – these become little nuggets of user-generated environmental storytelling. "You're almost tracking them, detective-style," Gillespie-Cook says.

It's good to talk

We're kind of using the video game level to make a bunch of different little folkgames

Nico Disseldorp

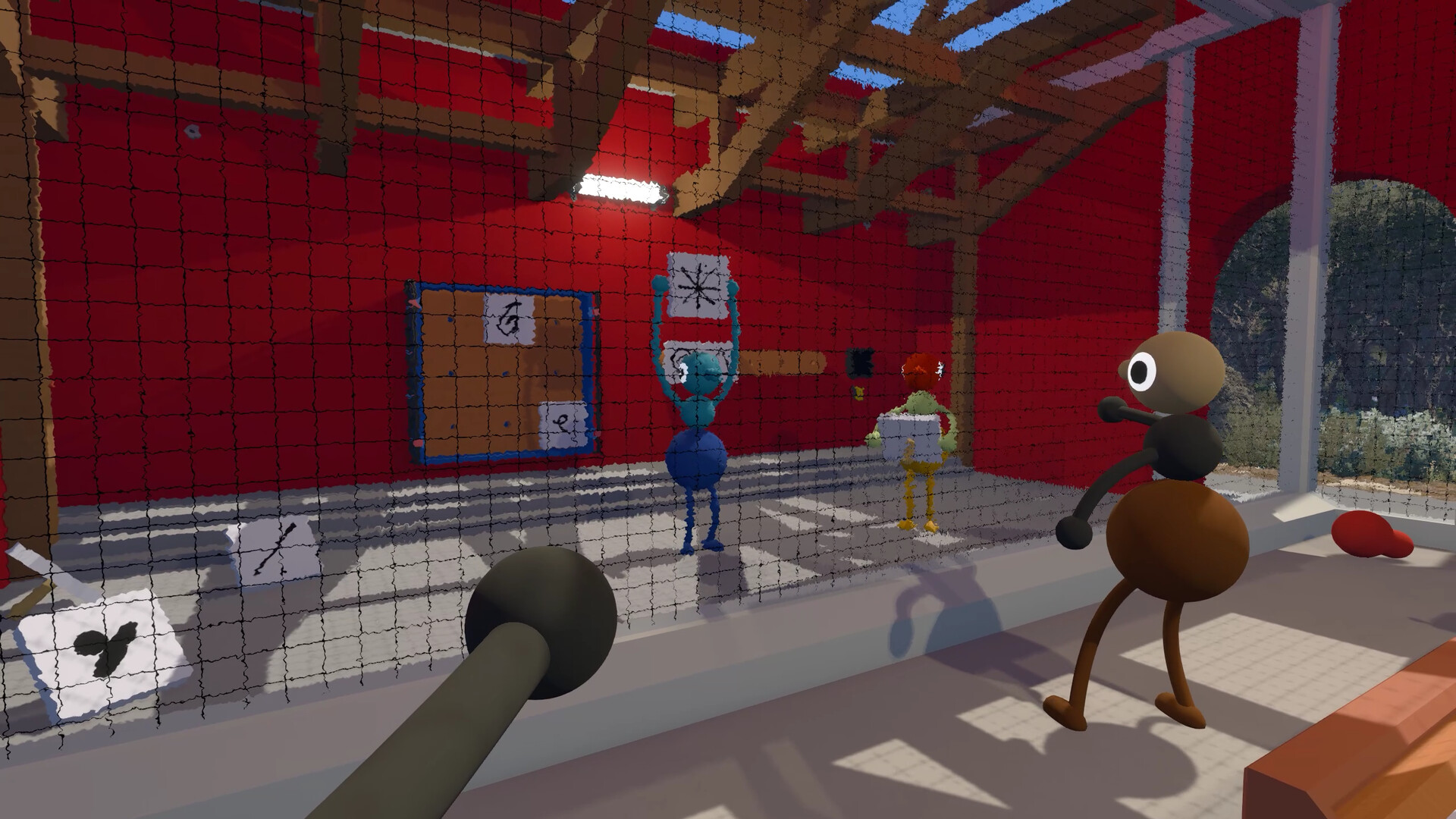

Underlining the sense that proximity chat might be the single most important mechanic in Big Walk, it's also core to many of its puzzles (or ‘challenges', as House House prefers to call them).

