Fatal Frame's iconic camera exists to force players to "look straight at something scary" says series creator: "We thought it would really bring out the scariness of the ghosts"

Feature | Fatal Frame series creator Makoto Shibata and producer Keisuke Kikuchi on how they delivered a trilogy of the scariest horror games ever made on PS2

The best horror games tend to show their cards differently to horror films. Where in films things often begin harmoniously, with just some eerie music or a mildly unusual sighting hinting at the impending darkness, videogames like to come out swinging. Think of the chaotic lorry-crash opening of Resident Evil 2, the alley nightmare that introduces you to Silent Hill or, going back, the monster smashing through the window in Alone In The Dark.

In some ways, the 2001 PS2 horror game Fatal Frame ('Zero' in Japan, Project Zero in the EU) sticks to the fundamentals of the great games leading up to it. The difference is that nothing really happens for a good while in Fatal Frame.

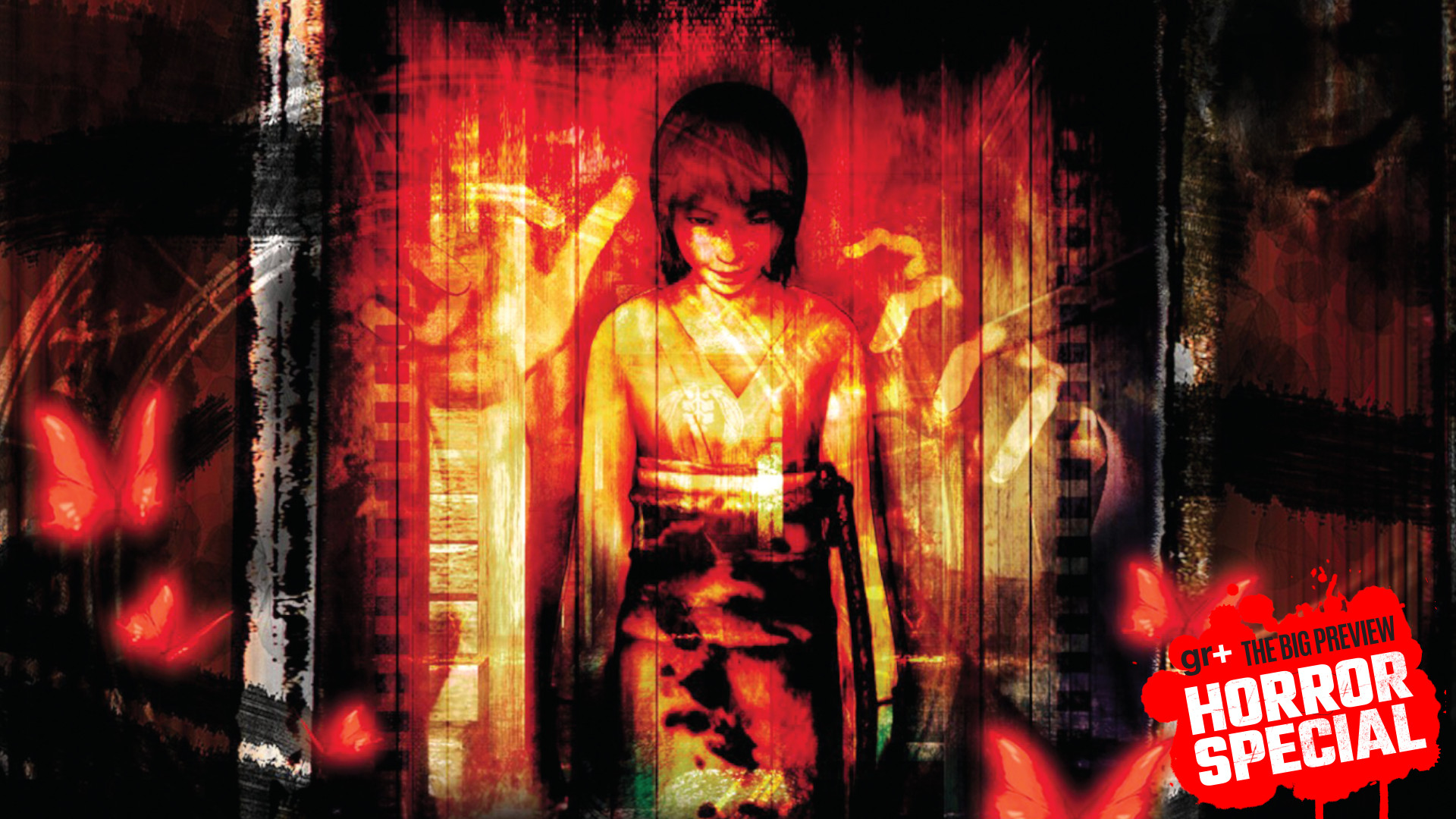

The Big Preview Horror Special hub has even more exclusive access to the biggest games in the genre on the horizon, and deep dives into iconic classics!

Instead, after a nebulous opening cutscene introducing the sixth‑sensed siblings Miku and Mafuyu, you enter the Himuro Mansion and are instantly submerged in a murky lake of reverberating sound – choral wailing and cavernous synths that sound both incorporeal and all-enveloping. Resembling the micropolyphony used in movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey and the excellent 2015 horror The Witch, it's an unyielding alarm from a dark dimension; it tells you that you're now in a tortured place, and there's no turning back.

A thousand tasteful touches like this helped Fatal Frame build on the fine lineage of survival horror games dating back to the original Resident Evil in 1996. It inherited certain traits of its predecessors – semi-fixed camera angles, stodgy movement and a scarcity of resources – but also addressed many oversights and shortcomings that had been blighting the genre for years.

