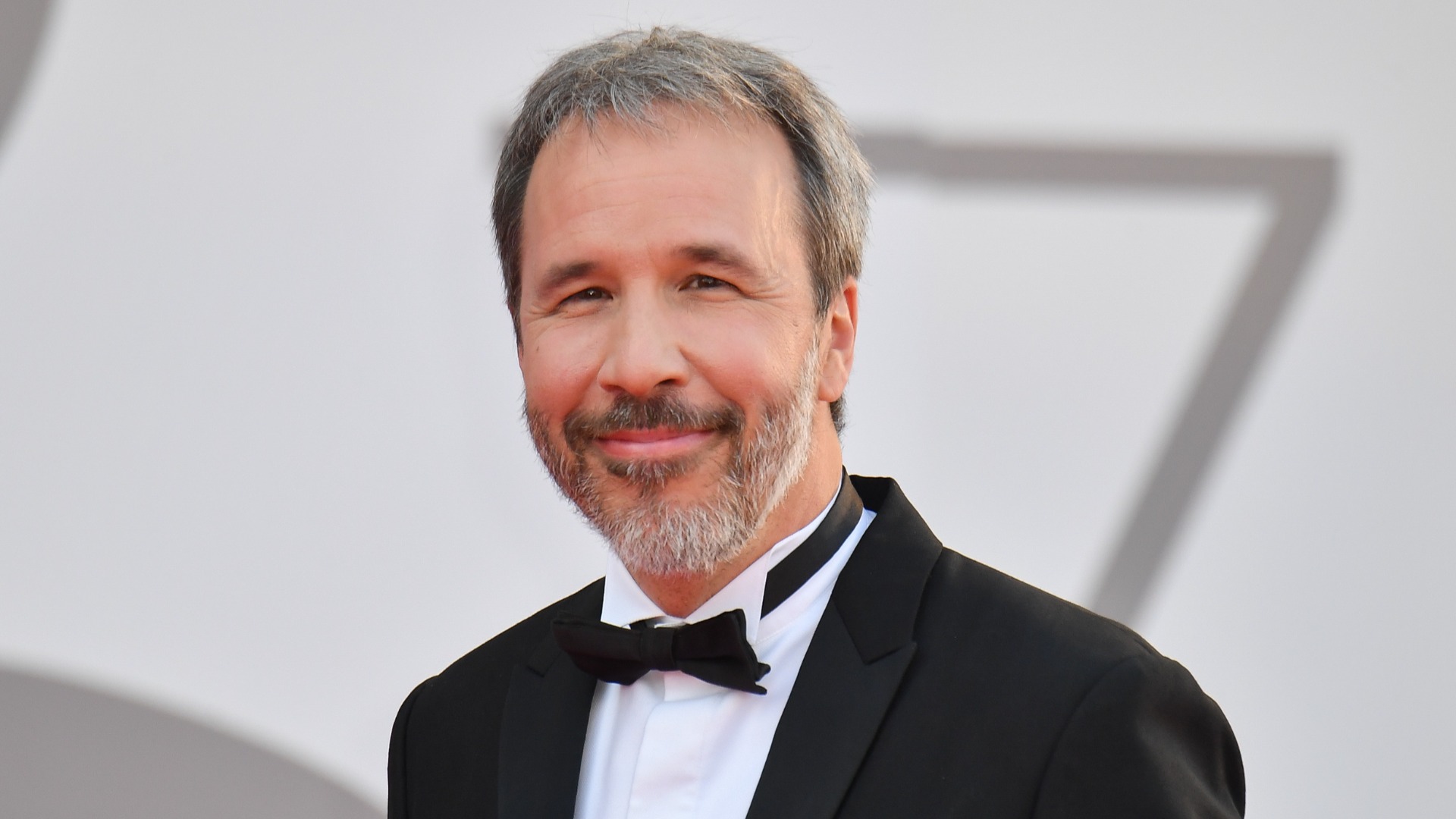

Dune: Denis Villeneuve talks books, Part Two, and the future of cinema

GamesRadar+ and Total Film sat down with Denis Villeneuve to talk about his adaptation of Dune, what was cut from the book, and his fears about the future of the mid-budget movie

Denis Villeneuve's Dune looks set to top more than a few "best movies of 2021" lists. The grand scale of the director's adaptation of Frank Herbert's seminal novel is simply astonishing – and well worth a cinema trip (if you're in the position to visit the multiplex safely).

