11 reasons David Bowie is a sci-fi icon

Remembering David Bowie...

David Bowie was more than just a musical revolutionary. One of the truly crucial artists of our time, his influence reached into every part of culture and entertainment - including the worlds of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. A year on from his death we pay tribute to the late Starman by spotlighting 11 reasons why he was (and will always be) an icon of the fantastic, the cosmic, and the otherworldly.

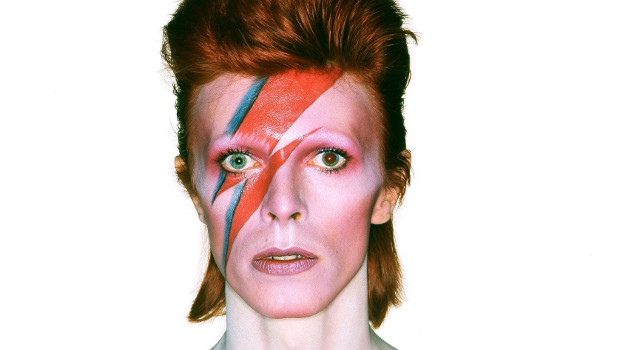

There's a starman, waiting in the sky...

David Bowie was the lightning-faced heir to H.G. Wells, Arthur C. Clarke, and J.G. Ballard, writing an anthology's worth of science-fiction stories in song form. 1969's breakthrough hit Space Oddity was a Kubrick-indebted fable for the Apollo age, charting the melancholy orbit of abandoned space pioneer Major Tom. Oh! You Pretty Things told of the inescapable rise of Homo Superior, a mutant strain of young dudes poised to claim the world. Bowie discussed the song with TV producer Roger Price, who repurposed the term Homo Superior for cult 70's show The Tomorrow People (though Bowie, a Marvel fan, doubtlessly cadged it from Lee and Kirby's The Uncanny X-Men).

Drive-In Saturday, meanwhile, was a portrait of a post-apocalyptic civilisation who turn to antique films to rekindle their sex lives ("it's hard enough to keep formation/amid this fall-out saturation"). 1972's Starman was the key text, though. The tale of an alien messiah making contact with mankind over night-crackling radio waves, it found Bowie descending on the nation's living rooms like some dad-baiting glam rock mothership. His immortal Top of The Pops performance presented a pan-sexual stick-insect in a comic book jumpsuit, a cadaverous Pied Piper for every disenfranchised dreamhead marooned in the charcoal cul-de-sacs of British suburbia.

Riding currents of hazy cosmic jive, he was a genuine shudder of the uncanny among the slap-daubed, lycra-bursting brickies who routinely stomped around the Top of the Pops studio. The rise and fall of Ziggy Stardust had begun.

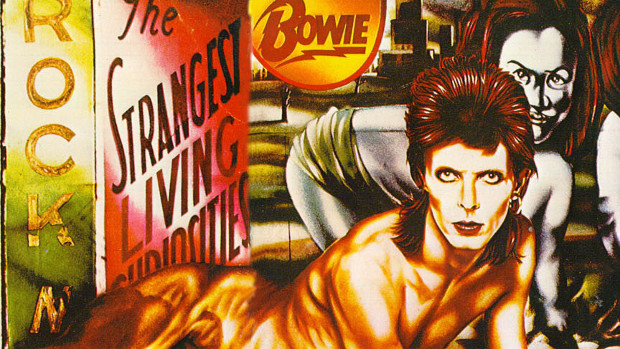

"Any day now... the year of the diamond dogs!

Bowie wanted to stage a musical version of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, fusing rock, roll, and totalitarian rule. Orwell's estate baulked, but explicit echoes of this doomed project remained on classic 1974 album Diamond Dogs, not least in such song titles as Big Brother and 1984.

