Death Stranding 2 hands-on: An emphasis on combat and vehicles feels like an evolution of Metal Gear Solid 5, while continuing to push the first game's in-depth hiking physicality

Hands-on | Exploring Hideo Kojima's new perspective as he prepares delivery of Death Stranding 2: On the Beach

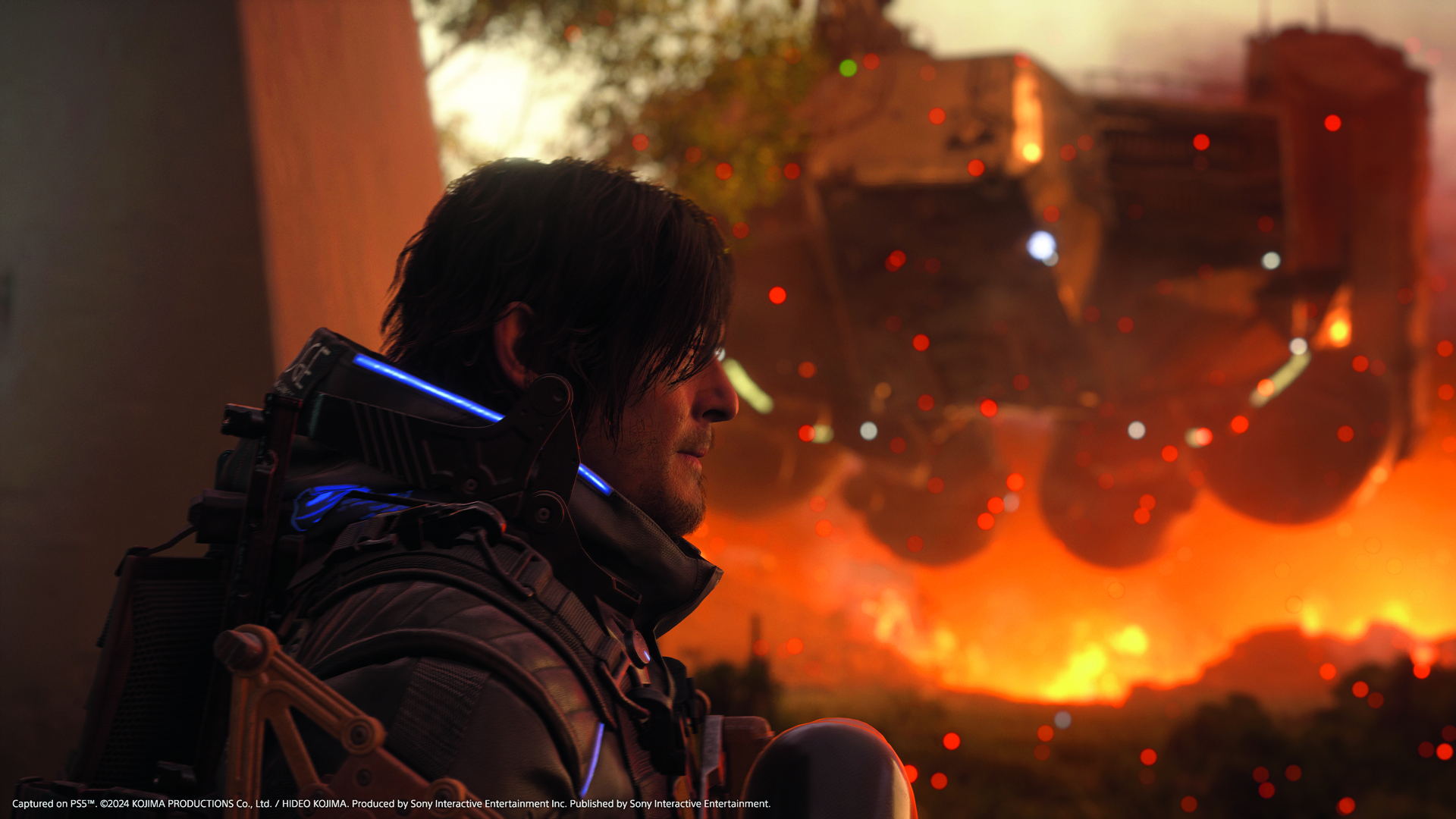

When Death Stranding arrived in November 2019, several months before the COVID-19 pandemic upended our lives and outlooks, it was widely considered the strangest mainstream videogame we'd ever seen. The first project by Hideo Kojima following a messy divorce from Konami, the company at which he made his name, the game defied convention or easy summary. Its protagonist, portrayed by The Walking Dead's Norman Reedus, was a courier named Sam Porter Bridges, and the game mainly involved trudging across desolate, ankle-spraining terrain with an infant strapped to his chest, while burdened with luggage and chased by ghosts.

