6 questions we have after watching Black Mirror Season 5

We explore the intriguing unanswered Black Mirror season 5 questions raised by the three episodes

Black Mirror season 5 has arrived, bringing with it a small curated set of bleak vignettes of the ever-encroaching near future. This time around the stories are more grounded and believable than usual, often not relying on some far-flung future concept but more toying with the technology we have available to us right now and how that is harming our daily lives. Season 5 is more grounded and believable than usual but therefore ends up being more cutting, hitting with the same narrative gusto as some of the series original provocative efforts. Regardless, we’ve still been left reeling, our mind full of questions about the premises behind each episode, the loose ends and the teases towards the in-universe logic of Black Mirror. In this article, we’re going to run through a few of our most pressing questions from Black Mirror Season 5.

Striking Vipers

Is VR in Black Mirror all part of the same product line?

Yes, apparently so. The first time we see the node that Danny uses to hop into Striking Vipers X (in order to begin exploring his sexuality with old friend Karl) it reads ‘TCKR’ on the box, which is the company responsible for the reality-simulating San Junipero experience. Clearly, they’re into games as TCKR is short for Tuckersoft, the company who created the troublesome Bandersnatch game that tortured poor Stefan in the interactive special. TCKR has also been seen in Playtest on the cover of Edge Magazine with the subtitle ‘Turning nostalgia into a game.’ There’s also the fact that the node used in Striking Vipers is almost exactly the same as the one used in USS Callister by Daly and his crew - down to the lame, eyes glazed player experience. The theory then is that Tuckersoft eventually became or inspired TCKR, which was later co-opted and used as a medium by the developers in USS Callister to create the game in which Jesse Plemons played dictator. Who’s pulling the strings though, and where did the leap in technology come from? We just don’t know yet. Spooky.

What are the limits of Black Mirror’s vision of virtual reality?

In Striking Vipers the constructs of modern monogamy are deconstructed by Danny and Karl’s use of virtual reality to get busy. Most telling is how it resolved with a compromise - where Danny’s wife would let him use it as a means to battle his urges as long as she could spend a night with another man, in order to save the sanctity of their marriage - instead of accepting the virtual polyamory. It’s a fascinating solution, but it feels believable, and the only reason we haven’t seen something totally analogous in the real world is that the technology isn’t quite there. So what are the limits of Black Mirror’s vision of virtual reality?

Clearly, Danny and Karl are totally outside of their own bodies when they’re playing Striking Vipers X - their brains are doing all the talking, punching and boning. There is no head mounted display in sight, rather the TCKR system plugs into the brain and accepts input from there. Alas, as Danny’s post-VR erection proves (and Karl’s clear affinity for Danny over so-called ‘rubber dolls’ and polar bears in-game) this VR system has an effect on the player in the real world after all, even if they aren’t truly there.

Through some ‘extra content’ in a Tekken/Street Fighter fighting game they can form a genuine human connection between each other even if they aren’t physically there together - one that doesn’t transmit back to real life. Is the lust felt between just the avatars or the people behind them? Can they truly feel the physical sensations? The show suggests they can, as it appears to ruin sex with both Danny’s long-term partner and Karl’s one-night stands. It suggests that the VR in Black Mirror goes beyond games and is a more transhumanistic experience than something like Beat Saber.

We know that the escapism doesn’t stop there given that the USS Callister episode showed us a seemingly limitless toybox which Daly populated with his subjects - it suggests people can completely lose themselves to this kind of VR and create anything they want with strands of DNA. Players will no doubt wonder whether the real world is worth it over an uncompromising controllable hedonistic experience within a virtual space.

This is made even more interesting when you consider the technology behind it. In Black Museum its explained in a roundabout way by TCKR’s Sympathic Diagnoser, which allowed Dr Dawson to feel the pain of others (which turned him into a murderer) - clearly this tech is being used in a different way here to redistribute orgasm regardless of gender (we know this thanks to Karl’s distinction of it being more of an orchestra than a guitar solo.) So where does this technology end? Where are its edges - can people simply live within virtual reality in Black Mirror’s envisioned future and enjoy all of the most impossible to simulate pleasures of being human? It sounds silly but if it can simulate pain and pleasure - can people die within virtual reality? And what does that do to the body in real life? I guess we’ll learn more as virtual reality recurs in future Black Mirror episodes.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Smithereens

How far does Smithereen’s web of societal control stretch?

