TF Classic: Manhunter

Blood, psychos and dragon tattoos

Blood, psychos and dragon tattoos: Total Film gathers together the key players behind the original and best Hannibal Lecter book adaptation for a butchers at the making of an unnerving ’80s classic…

It’s 1985. James Brown tells us in ‘Living In America’ that the States is still the promised land. Serial killer Richard Ramírez reminds us it’s anything but.

Dubbed ‘The Night Stalker’ by the media, the El Paso-born Ramírez is in the midst of a killing spree, terrorising the residents of Los Angeles.

Husband and wife Vincent and Maxine Zazzara, two of Ramírez’s victims, are found dead at their home.

Maxine, 44 when she died, is left naked and stretched out on her bed, her eyes gouged out and with stab marks across her face, neck, abdomen and groin.

Ramírez was hardly an isolated case. While Ted Bundy was on death row, awaiting the electric chair for at least 30 murders that took place between 1974 and ’78, Jeffrey Dahmer was gearing up for a reign of terror that would see the rape, torture and murder of 17 men and boys.

In this atmosphere of dread came Michael Mann’s Manhunter. Filmed in the autumn of 1985, just as the seminal Mann-produced cop series Miami Vice began to dominate the airwaves, this adaptation of Thomas Harris’ 1981 novel would eventually become known as the first film to bring us Harris’ cultivated cannibal, Dr. Hannibal Lecter.

In truth, Lecter was a mere bit player in Harris’ novel, which details the pursuit of another serial killer, the disfigured Francis Dollarhyde, who has brutally slaughtered two families and earned himself the nickname ‘The Tooth Fairy’ because of the bite marks he leaves on his victims.

Known for his ability to put himself into the minds of killers, FBI profiler Will Graham – who caught Lecter three years earlier – is reluctantly lured out of retirement to lead the investigation.

But when he draws a blank, Graham is forced to face his own demons and petition help from the incarcerated Lecter.

For Mann, Harris’ novel was simply “the best detective story I’d ever read”. Like Harris, he was fascinated in criminal psychopathology.

For years, he’d been corresponding with jailed Californian serial killer Dennis Wayne Wallace, a paranoid schizophrenic obsessed with a woman he had met only briefly.

Having killed three or possibly four to ‘save’ her, Wallace was under the belief that ’60s band Iron Butterfly’s hit ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’ was their song.

Mann would eventually incorporate this into Manhunter, using the track as Graham comes crashing, quite literally, through Dollarhyde’s window in the amped-up finale.

Mann was equally intrigued by Graham’s specific skills in “applied psychology” – his ability to use “physical evidence and sociological and psychological knowledge to fathom the killer’s methods, motivations and character”.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

After being approached by DEG, Dino De Laurentiis’ production company, to adapt Harris’ novel, Mann spent time with the FBI’s behavioural science unit.

“There was one guy there who was in many ways very like Graham, only less jittery, less on the edge,” observes the filmmaker.

“He hadn’t become so involved in his work that he’d cracked up under the mental and emotional strain of identifying with the psychotic, criminal mind. In fact, he was very normal, at least until he started talking about some of the cases he’d worked on.”

Research data in, Mann began to think about casting – in particular Graham. He’d briefly considered the Illinois-born William Petersen to play James Caan’s partner-in-crime in his 1981 film Thief, but eventually went with James Belushi. Then his name came up for Manhunter.

“Of course Dino was like, ‘I need Richard Gere or Mel Gibson.’ Paul Newman, he actually tossed out at one point,” recalls Petersen.

“But Michael said, ‘No!’ He fought for me.” And he had to fight. Petersen’s only major role to date – as the Secret Service agent in William Friedkin’s To Live And Die In L.A. – was still in the edit suite. “It’s quite an interesting period of time, with Billy Friedkin, Michael Mann and me,” says Petersen. “I remember Michael wanted to see some footage of me and Billy not letting him.”

Despite their differences, Mann briefly considered Friedkin for the key role: Dr. Hannibal Lecter (renamed ‘Lecktor’ in the script).

“I’m not sure it ever got to Billy,” says Petersen, “because I’m sure Billy would’ve loved to do it.”

Others in line included John Lithgow, Mandy Patinkin and, crucially, Brian Dennehy, who had featured in Mann’s 1979 prison movie The Jericho Mile.

But rather than snatch at the part, Dennehy told Mann, “I’m going to prove to you what a great friend I am. There’s somebody who’d be better than me for the role.”

It was Brian Cox, an accomplished actor for the Royal Shakespeare Company who was last seen acting opposite Laurence Olivier in a film version of King Lear.

On Dennehy’s advice, Mann went to see the Scottish-born actor on stage in New York in a production of Ron Hutchinson’s play Rat In The Skull.