Looking back at the game, Kojima concedes that it was "weird". One of Bridges' first tasks was, remember, to hoist the US President's cadaver on his back, on a cross-country dash to a local incinerator. But beneath the eccentricity there was also something vaguely humorous about its central challenge: to carry heavy cargo upon your back across North America without tripping. The taller the load, the greater the chance you'd topple. It's the kind of idea you might expect to find in the work of an indie darling such as Bennett Foddy. And yet, with Sony's keen backing, and Kojima's attention-grasping reputation, a game founded on an indie-esque fancy was rendered as an extravagant epic, one featuring celebrities scanned into the game in screamingly high definition, plus a wistful, expensive soundtrack and a story whose looming relevance nobody foresaw.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth features and interviews diving deep into the gaming industry delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

Set in a fragmented America, Death Stranding portrayed a world in which society had collapsed into isolated pockets, connected only by the delivery people who hauled essentials between them. Porters such as Bridges were the new lifeblood of civilisation – not soldiers, not scientists, but logistics workers. At launch, reactions were divided. Some praised the game as visionary, a slow and meditative counterpoint to the combat-heavy overfamiliarity of big-budget games; others derided it as self-indulgent and odd. And then, shortly after its release, everyone entered a world of quarantine, masks and contactless delivery. We were cut off from our friends and family members. Toilet roll became scarce. Death Stranding's vision of human connection maintained through screens and packages suddenly felt less like speculative fiction and more like an act of prophecy.

Developer: Kojima Productions

Publisher: Sony

Platform(s): PS5

Release date: June 26, 2025

Kojima had already written the script for a sequel. Then, during the pandemic, he fell severely ill. He won't discuss the specifics, but it was serious enough to trigger in him something of an existential crisis, a renewed eagerness to make the kinds of games "that don't already exist in the world", ones with resonant messages. When he recovered, he found himself back in his studio's cavernous office, but almost completely alone. "Everyone else was working remotely," he says. "I felt that perhaps I would never meet anyone again."

He watched as the world shifted to online meetings: "We were having drinking parties and school events, but now entirely online, an almost entirely digital existence." It felt exactly like the chiral network, Death Stranding's version of the Internet, which protagonist Sam Bridges was tasked with bringing online, city by city. And yet, rather than feeling the satisfaction of a proven prophet, Kojima felt only dismay. "Something had been lost," he says. "Physically, we weren't connected any more. Nobody could travel. Humans can't be fully human if they can't travel any more." Yes, Zoom and all the other tools had ostensibly brought us together. But online connection, Kojima realised, was not the catch-all cure that his game had suggested to the global epidemic of isolation and loneliness.

The pandemic passed, but the fragmentation and yearning for reconnection? Those remained. Kojima tore up the story he had written for Death Stranding 2. The sequel, he decided, would instead be a cautionary tale about the risks of relying upon digital connectedness in lieu of physical presence. 'Should we have connected?' became Death Stranding 2's motivating question.

It's a message Kojima relays to a group of about 30 journalists from around the world on the first morning of a four-day preview event (or "boot camp", as it's referred to on several occasions by staff members) at his studio's luxurious HQ in Tokyo's Shinagawa district. It's here he spent the lockdown period alone, fretting. Today, an entire wall of the office contains the signatures and messages of notable visitors to the studio. The names include Hollywood heavyweights such as Timothée Chalamet and Nicholas Cage. Some dismiss Kojima as a star collector, but there's something else going on here. Having spent the COVID lockdown isolated in this place, it's understandable that he'd want everyone who visits to leave a reassuring reminder of their presence.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Nobody really does these kinds of events any more.

"Nobody really does these kinds of events any more," Kojima says over a microphone in the studio's pristine white canteen, styled after the set designs of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. And it's true: in-person, group press trips, once a weekly occurrence for magazines such as this one, have fallen from fashion in the digital age. It's not difficult to see why. When preview code can be delivered anywhere in the world in no time at all, to get so many people to travel halfway the world to sit in a room in order to play a videogame might seem needlessly costly, across several metrics. But the physicality is the point, Kojima says, smiling. "I wanted to bring you all here, to be in the room together, talking, with the chance to make friends with a stranger." Nobody could accuse videogames' best-known director of failing to fully commit to the bit.