The physicality of our first, with all that shoulder-clambering business, seems to be the exception rather than the rule. Most challenges we encounter are rooted in communication – and miscommunication.

You might, for example, be shouting directions to a blindfolded player trying to navigate an obstacle course, or be forced far enough apart that you can't hear one another and must use your avatar's full moveset to mime. There are challenges in which you work together to invent a shared memory palace, and others that are essentially just one-off gags. (One gets a real belly laugh. "A lot of people say it's their favourite challenge in the game," Disseldorp says, before asking us not to spoil the punchline.)

Perhaps the most quintessential, though, have two players or teams separated by a wall, relaying visual information using only their voices. When we play one of these games with the House House group, Disseldrop describes one scribbled symbol thus: "It's a pair of training chopsticks and a chip. A hot chip." Just to confirm that we're looking at the same one, we offer in return: like a stork's bundle, with the baby worm falling out of it? "You've got it!"

Such descriptions will be familiar to any players of Keep Talking And Nobody Explodes, the excellent co-op VR puzzler in which one player, wearing the headset, sees and prods at a bomb while everyone else flicks through a paper manual with the instructions for its defusal.

That game was part of a larger mid-2010s renaissance in local multiplayer gaming, which played a vital role in House House's origin – though it was actually a different game from that time which first brought them all together.

"We were playing Sportsfriends a lot," Gillespie-Cook reminisces. "Then we started meeting up, almost like a book club, to talk about new local-multiplayer games. And eventually we decided, ‘Oh, we could make one of these, maybe', despite having no prior interest in making videogames up until that point."

That origin is evident in Push Me Pull You, which House House isn't afraid to admit was something of a Sportsfriends tribute act. Untitled Goose Game went in a very different direction – at least, it did before the 2020 update, which added a twoplayer mode (this was, perhaps not coincidentally, what House House was working immediately before beginning this project).

While Big Walk might be played online, it feels like a natural descendant from those couchplay ancestors, following an evolutionary branch where Keep Talking's influence has been crossbred with escape rooms. "We are drawing from Keep Talking And Nobody Explodes and We Were Here and those talking-to-each-other games," Disseldorp says. "But the cooperative escape-room genre was still pretty new when we started making this in 2020." And once again House House's particular set of interests have seen it diverge naturally from the competition.

"We were really keen to try and make the challenges less like puzzles, these contraptions that you're all butting your heads up against until someone has the ‘aha' moment," he continues. "And more like the kinds of social game you might play on a real bush walk – you know, 20 Questions, or Charades, or something like that. So we're kind of using the video game level to make a bunch of different little folkgames, keeping the focus on the people you're with the whole time."

It's the walk that really matters, then, and the people you do it with. The challenges are variously explained as "a thing to work towards, that you could then get distracted from" (McMaster) and "social lubrication, for want of a better word" (Strasser). As Disseldorp points out, "there's nothing worse than having a group phone call with people you wouldn't normally, and then not having anything [else] going on."

For all the videogames we've referenced in an attempt to triangulate Big Walk's unique design, the comparisons that really stick are drawn straight from real life. Disseldorp goes on to liken the game's challenges to the campfire that burns away in the centre of a social huddle: "a cool thing to look at, in the little silences."

In that very first session, Big Walk evokes two very specific sensations we're not sure we've experienced in a videogame before. Losing track of friends then unexpectedly finding them again is redolent of our festival-going days, before mobile networks were robust enough to handle that many people in a single field.

One of the earliest pitches of the game was that it would be like a house party.

Stuart Gillepsie-Cook

Meanwhile, standing just far enough from the group to hear them squabbling over a puzzle's solution but not make out any of the details gives us that contented buzz of being at the edge of a party going well, enjoying the sounds of people getting along before dipping back in.

We put these comparisons to House House. "That's, like, the highest praise we can receive," Gillepsie-Cook beams. "One of the earliest pitches of the game was that it would be like a house party. You'd break off into little rooms and have private conversations with one group and then join up with other people."

It turns out we're not the first ones to make the festival comparison, either. "I was with Luke [Neher], one of the two guys who's produced all the music in the game, last night at the pub, and he described it to another friend as ‘returning to the campsite to cook it simulator'," Strasser says. "Like, it's 3am and you're trying to corral this group of people at a festival."