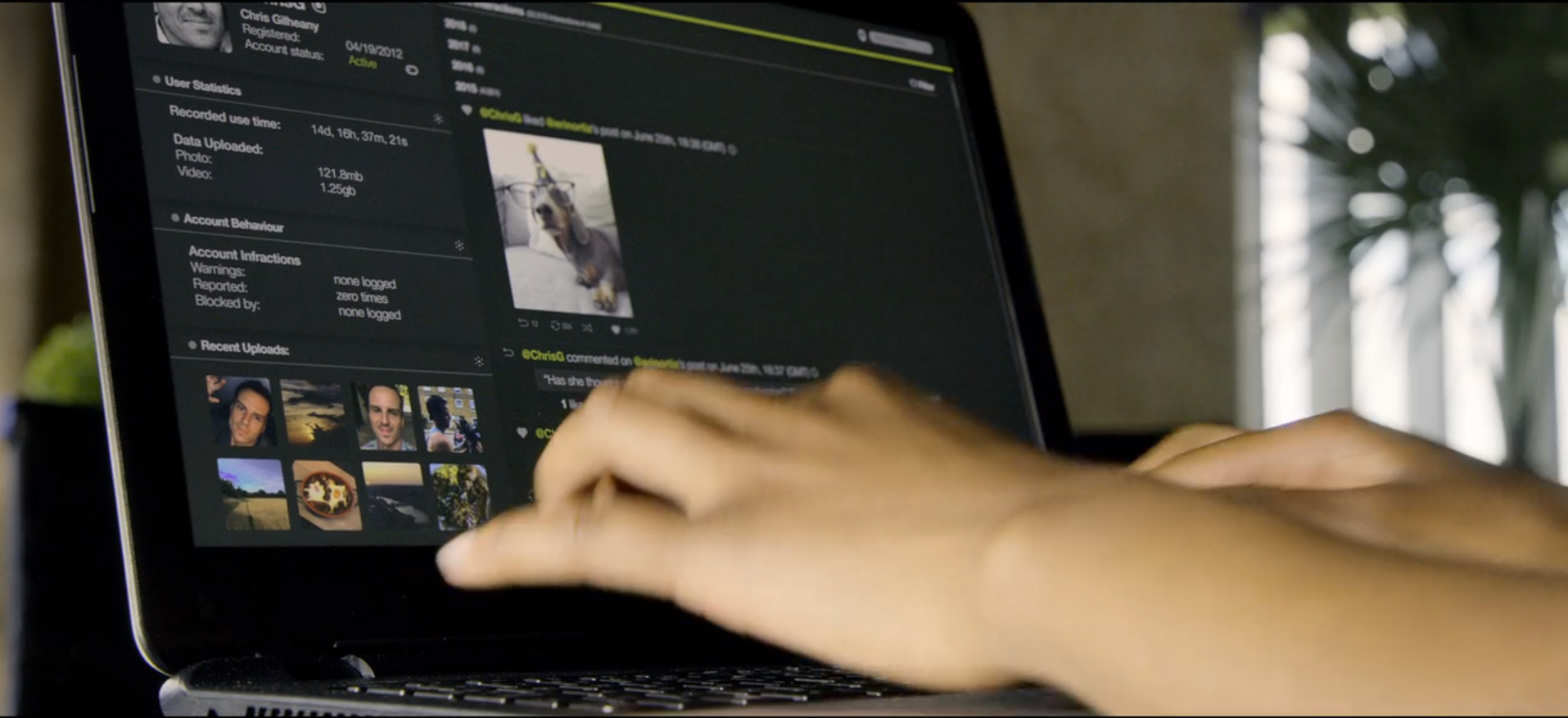

In Smithereens, we’re introduced to Christopher Gillhaney, a man suffering from extreme trauma after the unfortunate passing of his wife in a car crash. We learn that he is deeply upset with how globalised and digital the world has become, something he uses to his advantage when he kidnaps a Smithereen intern to hold him ransom in order to talk to its CEO, Billy Bauer. One of the more fascinating subplots of this episode is how much the social media app oversteps the British Police and the FBI during the course of the hostage situation. What appears to simply be Black Mirror’s version of Twitter quickly becomes something far more sinister.

