Is a movie ever complete? In the age of streaming giants, it doesn’t have to be

How streaming services could mean the end of a definitive version of your favourite releases

Leonardo da Vinci, renaissance legend and namesake of a sword-wielding adolescent turtle, once pointed out that, “Art is never finished, only abandoned.” Had the artist and inventor lived 500 years later, however, he may have had cause to rethink his stance.

While his statement about the artistic process has been true for most of human history, these days there’s no need to ever call it quits. Publication no longer has to be a full stop on the creative process in the digital age – in fact, as streaming becomes the dominant form of entertainment consumption, it’s possible to keep tinkering indefinitely. If Leonardo never quite nailed the twinkle in the Mona Lisa’s eye, he could always have fixed it in Photoshop…

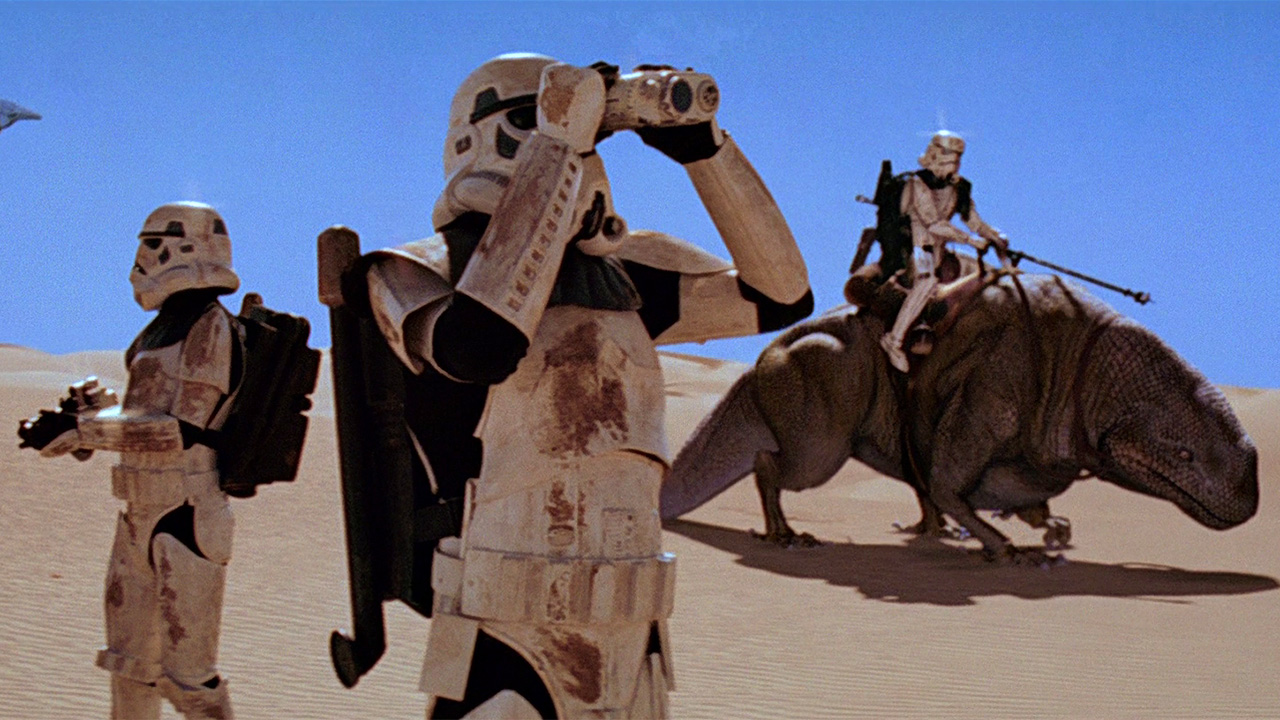

Updating published works is not a new phenomenon. Late editions of newspapers have been responding to breaking stories for decades, while novels are often reprinted with subtle revisions. Movies have also benefited from revised releases. When a director’s cut of Blade Runner hit cinemas in 1992, it ditched the happy ending and Harrison Ford’s disinterested voiceover, and was subsequently hailed as a classic. Meanwhile, George Lucas’s numerous versions of the original Star Wars trilogy – a random CG creature here, a Rodian bounty hunter shooting first there – have become the stuff of legend. And infamy.