The most glaring of these was the fact that, despite all the best horror games around the turn of the millennium being Japanese-developed and driven by Japanese art styles and design philosophy, they leaned heavily on western horror movies: Resident Evil and George Romero zombie films, Clock Tower and Dario Argento slasher flicks, Silent Hill 2 and Jacob's Ladder. It didn't matter that Japan had its own rich horror legacy – there seemed to be no belief among publishers that a wider audience would be interested.

Fatal Frame creator Makoto Shibata didn't want to simply recreate western horror through a Japanese lens. The rise of Japanese 'J-horror' in the west, courtesy of breakthrough hits Ringu and Ju-On: The Grudge – whose American remakes were released evenly between the first three Fatal Frame games – proved that the world was captivated by these distinctly Japanese tales of curses, vengeful spirits and rituals.

But when talking to us about the inspirations for Fatal Frame, Shibata only alludes briefly to the growing popularity of J-horror – that was more a concern for publishers. Instead, he focuses on the traditions of Japanese horror and his own ghostly encounters.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This feature originally appeared in Retro Gamer magazine 216. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Retro Gamer or buy an issue!

"This game started with the idea of creating a horror game where the scariest thing possible is the enemy. For me, what I feared most were ghosts, much more than monsters," he tells us. "And while we considered various weapons to use to fight those enemies, we found that a camera was the best fit with the gameplay. You need to look straight at something scary, and then draw it in as close as possible in order to photograph it, so we thought it would really bring out the scariness of the ghosts."

