The clue that Steven Spielberg couldn’t be content simply making a film about dinosaurs, that whatever film he created on the subject would have to be an “event” capable of propelling itself off the screen and into the audience, can be found – as with so many things – in the director’s childhood.

In 1960, when Spielberg was a 13-year-old living in Scottsdale, Arizona, the Irwin Allen dinosaur movie The Lost World (“150,000,000 years ago or today?”) came to one of the big cinemas in Phoenix, a half-hour drive from his house. “My friends and I took a lot of white bread and mixed it with milk, Parmesan cheese, creamed corn and peas,” he later recalled. “We put this foul-smelling mixture into bags, went to the movie, and sat in the highest balcony. At the most exciting part, we made vomiting sounds and squeezed the solution over the balcony on the people below. We did it for laughs. Little did we realise that it would begin a chain reaction of throwing up. The movie was stopped, the houselights came on, and ushers appeared with their flashlights – ready to kill us ... We raced out the fire escape exit.”

Jump eight years to 1968, and Spielberg had just signed a contract with Universal, which would see him direct several episodes of television before making the leap to features. One day he was assigned the job of giving a tour of the studio to a young writer who had just sold the rights to his novel, The Andromeda Strain. Michael Crichton and Spielberg got talking. Leap forward another two decades to an autumn day in October 1989, and Spielberg and Crichton – richer, more experienced, and with grey hairs starting to speckle their heads – were sitting in Spielberg’s office in Hollywood, California, discussing changes to a draft script based upon Crichton’s experiences as a medical student in a busy A&E department, which would eventually become ER. During a lapse in the conversation, Spielberg asked Crichton if he was working on anything else at that moment.

“Actually, I’ve just finished something,” Crichton replied. “It’s a thriller about dinosaurs. It’s been submitted to my publishers to proof.”

“I’d love to read it,” Spielberg said, and convinced Crichton to mail over an advance copy. The next day Crichton’s phone rang. It was Spielberg – excited. “There’s going to be a real hot bidding war for this,” Spielberg said. “I’m sure of it.”

As usual, Spielberg’s instincts weren’t wrong. When the film rights for Crichton’s seventeenth novel, Jurassic Park, were put up for sale (a $2 million minimum designed to root out time-wasters) almost every major studio in Hollywood jumped to have a piece of the action. The studios – each with their own chosen director handpicked for the job of bringing Crichton’s vision to life – offered a tantalising glimpse of Jurassic Park adaptations that never were. Warner Brothers, for example, had Tim Burton in mind for a potential helmer; summoning up ghostly spectres of stop-motion dinosaurs and Johnny Depp as a Velociraptor. Fox, meanwhile, wanted Joe Dante, less than a decade removed from Gremlins, while Columbia fancied Superman and Lethal Weapon director Richard Donner for the gig. In the end, Universal outbid all – their eye firmly on Spielberg – and Michael Crichton set about writing the screenplay.

First attempts were poorly received. As with many of Crichton’s novels, much of the book’s thrill came from its almost-believable use of scientific theory to explain away what seemed otherwise implausible. That was fine for a pop-science thriller, but less acceptable when put into the mouths of film characters as exposition in a potential blockbuster. Spielberg had a series of images he wanted to build the film around – dino-pupils contracting in bright light; snorting, prehistoric breath fogging glass windows; giant feet squishing mud – and brought in screenwriter David Koepp to help realise this vision.

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

He also reconfigured the cardboard characters of Crichton’s novel so that the story resembled what Slovenian philosopher and film theorist Slavoj Žižek aptly describes as a “chamber drama about the trauma of fatherhood”. This should come as no surprise. Many of Spielberg’s best films are about fatherhood, populated by lonely children and distant, or altogether absent, patriarchs. In the shooting script, palaeontologist Alan Grant’s story arc – in which the character played by New Zealand actor Sam Neill evolves from disliking children to becoming something of a surrogate father – becomes the heart of the film’s human story.

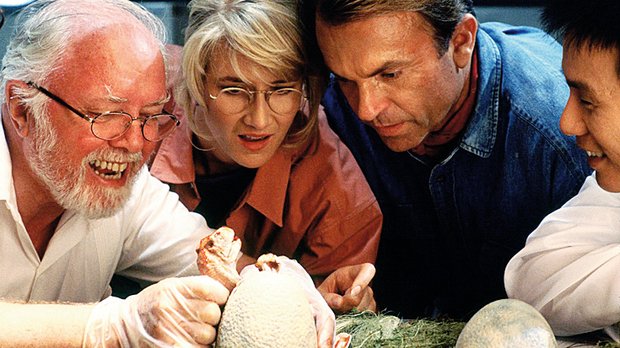

Of course, from the moment the heavy gates swing open and the words “Welcome to Jurassic Park” are spoken, the movie’s main attraction are the dinosaurs themselves – despite their only taking up 15 minutes of the total running time. Of these 15 minutes, nine were created by the Stan Winston Studio in Hollywood. Winston, who passed away in 2008 at the age of 62, was asked to come aboard the film following his work on James Cameron’s Aliens. To Winston, Spielberg gave the job of creating the film’s most memorable dinosaur: the Tyrannosaurus rex.