Cox has his own theory why Mann eventually plumped for him and not the others. “They were all Americans and I was a Brit,” he says. “Anybody that’s too clever has to be a little bit nasty. And therefore has to be played by a European.”

While Cox notes that Bundy et al were making the headlines in the US at the time, he was more influenced by the handiwork of the US-born Scottish serial killer Peter Manuel, who was at large during Cox’s childhood.

“He, for about a year, created mayhem, where he murdered two families and raped several young girls, shot and killed a taxi driver. Manuel was extraordinary because he had no sense of right or wrong. He had a kind of absence.”

As Cox notes, “Evil seems to me something which is absent rather than something which is present. And that’s what struck me about Lecter. He was a very intelligent man but he had completely no moral sense whatsoever.”

Meanwhile, Petersen spent time at Quantico, in Virginia, the home of the FBI Academy – talking to everyone from ballistics experts to profilers working on the Ramírez case.

“I was asking them, ‘How do you survive? You’ve got kids at home. And you’ve just come from a scene where a family’s been slaughtered, tied up and with pieces of them taken away to be eaten later.’ And they just said, ‘We’re men and fortunately we can compartmentalise,’” recalls the actor.

“Of course you don’t really turn it off. They can tell their wives that they can turn it off. But at the end of the day, even if you’re just a regular policeman, it takes a toll.”

According to Mann, Graham is “torn apart by getting too close to the killer’s mind” – proof that Manhunter is less a police procedural than it is a psychological thriller about the disturbing effects such detective work has on the mind.

Arguably, with much of the violence left off screen, this is why Mann offers an impressionistic treatment of the horror of Dollarhyde’s crimes – be it blood-splattered walls or black-and-white stills in Graham’s file.

“I never wanted a movie with explicit violence,” says Mann. “In this case, it would’ve been too tough… also the film is less about the killings themselves than about Graham’s consciousness, his methods of detection.”

The Lecter-Graham confrontation was shot on a studio set over three days, “which is a long time to spend on one scene”, notes Cox. Partly, it was to give the actor room to feel his way into playing Lecter.

“My bias was always to be a little bit more hidden, a little bit more unrevealed… but I played it broader. I played it louder. I played it more forceful. I played it more violent. We just played around with it for three days.” The pristine setting for their tête-à-tête was, as Mann puts it, “white bars against white tiles – so the slightest facial expression is amplified”, emphasising Cox’s chilling, detached turn.

It’s this queasy moment that sends Graham running from the high-security clinic – the exterior, with its seemingly endless spiral walkways causing the detective further agony as he flees, shot at Richard Meier’s High Museum Of Art in Atlanta. Their only other contact comes in the scene where they speak on the phone.

“At that time, there was a Stevie Wonder song, ‘I Just Called To Say I Love You’,” remembers Cox. “And I wanted to start it off by singing this song. Michael thought this was a great idea and we did it. But unfortunately, there were all kinds of rights problems.”

Aside from Petersen and Cox, Mann managed to find other actors very much at the outset of their film careers. Joan Allen was cast as the blind Reba McClane, Dollarhyde’s colleague at the developing lab, where he pores over Super 8 films to select his next victims.

Dennis Farina, who had made his debut in Thief, reunited with Mann to play Graham’s boss Jack Crawford. Stephen Lang, most recently seen as the ball-busting colonel in Avatar, was recruited to play the slimy tabloid reporter who ultimately becomes a Dollarhyde victim. And Kim Greist, fresh from her turn in Brazil, was cast as Graham’s wife, Molly. Still, there was one more piece of the puzzle: Dollarhyde himself…

Tom Noonan remembers coming in for the audition in New York.

“They kept me waiting for a really long time,” the 59-year-old actor recounts, “and they put this young woman with me to read. I started to read the scene where I’m showing the slides… and she seemed really frightened. And as she started to feel frightened, I started to feel this feeling of power. Michael was behind me and I could feel him get up and start to walk around – I could feel him. So as I started to scare her more, he started to get excited and I started to feel like this person.”

By the time Noonan arrived on the Manhunter set, he was obsessed with the role.

“Michael asked me one day, ‘Is there anything we can do to help you do this better?’ I said, ‘Well, it would be great if I didn’t have to see anybody in the cast that is either after me or I’m after until the scene happens.’ Michael sent out a memo to the cast and everyone in the production that no one was to see me – ever. I travelled on different airlines. I stayed in different hotels. They all had to talk to me as Francis. It created this atmosphere where people were frightened of me. I never met Billy [Petersen] until he came through the window.”

While reports had it that Noonan even stalked the other actors while in character, he was also known for sitting in the dark in his trailer.

“Michael would come to my trailer if there was a long set-up and he’d see the lights out and say, ‘Can I come in Francis?’ And he’d come in and sit in the dark with me.”