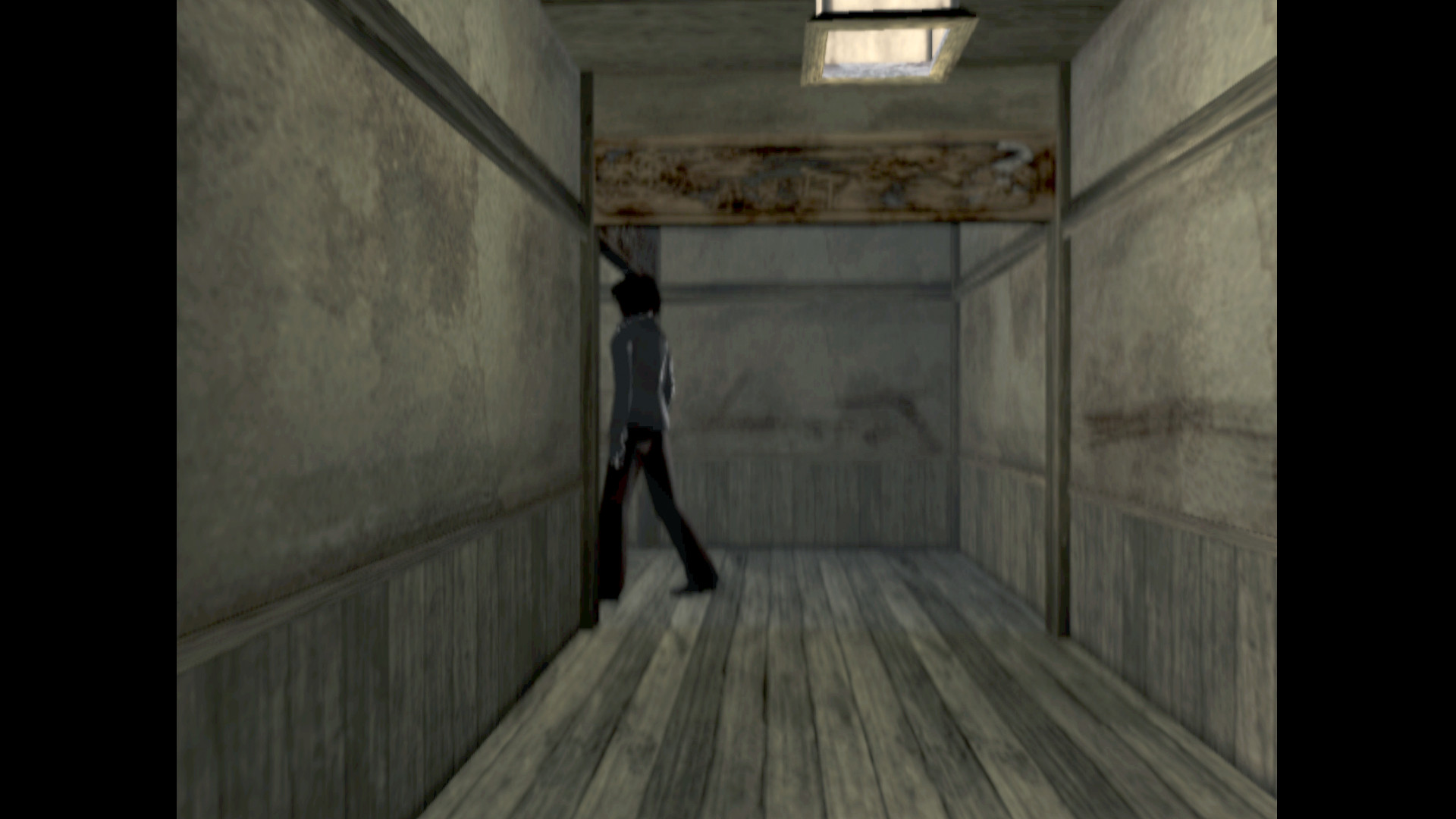

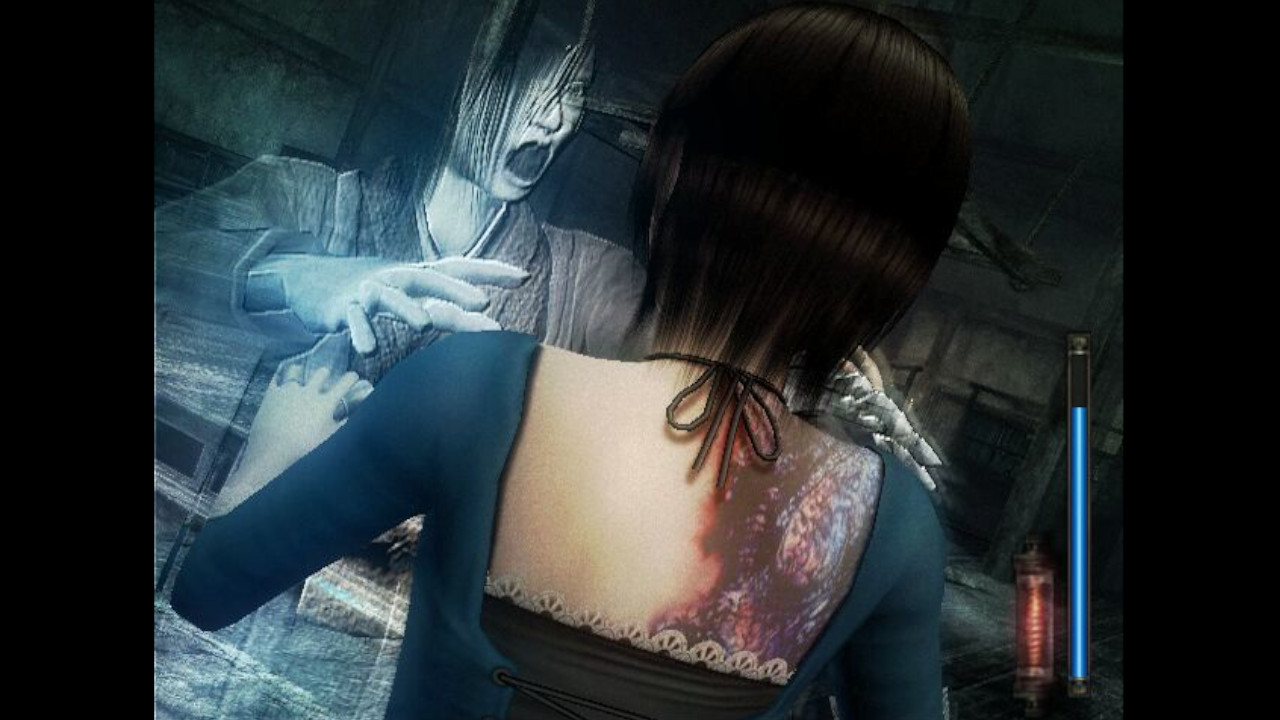

The series' mysterious camera, the Camera Obscura, worked on multiple levels. Firstly, it pulled us into the first-person perspective, which few horror games had done up to that point. Suddenly, you weren't just navigating a person around foreboding environments – you were that person, fully immersed in these places that were fully 3D-rendered rather than prerendered like many horrors before it.

Aim down sights

In some ways, this camera-eye view was liberating, letting you freely move around environments to spot items and ghostly sightings that would not be visible in the main 'field' view. But looking and moving in this perspective were agonisingly slow, like a nightmare where you're trudging through mud to escape a monster. First-person exploration felt claustrophobic too, with the ornate frame around the camera lens restricting your field of view. The perspective made puzzles more interesting as you scoured the environment for clues, while pulling you into a prescient style of horror to evoke what Shibata and producer Keisuke Kikuchi call "an incomparable sense of isolation".

Meanwhile, the field view fully exploited the horror potential of increasingly unfashionable semi-fixed cameras. Low‑angle shots with Miku in the distance meant spectral beings could glide by in front of the lens to the jarring screech of violins, or something could disappear around a corner at the end of a long corridor. Everything about Fatal Frame was intense, and just 15 minutes spent in this mire of dark soundscape, jump scares and more subtle spooks would leave your nerves shredded; before long, you were mistaking grainy shadows or tattered curtains for ghosts, and questioning whether markings on the wall resembled scratch marks or human outlines.

One day, I thought up a way to 'see them without looking at them' – by using a broken camera I received from my father.

The 'based on a true story' suffix to the game's name isn't quite as absurd as it sounds. Shibata's entire life – from childhood to the development of the Fatal Frame series – is shaped by paranormal events. In fact, one of his earliest memories of these is how he came up with the idea for the Camera Obscura.