Elsewhere Bowie fashioned a feral, post-apocalyptic Earth of his own design. A Clockwork Orange-inspired dystopia rich in ruined carnival detail, where "red mutant eyes" flash their menacing gaze at the lethal streets of "Hunger City" and "ten thousand peoploids split into small tribes/coveting the highest of the sterile skyscrapers". Oh, and there were "fleas the size of rats" and "rats the size of cats", just for good measure. The scariest future in rock.

They're stuck! Ill never get them off!

Bowie dreamed of bringing Robert Heinlein's Stranger In A Strange Land to the screen but ended up in The Man Who Fell To Earth, Nic Roeg's enigmatic adaptation of a comparably-themed novel by Walter Tevis. He's immaculately cast as Thomas Jerome Newton, an exiled, cat-eyed extra-terrestrial from a dying world, come to Earth in search of water and ultimately corroded by alcohol and information overload. The enduring image of Newton hooked on a relentless drip-feed of televisions absolutely foreshadows our own media-drenched age (just imagine the scale of his Twitter addiction).

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Bowie's glacial, insectile charisma was a perfect fit for this most alienated of aliens and he clung to the character during his cocaine-numbed LA lost years, placing images of Newton on the covers of Low and Station To Station. And, fair enough, it was officially the greatest haircut he ever had. Bowie recently revisited the character in his musical Lazarus.

What a fantastic death abyss!

It's 1995, and Bowie's in retreat from the stadium-conquering populism of his peroxide-powered 80's. In jealous debt to the uncompromising weirdness of fellow icon Scott Walker, the album 1.Outside aims to reposition the fallen Mr Showbiz as an edgy cult artist, on the margins of the mainstream (the clue's in the album title). It was a dark, demanding concept piece, following near-future gumshoe Nathan Adler as he investigates a slaughterous new craze sweeping the art world.

Subtitled The Ritual Art-Murder of Baby Grace Blue: A non-linear Gothic Drama Hyper-Cycle, it was an uneasy collision between the tech-noir of Blade Runner and the grisly viscera of Se7en, and came with a deeply inscrutable text story written by Bowie himself. Part of a trilogy that never was, it's an album that leaks pre-millennial dread like blood from the wounded corpse of one of its ritual murder victims. And still the crowd cried for China Girl at the concerts.

It's the freakiest show

What other rock star can lay claim to christening two cult TV shows? Named for the greatest song Bowie ever wrote (that's a fact), Life On Mars followed the saga of time-lost copper Sam Tyler, forcibly relocated to the Brut-splashed fog of the 70s. Sequel show Ashes To Ashes took its title from Bowie's 1980 number one (and riffed on the imperishable visual of Bowie as a post-apocalyptic Pierrot in that song's video).

The final episode of Ashes found plain clothes Anti-Christ Jim Keats phoning a superior named Dave an ad lib on the part of actor Danny Mays that suggested a rather more chilling connection between David Bowie and the shows retro-styled afterlife.

Sarah, beware

For a generation of hormonally-fizzing young girls, 1986's Labyrinth was an unforgettable introduction to David Bowie. He may have been rocking a frightful wig but this codpieced, crystal ball-twirling Goblin King was a potently alluring figure. A gateway freak, a first glimpse of the darker, lustier world waiting beyond those boy band posters on the bedroom wall.

"I thought, what the hell, I've done Laughing Gnome," said Bowie of his turn in this Muppetational collaboration between the empires of Jim Henson and George Lucas. "Might as well go all the way. I never thought in twenty years I'd come back to working with gnomes".

I can stare for a thousand years

The midnight movie of choice for ageing goths everywhere, 1983's The Hunger was a Tony Scott-helmed slab of style-mag horror, loosely adapting Whitley Streiber's novel. Scott cast Bowie as an immortal cellist, the centuries-defying consort of a vampiric Catherine Deneuve. He won the most memorable scene in the film, ageing to death in a doctor's waiting room.

Bowie possibly rued entering the horror genre: "I must say, there's nothing that looks like it on the market," he said at the time. "But I'm a bit worried that it's just perversely bloody at some points".

