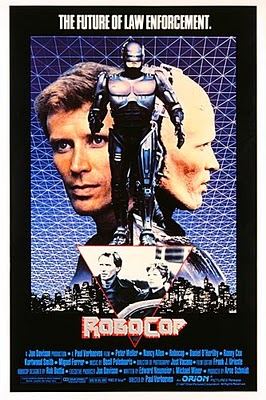

The Making Of RoboCop - Extended Cut

None

The definitive history of the SF classic!

As an SFX website exclusive, here's a massively extended version of Jorge Khoury's marvelous Making Of RoboCop feature that originally ran in SFX 217. Enjoy, citizens!

RoboCop isn’t just one of science fiction’s greatest films. It’s a lasting game-changer that became one of the most influential films to emerge from ‘80s cinema, radically combining social commentary, satirical comedy and blood-soaked action. Under Paul Verhoeven’s bold direction, the screenplay by writers Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner was unleashed as a beautifully layered film that never pulled its punches. With a a cast that included Peter Weller as the titular cyborg and Miguel Ferrer as his creator, audiences became enthralled with RoboCop’s quest for justice and identity. Now the cast and crew remember the story behind the creation of the chrome-plated “American Jesus”…

CONCEPTION

ED NEUMEIER : I was a story analyst working for Columbia Pictures in about 1983, and most story analysts want to do anything else but be a story analyst. I had this interest in writing an action script. At that time, people were always telling you you shouldn’t write science fiction because it was too expensive, but I still was very interested in science fiction. Star Wars came out when I was in college, and I was a big fan of the Clint Eastwood action pictures of my youth. In the old days, Columbia and Warners used to share what is now the Warner Brothers lot, and I had an office that was right next to the backlot in a trailer, and one night when I was working late, I noticed they were making this enormous movie on the backlot, a science fiction movie. And it was so big that they didn’t even know who was working on it. You could just kind of show up, so, for a few nights, I would go work for the art department. Harrison Ford was in the movie, and I soon found out it was called Blade Runner , and I found out it was about robots. And someone pointed at Sean Young, the actress, and said, “Oh, she’s a robot.” And I kind of thought, that’s not what I think Sean Young looks like. [laughs] So later that same night, literally, about three in the morning, on that street, with one of those spinners from Blade Runner , I was sitting there looking at that car because, as a young man, of course, I liked that car a lot. And I suddenly had this real image of a robot, like RoboCop, even blue, probably because that car was blue, who was standing next to that car, looking at all the weird people on that street and wondering why people did the things they did. And the title and the character name sprung to mind in a way that, I must say, has never happened to me before or since.

TITLE

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

NEUMEIER: There were people who wanted to change the title very badly. There was the marketing department at Orion, who, when the movie was done, said, “We cannot market a movie called RoboCop .” Luckily, no one ever really could think of another title. I mean, I certainly didn’t want to. The RoboCop: The Future of Law Enforcement was the title on the script page, and that actually became part of the marketing line.

THEMATICS

PETER WELLER: The most human character in the story is the one who physically, emotionally, psychologically, has been pillaged in the name of progress. Pillaged in the name of progress! So you can see why the Third World countries that were buying this thing, buying the DVD, or selling it, in 2003, were fascinated about the theme of being pillaged by technology. The Trickle Down Theory — if it’s the best for the rich, it’s trickle down, which is a bullshit trope, by the way, because it doesn’t trickle down, really. At least it doesn’t trickle down fast enough for Joe Average to catch up to the gluttony at the top.

PAUL VERHOEVEN: It’s a criticism to do with the Reaganomics of that time, and that is all things that were already in the script when I came to the project, and were things that, as I was just arrived from Europe, were not something that I was very familiar with. And I don’t think that I was attracted specifically by these, let’s say, ironic statements about urban politics, like privatizing prisons and all that stuff. I accepted that, but it was certainly not something that I was extremely familiar with. At first I rejected the project because, living in Europe, I thought it was silly. It took some time to realize that it was not. When I started to see what the movie could be, for me it was much more important that there was this “soul” thing, which has a lot to do with a person losing his identity and finding it again.

WELLER: The thing that Verhoeven said was that I brought some humanity to it beyond what he had expected, and I just have to say that the scenes were brilliantly written — Neumeier and Mike Miner had already written those scenes — but with Paul sort of guiding the way, it was an easy thing to do. By the time we were shooting the heavy scenes with the family, going back to the family, taking off the helmet, I was really in lockstep with the writers’ and Paul’s vision. Because Paul and I had had this conversation in my hotel room about resurrection, that RoboCop wakes up and finds his physical manifestation because of a spiritually given alarm clock. It’s not the usual cliché of vengeance. It’s really about the soul awakening.