When the actor emerged from his trailer, he was psyched and ready to play scenes like the one where he tortures Lounds before setting him alight in a wheelchair – one of the film’s standout sequences. “I was really wound up,” says Noonan. “I was doing 50 push-ups between each take, and we were doing take after take after take.”

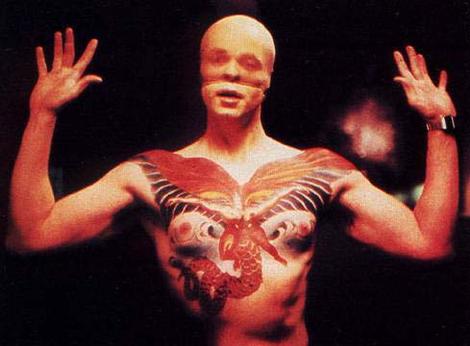

Mann initially filmed Noonan with the elaborate ‘Red Dragon’ tattoo on his chest and back .

Inspired by William Blake’s famous painting ‘The Great Red Dragon And The Woman Clothed With The Sun’, it’s symbolic of Dollarhyde’s ‘Becoming’, in which he arranges his victims in a tableaux to simulate the love and acceptance he has never known, but Noonan recalls the director coming up to him one day and saying, “I think the tattoo trivialises the struggle and we’re not gonna use it.” Cutting the shots of a tattooed Noonan, Mann instead alluded to the Red Dragon – notably with the puddle of blood that forms around Dollarhyde when Graham shoots him dead at the end.

The excising of the tattoo wasn’t the only change along the way. There are two schools of thought on why the title morphed into the more generic Manhunter – though both lay the blame at De Laurentiis’ feet.

“At the time, Bruce Lee was knocking out Dragon movies,” says Petersen, “and Dino, in his wisdom, decided people would think it was a kung-fu movie.” Mann remembers it differently: having just been burnt by the box-office failure of Michael Cimino’s 1985 thriller Year Of The Dragon, De Laurentiis informed him that “he’d have nothing to do with a movie with ‘Dragon’ in the title. So we had to abandon the novel’s original title for something inferior.”

If De Laurentiis was causing problems, even vetoing the mauve-coloured poster due to his superstition that this was “the colour of death”, Mann was pushing his cast and crew to the limit. After a 39-day-and-night shoot, the climactic finale was filmed on the last night, aptly enough on the banks of the Cape Fear river.

According to Mann, the swamp was so “cold, wet and spooky”, half the crew walked, either too frightened or exhausted to carry on.

With the clock ticking, the remainder went down to a local 7-Eleven to buy ketchup and pig’s brains for the shoot-out between Graham and Dollarhyde. “We did the shoot-out in short shots,” says Mann, “so we could throw stuff over the actors and burn cigarette holes in their jackets to simulate bullet holes."

When Manhunter was released in the US in August 1986 (it would take a further two years to hit the UK, due to internal problems at DEG), it was greeted with a critical mauling. Many found fault with Mann’s visually stylish approach and ultra-modernist slant (even the scenes at Graham’s house were filmed at artist Robert Rauschenberg’s beach house).

“The main trouble is Mr. Mann’s taste for overkill,” noted Walter Goodman in The New York Times.

“Attention is diverted away from the story to the odd camera angles, the fancy lighting.” It also didn’t help that Jonathan Demme’s adaptation of Harris’ second novel, The Silence Of The Lambs, would soon relegate Manhunter to a footnote in the evolution of Hannibal Lecter as one of cinema’s most iconic villains.

By the time Anthony Hopkins was mugging his way to an Oscar, Cox was contacted by the Daily Mail.

“The headline went ‘I was the first Hannibal Lecter’ as though it was something I was protesting about. Like I was saying, ‘This was my part. I should be playing it.’ You get actors that do that. It’s bollocks. The only thing I regret is the money. I’m very pleased with what I did and I’m very pleased with the film I’m in.”

Over the years, particularly in the wake of Mann’s subsequent success, Manhunter has been critically re-appraised – and even released on DVD in a Director’s Cut, featuring an ambiguous scene after the final shoot-out in which Graham goes to visit Dollarhyde’s supposed next victims.

“It’s a cult thing now,” says Petersen. “I’ve never talked to anybody that didn’t think it was really good. And I’ve never heard anybody not tell me they didn’t think Brian Cox should’ve been [Lecter].”

Perhaps, then, it’s apt to leave the final words to Cox, who neatly summarises why Manhunter remains the best Harris adaptation. “The whole film was about horror implied, as opposed to horror explained,” he says. “And that’s Michael’s strength.”

TF Classic: Manhunter, Total Film 177, March 2011, pg 112

The Total Film team are made up of the finest minds in all of film journalism. They are: Editor Jane Crowther, Deputy Editor Matt Maytum, Reviews Ed Matthew Leyland, News Editor Jordan Farley, and Online Editor Emily Murray. Expect exclusive news, reviews, features, and more from the team behind the smarter movie magazine.