And yet the shift of focus, and of underlying message, is not immediately clear in what we have all come to play. Death Stranding 2: On The Beach begins 11 months after its predecessor concluded. We find Bridges in hiding, a prickly recluse, shut off from the country he had previously united. In another eerily resonant plot point, he has been made redundant by the Automated Porter Assistance System, an AI-based program that initially provided support for porters but soon took over the business of logistics, making their jobs obsolete. He now lives in what looks like a kind of futuristic shipping container, a building that blends with its surroundings via holographic technology, spending his time raising Lou, the infant that, at the end of the original game, he freed from its artificial womb and welcomed into the world to raise as his own child.

The wind-worn off-road courier and the bonny 18-month-old make an unlikely couple, but, considering the trials they have endured together, their bond is understandable. It's certainly interesting from a gameplay perspective. In the opening moments of Death Stranding 2 you explore the sharp, rusty rocks around your home, keeping your balance as you lunge from outcrop to outcrop, protecting the child strapped to your chest all the while. The sense of delicate stewardship will be familiar to any parent who's navigated the outside world with a baby in tow, and the extreme setting here only compounds a sense of fretful parental responsibility.

When, midway through your trek, the area is hit by a minor earthquake, Lou begins to wail. There is a command dedicated to soothing your child, lifting the baby aloft with a cluck and a bounce – an interaction that is familiar in life, but rare in videogames, of the sort that Kojima has always been inspired to include in his work. "Let's go home and get you fed," Bridges says, when the tremors settle. We now see him in his newfound embrace of hermetic domesticity, cooking food, tidying toys, stockpiling nappies and putting Lou to bed. But he has not entirely let go of his old life. This is, we see, a man who keeps a pistol in his cutlery drawer, just in case.

Death Stranding 2 begins in earnest when Bridges receives an unexpected visit from Fragile, the enigmatic courier played by Léa Seydoux. She now runs a private delivery service, Drawbridge, one of many powerful private contractors that run North America. She gives Bridges a new mission: to connect Mexico, settlement by settlement, to the chiral grid. In a universe filled with arcane terminology and concepts, it's a pleasingly accessible premise: no matter where in the world you live, it's easy to understand the idea of connecting remote settlements to the Internet. Fragile offers to care for Lou as you head out, and Bridges accepts the mission with surprisingly little resistance. We're back in the old boots, hiking and lunging between settlements in Mexico, and dialling in for family check-ins with Fragile and the baby, like a businessman away on a work trip.

Rural Mexico is, however, hardly a welcoming environment. The expanse of territory is marked by plunging ravines and thickly forested mountains; bandits roam its landscapes searching for porters like you, who they can attack and loot. The weather is more extreme than before: punishing sandstorms can roar in without notice, reducing visibility and violently pushing you sideways. Earthquakes cause landslides. Headwinds slow your progress to a crawl, while tailwinds risk causing you to stumble over rocks. Rain is a dangerous substance that ages the skin of anyone it touches, and when it falls it immediately begins to damage your cargo and can quickly raise the waterline in the local rivers, reducing the number of places where it's safe to cross. But while the world is brutal and punishing, it is also littered with valuables, all of which tempt you to make brisk diversions to add them to your teetering backpack and increase the potential rewards you'll receive at the next outpost or settlement.

Every sojourn requires careful planning: is there enough life left in your boots to make the next journey? Will there be BTs – those spectral monsters, drawn to noise, that will claw Bridges down into a tar-like ooze if they catch him – for which you'll need specialist weapons and grenades? If rain is predicted, should you pack a spray that can restore your cargo? Will you take the necessary materials to build, say, a lookout tower, from which you'll be able to locate and track enemies? Every decision has a physical cost, measured in bulk and weight. Overprepare and you risk becoming encumbered, and it usually pays to leave some spare kilograms for treasure you might find along the way.

Most of this feels familiar. You soon access vehicles, and the capacity to build structures which duly appear in the game world of other players, who can leave social-media-style 'likes' to show their appreciation. But the pacing is far snippier and more refined than in the first game – the result, it feels, of taking on feedback and recalibrating the balance between cutscene and action. Quality-of-life improvements abound. It's difficult to shake the feeling that this is the game Kojima and his team intended to make the first time around.

