How a haircut changed the path of DmC: Devil May Cry

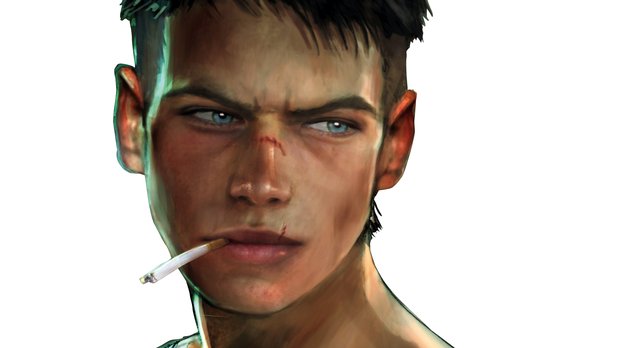

Rarely can there ever have been such a great fuss over a hairdo. It all began in late 2010 at the Tokyo Game Show, where Capcom unveiled DmC: Devil May Cry with a short trailer showing off the new-look Dante. Younger, grumpier and a good deal darker on top, this angsty smoker was nothing like the cocksure, silver-bobbed protagonist fans knew. The reaction was far from pleasant. Ninja Theory creative chief Tameem Antoniades puts it bluntly: “The vitriol was immediate, aggressive and relentless for the next two years. Without a second of gameplay being shown, it had been written off as a disaster in the making.” Looking back at forum threads from the time, you can see his point. “Kill it with fire.” “Is Dante emo and gay now?” “Ninja Theory is on crack.”

You’d forgive a studio for responding to a reaction like that by caving and trying again. At Ninja Theory’s Cambridge offices, however, visual art director Alessandro Taini was totally unperturbed. “As an artist, you’re a little a bit selfish,” he tells us. “You think about what you like. We were happy with the results, and so was the client. If I like something, and I don’t hear any complaints from the people paying my wages, then I’m OK.”

Despite the furore online, the client was indeed happy: Ninja Theory was doing exactly what Capcom had asked of it. At the time, the publisher believed western developers were the key to global success and was working with overseas studios on both new and existing IP. Keiji Inafune’s team was making a Dead Rising sequel with Blue Castle Games, a partnership so successful that Capcom would later buy the Canadian studio, rebadging it as Capcom Vancouver. Swedish studio Grin rebooted Bionic Commando, while Airtight Games in the US was making Dark Void. Results were mixed, of course – Dark Void tanked, Grin closed down, and Inafune left under a cloud to set up on his own – but at the time Capcom believed it was on the right path. Most of Capcom, anyway.

“There was some resistance internally, particularly from the original DMC team,” says Hideaki Itsuno, the director of DMCs 2, 3 and 4, who oversaw development of DmC from Japan. “But Capcom as a whole was in the mindset that we needed to collaborate with western studios. We could tell from titles such as Heavenly Sword and Enslaved: Odyssey to the West [which was still in development during DmC’s inception] that Ninja Theory were incredibly capable developers and designers.”

While hardened fans of Japanese action games would hardly point to those two games as evidence of a studio’s suitability for making a new Devil May Cry, they meant Ninja Theory was exactly what Capcom was looking for: a modestly sized, technically proficient western studio with experience of melee combat systems. Even better, there were several fans of the DMC series at the studio, including Antoniades. Ninja Theory leapt at the chance but not, Antoniades explains, without some trepidation.

“The parameters for the project were daunting,” he says. “Capcom’s MT Framework [engine] was off the table, so we had to build everything from scratch ourselves. It also became very clear that Capcom didn’t just want a Devil May Cry 5, but a full-blown revamp of the gameplay, art style and story.” So while the bulk of the studio was putting the finishing touches on Enslaved, a small team began preproduction on Ninja Theory’s trickiest project to date.