SLEEPER

MIGUEL FERRER: I’ve guessed wrong so many times that I try to stop guessing, and I saw that there was a great opportunity for it to be intelligent, and humorous, and exciting, and full of action, and all that, but there was also, I felt, a real danger of it being very bad. [laughs] But I was a big fan of Paul Verhoeven. I was really struggling at the time and would have taken pretty much anything, but this is something I really wanted to do. But, to tell you the truth, when we started it, I figured that it could have gone either way.

WELLER: No. There was no buzz at all. There was no buzz. As a matter of fact, it was considered sort of a half-assed script about a robot. At my age, I wasn’t really thrilled with it when I first heard of it. But Verhoeven is what attracted me to it. I said, if Paul Verhoeven is going to direct it, I’ve seen all his films, and I was a big fan; I thought he was profound, and I knew he took these personal stories of redemption, or a personal story of revitalization, or somebody finding himself with a big opera in the background — Soldier of Orange , it was World War II; in Spetters , it was motorcycle riding. He took a personal story and set it against something sociological. So here you have a personal story of resurrection set against the watershed of America transforming a city of poverty by its privatization, but underneath it, you scratch the surface and you see that privatization is creating the corruption in the first place. They are actually creating the corruption in order to have an excuse to take over the city to make money. When I read it, I thought, “This is going to be great.” I didn’t know we were going to be successful, but I said, “This is good.”

THE DIRECTION

FERRER: I think a lot of times someone sort of approaching the subject from an outsider’s point of view can be the best thing, as a real observer coming to it without a lot of the preconceived cultural notions. Ang Lee in Brokeback Mountain comes to mind, but just getting a fresh look at it I think really helped.

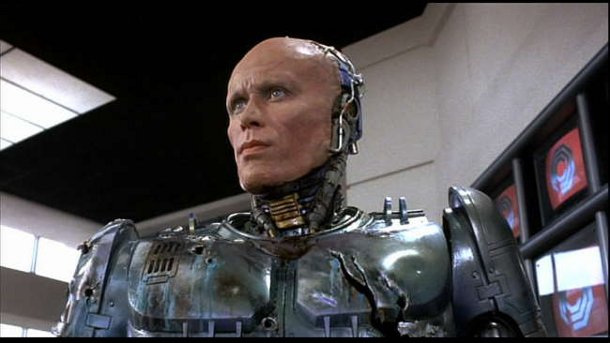

WELLER: He’d done the gothic feudal story [ Flesh + Blood ] with Rutger (Hauer) before this. Verhoeven starts off in sixth gear. I direct now. I direct television, I’m directing a small film coming up, and I’ve been directing for a while. I went to school on Verhoeven. I went to school on a lot of guys: Mike Nichols, and Sidney Lumet, and Woody Allen, to mention a few. But Verhoeven has a taskmaster way on a set, I mean, he drives a set. Sometimes the momentum may step on a few toes, but you’ve got to go. A movie set is not a democracy. A movie set is a totalitarian environment, and the guy that hits the floor called the “director” has to make those decisions, and I learned much from him. I was training for the New York Marathon at the time. I was on a macrobiotic diet. Essentially, I was hanging out with all the bad guys, because all the bad guys were the health freaks. And that’s who my buddies were, were Calvin (Jung), and Kurtwood (Smith), and Ray Wise, and Paul McCrane. It was so intense, that experience, of putting on that suit — particularly doing the face, which took six-and-a-half hours. Stephan Dupuis and the Robo team, Rob Bottin designed this genius applicator… it took six-and-a-half hours to do that prosthetic, and then another hour-and-a-half to get into the suit. And we’d done an eight-and-a-half hour day by the time the crew came to shoot, and you just had to shoot that face out in five hours before the rubber collapsed. There were 27 days of absolute… I wouldn’t say “misery,” but it really demanded a Zen sort of discipline.

I, ROBOCOP

WELLER: I’m sort of a method actor. I’d studied with Uta Hagen, was inducted into the Actors Studio back in the Seventies vis-à-vis Elia Kazan, one of my heroes, and Lee Strasberg, another one. And I was trying to find the internal movement of this guy. At the same time, I said, “Well, this thing is really going to take a massive effort”— and I’d taken mime. I was a mediocre one. I had taken a lot of dance, but I said, “This is going to take athleticism.” And I’d met with a lot of mimes who just wanted to do the usual pantomime. But I’d met with Moni Yakim, who also had studied with the greats. He knew the work of Etienne De Croux and Jean-Louis Barrault, and was with Marceau. And he said, “What we want to do here, I think, is have some sort of liquid movement with a staccato on the end of it, so it’s like butter, but then with a big, hard definition at the end of the movement.” And we started working on it, and I said, “This is the guy for me.” And he designed it, and I just worked on it for four hours a day, that stuff. It was tough, man, but fun.

