Remembering the iconic Blair Witch Project

Some joker dubbed it “The Blair Hype Project” back in 1999, as if a clever marketing campaign made the film’s success a sure thing. As an index of how brilliantly bold The Blair Witch Project was, however, keep this in mind: it could have just as easily ended badly…

Just as its three film students headed into knotted woods in October 1994, so the movie’s creators mapped gnarled terrain. Shooting documentary-style, they conjured up an unprecedented hit of first-person fear. Their tools of terror? Twigs, off-screen insinuation, a recurring log and some thing/person/crack-squirrel/whatever leaving shit all over their shit. The movie was low-cost horror as high-risk experimentalism – it could have died on the floor. It could have ended badly in other ways, too. If you haven’t seen the film, go stand in the corner and come back for the next paragraph. You gone? Good. Here goes…

Mike Williams, the sound guy in Heather Donahue’s student-film trio, has been lured into an old dark house by the screams of his friend Josh Leonard. The walls are scarred with small handprints and symbols. When we join Mike in the cellar… he’s staring into the corner of the room – but he’s not peeing. It’s freakin’ creepy. Then you recall something from earlier in the film about how a local child killer made kids stare at the corner while he got to work… “Holy shit!” You said it.

The film’s distributors, Artisan, weren’t sure about this teasing closing gambit. After a test screening, they asked co-creators Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez to shoot something less subliminal. Dutifully, Mike got trussed up to a bundle of twigs and hung from a noose. Like we said, it could have ended badly. “We always felt the original ending was the one to go with,” recalls Myrick. “Artisan felt it was a bit ambiguous and we were broke, so they gave us a bunch of money – more than the whole film cost – to shoot two alternate endings. We didn’t like either of them. So we phoned Artisan and said, ‘We strongly believe that the original ending was the best.’ I’ll never forget the response. They sighed and said, ‘Well, okay, we’ll go with your ending. But we think it’s gonna cost us millions at the box office.’” It didn’t. Back when films were yakked about more than blogged about, it was the most talked-about flick of its year, next to the lesser and considerably more-hyped The Phantom Menace. But hype alone didn’t sell Blair Witch. This was a film that trawled horror’s roots with chutzpah and daring. That, plus a fundamental understanding of what creeps us out…

In the early to mid ’90s, Hollywood set out to make horror from old rope. Dracula got dug up, Frankenstein sewn up. Most of these films were seen once and never again. A few years on, some footage was found…

Stretching back pre-Scream, a crew of University Of Central Florida film students were planting scare-seeds in the woods. With producers Gregg Hale, Robin Cowie and Michael Monello, Myrick and Sánchez set up Haxan Films and earned some spurs on production work, shorts, TV tat and Planet Hollywood promo material. They also shot a short about a witch, called Fortune. These guys dug horror movies, but not the genre flicks of the time. “Most quote-unquote artists I know are looking to do something different,” Myrick reckons. “I don’t know how premeditated it was but we were disenchanted with the state of horror films in general. At the time it was all about Americanised, big-budget fare that ultimately didn’t really scare us.”

Sánchez agrees. “We set out to make something scary. We didn’t see that happening anywhere else. Horror was in a serious lull so we went back to what scared us as kids in the ’70s and early ’80s. Films like The Shining and The Exorcist were what we wanted to make, but we knew they were way out of our league.”

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

A fascination with what made fear fly led them to root it in reality. That and a few monetary constraints… “We grew up with television shows and movies like In Search Of, which was a UFO-type documentary narrated by Leonard Nimoy,” says Myrick. “Plus a limited-release film called The Legend Of Boggy Creek. They were shot in a documentary style and portrayed as legitimate. It’s really not too difficult to convince people that something is real if you focus and make sure the details are done right. I think on one level Blair Witch speaks to how people can be duped.”

“The idea that all this stuff they were showing was happening brought a dimension that narrative films couldn’t touch,” says Sánchez. “So we set out to make a documentary film that could be cheap and would scare the fuck out of us.”

To get the approach right, Haxan turned to a secret weapon: off-screen space. “Part of the problem with some mockumentaries is that directors feel compelled to show everything,” Myrick says. “But whenever a camera or a plot-point is conveniently placed, you feel like you’re watching something premeditated. That’s exactly what we wanted to avoid.” An illustrative contrast is another ’99 horror, Jan De Bont’s remake of The Haunting. De Bont splashed his bloated budget all over the screen. Myrick and Sánchez scared you with stuff you had to squint to see but still couldn’t quite make out. Google your way through web thickets and you’ll find Blair Witch fans debating what’s actually in the final frames. Is that a face? A hand? A map? No one gives a rat’s about De Bont’s debacle…

"We stepped back as directors while keeping our actors on a narrative path."

