The reason why boss battles will never die

The golden dragon is to blame. Prior to the creation of Dnd, coded in the mid-’70s for the University Of Illinois’ pioneering PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations) system, it is generally agreed there was no such thing as the videogame boss. Developers certainly had little need for threshold guardians: games of the time were typically point-chasing affairs, shooting games, or recreations of sports such as table tennis and racing. Few were adventures and fewer still were designed to be conclusively overcome.

But Gary Whisenhunt and Ray Wood were making a complex-for-the-time RPG based on Dungeons & Dragons, and they decided there would have to be a way to finish their quest. The Orb was the solution: an ultimate treasure. After claiming it, players would retire to the Elysian Fields and even be enshrined on the title screen, at least in some versions. But to make this intangible bauble worthy of such esteem, and of the hard road before it, the Orb needed a suitable guardian – something impressive. Something to demonstrate your mastery over. And what better to guard a precious fantasy object than a dragon? The etymology of ‘bosses’ in games is more confusing – 1981’s Galaga was among the first to use it – but that fearsome serpent embodied the concept.

In the decades since, the boss has become one of videogames’ most enduring elements, performing many different roles. It is variously crucible, reward, teaching aid, story vehicle and final exam. Some common aspects of these encounters – the flashing weak points, the heavily telegraphed tells – have persisted right through gaming’s adolescence, surviving from the 2D arcade shooter to find new homes in the 3D worlds of today. Bosses’ ubiquity is puzzling, though, since as a whole they are notoriously uneven in quality. They can be the zenith of a game, or its nadir. So why, in this era of multimillion-dollar development and exhaustive playtesting, do so many still get them wrong? And how do you design a good boss fight?

There is no easy answer. With innumerable different shades of boss, much depends on the design goals a fight is supposed to achieve, but even an encounter that meets its brief may not be considered a good one by a game’s audience. There are, however, principles – guidelines that have emerged from decades of iteration and experimentation. And like so much else in gaming, the arcade would have a profound and lasting effect on the bosses of today.

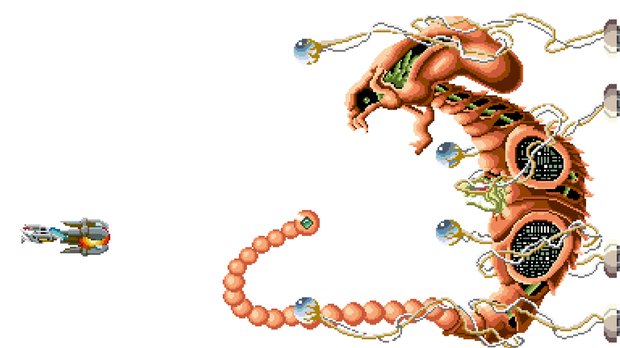

These enemies were initially about spectacle, made to stick in the mind and bring in the coins. The almost-screen-width mothership of 1980’s Phoenix – one of the earliest arcade boss fights on record – was barely more difficult than the levels themselves, but it offered a visual break from normal enemies. With limited system memory, this was the boss more as bonus than punishment, a chance for players to test their mettle against something more impressive than wave after wave of identical drones. Phoenix would also firmly establish the scale of a boss fight, with screen-filling enemies able to draw the eye across a packed arcade. But offering a Goliath to the player’s David had fringe benefits: there’s a psychological significance to being made to feel small and overcoming a larger enemy, although it is poorly understood to this day. Nonetheless, scrolling shooters would take this type of boss to ever-greater extremes.

An arms race began on the crowded arcade showfloor. Developers realised that bosses were a significant part of their games’ appeal, so they made them more elaborate. This birthed bosses memorable not only for their looks, but also their challenge, including R-Type’s Bydos. And with the high score table to climb, beating a difficult boss could earn you serious bragging rights. Cynics might argue that greater challenge also helped keep playtimes short and pushed players to spend more on credits, but Harry Kreuger, lead coder on Housemarque’s most recent love letter to the side-scrolling shooter, Resogun, refutes that.

“I don’t agree with the notion that arcade bosses were ever designed only to take players’ money,” he says. “I believe that to be a massive disservice to the games of that era and the brilliant design choices many of them made. That being said, of course the designers needed to ensure that play sessions wouldn’t last too long, but the experience crafted within those constraints still needed to be engaging, fun and rewarding, bosses included. So despite their coin-operated nature – or perhaps because of it – the good arcade games of that era ended up defining the dynamics of skill-based games to a huge extent. Those same design principles still apply universally to all skill-based games, regardless of whether they’re coin-operated or not.”