"When I was young and would wake up in the middle of the night, I frequently heard the whispering of large groups of people coming from the nearby shrine and passing in front of my house. It was a time when I didn't know the term 'ghosts' but even as a child I knew that this was something I must never be involved with. I believed that if I opened the curtains and saw that process, I would be taken away by them.

"One day, I thought up a way to 'see them without looking at them' – by using a broken camera I received from my father," Shibata continues. "If I looked at them through the viewfinder of the camera, I could see them without them knowing. It was a very childlike idea."

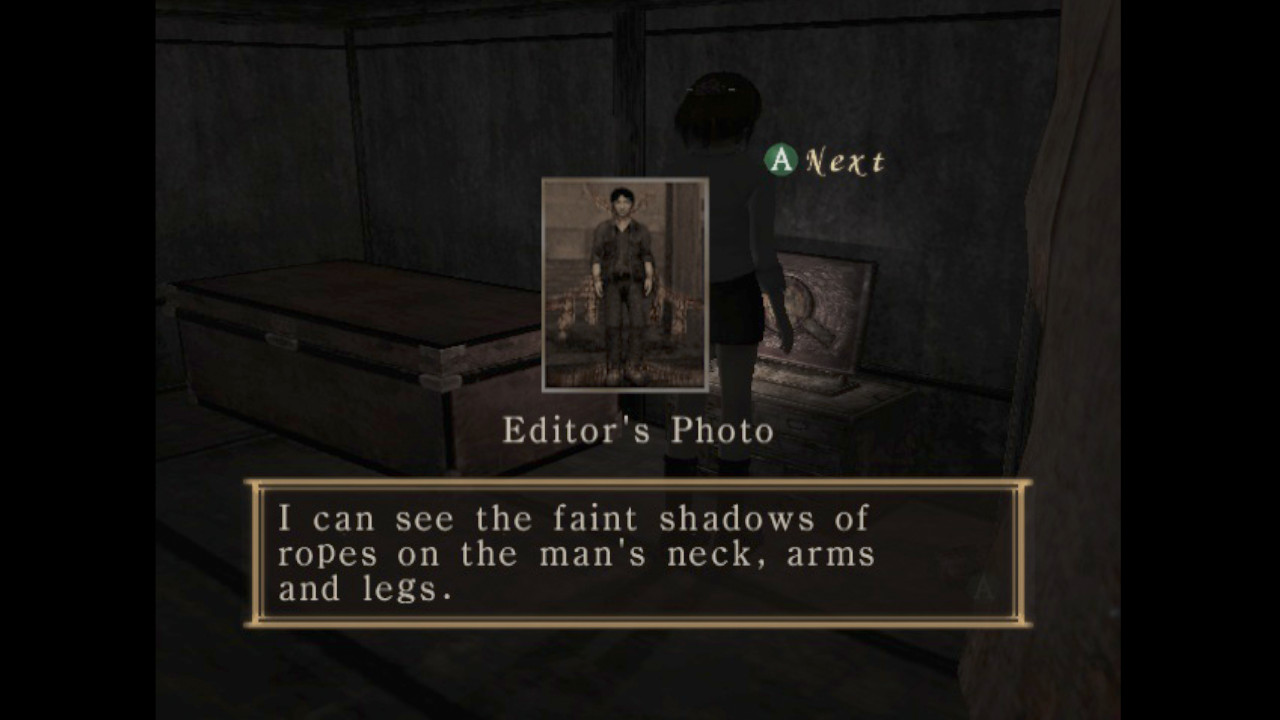

Cameras have their own history of dalliances with the paranormal. There was the practice of 'spirit photography' in the 19th century, when cameras could ostensibly capture the spirits of the dead in photos with their living loved ones. This was actually a double exposure trick, but several snake-oil photographers made good money off this practice before being exposed as hoaxsters.

There are also lingering beliefs among the older generations in Japan around the dark nature of photography. One superstition has it that three people shouldn't take a photo side by side, because it will condemn the middle person to an earlier grave than the other two (with the pragmatic knock-on effect that older people would usually be given the central position in photos – making the curse align conveniently with nature's course).