One of that team was Rahni Tucker, an Australian who quit her job as a senior designer at THQ Brisbane simply to work for Ninja Theory. She packed up, said her goodbyes and made the 24-hour trip halfway around the planet with absolutely no idea what she would be working on when she arrived. “I had my meeting with HR on the first day,” she tells us, “and they said, ‘Well, you’re going to be working on Devil May Cry.’ I think I just said, ‘Oh my God’. It was pretty great.”

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

THQ Brisbane’s wheelhouse was licensed kids’ games, but Tucker had some melee systems experience from her work on Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine, a thirdperson shooter-brawler hybrid that began life in Brisbane but was finished in Canada by Relic Entertainment. Realising she needed more, she began her studies. “I went back and played the old Devil May Crys, Bayonetta, Street Fighter, gathering as much inspiration and influence as I could in that early preproduction stage,” she says. It paid off. Tucker would later become the lead combat designer on the project as a whole, working closely with Itsuno and his team to ensure Ninja Theory’s work stayed true to series tradition.

To a point, that is. Capcom knew that Devil May Cry’s sales had not historically been held back by the country in which it was made, and that simply handing the keys of Hideki Kamiya’s revered series to a western studio would not by itself create the surge in sales figures the publisher sought. “I think they wanted to make it little bit more accessible,” Tucker says. “Devil May Cry is about creativity with combos, [about] being able to get in there with all the different moves and weapons and juggle the enemy about. When you learn how to do it, you feel pretty awesome. That’s the key thing for me, and the thing we tried to bring to DmC for people who maybe don’t get to sit down for hundreds of hours to practice.”

Which isn’t to say that the plan was to dumb the game down. In the hands, Ninja Theory’s Dante retained the complexity and flexibility of games gone by, players juggling enemies ever higher into the air, and switching weapons on the fly mid-combo. The core input set – a jump, gunshot, and light and heavy attacks – remained, and many of Dante’s signature moves were brought over unchanged. Five games in, there was no sense in messing with a proven formula. Instead, Ninja Theory made some subtle tweaks to bring the flashier techniques within reach of beginners.

“A lot of the magic in Devil May Cry happens when you’re in the air – that’s been true for a long time,” Tucker says. “But getting into the air has, for novice players, been difficult in the past: you have to lock on, tilt the stick away [from the opponent] and press a button. That’s fine if you play games a lot, but if you’re fairly new to the series... people have struggled to ‘get’ those inputs. Trying to get some of those important moves onto a single button press was one of the first things we did to make it more accessible.”

So if you tap the heavy attack button in DmC, an opponent is launched into the air; keep it held down and Dante goes up with them. Tucker and team would next turn their attention to pause combos, which use the same string of inputs as regular combos but with a small break in between two button presses. Previously a question of getting a feel for the timing, now there would be a glint on the tip of Dante’s sword and a touch of rumble in the controller to signal when it was time to continue the assault. Simple, slight changes like this were exactly what Capcom desired: a way to make the game more accessible without compromising the intricacy of the systems at Devil May Cry’s core. A simplified launcher input was surely not going to upset the hardcore too much.

That job fell instead to Taini and the art team, although his first instinct was to do the opposite. “The first thing we tried was what we thought they wanted,” he says. “We were thinking about the classic Dante. Usually they do the same Dante with a different jacket, so we thought, ‘Maybe they want something like that.’ And we tried it. But when they saw it, they said they wanted us to put our own twist on it, to not think about the past, but to try something totally new. I remember they said, ‘Do something that we wouldn’t be able to do, otherwise we might as well do it ourselves.’”

So Taini rethought, and before long had come up with a design that Itsuno and Capcom fell in love with. He would turn his attention to the world next, steering DmC away from the foreboding, spiky Gothic architecture of previous games. He told the team in Japan that he wanted a more Romanesque style instead, something found across his home city of Genoa, Italy. “I didn’t want to make something that was classically Gothic,” he says. “There are already many games like that. I would talk to them about the different types of Gothic we have in Europe. In Genoa, there’s a lot of [Romanesque], and it’s more colourful, it’s a mix of styles. And they said, ‘Look, you’re European. You know much better than us what Gothic is, so if you want to use that, do it.’”

