33 years later, Alone in the Dark still deserves recognition as the survival horror that bridged the gap between Cthulhu and Resident Evil

Feature | Back in 1992, Alone in the Dark changed the face of horror forever

Had Alone In The Dark never existed, there would have been no Resident Evil – at least, not in the form that we know it. Capcom's survival horror title was originally envisaged as a spiritual successor to the 1989 NES RPG Sweet Home, which was based on the Japanese horror film of the same name. In the end, very little of that game's DNA made it into Resident Evil, save for the mansion setting. Instead, director Shinji Mikami played Alone In The Dark, and was captivated by its expressive fixed-camera viewpoints. If it hadn't been for Mikami playing that game, he told Le Monde in 2014, "Resident Evil would probably have become a first-person shooter"

In addition to those horror-movie-inspired camera angles, Mikami's game apes Infogrames' groundbreaking 1992 title in other ways. Both feature a choice of two protagonists, with scarce ammo and limited inventory space. Arcane puzzles abound. Alone In The Dark even had creatures crashing through windows, long before zombie dogs showed up in Resident Evil.

The Big Preview Horror Special hub has even more exclusive access to the biggest games in the genre on the horizon, and deep dives into iconic classics!

Infogrames had likewise begun with a source material from which it would soon veer away. The French studio acquired the licence to Chaosium's Call Of Cthulhu tabletop RPG, and the game first reared its head under the same name, appended with the subtitle Doom Of Derceto. However, by the time of its release, the licence had been revoked and the name changed. A few elements of that setting survive, but Alone In The Dark is as influenced by the films of George Romero and Dario Argento as Lovecraft's writing. The plot also borrows from Edgar Allen Poe's The Fall Of The House Of Usher, in which the protagonist is summoned by letter to a mysterious house that appears to have a life of its own.