The American subsect of Smithereen almost immediately pulls their case file on Gillhaney, giving them first access to his name and social cloud - they have a system to establish how much of a threat Gillhaney is given his posts on social media. Within this profile they start to understand everything about his life, deducing his trauma and motive from the absence of his social media posting after his wife has passed. In many cases, the app team are ahead of the police force on the investigation, albeit from another country, raising serious questions about the data storing techniques of real-world social media companies.

Eventually, they abuse their power to tap Chris’s phone, which gives them a direct listen line to his car, something Chris doesn’t anticipate (this inevitably leads to his death.) During this time the conversation is translated into text instantly, and his responses are fed to a social psychologist who later goes onto curate a line of messaging for negotiating and calming Chris down from his erratic position given the way he operates. Even more damning is when Bauer - the aforementioned Smithereen CEO - uses ‘God-Mode’ to take the reins off of Smithereen, giving him access to any connected device he wants, going against his employees’ warnings in order to talk to Chris directly.

It raises questions about how social media companies now have more of a data profile on us than even the police force do, to the point where in Black Mirror they’re constantly relying on them to unlock phones and understand criminals with their global data. It displays a huge power imbalance that big tech companies have over national governments - to the point where they can deeply influence elections and criminal investigations. If they can do this to Chris they can do it to everyone, seemingly without remorse and with a divine belief that they are the arbiters of fate, not the justice system.

Terrifying food for thought, made even worse by the revelation that there are many apps like Smithereen holding back data from their users - one early subplot is about a woman who wants to understand her daughters passing but can’t get into her locked social media account, with the big tech company unwilling to help on a person-to-person basis, but happy to interfere when events start to affect their public-facing image.

What point was Chris Gillhaney trying to make?

One thing that isn’t explained in great detail is the reason behind Chris’s particular actions in the episode. His clinical tactic of kidnapping a Smithereen employee backfires in multiple ways, but he still eventually negotiates his demand for a phone call with CEO Billy Bauer - yet this only happens after his team warn the meditating creator away from it - a spot of reverse psychology appears to excite him.

Chris appears to want to atone for something when he reveals that it was his fault for his wife’s passing due to the fact he was checking his Smithereen feed whilst driving - not because the other driver was drunk. Perhaps Gillhaney wanted to impart some guilt on the creator, who appears to be shirking responsibility for his creation, his original vision now curated by the committee as he wanders off to silent retreats. You wonder whether Chris actually got what he wanted - Bauer’s explanation of the “tweaked endorphin targets” were rooms full of employees working on making the app as addictive as possible. This confirms Gillhaney’s suspicions that Smithereen is only interested in building a profile and controlling users more than it ever was about communicating and making people closer.

The overarching point is that whilst it may have been created with good intentions, Bauer’s backseat CEO status whilst the cogs tick and his employee’s focus on data-reaping and money-making have caused far more harm than good. Perhaps Gillhaney wanted to actually point this out to Bauer outside of his inner circle, his echo chamber as the travelling CEO doesn’t seem to want to be responsible for his creations. Alas, this doesn’t seem to phase him too much as he returns to meditation.

Outside of attempting to affect the CEO in a way not normally possible (no random user can simply schedule a meeting with Jack Dorsey or Mark Zuckerberg, to use a real-world example!) Gillhaney makes his point in what he leaves behind.

When he’s shot by a police sniper as Jaden attempts to stop Chris from using his gun on himself, the news disseminates around the world via hashtags, leading to a moment notification that arrives on the phones of people in all different parts of the world leading their own lives. Some may have been familiar with Chris and the ongoing situation, others maybe not, but the point is that all of them were privy to his downfall, able to watch it develop in realtime and resolve in an instant without any skin in the game, transmitted to every Smithereen user regardless of whether they’re interested in it or not - it’s just newsworthy, and that’s the point. The final damning scene is when a handful of users around the world glance at their phone quickly before switching it off and getting on with their day. Gillhaney (and Charlie Brooker via the script) clearly wants us to see from an outside perspective how strange it is that we open ourselves up to tragedy on a near-daily basis only to register that information and carry on with our day. A life reduced to a notification. In that sense, Chris made his point very clear, in the most ‘Black Mirror’ way possible.

Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too

How do Ashley Too and Ashley Eternal function?