Another old belief indigenous to Japan is that photographs could steal a person's soul – the more accurate the picture, the more soul it absorbs. This is directly represented in Fatal Frame where clearer pictures deal more damage to the ghosts you fight.

Other ideas for weaponry were thrown around, such as using 'ofuda' talismans to ward off the ghosts, or 'Hamaya' ('demon‑breaking') arrows. "At one point, we also rewrote it to employ a game system where you would accumulate fear and use a shout button to shout at a ghost and temporarily drive it back," Shibata said in an interview for the game's website. "It was awful, though." The camera was the clear winner as the weapon of choice – an iconic decision that would become the series trademark, distancing Fatal Frame from the physicality and gore that many of its peers resorted to.

The shortcomings of combat in great series like Resident Evil and Silent Hill were well-known by 2001. Limited moves, and the fact that many players would choose to zigzag around enemies rather than confront them seemed incongruous with the genre (a point highlighted by Silent Hill: Shattered Memories designer Sam Barlow in issue 214).

Fatal Frame, on the other hand, forced confrontation, usually locking you into a room with a ghost that you'd need to track, focus on it to build up the damage you deal, and then let it get as close as possible with the aim of snapping it in a high‑damage 'Fatal Frame' shot.

These fights were intense, but also offered a break from the accruing dread caused by the game's suffocating atmosphere. By popping up scores that showed the damage you dealt, the developers injected a touch of the lightgun arcade experience into Fatal Frame – a welcome bit of 'gaminess' in an otherwise relentless horror experience.

The series heavily revolves around femininity, and the oft-tragic role of women in Japanese folklore and horror myths. "In traditional and classic Japanese ghost stories, it was often said that those who were oppressed and held strong grudges would reappear as powerful ghosts," reveal Shibata and Kikuchi. "In those ancient times, it was often women who were the most oppressed members of society and would reappear as ghosts."

Regular haunts

The types of ghosts you encounter across the whole series echo those of Japanese folklore. There are the Onryou – vengeful spirits lashing out in eternity at the living over the cruel nature of their demise. Those harmless but no less terrifying ones that stalk the corridors and appear when your camera starts glowing? Those are Fuyuurei, or floating spirits – echoes of the dead.

There are also a fair few Zashiki-warashi wandering around the Himuro Mansion – child-ghosts that sing eerie lullabies on the soundtrack, run away from you, and occasionally rise out of floors or old wells to attack you. You know a game takes its spooks seriously when even an infant can be deadly.

Although you strongly sympathise with the boss, you must defeat her.

Being made in the early Noughties, it would be easy to reduce the series' penchant for young female protagonists to a means of heightening the player's sense of vulnerability, but the reality was a little more subtle. In keeping with the myths, the series features female Onryou as its main antagonists. In the first game, this spirit is Kirie, a young woman who was sacrificed in a ritual intended to keep the gates of hell shut. The ritual failed, causing demons to spill out and kill everyone in the mansion, trapping them there as murderous ghosts. The lack of physical combat and desired parallels between the antagonist and protagonist made it a no-brainer that Fatal Frame's hero should be a woman.

"The protagonist's circumstances and feelings have similarities to the final boss. The game's story is one where you must understand the final boss, and although you strongly sympathise with the boss, you must defeat her," Shibata and Kikuchi tell us. "So for that reason, we made the protagonist a female who has a strong ability to sense the supernatural and can sympathise with spirits as well."

Fatal Frame was a success both in Japan and in the west, riding the tide of Japanese horror arriving on western TV screens via the easily distributable medium of DVD. Tecmo wasted no time in commissioning a sequel.

According to Shibata and Kikuchi, many people didn't complete the original because it was too scary. Instead of treating this as a hint to dial down the horror, they instead offered a greater incentive for players to push through their fears. "We shifted our attention to making the storyline more interesting, to encourage such players to overcome the scariness in wanting to see the end of the story."

Fatal Frame 2: Crimson Butterfly was no less menacing than its predecessor, expanding the setting out from a single building to an entire abandoned village – where each house and shrine had its own tragic self-contained stories to tell.