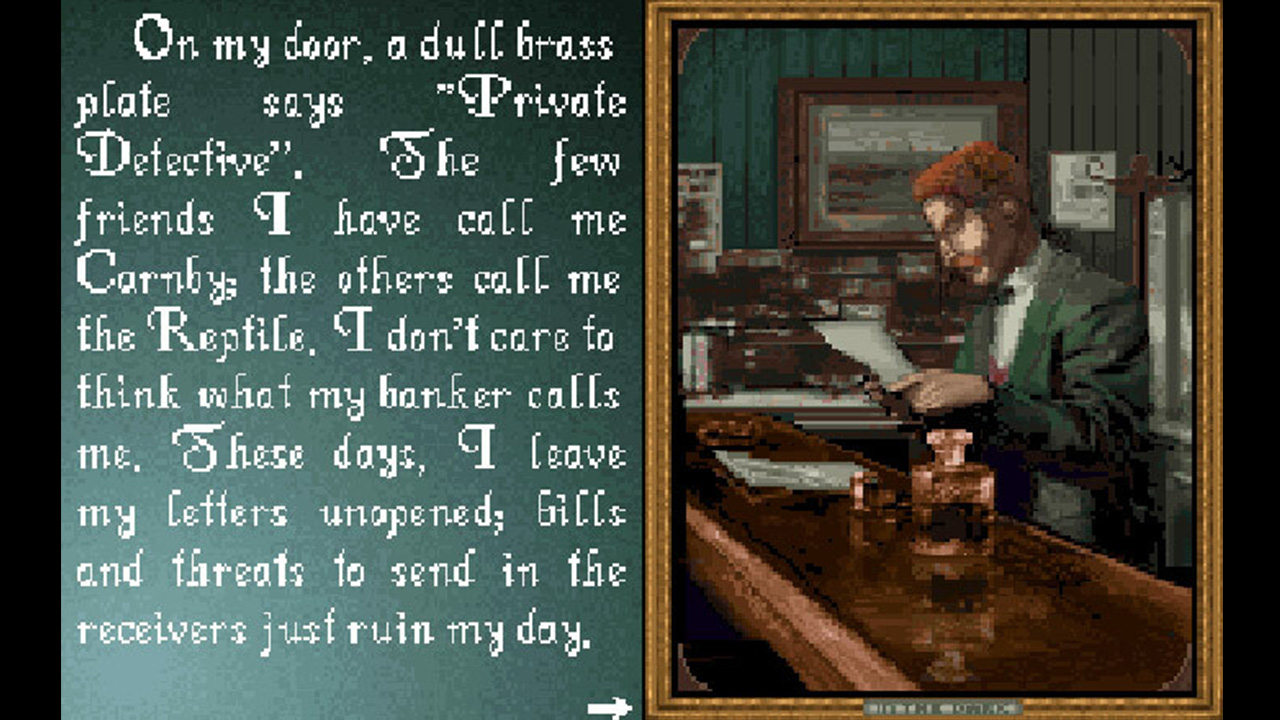

And indeed, it's a letter that prompts Emily Hartwood and Edward Carnby to investigate the Derceto mansion, the site of Jeremy Hartwood's death by hanging in 1924. Emily is driven to find clues about her uncle's suicide; Edward, meanwhile, is a private investigator who has been sent to retrieve a piano for an antique dealer. You can choose either character at the start, although the game plays out exactly the same way no matter who you pick.

The plot is told through books and notes, gradually telling the story of a pirate called Ezechiel Pregzt who has extended his life through the practice of dark arts, and who intended to use Jeremy Hartwood's body as his next host. Dying prompts a cutscene in which Emily or Edward becomes the next host instead, unleashing supernatural horrors on the world.

Regardless of how they look, though, such monsters remain terrifying.