The pacing is far snippier and more refined than in the first game.

But then, within a few hours, it seems as though it's all over. Mexico has been reconnected in record time, and, in a dramatic climax, we see Bridges sustain a loss from which he may never recover. What now? The answer arrives quickly: Australia.

The switch to a new continent means more than a change of terrain. Something fundamental shifts. The task of reconnecting settlements is the same, but the texture is clearly different, as you acquire increasingly efficient and varied types of weaponry. You soon leave behind foot-based missions and start to use upgradable vehicles. Then you begin to receive missions in which you're tasked not with delivering cargo but with clearing out enemy encampments. The realisation dawns: combat is far more central to Death Stranding 2's loops and rhythms than in its predecessor, where you were almost always outgunned and therefore encouraged to avoid conflict.

"The first game was like the Silk Road," Kojima explains. "It was about extending connections across a country, to allow useful supplies to travel. But the flipside is that negative things can travel more freely too: cockroaches, violence, drugs." Death Stranding 2, then, is intended to show the risks of interconnectivity. "It's represented by the prevalence of weapons. I'm trying to conjure the era of the East India Company, when resources could move freely around the world but, at the same time, this enabled these private companies to become more powerful than governments."

While it's still possible to use stealth, popping out of the tall grass to take down a dawdling security guard, for example, the game encourages a more direct approach. You may approach an enemy encampment from a rocky outcrop, set down your now-removable backpack, build a lookout tower that enables you to mark and track every foe, then use your sniper rifle to take out each one in series. It's all pleasingly taut and game-like and feels, in fact, like a concession to those players who bounced off Death Stranding's eccentricities as well as Kojima reconciling with his own past. Squint and you could be forgiven for thinking you were playing – whisper it – a contemporary update to Metal Gear Solid 5.

"I felt that myself when I played the game," Kojima admits when presented with the comparison. Drawbridge, the company you now work for, has the use of a futuristic airship, the DHV Magellan (named after Ferdinand Magellan, the 16th-century Portuguese explorer who became the first to circumnavigate the globe), which doubles as a movable base of operations, housing Bridges' living space. "When you return to your bed on the Magellan, it's the same feeling as returning to the plant in Metal Gear," Kojima says. Nods to and echoes of his former work abound. While staying in Bridges' accommodation in any of the bases – static or movable – you can spend some time playing a series of challenges in VR that are almost indistinguishable from Metal Gear's beloved VR missions. Even the sound effects are similar. There are traditional boss battles, too, complete with glowing weak spots.

Even so, the new focus on combat is surprising (even if the bullets you fire are described as tranquillisers rather than deadly projectiles). Death Stranding was clearly designed to upset the expectations of Kojima's audience; it was a game about striding out into the world to make connections, rather than sneaking around with a silenced SOCOM. Beneath the strangeness lay a radical design ethos. Death Stranding wasn't about winning, conquering or killing. It was about carrying, balancing, connecting. It introduced a system called the Strand mechanic: players could leave behind ladders, ropes and structures in their own games that would appear in others', anonymously aiding fellow travellers they would never meet. This asynchronous multiplayer design was an elegant metaphor for interdependence. In helping others, players helped themselves.

When James Cameron came to make the sequel, Aliens, he made a very smart decision to make the film not about horror, but about action.

"I have a 'stick and the rope' theory," Kojima tells us. "So many games are just about the stick. Even in games where you're connected with each other online, everyone's just battling with the stick." The rope, he says, is something used to wrap around things and bring them toward you. "In Death Stranding I wanted to make a game that was all about the rope. The sequel balances the stick and the rope."

To explain why he made this adjustment, Kojima settles into one of his favourite themes: comparisons to cinema. "When I first wrote the draft for Death Stranding 2," he says, "I referenced to my staff the first two Alien films. The first Ridley Scott film was so frightening. There were face-huggers, and monsters bursting from people's chests, and at first nobody knew what it was all about." But by the end of the film, he says, the audience had seen the alien, and understood the rules of the universe, so it was no longer frightening. "When James Cameron came to make the sequel, Aliens, he made a very smart decision to make the film not about horror, but about action. It gave the story a new dimension, which was unfamiliar. That is what I wanted to do with this sequel. Everyone understands Death Stranding's world, so now we've introduced battles to give it this new dimension."