Basing Limbo on a real city was key, too. Capcom didn’t want Ninja Theory to refresh only the look and feel of the series, but its story. Both Heavenly Sword and Enslaved had been about relationships as well as action. Dante, however, had spent four games toiling largely alone in a demonic otherworld. Something had to give. “Devil May Cry games have often been set in the middle of nowhere – a big fight in a huge cathedral with nobody around,” Taini says. “I really needed an excuse for why there were no people around [when he fights]. That’s why we came up with the idea of Limbo: somewhere only Dante and demons can be, but it’s still a real city, with real people living there.” Grounding DmC in some sense of reality let Ninja Theory play around with convention. In one level, for example, Dante tries to save his accomplice, a medium called Kat, from an advancing SWAT team that he can hear but not see. He battles enemies in closed-off arenas while the SWAT forces break down the doors around him, allowing him to press deeper into the bunker where Kat is hiding.

While Capcom Japan kept a close eye on Ninja Theory’s work on DmC’s characters, story and world, its greatest focus was, naturally, on the game’s combat. Itsuno and other key personnel would visit the studio in Cambridge every few months to check in on its progress, Ninja Theory staff would often make the trip out to Japan, and in between those times there would be regular video conferences and daily email updates. All that communication helped to unify the two companies, despite a fundamental split between their approaches to game development: Ninja Theory liked to start with the visual design, and Capcom with the mechanics. Modestly, Itsuno admits he learned a lot from the collaboration; Tucker believes she picked up an awful lot more.

“I learnt so much,” she says. “Itsuno would speak philosophically about how he approaches combat and enemy design. They build most of the player’s set of actions first, and then think about the things they can build to allow players to exploit particular elements of the system they’ve designed. They really put the emphasis of the baddie design back onto the player’s actions. It’s kind of obvious, but just the way that he spoke about it was inspiring, and it made a lot of sense to me.”

As the project drew closer to completion, Capcom’s attention to the finer details – frame timings, cancel windows, animations – increased. The game launched in January 2013 and was well received critically, but it would not do as well commercially, despite a strong start that saw it hit number one in the charts in the US, Europe and Japan simultaneously. Antoniades says sales were “ultimately disappointing”.

Capcom’s last official update on the game’s performance came in June 2014, when worldwide sales totalled 1.6 million, some way short of the two million copies that Capcom had initially planned to ship to retailers in the game’s first six months on shelves. Within three months of DmC’s release, Capcom had announced an end to cross-continental collaboration and told the world that it would be bringing back in-house development of both existing and new IP.

Yet while the official figures may not flatter, the tone of those angry forum threads gradually warmed in the weeks and months following release. Check in on them now and the invective that surrounded the announcement is all but gone, replaced instead by fond recollections of a game that brought Dante’s flashy badassery within slightly easier reach. Unluckily for Capcom and Ninja Theory, many of those players found the game for free through PlayStation Plus, rather than on a store shelf. The PS4 and Xbox One Definitive Edition, released on March 10, may yet reverse the game’s fortunes, but in the meantime there are no regrets expressed over a healthy collaboration project that deserved to do better at retail.

“With every project you work on, you learn so much,” Tucker says. “And when you’re working so closely with a company that has so much experience with a genre that Ninja Theory is so interested in, you do learn a lot. We’ve definitely got better at combat. I know I have.” The studio’s greater experience is currently powering development of Hellblade. Tucker, however, is working on another project, one in its early stages and shrouded in secrecy. Expect another Ninja Theory staple – that blend of story, character and combat – but this time with a less controversial haircut.

Read more from Edge here. Or take advantage of our subscription offers for print and digital editions.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.