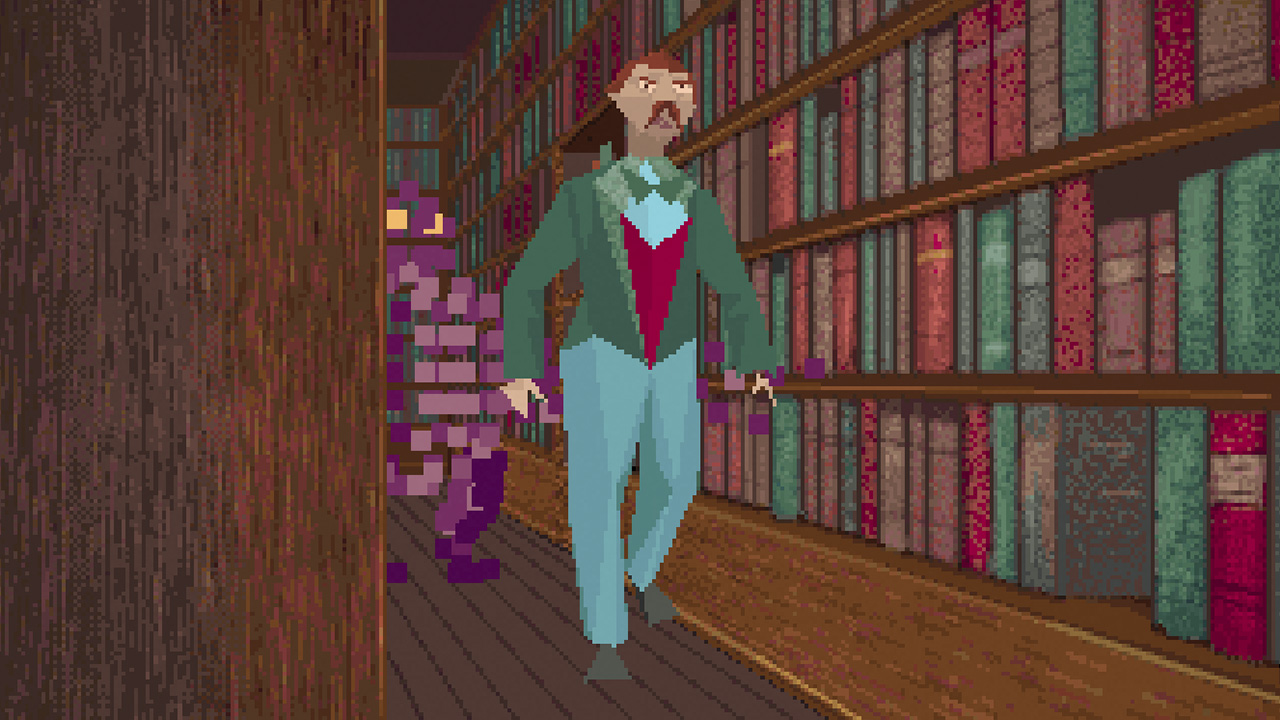

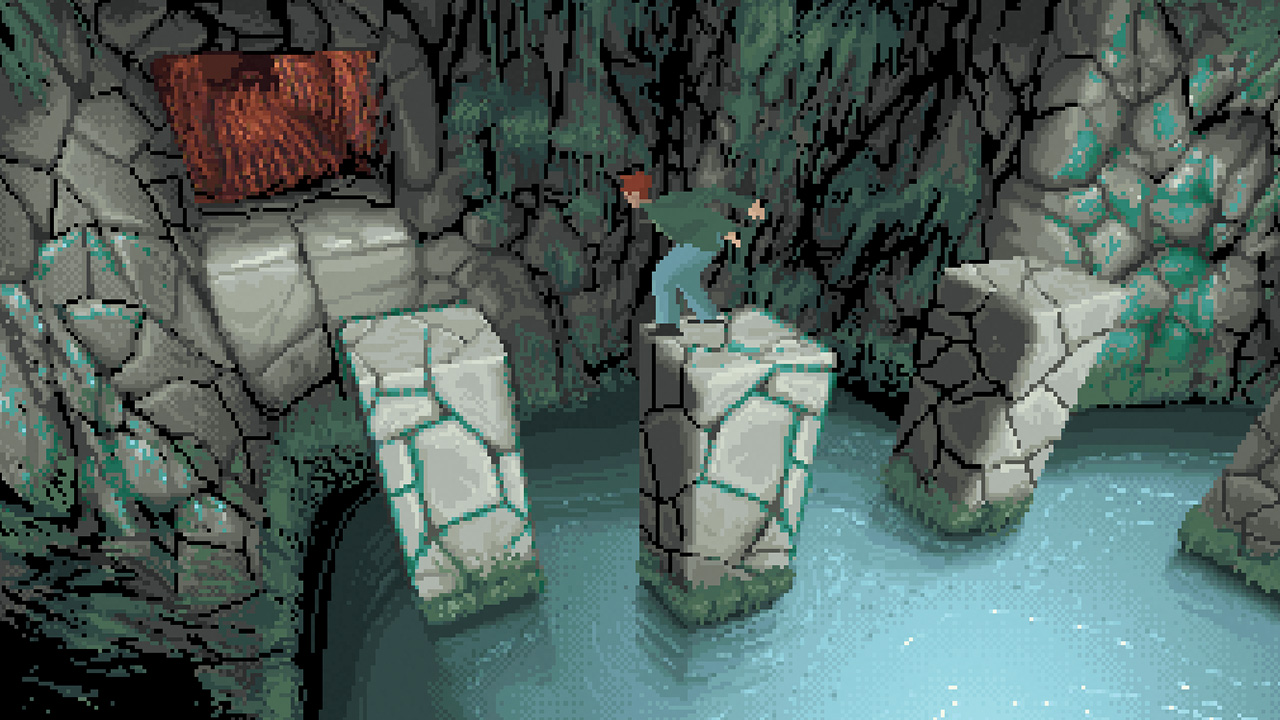

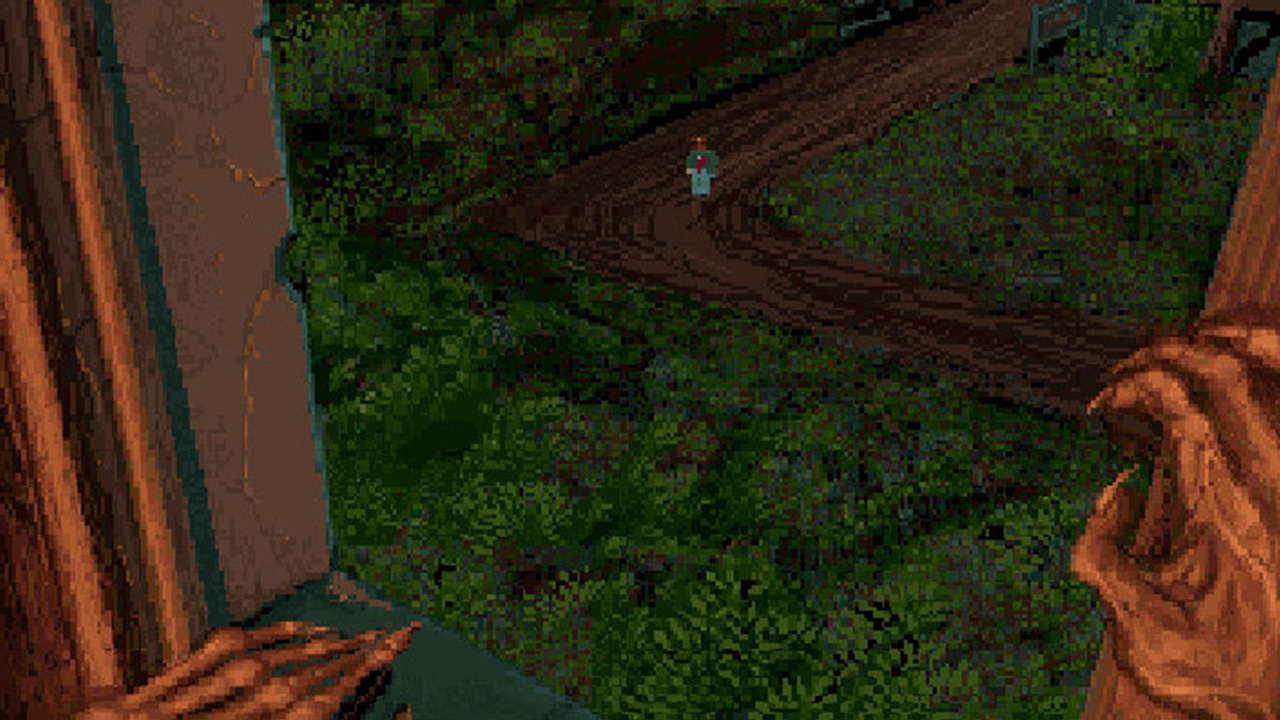

Looking back now, it's hard to believe Alone In The Dark once represented the bleeding edge of graphics technology. Holding its blocky, rudimentary polygons up next to Resident Evil – released just four years later – it's a stark reminder of just how quickly the state of the art was moving for videogames in the early '90s. Emily and Edward are represented with crudely rendered faces and angular bodies; the dangers of Derceto Manor fare worse still. The bird monster which stomps through the attic early in the game looks as though its concept art might have been a child's drawing of an angry chick, complete with triangular pointed teeth.

Regardless of how they look, though, such monsters remain terrifying, thanks in no small part to the limited tools you have for fending them off. Both health and ammunition are in short supply: only two guns exist in the entire game, with a total of two dozen bullets between them, and there are just a couple of first-aid kits to last you the entire adventure. Compounding this, the game has no qualms about killing you with little or no notice. Right near the start, the floor gives way in a hall, plunging Emily/Edward to their demise. Opening the front door of the mansion reveals a giant tentacled beast that swiftly ingests you. Touching one of the mansion's ghosts means instant death. Even reading the wrong book can see you shuffling off this mortal coil.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine 393. For more in-depth features and interviews diving deep into the gaming industry delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

It's malicious and unfair, the kind of trial-and-error activity that necessitates near-constant manual saving, and an approach that would be unlikely to survive the playtesting phase in a modern game. And yet it works precisely as intended. Every step in Alone In The Dark is a tentative one, as you warily explore the mansion, never knowing what horrors might lurk behind each door. The audio helps to ramp up the tension, the odd piercing shriek or gurgling moan stopping you in your tracks.

It's easy to understand why games would become kinder to players over time, their tutorials and autosaves opening the medium to a wider audience. Playing Alone In The Dark, it's difficult to shake the feeling that it hates you, and will do everything it can to force you to give up. Of course, that can be compelling in its own way. Progress that must be hard won is all the sweeter for it, as FromSoftware knows well. As other developers chase the singular pleasures of the Soulslike, this lends Alone In The Dark an edge of counterintuitive modernity.