Though new edits were historically based around physical releases, however, we’re now in a place where a streaming platform can make lots of tiny edits to a movie or TV show while the viewer is none the wiser – nobody needs to make a fanfare about it because it’s essentially as easy as editing a web page. And because Disney+ and Warner’s HBO Max – and, to a lesser degree, Netflix and Amazon – are generally distributing their own content, they have an unprecedented level of control. Being the rights holder, distributor and shopfront is a real gamechanger.

Ch-ch-ch-changes

It’s a power that can be – and has been – used for good, as we saw when the mass protests that followed the death of George Floyd prompted platforms to subtly excise scenes, or entire episodes, containing racist content. Uploading new versions to a few servers is rather more straightforward than recalling a load of stock from a DVD seller.

And while the resolutely family-friendly Disney Plus has been editing its content since day one – from the removal of Michael Jackson-starring Simpsons episode "Stark Raving Dad", to prudishly covering up a mermaid’s bottom in Splash – they’ve also shown a willingness to respond to viewer feedback. So, after a widescreen conversion of early Simpsons episodes had the unfortunate consequence of removing key visual gags – had they ever seen The Simpsons? – they’ve now restored the 4:3 originals.

Beyond the ability to make speedy amendments, however, this new flexibility does raise the question of whether a movie or TV show can now ever be considered “abandoned”. Downloading regular updates for our computer software, apps, and games has now become a fact of life, so should we start thinking about scripted entertainment the same way? Is it an entity to be constantly, incrementally revised?

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Sounds far-fetched? It’s already happened in music, where Kanye West followed up the original streaming release of his 2016 album The Life of Pablo – “a living, breathing, changing creative expression” – with numerous updates, including remixes and even new tunes. Where the album had once been an indelible snapshot of a point in a recording artist’s career, it was suddenly something more amorphous, and much harder to pin down. Of course, this can be incredibly frustrating if you prefer the original version all along…

An extra something...

There’s an argument to say that, once a popular artistic endeavour is out in the public domain, it belongs as much to the fanbase as it does to the people who made it – emotionally, if not legally. In other words, if you want to buy a remix of your favourite record that’s fine, but you should always have the original to go back to. It’s the reason many Star Wars fans were annoyed when George Lucas deleted the original CG-free, Han-shoots-first versions of the trilogy – they were the films they’d grown up with and loved.

That said, when the Special Editions arrived in 1997, what we were getting was well signposted – information we could be denied if subtle, behind-the-scenes updates were to become the norm on a streaming service. In that situation, it’s surely the responsibility of the platform to tell you what changes they’ve made. Ideally, they’d also give you the opportunity to watch the original version as well – provided, of course, that it doesn’t contain anything offensive.

Even though the tech exists, it’s still unlikely that streaming platforms will start making wholesale changes to old properties as a matter of course – the reported $20 million-plus Warner Bros are pumping into releasing the Justice League Snyder Cut on HBO Max puts the deluxe treatment way out of the league of your average TV show.

But should Justice League 2.0 become the ‘definitive’ version on HBO Max, it does start to raise interesting questions on the nature of canon. The special editions of both Aliens and Terminator 2 have come to be regarded as the definitive versions, with the additional scenes now considered canon. But if content never stops evolving, the sliding block puzzle that is modern franchise continuity could be blown apart. When director James Gunn said he wanted to “George Lucas” dialogue back into the original Guardians of the Galaxy, he was only talking about the tiniest of amendments. But in the precarious balancing act that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe, even the smallest tweaks could manifest as a butterfly effect of contradiction and carnage elsewhere.

And don’t assume that each decision would necessarily be down to artistic endeavour, the result of a filmmaker striving to perfect their vision. Every streaming platform has access to gigabytes of data about their customers’ viewing habits, a wealth of information they can use to inform their every commercial move. A showrunner fixing a line of dialogue is one thing, but what if a streamer decided to re-cut a TV episode because they realised audiences were tuning out during that talky scene in act two?

This may be an overly dystopian, Black Mirror vision of our viewing future, but now that the technology’s there, the streaming giants owe it to the audiences who bankroll them to protect the content they watch. As Uncle Ben Parker – a philosopher every bit Leonardo’s equal – eloquently put it: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Richard is a freelancer journalist and editor, and was once a physicist. Rich is the former editor of SFX Magazine, but has since gone freelance, writing for websites and publications including GamesRadar+, SFX, Total Film, and more. He also co-hosts the podcast, Robby the Robot's Waiting, which is focused on sci-fi and fantasy.