Easily the most technologically intriguing episode of the bunch, Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too deals with the effect of pop stardom on young children, and how engagement and fandom can be monetized. This episode is full of scary, ambiguous technology - and despite being only a few years into the future, it’s still hard to explain how it all actually works. Though, we can deduce some aspects of it via hints throughout the episode.

Ashley Too is the Amazon Alexa/Google Home inspired smart device with an even more sinister aspect to it - it’s modelled around the personality of a pop star (played by Miley Cyrus) who is there in robot form to befriend lonely young girls and slowly turn them into copies of said medicated popstar, teaching them dance moves and inspiring them to be themselves with faux-happy motivational quotes. Of course, this is something Rachel is the perfect customer for, given her lack of friends and obsession with Ashley O. This Black Mirror vision of a smart device is far more advanced than the rudimentary options available to us in the real world - it appears to simulate actual human conversation, and respond in turn to emotions and questioning, albeit within the realm of Ashley’s code-limited psyche.

Also, it’s always listening so it’s hard not to question whether the point of the device is to reap data from users (perhaps to sell?) as it immediately starts to ask Rachel worrying questions that could be answers to passwords like family details and former moments of grief. When Rachel uses a Snapchat filter we see her face being scanned by the app. Also, Ashley Too appears to be able to learn and adapt to the user acutely - evidenced by the scenes where the robot starts to taunt Rachel’s punk sister Jack and is woken up during a news broadcast about the real Ashley O and starts to malfunction.

We see later on that Ashley Too is a genuine simulation of the real person - not just an A.I. developed to be like her. It uses the systems behind her actual brain within the hardware and can be untethered to exist as a robotic mini-version of Ashley which shows that transhumanism is a theme this season and something that totally exists within the realm of Black Mirror - robots with their own full autonomy.

Ashley Eternal (the Hatsune Miku ripoff that her manager wants to monetize whilst the real star is in a coma) exists in a similar manner - by 3D scanning Ashley’s body and using her coma dreams they can continue with an amalgam of pitch-shifted voice clips to create songs. In a world of neural networks and uncanny valley deepfakes that can transpose faces onto and string together voice clips to impersonate public figures, this technology isn’t too far off - virtual pop stars already exist through vocoders and hologram technology - how would we notice something was off?

What’s up with Rachel’s father and his MAUZR prototype?

One subplot in this episode that got barely enough screen time but ended up being very important was Rachel’s dad and his entrepreunerial extermination business. As well as embarrassing his daughters with his Dumb & Dumber dog car - he was working on a prototype rodent-killer robot that appears to adopt or learn from the brain functions of rodents themselves, creating an autonomous animalistic killing machine. Does that sound familiar? It sounds like the kind of technology that could lead to murderous machines akin to the fiends seen in the black and white episode Metalhead - a dystopia where society is overrun with quadrupedal autonomous robot killers.

MAUZR is perhaps some kind of taser-first precursor to this - though it seems strange that some dad in the middle of nowhere could uncover and develop this technology in his basement. Jack later uses it in the episode to knock out one of Ashley’s manager’s goons after its overpowered capabilities are shown when the dad tests it on a real rodent, which the MAUZR hunts and kills with efficiency.

Even more interesting is that later the technology is used to unhook the limiter on Ashley Too’s artificial intelligence, giving her freedom to cuss and be herself around the protagonists, kicking off the episode’s climax. What’s scary is how quickly this is glazed over - Rachel’s dad has somehow managed to develop software that maps and can alter the brains of humans and animals in his basement... absolutely terrifying, world-altering technology that is apparently fairly easy to use. This opens up another transhumanistic vein where if they can put a snapshot of Ashley O’s entire mind into a robot, it could be transferred to another human or an animal, or vice versa. Hopefully, someone will dig deeper into the origins of MAUZR and the technology behind this scene, as it’s perhaps the most harrowing aspect of this non-chipper episode.

If the latest episodes of Black Mirror don't float your boat, why don't you check out whether you agree with our ranking of the best Black Mirror episodes of all time?

Jordan Oloman has hundreds of bylines across outlets like GamesRadar+, PC Gamer, USA Today, The Guardian, The Verge, The Washington Post, and more. Jordan is an experienced freelance writer who can not only dive deep into the biggest video games out there but explore the way they intersect with culture too. Jordan can also be found working behind-the-scenes here at Future Plc, contributing to the organization and execution of the Future Games Show.