The new focus on combat will appease those players put off by the first game's passive approach. But Kojima has not shied from difficult themes to go alongside the fighting. Grief is a central consideration of the game, a keen presence for Bridges, for whom the burden of loss is something he must carry physically.

One of Kojima's parents died when he was a teenager, so he is intimately familiar with loss. His father came home from work one day, fell down, unconscious, and started shaking. The family called an ambulance. Kojima travelled to the hospital with him. His father's eyes were open all the way, but he was unable to speak. Kojima felt his father wanted to tell him something. He never found out what. In this way, Kojima lost his innocence and, to a degree, his childhood. He spent his teenage years having to care for his family, making decisions for which he felt unprepared and ill-equipped. "The loss of my father was a major theme in the Metal Gear series," he tells us today. "Those games explore the theme of how you surpass your parents. Death Stranding looks in the other direction: you assume the parent's perspective, looking toward the child."

One of the game's central questions focuses on the story of Bridges' baby, Lou. Kojima has a son himself. "You think you know everything about your son, but there are some things that you don't," he says. "In the first Death Stranding, Sam travels together with Lou, but he doesn't interrogate who Lou is very much. In the sequel, that has changed. It's like how an adoptive parent might not know everything about their child. They might have questions. That's the emotion I wanted to elicit."

Narrative intrigue abounds, but so do more traditional game-like elements. This is a work stuffed with design ideas, with upgrade trees and satisfying incentives. Completing deliveries contributes toward a five-star rating for every facility and settlement in the game, and each time you achieve a new star rating you're rewarded with tools, weapons and upgrades. Facilities and structures that you or others build into the world can be upgraded using materials; with time, the idea is that the game will become crisscrossed with roads, ziplines and vehicle-charging stations. In this way, just about everything in the game can be turned into a mission, since everything is ripe for investment and nurture. Kojima's Rolodex of celebrity friends adds a less traditional incentive to explore and extend your reach, since many of the facilities are run by recognisable faces. As before, these cameos can be a little distracting, but at the very least they always leave an impression.

I've never wanted my team to grow larger than 150 people.

It's the astonishing degree of depth and variety elsewhere that makes the real impact, though. There are wildfires, natural disasters and all manner of inventive online features which, as in Hidetaka Miyazaki's work, allow players to collaborate in mystical, indirect ways. And while the fundamental tasks could be described as industrialised fetch quests, the cargo ranges from vinyl records to pyjamas and live animals, the ways in which they can be ferried expanding accordingly.

Kojima claims the game provides at least 70 hours' worth of adventure. The scale of the production – and the sheen with which everything is delivered – is particularly notable when you consider the comparatively small size of its development team. "I've never wanted my team to grow larger than 150 people working on one game project," Kojima says. His friend, Mad Max director George Miller, once told him that his instincts were correct, and that nomadic sheep-herding communities limit their flocks to 150 sheep, this number being the limit of what a human being can realistically track. "I talked to George last year and he congratulated me on keeping the team small," Kojima says. "I had to admit I went a little over 150, and we laughed about it."

It's easy to assume that Kojima Productions, with its extravagant HQ turning out such a lavishly produced sequel, is a blockbuster studio, but Kojima insists his work has an independent spirit. He sees himself as the head of a family, a role he has had to assume from childhood, and says he regards raising children and raising his young staff as the same. And while the director's handprints are as visible on Death Stranding 2 as the impressions the BTs make in the soil whenever they approach, it's clear that the game is the result of manifold creativity from a team that has been allowed to express itself in countless ways.

Always eager to reach for a second metaphor, Kojima also compares his staff to apprentices in a kitchen. Yes, he wants them to start by washing dishes, but only so that they can work their way up and one day be able to open restaurants of their own. He resists the idea of an assembly-line studio in which each developer handles only one task; instead, he wants creators who understand not just the "bun" but the whole "hamburger" – the lighting, the systems, the emotions. It's a vision of mentorship not as delegation, but as artistic awakening – and in Death Stranding 2 the results of this growth and development are clear. Yes, this is, as advertised, a Hideo Kojima game. But it's run through with an ethos that, in time, could outlive even the man himself.

Thinking of catching up on Kojima's past work before you set out on your delivery route? We've got the best Metal Gear games ranked to get you started. More from Edge? Vampire Survivors kicked off a game development gold rush, but has a legitimately new genre emerged between the cash-ins?

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.