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Still, whether it was premeditated or not, the escalation continued. But not every game could rely on the screen-filling excess of scrolling shooters, and AI at the time wasn’t advanced enough to challenge a skilled human player in a fair fight. As such, fighting games soon resorted to imbalance or even outright trickery to make up the shortfall. Street Fighter II’s M Bison was one such cheat, capable of chewing through credits as fast as any Sinistar. Bison’s moveset was unlike any other in the roster, boasting more invincible frames, no-charge Psycho Crushers and Scissor Kicks, and massive damage output. In an era without YouTube, he was a fine way to dig coins from the pockets of gamers desperate to see, say, Dhalsim’s ending. Were he and his spiritual successors unfair opponents? Certainly, but with good reason.

“Fighting games are magical, and there are few genres with more meaningful, nuanced player options,” says Seth Killian, ex-lead designer at Sony Santa Monica and namesake of Street Fighter IV’s infuriating final adversary. “But fighting games are primarily built as a test of your decision-making and execution against another human. When you subtract the other human from that equation, they tend to fall apart. Building a genuinely challenging AI would be a major accomplishment in computer science, so instead designers usually just cheat. If you don’t, you’re signing up for a lot more work and the boss will probably still be too easy. So if you’re a designer tasked with creating a final legendary opponent and your choices are between weird and easy or stupid-hard, it’s easy to see why so many fighting games choose the dark side.”

The King Of Fighters series took that to extremes, its bosses frequently equipped with no-recovery special moves, infinite super meters, and the ability to react to player inputs instantly, effectively making them mind readers. But this is far from an SNK-exclusive problem.

The alternative, for fighting games at least, is to return to bosses as rewards, offering an oversized monster that provides a break from the normal gameplay, and using attacks that aren’t designed to be recycled in multiplayer matches. Marvel Vs Capcom’s bosses are an enduring example: Apocalypse, Abyss and Galactus all engulf the screen during different stages of the fight, offering attacks that can’t be blocked or interrupted in the same way as any other character, but compensating with hitboxes to match their stature. Skilled players have responded with their own combo videos, pushing the boundaries into hundreds of hits.

Boss-as-refresher suits the arcade modes of fighting games, since the real longevity and tests of skill come from other humans. Radically changing pace with a boss fight can ruin other genres, however. Deus Ex: Human Revolution is a story-driven action-RPG that’s built upon options. If you want it to be, it can become a nuanced stealth game with the option to do no harm (well, for most of its runtime). But that core game – before the Director’s Cut, at least – was compromised by its arena fights against superpowered opponents, which feel horribly incongruous. At best they’re out of character and at worst they throw up a blockade for otherwise-valid playstyles.

Uncharted 2 made almost the same mistake, with a final boss that feels at odds with the rest of the game. “The problem arises when you learn a set of good, interesting mechanics over the course of a game,” Killian says. “Your skills improve as you play, and maybe you even master those mechanics. Then you get to the boss, the final challenge, and for the sake of being ‘big,’ the designers abandon all those mechanics they’ve spent hours teaching you, and instead ask you to play what’s essentially some totally different kind of minigame. The boss may be huge, the music may be epic, but once you set aside the spectacle, the gameplay is often mini.”

A boss shouldn’t cheat the player by breaking established rules, in other words. That doesn’t mean it can’t add to what’s come before, or subvert the norm, but it shouldn’t ignore the fundamentals the designer has taught you up to the battle. “I really liked the way Dishonored handled its final encounter,” says Alistair Hope, creative lead on Alien: Isolation. “It chose to maintain the primacy of player choice over everything else, right to the end. The player was left to deal with the obstacle with the tools at hand and the skills they’d learnt over the course of the game. It really reinforces the belief that the player’s understanding of the world and choices of action mean something.” Dishonored’s solution is an elegant one to a relatively new problem: the sheer amount of tools, tactics and options games now provide.

Bosses can, in fact, be a powerful way to teach game mechanics. Dark Souls’ first boss battle is renowned for its difficultly, falling so early in the game that you are thoroughly under-equipped to beat him. For all but the most skilled, the only viable option is to escape. The lesson is clear enough: FromSoftware is not afraid to pitch you foes above your ability, and running away is perfectly reasonable when it does. Your rematch with the Asylum Demon, however, comes just 15 minutes later, and puts players in the ideal position for a falling strike, hugely reducing the monster’s health with a technique that can be used from any elevated position in the game. The rest of the fight against this mace-wielding titan teaches the primacy of evasion and blocking, of learning attack patterns and looking for openings – a valuable primer for the 40-plus hours to come.

Saurian Dash, author of Bayonetta: The Official Guide, agrees a tough-but-fair boss is an ideal way to grow your abilities. “I feel boss battles are like lessons, like obstacle courses,” he says. “When you master different aspects of the system, you improve at them and play the rest of the game better. If the system is deep enough, there shouldn’t really be an upper limit to what you can do; that’s what makes games like Devil May Cry 3 and Bayonetta so amazing. I can spend a week on one boss battle.”

