The Top 7 Wars that would make awesome games

If games ever get tired of recycling the same historical settings, here are a few places we'd like to see them go

4. World War I, so long as it’s anywhere but France

What it was: When we see World War I depicted in movies or games, it’s nearly always the same: the industrial meatgrinder of the Western Front, with troops in gasmasks and doughboy helmets braving machineguns and mortar fire to win a few muddy acres of French hellscape from the guys in the next trench. It’s depressing, it’s futile and it never makes for a great game; the few times it’s been tried, the action’s usually confined to shooting your way through trench tunnels, which gets old fast. (Or it’s been confined to biplanes flying high above the carnage, which works considerably better because it isn’t completely horrifying.)

Above: No gas or barbed wire up here! (From Wings of Honor)

Compare that to South Africa, where British attempts to mobilize the Dutch-descended Boers against Germany resulted in a full-scale rebellion. Or to the German-led guerrilla campaign in East Africa, in which one Col. Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck led endless raids against the British over the course of four years, successfully holding out until Germany itself surrendered. Or to the Middle East, where the British, in an effort to destabilize and distract the Ottoman Empire, sent an officer named T.E. Lawrence to help spark an Arab revolt.

Above: The absence of muddy trenches causes some people to forget that this is actually one of the finest WWI movies ever made

Like World War II, WWI was a massive conflict fought on multiple fronts with millions of possible stories to tell. And like WWII, it seems as though only a handful of those stories ever get told, over and over again. The trenches are all fine and good if you want your mental picture of the war to be as soul-crushing and miserable as possible, but there was a great deal more to World War I than getting caught on barbed wire and choking to death on mustard gas.

Why it’d make an awesome game: Where the mechanized, regimented nature of the Western Front would make it especially inhospitable (and monotonous) for any kind of solo operative, spy or commando, the other theaters of World War I – particularly the African and Middle Eastern ones – were considerably more chaotic, and therefore considerably friendlier to anyone wanting to play conquering badass. Trying to out-guerrilla German commandos in the jungles of Africa (or blow up their naval vessels, like in The African Queen) could play out like a low-tech Snake Eater, and really, who wouldn’t want to lead Bedouin hordes against the Turks as Lawrence of Arabia?

3. The Great Game

What it was: There are wars between nations, there are World Wars, and then there is The Great Game. Also ominously known as the Tournament of Shadows, the Great Game was a long, often indirect conflict that played out for more than a century between Britain and Russia, with Central Asia as the playing field. The rules were simple: limit the other side’s influence and territory by grabbing as much of it as possible yourself.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Above: As seen in this depiction of the 1838 First Anglo-Afghan War, large parts of the Great Game played out in Afghanistan, which is always a fantastic place to invade

Beginning in the early 19th century (or earlier, depending who you ask), Russia and Britain were faced with a problem: Russia wanted to expand, and it wanted to expand in the direction of India, Britain's prize colonial holding. Britain had a pathological fear of losing India at the time, and wanted to do everything in its power to make sure that Russia didn’t take it away from them. The surest way to do this, Britain decided, would be to use Afghanistan – conveniently situated between Russia and India – as a “buffer state” against Russian invasion, something that took two wars to accomplish.

Above: The Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1880, as envisioned in Richard Caton Woodville's Saving the Guns at the Battle of Maiwand

The problem with that approach was that Afghanistan wasn't the only country that shared borders with Russia and India. Persia and China did, too, and Russia seemed dead-set on making inroads into them. It’s probable Russia never actually intended to use any of those inroads invade India, but it seemed to enjoy driving Britain nuts with the possibility (and of course, there were plenty of other reasons to start grabbing territory in Central Asia, control over the opium trade being a popular one at the time). So began what was essentially a long game of Risk for control of Central Asia, with each power continually inching into new areas, only to have the other attempt to head it off at the pass.

As the Game progressed, Persia, Tibet, Mongolia and China all became key playing fields for the two empires. Invasions, colonial wars, rebellions and backdoor diplomacy became increasingly frequent, and vast intelligence networks reportedly sprang up to help each side monitor and undermine the other. Things came to a head with the 1853 outbreak of the Crimean War, which threw the two sides into direct conflict as Russia attempted to conquer assorted Central Asian and Eastern European chunks of the Ottoman Empire. It wasn’t until the years preceding World War I, however, that the Great Game was finally set aside, as Britain and Russia joined forces against Germany and its allies – only to resume the Game soon after, ending it only after Britain had finally abandoned its imperial aspirations following World War II.

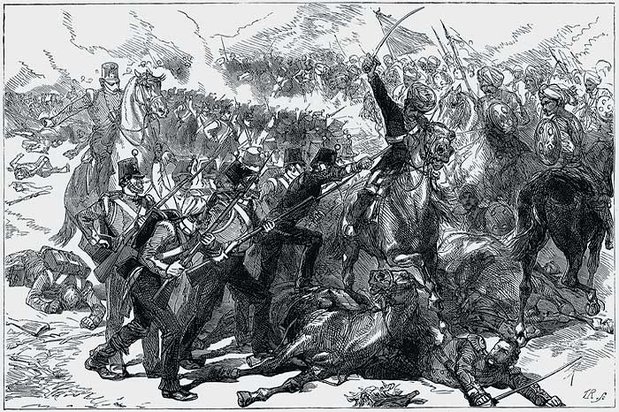

Above: The Charge of the Light Brigade, also by Woodville, depicts one of the more tragic events of the Crimean War (just before it turns really tragic, obviously)

Why it’d make an awesome game: It’s called “The Great Game!” It’s right there in the title! Even ignoring the obvious strategy-game possibilities, though, there’s a lot of meat in the idea of Russian and British secret agents trying to outmaneuver the authorities and each other against the backdrop of the Victorian era, the British Raj, the Anglo-Afghan wars and the Chinese Opium Wars. It’s largely an unexplored area for games, but that’s part of what makes it so interesting – the potential for Victorian-era pulp adventure is huge, so long as someone’s willing to take that first step to re-create it.