This time you controlled Mio Amakura, who follows her twin sister Mayu deep into the haunted Lost Village, slowly unearthing a brutal story of another ancient ritual – this time involving twin girls. You were no longer just trying to prevent grim history from repeating itself; you and your sister were integral to the malevolent ghosts' plans – the stakes were much higher.

The sequel looked better visually, benefitting not only from the developers having a better grasp of the PS2's technical capabilities, but also from their desire to imbue the game with more beauty, according to the CG director Daisuke Inari, who said in an official blog post: "Since it's a horror game, by its very nature it of course has to be scary. But just being scary doesn't mean just anything will do – ideally, you would be able to feel a subtle Japanese beauty amidst the fear."

To that end, Fatal Frame 2 had a more fantastical feel: a dark twist on Lewis Carroll's Alice In Wonderland where, in place of a rabbit, you followed a trail of ethereal crimson butterflies that broke up the darkness, all the while luring you deeper into it. Many of the houses and other spaces would be mysteriously well‑lit, contrasting with a damp atmosphere in outside areas that evolved on that of the first game. "We put fog across the whole screen to give it a subtle sense of depth," wrote Inari. "Then we worked to make it so that you would get this gradual feeling of unpleasantness, augmenting the strength of the dither and contrast pixel by pixel. The effect also changes depending on whether you're looking through the viewfinder or not."

The presence of your sister, meanwhile, and the non-hostile spirit of a man who helped you navigate the village, provided some human comforts in a vast space that could otherwise have felt too daunting.

But even these elements ramped up the horror in their own way. "The scariest part is the moment when you lose sight of the person you wanted to protect, a person who was like your other half and someone you would give your life in order to save," Shibata and Kikuchi explain. "If there are two characters to begin with, the moment you are alone you become worried. When that important person eventually starts to talk about things you don't know, and when you realise you are re-enacting rituals that the twins had done in the past, it's a frightening moment."

Despite the sense of duty the player would feel towards Mayu, she wasn't designed to die easily, because Shibata and Kikuchi knew that this could build up ill will towards her (note that this was before the infamously fragile Ashley Graham stunk out a good portion of Resident Evil 4 by keeling over dead each time an enemy brushed her shoulder). "We did have concerns that it would become difficult, but also that there would be an allure to having scary scenes where Mayu is attacked and you could save her by capturing the attacking ghosts through the camera," Shibata and Kikuchi explain. "But if Mayu is caught by spirits and dies all the time, players would have negative feelings towards her, so we adjusted the game so that she doesn't die easily."

Snap attack

The Camera Obscura's powers were bolstered. You could now execute combo shots that let you follow up perfectly timed Shutter Chances with second and third shots. Along with the fact that you would often be fighting more than one enemy at once, it gave the combat more of an action flavour.

All the little improvements in Fatal Frame 2 clicked. It became the best-rated and best-selling title in the series, going on to shift 160,000 copies. As with the original game, Tecmo also created an expanded Xbox release, which featured numerous extras, including a brand-new first-person mode and the addition of Dolby Digital amongst other enhancements. Shibata and Kikuchi's sequel firmly established the series as a survival horror heavyweight among fans and critics, even though it came at a time when the genre was waning commercially.

Where Fatal Frame 2 swept the player off into the realm of magical horror, its follow-up (which didn't receive an Xbox port) brought everything ruthlessly back to reality. Japanese horror cinema showed that curses and spirits could just as easily exist in a mundane domestic setting as a cobwebs-and-grandfather‑clocks 'haunted' one. It was time for the series to quite literally bring horror home.

Fatal Frame 3 allows you to experience a more raw, moist kind of fear.