I found something and then there they were!

Bowie delivered a cherishably baffling cameo in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, David Lynch's equally unfathomable big screen take on his own cult murder mystery show. He played FBI agent Phillip Jeffries, a reality-bothering Fed who steps out of an elevator two years after vanishing from existence. A seemingly spectral figure, invisible to the naked eye but detectable on CCTV, Jeffries imparts some impenetrable but ominous warnings then promptly disappears again (possibly to spend a decade working on a new album in secret).

"My character is an intensely over-travelled upholder of the law," said Bowie, who confessed to stealing the belt that Jeffries wore. "He has seen too much and has little ability to do much about it". Not dissimilar to the perspective of a rock god, really.

"Morning star, you're beautiful

The man who fell to Earth was a fallen angel too. Just take a look at Lucifer Morningstar in Sandman. The former lord of Hell is modelled directly on David Bowie, at writer Neil Gaiman's insistence.

"Neil was adamant that the Devil was David Bowie," revealed artist Kelley Jones in Joseph McCabe's book Hanging Out With The Dream King. "He just said, he is. You must draw David Bowie. Find David Bowie, or I'll send you David Bowie. Because if it isn't David Bowie, you're going to have to redo it until it is David Bowie. So I said, okay, it's David Bowie..."

The Fringe connection

We were later introduced to Thomas Jerome Newton, resurrected leader of the shapeshifters. Fitting, given Bowie's relentlessly chameleonic career. Oh, and the episode Five-Twenty-Ten showed us a copy of The Man Who Sold The World belonging to Walter, possibly the only man alive to have done more drugs than David Bowie in the 1970s.

"Freak out in the moon age daydream"

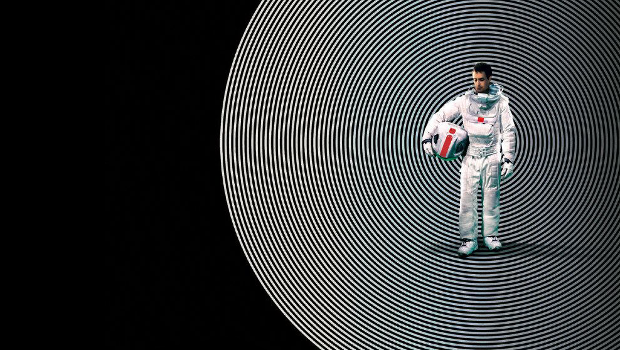

David Bowie's most lasting contribution to geekdom may just be his son, Duncan. Inspiration for Kooks, the single sweetest song in the Bowie canon, director Duncan Jones brought rare heart and intelligence to cinematic science-fiction. Moving from the faithfully old school trappings of Moon to the reality-tangling action beats of Source Code, and onwards to the epic fantasy of Warcraft and the noir near-future thrills of Mute. By his own admission, he was marinaded in fantasy from an early age, lapping up 2000 AD alongside his dad's choice in literary greats.

"If I like science fiction, it's his fault to an extent," Jones told French music magazine Les Inrocks. "He read me stories just like you give sweets to a child. If I didn't like them, we changed to another book and it always finished up with Philip K Dick, George Orwell or John Wyndham". Bowie Senior also encouraged his son's interest in filmmaking, staging Super 8 epics with Smurfs and Star Wars action figures on the kitchen table while the world believed he was lost in a hedonistic blur with Iggy Pop. Seems the creative exchange was mutual: Where Are We Now wasn't just the title of Bowie's media-melting comeback single in 2013; those are also the first words we see on screen in Moon.

Nick Setchfield is the Editor-at-Large for SFX Magazine, writing features, reviews, interviews, and more for the monthly issues. However, he is also a freelance journalist and author with Titan Books. His original novels are called The War in the Dark, and The Spider Dance. He's also written a book on James Bond called Mission Statements.