But these bosses only work when a game has systems to teach. God Of War’s bosses are renowned for their titanic size and spectacle, but Dash finds them hollow. “There are so many games that are sort of like an interactive movie. Other games you need to really dig deep to find these little treasures in the system. You find a new trick in the system, and then you realise that you can do something else, and it goes on and on and on. [With God Of War], it’s horrible to say, it doesn’t sound nice, but I don’t get those breadcrumbs, and I don’t find those interesting things down the line. It’s like, ‘What you see here, this is the game, and there’s nothing beyond this’. That’s no problem, but I can’t make the system my own. I can’t push against the boundaries. It’s like the bar of expectation is lower. The best games, for me, are the ones where the bar is set extremely high and I’m like, ‘Why didn’t I see this before?’“

This, of course, can be a distinction lost on players unwilling to invest the time needed to appreciate a game’s intricacies and master its systems. “In Bayonetta, the transition from Very Hard difficulty to Non-Stop Climax is that you really have to crowd control,” Dash explains. “You really have to know the enemy attack signposts, know when to parry... People complain that you fight Jeanne three times, but each time she has a different move set, so you’re fighting three different bosses. It’s the same in Devil May Cry: the Cerberus fight actually works better in Dante Must Die mode, because the faster timing is more natural. In Metal Gear Rising, once you realise how the Blade Mode cancel works, it changes the game.”

Dash’s YouTube playthroughs are dazzling displays of this skill, but so far beyond the reach of most players as to be almost superhuman. Building for masters will inspire a level of devotion in a subset of the market, but can vastly reduce your accessibility. Batman: Arkham Origins’ Deathstroke fight is a case in point. It’s a battle of counters based on responding to aggressive volleys of attacks and then hitting back. Once you’ve got the hang of the mechanics, it’s beautifully designed – every attack illustrates Deathstroke’s character, and every single one can be countered. Until then, it feels frustrating and arbitrary. It comes early in the game and assumes a degree of understanding of Batman’s combo and counter systems. Gauged by the Twitter and forum backlash, that meant it was too much of a stretch for the audience.

“I’m very proud of the Deathstroke boss fight,” says Michael McIntyre, games director at WB Games Montreal. “I know that the reaction has been polarised on this particular fight and I think that’s fair. In hindsight, I think there are some things we could have done to help players prepare for it, but I wouldn’t change the heart of it. It was important to us that Deathstroke should feel like a complex and dangerous opponent. Our goal was to make Deathstroke look cool and test the player in a way that made them a little better at countering in combat, which is one of the core skills in the game. I think the first sign we achieved what we wanted was when we saw players lamenting that they only get to fight him once.”

The fight wasn’t so much the issue as the timing, and challenge and pacing are tough balances to achieve in the modern landscape. Unlike their ’80s counterparts, the budgets involved in triple-A development mean that few developers have the luxury of simply telling the player to toughen up. Games often have to sell millions of units to break even, so they have to appeal and not frustrate. One way or another, everyone expects to see the final cutscene. And yet making things too easy robs a boss fight of real achievement. That’s not to say every game has to mollycoddle players, though.

“Ideally, you want to dance on a thin line where the player feels seriously outclassed, but they don’t feel hopeless or really angry because of deaths they can’t understand or avoid,” Killian says. “There are some great examples in Dark Souls. [FromSoftware] use a lot of standard boss tropes like ‘brutal attack followed by briefly vulnerable period’, but the variety of attacks, ranges, their special effects, and the way the bosses move really help to set them apart. When you add that to the player’s own rich movement and defence options, you usually have the feeling like, ‘I could have pulled that one out! If only I had rolled!’ If the designer can keep the player feeling like there’s something clever they could have done to win, even if the odds are stacked against them, that’s the best-case scenario.”

The modern boss has to be many things to many players: challenging for experts, achievable for newcomers, a lesson, a reward and a way to define the game itself, especially when the game is built around its bosses, as in Shadow Of The Colossus. The Wonderful 101 highlights the problem with hidden depths perfectly. “What I found with Wonderful 101 is that it’s absolutely packed with stuff, but it tells you none of it,” Dash says. “There’s a visual language to the game, and once you get that – once your mind is open to the possibilities in the game – you see opportunities everywhere. What you have to do as a game designer is ask yourself, ‘Is my target audience going to persevere and have the mindset to look for these things?’ Because people will come across a problem with the game and stop there and go, ‘This feels broken’. I think a lot more needs to be done to open these things up for people.”

What developers often forget is that the ramp up for a major boss battle starts long before the player enters the arena. Time invested in building their skill in the early stages of a game will allow for better and more elaborate bosses in the later sections, where interest might otherwise wane. Pitch it right and the boss becomes both a means and an end: a way to teach and to reward.

“Bosses are intended to challenge the player,” says Kreuger. “The thing is that it’s not really possible to maintain the intimidation factor and impact of a boss encounter if it’s a total pushover, so making them too easy robs them of their purpose. There’s a great emphasis on ‘rewarding’ the player for their efforts, but I think the primary source of reward should be defeating the boss itself.”

Read more from Edge here. Or take advantage of our subscription offers for print and digital editions.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.