Villeneuve has been building to Dune for a long time. The filmmaker has gone from working on low-budget Canadian features (such as Maelström, which is narrated by a talking fish) to mid-budget hits such as the thrilling Sicario, the Hugh Jackman-starring Prisoners, and the Best Picture-nominated Arrival. Following those successes, he took on a sequel to one of the most beloved sci-fi movies of all time, Blade Runner. The man loves a challenge.

Dune marks Villeneuve's biggest movie to date – and, unlike David Lynch's attempt at the heralded sci-fi text, the new adaptation is just "Part One" of a greater story. GamesRadar+ and Total Film sat down with Villeneuve to discuss the movie, its themes, visuals, and the potential sequel (still not confirmed, but looking likely). We also briefly touched on the future of cinema with regards to the mid-budget movie arena. Here's our Q&A, edited for length and clarity.

GR+: You tackled Dune following Blade Runner 2049. On a thematic level, both tackle the "Chosen One" narrative in different ways, with Blade Runner’s K being a misleading "Chosen One" and Dune’s Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet), at least in this movie, being a Messianic figure. Do you see the two as companion pieces? What interests you about the "Chosen One" narrative?

Villeneuve: In fact, I would say that the "Chosen One" narrative is not interesting to me. What is interesting is that both projects are revisiting this notion, but from a different angle than the traditional Messianic figure. In the case of Blade Runner, as you said, it's a mislead. And in the case of Dune, Paul’s character is reluctant to be part of it. It's a cynical take on the Messianic figure, where someone feels that he is just a product of religious manipulation. He has a critical view about that and doesn't embrace the idea. He almost doesn't believe in it. Of course, he has the burden of heritage on his shoulder but he is afraid of using that power, he’s questioning that power that comes from colonialist forces. He’s afraid of being himself – of being an instrument of colonialism. So, it’s very critical of that idea.

Why do you think you're interested in criticizing that narrative?

First of all, it's a trope, and it's something that in the book, Dune, Frank Herbert wrote the book as a warning of the Messianic figure – that someone would be chosen among others to lead and become a charismatic Messianic figure. Dune is a warning about that.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Dune begins with the promise of this being "Part One", which implies "Part Two" is incoming. While that’s not confirmed to be in production yet, was there any discussion about simply calling the movie "Dune" without the "Part One"?

For me it was necessary. It was always meant to be a two-part movie and it was always meant to have "Part One" at the beginning because I feel like it would be misleading and dishonest to pretend that it's the whole story being told in a single movie. I wanted the audience to understand, right from the start, that they were about to see the first part of a bigger story.

The international box office is looking promising, but is there any part of you that wishes you had filmed both parts back-to-back?

That's what my first idea was, to shoot them together. Then, like the Lord of the Rings, release one after the other, a year apart. But that was too expensive. And frankly, I'm grateful that it didn't happen as I wished because I would have been too exhausted. During the first one, I needed all my stamina – I needed all my energy. It would have been too much to do both back-to-back shooting in the desert. I learned so much [while filming] Part One that, if ever it happens, I can make a better movie with Part Two. And I'm grateful that it happened in this way. I prefer to be in this position right now than having shot both movies back-to-back and having regrets because I was too tired.

What’s so stunning about Part One is that the visuals are a mix of being grounded and having a big sci-fi feel – you have bagpipes and giant sandworms in one movie. How did you approach keeping things grounded and without going too Star Wars-y?