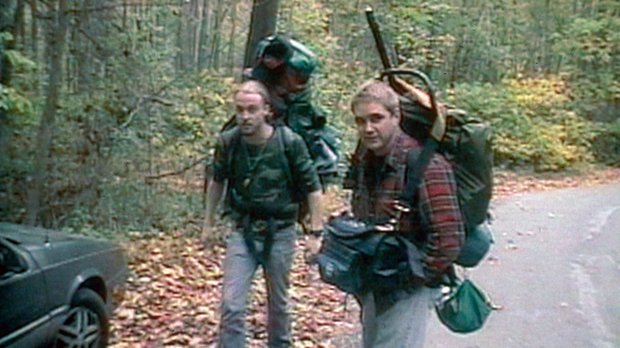

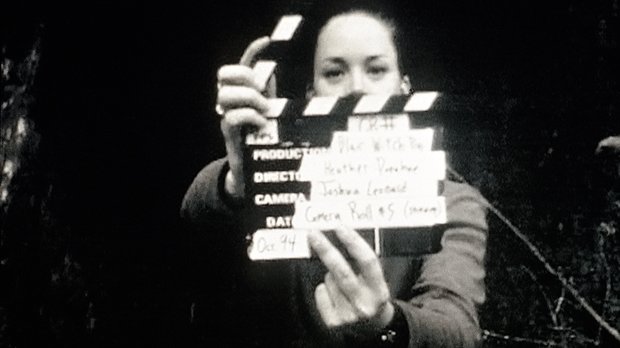

The Blair Witch boys found an ingenious way of spreading the fear. They would send the trio of actors into the woods with a camera, a few supplies and a basic narrative for company, feed them plot points on a need-to-know basis and let them improvise. The film would emerge from first-person camerawork (the black-and-white 16mm footage shot for the students’ doc and Heather’s Hi8 video footage) and reactions that at least breathed down the neck of authenticity. “The theory was,” says Myrick, “let’s construct a narrative that our actors can follow but the way in which we shoot it, the execution, should be as much like a documentary as possible. So we stepped back as directors while keeping our actors on a narrative path.”

Unsurprisingly, the cast felt a bit anxious. “Especially Heather, being a girl and asked to live in the woods for eight days with a film crew she doesn’t know!” Myrick recalls. “Heather told us quite frankly that she was a little concerned and her parents definitely were. But we made it very clear that safety was our number-one concern, y’know, we’re not a bunch of goofballs trying to shoot a slasher film…”

Was she really scared enough to come to the shoot armed? “Yeah, she brought a hunting knife.” Myrick laughs. “And I don’t blame her!” Donahue had only been camping once before. Trial by fire, anyone?

After a crash course in camera and sound, the cast were led from Burkittsville to Maryland’s Seneca Creek State Park, where they were tracked via a military-satellite Global Positioning System. The crew left notes for guidance and kept tabs on the dailies. Gregg Hale, too, had previously undertaken a Special Forces training programme called SERE (Survival Evasion Resistance And Escape), the lessons of which proved useful in using suggestion to put the willies up the cast. From there, the shit hit the fan…

“They had no idea of what was going to happen,” Sánchez says. “It was like an eight-day play and they inhabited the world of the characters 24 hours a day. You get things that way that you really can’t get any other way. We basically played the Blair Witch, so any time you hear something it was us messing with them. Mostly just running around at all hours of the night while they tried to sleep…”

“We gave them enough information to know what to do,” adds Myrick. “They knew something would happen every night and that they had to run out of the tent. The mandate we gave them was just to shoot everything.” After all the shrieks, howls, rock graves and “blue jelly shit” all over cast member Josh’s equipment, nothing left them more in the dark than a bundle of ambiguous Josh-ness left as a gift. What was in there? “Something nasty and organic and bloody,” according to Sánchez. “Gregg got his hands on some teeth from the local dentist,” Myrick laughs. “We didn’t need to tell Heather what was in it. They heard someone screaming the night before, so it’s pretty easy to connect the dots. You just have her open it up and see bloody teeth… It’s just not good!”

