From The Archives: Iain M Banks Reader Interview

In a tribute to the bestselling SF author, here's the feature from SFX issue 202 where Iain M Banks answered your questions!

In a tribute to the late bestselling SF author, here's the feature from SFX issue 202 where Iain M Banks answered your questions!

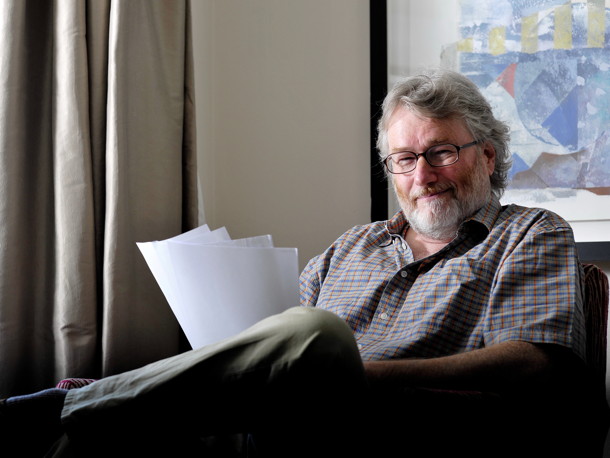

Back in 2010 ( issue 202 , to be precise), Iain M Banks agreed to take part in an SFX Fannish Inquisition. You know the format by now: readers get to ask the questions. We trapped Sun-Earther Iain El-Bonko Banks Of North Queensferry (as he once called himself according to the naming conventions of the Culture) in a London hotel room and he bravely answered as many as he could. Sadly, Banks passed away a few days ago from cancer; we are left with our fond memories of occasions like this and we thought we'd share this feature on the website this week.

With 1987’s Consider Phlebas , Iain M Banks introduced us to the Culture , a hedonistic but well-intentioned utopia of powerful AIs and space-faring posthumans. At the time of this get-together, Surface Detail was about to come out, in which the novelist ponders what afterlife a near-omnipotent society might create for itself. We met him in a swanky hotel on London’s Aldwych during a rare sortie from his Scottish hideaway, and threatened him with your questions. “Bring it on!” he laughs...

How long did it take in your writing career before you could officially state your profession as “full-time author”?

Joe, Birmingham

Even before it took off, actually! I went on this big hitchhiking tour in the 1970s, and although I’d never had a word published at that point I put “writer” on the passport form. You have a passport for ten years and I was 18 so I thought, “I’m not putting ‘student’ on this! In ten years time I’m bound to be an established author.” So I predated my writing career by several years when I first wrote it down on a travel document!

In your novels morality figures prominently. Did you find yourself so disgusted by what humanity is capable of that you had to invent the Culture and set off our darkness against their light? To what degree are you teaching us ethics through your writing?

Adam O’Toole, SFX.co.uk

I think every creator – artist, writer, blogger even – would like the world to think a bit more like them. Writers have a platform to mouth off from so certainly there’s an element of that. It’s hidden beneath all the bluster and action, but yes, the Culture has a very definite moral point of view. It’s very wishy-washy liberalism... except with hyper-weapons! A lot of the interesting stuff in my novels is where the Culture departs from the way it ought to behave. I’m kind of a purist about these things and I find myself being sceptical about compromises. I don’t accept that you ever have to do bad things to achieve good things – that often means the things you were trying to achieve weren’t worth doing in the first place. It’s such a slippery slope. A lot of people in charge of the gulags thought they were doing the right thing at first, because they were bringing on a better society. And if it meant a few people suffered then that was acceptable because they were working towards a communist utopia... I’d like for the Culture to better reflect the principle that you should not do these things ! But alas it does, because now and again Special Circumstances decides something needs to be done. So yes, [assumes comedy voice] it’s a moral discourse, that’s what it is, mate!

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

You’ve previously said the Culture represents your own personal idea of a secular heaven... so what prompted you to explore the idea of digital heavens and hells in books like Surface Detail ?

Sam Thompson, London

I think the formulation of an afterlife is part of the course of civilisation, something that inevitably happens in the sequence of a sophisticated society. I looked at the process of how a society would change over time; it would be remarkable if a society never thought about a concept of heaven. But as soon as you start visualising heaven you start thinking about hell. You might think, “Would they really want to build hell?” But some buggers might actually! So then you have the background for some serious moral conflict. That offers enormous possibilities in terms of writing fiction. [How does that fit alongside the concept you already introduced about people who “sublime”? – SFX ] It’s an add-on, it’s not the same thing. In Surface Detail I drop a subtle hint that I’ve finally decided what subliming actually is! I’ve been deliberately vague for many a year now, but I reckon it’s disappearing into the hidden dimensions, dimensions wrapped up inside superstrings. That’s where you go when you move on! This digital afterlife stuff, however, is still happening within the material galaxy that exists in our universe. When you’re inside the virtual reality of the new afterlife you’ve still got an off-switch, something could happen to make it all go away. Whereas if you sublime, there’s no switch-off, and you don’t have a link back to reality – people have chosen to vanish and not to link back.

Is there any chance you would tackle the early history of the Culture and how it came together?

Peter Kenny, Facebook

It has occurred to me. How far back, I’m not sure. Consider Phlebas is very early in the chronology and that’s still thousands of years after the Culture has coalesced! I hinted at something interesting when I wrote the line, “After the Culture’s formation, which was not without its vicissitudes...” I’d be surprised if (eventually) there wasn’t a novel set before Consider Phlebas . It might tax me to go too far back, though – I wouldn’t know what technology to leave out!

You’ve said your characters serve the plot, not the other way around. What’s the closest any character has come to gaining control and running off with the story?

mattc73, SFX.co.uk

Only Sharrow from Against A Dark Background . She’s meant to be in an auditorium and some heavies approach her to brow-beat her... and she turns on them! That wasn’t meant to happen. The way I plan novels, things are supposed to happen in a certain sequence. Characters are not supposed to start talking back! I’ve heard some authors write this way and I love the idea but it doesn’t work for me, I can’t leave things open. It’s a very minor bit, Sharrow turns and threatens the two guys, and it felt right and I wasn’t expecting it. She’s a very assertive person, she wasn’t taking shit from anyone! So it felt right for her to be – I hate this term – feisty in that scene. Sharrow’s yet another of my female central characters who I’ve fallen slightly in love with. It’s terribly selfish of me, an onanistic sort of thing. The characters are all a part of me, even the bad guys (maybe especially the bad guys!). I’m a heterosexual guy writing a female character, but I can’t help feeling, “Yup, this is what I’d be like if I was a lady!”

I had thought Look To Windward might be the last Culture novel. The suicide of the Mind felt like a very fitting and moving finale to me. Why return to the Culture?

Howell Jones, email

Look To Windward was never meant to be the final Culture novel. I did include the fact that the galaxy had done a complete revolution as well as some matters of historical interest. But this all just refers back to the idea that the Culture can’t be around forever. There’s an end state of civilisation, and that’s where it’s ultimately aiming towards. It might finally evaporate and disappear but it will have to leave, and leave behind other people like itself. That’ll be its final triumph, in a way, so that’s what that pointed towards. The Culture isn’t going to last forever... but that doesn’t matter. I’ll keep writing Culture novels as long as I have interesting things to write about – I adore writing books set there.

Since this interview there was one more Culture novel, The Hydrogen Sonata . Farewell Mr Banks, and thanks for all the stories; our thoughts are with your family and friends this week. There is an online guestbook for fans to sign at http://friends.banksophilia.com/guestbook/ and you can read two further SFX interviews online: Iain M Banks's Heroes and Inspirations and one about The Hydrogen Sonata .