We had time to do it. I said to the team at the beginning that we should inspire ourselves exclusively from the book. I wanted the movie to be as close as possible to the vision I had when I read the book at 13 years old, and I wanted the fans of the book to, as much as possible, recognize the description, the atmospheres, the world that has been depicted in the book. I wanted to be faithful to Frank Herbert as much as possible. To go back to the original images that I had as a kid, they were these uncorrupted images. That helped a lot to try to bring something kind of fresh to the screen. Of course, it required a lot of meditation and work because there had been a lot of sci-fi movies made in the past decade. The Star Wars series is a huge elephant in the room. The way Star Wars approaches design is so beautiful. So we have to find our own identity. It took us time – time and a lot of thinking.

Some of the spaceship shots reminded me of 2001: A Space Odyssey. What were the other foundational building blocks you used?

The foundations were the book and nature. I wanted the technology to be inspired by the environments in the book. For example, the helicopter, I wanted a machine that you believe can endure the harsh conditions of the desert. That is a machine that’s believable and answers to the laws of gravity and laws of physics. It had to feel realistic – to feel grounded in some reality and away from fantasy. It felt closer to the spirit of the book. I made references to movies I love and paid homage to directors I love. But the design was based on the book.

Speaking of the book – how did you go about deciding which elements to cut and which to keep? For instance, Duke Leto (Oscar Isaac) feels that Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) may be a traitor in the novel, but that didn’t transpire on screen.

I decided to focus the entire adaptation on Paul's journey. There are a lot of characters in the book, of course, but Paul is the central figure. I tried to stay with his perspective as much as possible and then to bring into the foreground his relationship with his mother, which is at the very epicenter of this story. I love the character of Lady Jessica and I wanted her dramatic arc to be prominent in the story. From there, I was making a lot of choices in order to focus the story on both characters. I had to use broader strokes and it would have been too long of a movie if I hadn’t focussed on the main storyline, avoiding subplots.

There’s one scene, in particular, that’s a fan favorite and missing from the movie – a dinner scene where Paul is infantilized by a visiting banker. With that specific scene being about Paul, I’m wondering how far you took that forward? Was it shot?

That scene was written. It was never shot. It's a scene that I decided to remove because, in the structure of the movie, it was not bringing something new to the story and the story that I was trying to tell. It was creating problems with the momentum. I was trying to create a movie that will feel as visceral as possible and I experienced the book when I was 13 years old.

I have one final question and it takes in a few of your films. You've gone from making these mid-level, $40 million budget movies – Sicario, Arrival, Prisoners – to big-budget franchises. Looking on Hollywood today, those mid-level movies wouldn't necessarily, from my perspective, be made by the classic film studios. You're more likely looking at them being released on streaming services. What's your take on the future of the mid-level movie? Do you think we're seeing enough of them?

I remember when I did Prisoners, people around me were saying "People don't make movies like that anymore." It's the low budget or super big budget, there's no middle. And I had the chance to evolve in that medium space for a few years, which became more and more a rarity. And I think it's a problem. I think that the future of cinema relies on the creativity of lower budgets. The main battle will be to make sure that these movies have access to the screen. The big franchise movies will go on the big screen but I do not have the answer yet. I believe in the future of cinema on the big screen and I think it's very important that all kind of cinema has access to the theatres, not just on the major Hollywood movies. It's not a crisis that suddenly happened with this pandemic. It's been a while, with the theatre becoming less and less accessible for smaller movies. And I think it's a problem, frankly.

Dune is in UK cinemas from October 21 and US theatres from October 22. Dune is also available on HBO Max in certain territories. For more on sandworms, check out our guide to the Dune books, movies, and TV shows.

Jack Shepherd is the former Senior Entertainment Editor of GamesRadar. Jack used to work at The Independent as a general culture writer before specializing in TV and film for the likes of GR+, Total Film, SFX, and others. You can now find Jack working as a freelance journalist and editor.