Alone In The Dark is also deliciously weird, in a way that few games achieve. One room features a haunted cigar in an ashtray, which quickly fills the room with damaging smoke. The final boss is a tree. The game delights in wrong-footing you, presenting the unexpected, offering a surprise behind every door. Indeed, many of the creatures you face are unique. There are a handful of the zombies that would become Resi's bread and butter, but that series' occasional shark or carnivorous plant can't hold a candle to Alone In The Dark for sheer strangeness.

A swashbuckling pirate ghoul haunts one hallway of the mansion; a giant worm waits in the darkness of the cellar; and at one point you encounter a malicious squid-like creature in a bath. And then there's the 'Vagabond', an interdimensional predator surely left over from the game's Lovecraftian roots – though in practice it more resembles a Mr Men character made of purple jelly. It's enough to ensure that a shortage of ammo isn't the only thing that makes these encounters memorable.

It's possible, even easy, to miss vital clues and wander for hours in confusion.

The puzzles are also suitably oblique, of the kind that require you to pay attention with a notebook and pen to hand. At one point you encounter a ballroom full of stationary ghosts locked in a dancing embrace, a key lying on the mantelpiece just beyond them. It becomes clear that you need to place a gramophone nearby and play music to make them dance away from the prize, but there are records scattered all over the mansion, and the ghosts only dance to one particular tune, the identity of which is written in a single book. It's possible, even easy, to miss vital clues and wander for hours in confusion – another tendency that's been tidied away by many modern games. Yet titles such as Tunic have begun to rediscover that magic, content to let you wander half-lost on the cusp of understanding, solutions tantalisingly out of reach. Again, there's merit to frustration.

One aspect that's harder to explain as anything other than simply dated, however, is the keyboard-only 'tank' control method, which sees Edward/Emily shuffle along at a glacially slow pace. It's possible to run – at what other games might consider walking speed – but this requires a double tap of the Up key with all the precision timing of a Street Fighter combo. It's particularly infuriating at times when speed is of the essence, such as when fleeing the aforementioned giant worm.

The cascading menus are similarly frustrating. Even something as simple as searching a cupboard involves tapping the Enter key, selecting 'Actions', then 'Open/Search', and finally holding down the Space bar near the cupboard in question. Fighting necessitates a similar flurry of menu navigation, after which you have to hold down the Space bar while pressing the arrow keys to unleash punches or kicks. But the windup animation for your attacks is so sluggish that it's all too easy to be backed into a corner by a monster whose attacks are too quick to counter with your ponderous punches, necessitating yet another restart.

Sometimes, even a restart won't cut it. Your lamp can run out of oil if you use it for too long, making it impossible to navigate a dark maze towards the end. Elsewhere, you cross a bridge that falls away behind you, closing off any possibility of backtracking. If certain key items aren't in your possession at this point, such as a talisman found in the library or the key from the ballroom, then the game is rendered unwinnable, forcing you to restart from a save point before the bridge – provided, that is, you thought to make one. This is a harsh game, then, in which progress is only achievable through repeated failure, unafraid to set you back almost as often as it allows you to edge forward. In that it is, perhaps, an ideal representation of Lovecraft's bleakly unforgiving universe, and an unlikely template for the future.

If there remains only a homoeopathic trace of its trademark eccentricity and malice in recent Resident Evil games, which have, over the years, grown closer to the first-person shooter Mikami originally envisaged, then those traits have certainly been picked up elsewhere. Now, Alone In The Dark is about to get its own remake, boasting a starry cast (Jodie Comer as Emily, David Harbour as Edward) and a considerably higher polygon count. We'll soon find out whether it follows the Resi remakes' tendencies towards action and away from old-fashioned oddities. We're hoping, though, that the unsettling weirdness wins out once more.

Take a look at our best horror games ranking for more!

Lewis Packwood loves video games. He loves video games so much he has dedicated a lot of his life to writing about them, for publications like GamesRadar+, PC Gamer, Kotaku UK, Retro Gamer, Edge magazine, and others. He does have other interests too though, such as covering technology and film, and he still finds the time to copy-edit science journals and books. And host podcasts… Listen, Lewis is one busy freelance journalist!

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.