Later on, Strasser describes the moment he fell for this strange thing they were making: "It was the first time we played music through the [in-game] big screen… What's that song called, Stu?" (It was Hellish Imp, by Belgian DJ Cabaret Nocturne.) "Yeah, what a track. Big sunrise-set dance music, and we're out in the bush listening to this booming bass with the sun coming up. That really felt like we'd arrived at some magic – or captured, you know, an existing magic."

Heading home

What [Untitled Goose Game] bought us was just the ability to be as relaxed as possible

Michael McMaster

For the tour's conclusion, we've all gathered at the central mountain's summit, arriving just as the sun peeks over the horizon and bathes the world in pink, syrupy light.

Disseldorp is fiddling with a handheld radio, seeking the perfect station to complete the mood, while the rest of us pass around a pair of binoculars and Strasser describes placing every single rock on the island by hand, working his way around clockwise. He points out the areas already done, with an outstretched arm. "I've gotten to the edge of this valley," he says. "That's my big job, between now and release."

Returning to the party analogy, we get the sense of the team being proud hosts, tidying up the place before they start letting people in. Inevitably, conversation drifts to the last time they released a game. "The comparison between that and Big Walk has been interesting," Strasser says. "And, like, preparing ourselves that it's not going to be the same kind of experience. Because it couldn't possibly be." In what way? "I mean, like, Blink-182 isn't going to talk about it at a weird Discord gig."

Gillespie-Cook steps in: "There's this impossibly high bar that we can never clear again – and maybe that's kind of helpful to us." Untitled Goose Game's success has been invaluable in other ways, McMaster adds. "What that bought us was just the ability to be as relaxed as possible, basically, in making the game. Not needing to worry too much about our budget, or getting the game out by a certain time, anything like that." Hence being able to place individual rocks, presumably.

"We've really only been accountable to ourselves," McMaster concludes. "For us, it's basically just been: can we finish this game before we're sick of working on it?" And, as development approaches its fifth year, how's that going? "I mean, it's been a long time. I thought the feeling would have seeped in by now, but…"

At times, the House House team talk about Big Walk almost as though it's something they've discovered, rather than made. We can understand why, given where it came from – the real Wilsons Prom, the lockdown project that accidentally became something bigger – but we wonder whether it might be a bit of a defensive measure too, allowing them to take a little extra pride in this magical thing.

"It's so cheesy to say, and I feel embarrassed every time I do, but this really is my favourite videogame to play," Gillespie-Cook admits. "I love playing, every time we do it – and we have to play it a lot. Like, that's our job." And yet, the thing Gillespie-Cook has treasured most about this whole experience is getting to watch playtesters, he says: "Seeing the world through someone else's eyes and watching them get it, in the same way that I get it, has been very special. There's this special feeling we talk about all the time – where, six months ago, we all sat down around a desk and said, ‘Oh, and when they come round this corner, they'll have this reaction'. And then getting to watch someone have that reaction, months later, is the sweetest feeling in the world."

Disseldorp's single favourite moment from the development process involves his colleagues spontaneously acting out the opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey in-game: "Going, ‘Ooh, ooh, ooh'." But he agrees with Gillespie-Cook's point. "I already know from watching people play this game that at least some people have really strong emotional reactions to it. That's an unqualified success. That's enough for me. I don't need it to be another Goose Game as well."

The conversation appears to have taken another turn towards the reflective. That seems to keep happening. Perhaps there's something about this place that causes people to open up their hearts, but whatever the case, these past few hours on the island have taught us the laws of what must happen next. Action and reaction.

And so we thank the team for the tour, and for all their thoughtful answers, then run headlong towards the edge of the mountain, and jump. We just about hear the reaction, back up on the summit, before the fall – and the rules of Big Walk's proximity chat – suck the sound away.

Check out the best co-op games to play with your buddies while you wait for Big Walk to get a release date.

Alex is Edge's features editor, with a background writing about film, TV, technology, music, comics and of course videogames, contributing to publications such as PC Gamer, Official PlayStation Magazine and Polygon. In a previous life he was managing editor of Mobile Marketing Magazine. Spelunky and XCOM gave him a taste for permadeath that's still not sated, and he's been known to talk people's ears off about Dishonored, Prey and the general brilliance of Arkane's output. You can probably guess which forthcoming games are his most anticipated.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.