Enhancing its harsh sense of verisimilitude, Fatal Frame 3 also blurred supernatural elements with the very real psychological pains of trauma and grief. Its three protagonists – Rei, Miku (returning from the first game) and Kei (the series' first male protagonist) were all battling with their own personal tragedies. The game oscillates deliriously between the Manor Of Sleep dream world and Rei's home – which slowly starts being encroached upon by the dream realm. Kikuchi summed it up perfectly in the build-up to the game's launch: "The story of the previous game implemented a kind of fantastical scariness, but Fatal Frame 3 allows you to experience a more raw, moist kind of fear."

The Manor Of Sleep, while visited through dreams, was less a dream and more a purgatory dimension, where the living would be haunted by dead loved ones they couldn't let go of. "If it was a dream that only Rei herself sees, then that would just be an odd dream," Shibata and Kikuchi tell us. "But if several people had dreams set in the same house, then we thought that it would feel like the Manor Of Sleep actually exists. That's why we have three people visiting the Manor Of Sleep from different viewpoints."

Switching between three characters in two separate dimensions makes for a sometimes confusing experience, not unlike a dream where the identities of people and places are constantly shifting. In fact, large parts of the Manor Of Sleep revisit locations from Himuro Mansion and the Lost Village – manifesting Miku and Kei's grief – while the rest of it is layered with the sad memories of past visitors.

Each character has their own abilities that let you experience the Manor in different ways. Rei's Flash ability drives ghosts back, while Miku uses her Sacred Stone to slow down time. In an interesting reiteration of the idea that physicality counts for nothing in this series, male protagonist Kei has the weakest camera, and relies heavily on a dedicated 'Hide' button to help him elude passing ghosts.

But for all the Manor's surreal layering and symbolism of each character's trauma, Shibata and Kikuchi believe there's a strange 'comfortable darkness' about the Manor Of Sleep. "There is a classic horror film directed by Robert Wise called The Haunting. In it, after the female lead goes through various experiences in a haunted house, it goes from being a scary space to a comfortable, dreamlike space where she feels at ease," they tell us. The darkness, after all, offers you some solace by letting you hide in it, and the setting would have been at least somewhat familiar to series fans (who, based on the returning characters, locations and myriad callbacks to earlier games, were very much the target audience).

The real horror resides in Rei's house – a sad domestic space where your only comforts are a cat and the cosy sanctuary of Miku's room. You don't directly fight or confront the ghosts in your house, making their presence far more subtle and creepy – slender feet poking out from behind a wardrobe, something gliding past a kitchen curtain that may or may not have been the curtain itself, or that awful bathroom mirror that threatens to spook you throughout the entire game.

To a Japanese audience, the horror of Rei's home would have been in how it encroached on the safe and familiar setting of an urban home. But to a western audience, the sliding paper doors, the shrine to a dead relative, and the grey tones of the home would have felt decidedly foreign, identifiable mostly from what we'd seen in J-horror films. Suffice to say that later in the game when the TV turns itself on and its static begins to crackle, many of us half-expected a long‑haired girl with hair covering her face to clamber out of it.

This was the most uneven but ambitious game in the series. It understood the horror potential of the domestic setting, exploiting it better than possibly any game before or since, including its peer Silent Hill 4, which came out the year before in 2004. Like Silent Hill, the popularity of Fatal Frame was stifled by changing commercial tastes in horror, which shunned psychological horror for more action-oriented fare. The series struggled to move with the times with its later outings, and always seemed more comfortable within the limitations of earlier console generations.

But maybe the series didn't really need to adapt to industry trends, because the things that still make Fatal Frame harrowing today are also traits that make it a game of its time – the artfully placed camera angles, the painfully slow first‑person movement, the careful exploration of beautifully crafted environments that only subtly directed you towards the critical path.

Like the ghosts of its cursed settings, the Fatal Frame trilogy is bound to a certain time and place in gaming history, alluring horror fans with a power to frighten that remains as forceful as ever.

Still hungry for more scares? Check out our best Japanese horror games list for what to play next!

Rob is a freelance games journalist, SEO and content manager. He's written for PC Gamer, GamesRadar, Kotaku, Rock Paper Shotgun, WhatCulture, NextPit, PCGamesN, VG247, Eurogamer, TechRadar, and more.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.