"Jurassic Park connected fully with the zeitgeist in a way that is rarely seen."

“Steven figured that if we could build a 14-foot-tall Alien Queen, we’d be able to build a 20-foot-tall T-rex,” Winston noted. “That turned out to be a somewhat naive assumption. There was a big difference between building that Alien Queen and building a full-size dinosaur. There were no muscles, no flesh, and there was no real weight to it. The Alien Queen also didn’t have to look like a real, organic animal because it was a fictional character – so there was nothing in real life to compare it to.” This didn’t stop him agreeing to work on Jurassic Park, though. “How are you going to do it?” Spielberg asked early on. “I haven’t got a clue,” Winston replied, “but we’ll figure it out.”

In the end, a one-fifth scale clay model was created, which was then transformed into a puppet by Winston and his associates, while animators at Industrial Light and Magic scanned the model also, and used it to create the film’s groundbreaking digital shots.

Publicity materials for Jurassic Park – 22 years old this year – described it as “An adventure 65 million years in the making”. There might be a hint of truth in this, but it is a mistake to think that any moment during the reign of cinema, before or since, would have seen the film reach the spectacular heights that it did. Jurassic Park connected fully with the zeitgeist in a way that is rarely seen. Part of the reason for this, perhaps, is what the film represented. The Berlin Wall had come down not five years earlier, and what better way to celebrate the triumph of American capitalism than going back to the start of history?

One could argue that with communism gone, dinosaurs were a similar relic of the past over which the United States could triumph. But this forgets the film’s real stars: not Alan Grant and his pals, but the dinos themselves. The genetic tampering which brings them into existence represents the winning combination of science, engineering and commercialisation which boosters would say characterises American capitalism.

That it would somehow grow out of control, become too unwieldy to be constrained any longer, and revenge itself upon its masters by gobbling them up seems startlingly close to social criticism. We know, of course, that this was not beyond the reach of Michael Crichton, for whom thrillers offered a way to explore social issues. Spielberg on the other hand? This crisis of direction concerning the film’s ultimate meaning can be seen most obviously when looking at the character of John Hammond, the wealthy industrialist who opens Jurassic Park. In Crichton’s novel, Hammond is a deeply unpleasant individual, suspected of circumventing the law to carry out his illicit gene tampering. With his unlimited resources but limited ethics and emotional intelligence, Hammond’s “childlike quality” serves as the ultimate example of humanity’s irresponsibility and wanton excess.

For the less cynical Spielberg, on the other hand, a “childlike quality” is exactly the trait that allowed his films to reach the top of the box office. What are Close Encounters Of The Third Kind or ET if not a precocious child’s view of the world and its problems? As the childlike man behind Jurassic Park the film, Spielberg was well aware of what it would mean to criticise the childlike creator of Jurassic Park the amusement park. The desolate shot of Hammond (played by the purposely sympathetic Richard Attenborough) spooning jelly into his mouth as his park implodes is less a moment of realisation about the folly of messing with nature than it is sadness that this likely means the rest of the world won’t be able to join in: like a Hollywood director whose film has failed to open big at the box office, in other words.

Spielberg never had to face up to this problem, of course. Jurassic Park opened with a roar; breaking box office records with the ease of a T-rex crashing through a deactivated electric fence. A survey conducted the year of the film’s release stated that an incredible 98 percent of the US population had heard the name of the film repeated some 25.2 times, while Spielberg agreed to license the film’s logo for an astonishing 1,500 items in a deal worth $28 million.

The director himself ultimately earned more than $250 million from his involvement. In the end, any expectations that the film would serve as a critique of the evils of unchecked capitalism went the way of the dinosaurs...

Click here for more excellent SFX articles. Or maybe you want to take advantage of some great offers on magazine subscriptions? You can find them here.

SFX Magazine is the world's number one sci-fi, fantasy, and horror magazine published by Future PLC. Established in 1995, SFX Magazine prides itself on writing for its fans, welcoming geeks, collectors, and aficionados into its readership for over 25 years. Covering films, TV shows, books, comics, games, merch, and more, SFX Magazine is published every month. If you love it, chances are we do too and you'll find it in SFX.