Originally, there was to be more to the film than Heather’s crew’s slow demise. Their footage was to be Phase I, with Phase II as background mock-doc detail. Myrick and Sánchez wanted to cut material about the witchy case of Elly Kedward in 1785, the 19th Century Blair Witch Cult text and ’40s child-killer Rustin Parr into the film. But they realised the core trio’s footage stood on its own and that this extra material could work as a fully realised world surrounding the central narrative – hence the DVD extras and the website.

Blairwitch.com’s ground-breaking viral marketing was conjured after indie guru John Pierson saw Myrick and Sánchez’s initial eight-minute trailer-cum-promo reel, wondered if it was real and screened it on his cable show, Split Screen. “That got the ball rolling,” says Myrick. “His show generated so much interest on his website that it gave us the impetus to steer some of that action on to our website and our cause, which was to promote the movie.”

From that trailer reel, Haxan secured the moolah to make the film. At Sundance in January 1999, Artisan bought it for $1.2m before arranging college screenings to generate word of mouth and, on April Fool’s Day, relaunching the website with complementary police reports and back-story material. Ingenious as this campaign was though, no one could have predicted that the film’s July ’99 US opening would see an initial 27-screen release leap to 1,000 and then 2,000 screens. Or that a $40,000 budget would reap around $140m in the US alone.

“Ed and I thought we had a cool movie,” says Myrick. “Something that could be a neat indie cult within reasonable expectations. We sold to Artisan, who had released Pi the year before, which did $3m at the box office. We thought if we could do even $10m we’d be on cloud nine. We even made a wager with Artisan. Ed and I and the guys were into foosball [table football] and we said, ‘If we make $10m, you guys have to buy us a competition-grade foosball table.’ On the weekend of release, we get a knock on our door and outside there’s a brand-new foosball table…”

Why did it hit a nerve? The room left for interpretation surely helped. By keeping the content spare, Blair Witch opened itself up to numerous readings. Was it a millennial-anxiety film? An allegory for American over-confidence, in which cocky kids abandon their comfort zone only to find they’re in too deep? Or?

“We were fatigued with big-budget films and on the cusp of reality programming and the internet age. That confluence of events just intersected,” reckons Myrick. But Sánchez has a different theory. “On a basic level, for some reason, people love to see other people suffer,” he says. “Blair Witch was basically a snuff film that was safe to watch because it wasn’t real.” But, as both agree, one core fact remains: it’s scary as hell.

“It scared the hell out of me at times during the editing,” says Sánchez. “When I was editing the house scene at the end by myself late one night at our offices, I had to turn the computer off and go home because of it. And I had directed that shit!” No movie since The Blair Witch Project has repeated its impact, with the possible exception of Paranormal Activity – a child of Blair Witch. Cloverfield may have mimicked the form but couldn’t reach Blair Witch’s sky-scraping returns. Was it simply too premeditated and risk-light to match Myrick and Sánchez’s high-wire act?

“I love Cloverfield for its approach,” says Myrick, “and the execution was top-notch. My problem was that I felt like I was watching actors. And that’s where it takes me out. Rather than a group of good-looking actors from LA, imagine if it was a plumbers’ convention we were following! One of the reasons Blair worked so well was that the actors looked like real people. Heather could well be in your neighbourhood. Michael and Josh look like dudes you hang out with or see down the Kwik Stop.”

Myrick agrees that the Blair Witch sequel, Book Of Shadows, fell foul of the same problem: “It was made for the wrong reasons and it undermined the mythology of the movie,” he says. But does this ages-old story have to end so badly? Could Haxan return to the woods and the miasma of mud, myth and bad magic again?“I wouldn’t mind doing it, quite frankly,” says Myrick. “Ed and I’ve always wanted to get back together and collaborate on something. And if it’s on a third Blair Witch, then maybe. A new generation of filmgoers are out there and it may be something worthwhile. I’m certainly open to that possibility.” Fingers and twigs crossed, then. This grim fairytale might not be over yet.

Click here for more excellent Total Film articles. Or maybe you want to take advantage of some great offers on magazine subscriptions? You can find them here.

The Total Film team are made up of the finest minds in all of film journalism. They are: Editor Jane Crowther, Deputy Editor Matt Maytum, Reviews Ed Matthew Leyland, News Editor Jordan Farley, and Online Editor Emily Murray. Expect exclusive news, reviews, features, and more from the team behind the smarter movie magazine.