MONI YAKIM: First of all, he knew he didn’t know what the hell to do with it, and I was recommended to him by some people because this is my specialty. He gave me the script, and he came to my studio, and we did a few improvisations, and we got the chemistry between us, and we decided to work together.

FERRER: Well, you know, he (Weller) knew the job was dangerous when he took it. What can I say. Nobody had any real sympathy for him being in the suit.

YAKIM: It was not the hero that they had in mind. They didn’t know what to do, and, basically, they stopped the shooting. And Peter told them, “Call Moni and he might find a solution for us.” Of course, they rejected the idea because they thought that they were very smart, and if they can’t find the solution, how would I find the solution? So they resisted, like, for a day, but they couldn’t go on shooting, and they were desperate. So the producer called me and asked me to come over to the set. Which I couldn’t because I had a commitment here (in New York). And another day went by in which they did not shoot, and they were losing a lot of money every day. Finally Peter got on the phone, because he felt that this was something that would launch him into stardom, and he didn’t want to give up on it. So he called me and tried to get me to delay the job that I had here and to come over to the set. And since I’d become extremely friendly with Peter, I couldn’t resist him.

So I went, they flew me over there. A car came and took me over to the set. Nothing was happening. Everybody was depressed, especially Paul Verhoeven, who was going absolutely crazy. It was his first chance at doing a big American movie. I came to an extremely depressed place. I had met Paul before that, because we discussed the character, but he hardly looked it to me when I arrived there. And I saw Peter, and Peter said, “How do we go about it?” I said, “I can’t do anything unless you put on the costume.” So he went and they worked on him, again, for a few hours, to put on this costume that was not easy to deal with. He appeared with the costume, and I laughed, because he did indeed look like a huge toad. So I asked him to walk a little bit, and then I realized that it needed just a small adjustment. I asked everybody to leave the set and to give me about an hour to work with Peter.

And I worked with Peter and found out that all was in the rhythm, that we had to throw away everything that we’d done, rhythmically, over the four months, and to create the rhythm that would fit that costume. That, instead of having the bulk as a negative thing, to use it as an asset. So we started to move slower, and to walk slower, the motions were slower. And we worked Peter’s body into the weight of the costume, rhythmically. And, after about an hour, I called Peter, Verhoeven, and the guys, and told them to look at what he can do. And everybody got excited, and they started shooting. That’s the real story. And it was in the papers because Peter Weller actually said it that if I hadn’t come to the set that day, there wouldn’t be a RoboCop.

WELLER: Well, I do Zen meditation. I would meditate while they put on that mask, because that was the only way to get through that. To sit in a chair for six-and-a-half hours while somebody’s messing around with your face? Try that sometime. You’d stab somebody with a fork if you don’t find some kind of meditative process. By the third hour you’re gonna kill someone.

Continuing our expanded version of Jorge Khoury's Making Of RoboCop, originally published in SFX 217.

THE PRODUCTION

NEUMEIER: It was very organic and not just Paul and I, but Paul and I and the production. The production was tough, but, nonetheless, it worked very well in terms of pushing, just developing the movie and making it better, and better, and better. Before we would shoot a scene, the night before, we’d sit down and go, “All right, now we know who these actors are, we know what we’ve got, and, you know, that guy never really worked, and I don’t think we should do it, but, oh, this we could do now, because remember? You saw that thing on the set yesterday.” So you could just kind of refine, and refine, and refine. And it was a great experience for me to go through from one into the other. I mean, I was able to consult and give my two cents on props and everything else. I’m sure sometimes I was just a complete pain in the ass, but in the end, it sort of turned out okay.

FERRER: He (Verhoeven) was certainly in control, and it was far from his first film. It was his first American film, not even his first English-speaking film. And he did have guys that he knew around him. He had Jost Vacano and his whole crowd that he’d worked with in the past. But I think he responded to the American crew with, I’d say, a certain level of suspicion. And I don’t want to say paranoia, but whatever discomfort or uncertainty he might have felt, he generally reacted to in a hostile manner. And I don’t know if that was his nerves at play or what it was, but there was generally a screaming fight pretty much every day. A lot of drama. But it was rarely directed at me, so I just kind of observed it with amusement.

VERHOEVEN: Well, yeah, because I had no help, I would say. Of course, I got help, and there obviously was help from Jon Davison and Ed Neumeier. Ed Neumeier was always there during the shoot. Of course, I left everything behind in Holland: my crew, my cast. When I came to the United States, I didn’t know anybody. Everything was a guess; setting up a crew, or finding the actors, was all unknown territory. Yeah, it’s jumping into the unknown, and that is, of course, very heavy, because you can’t rely on anything you know other than your professional filmmaking. On the other hand, think how it worked… it made me extremely adventurous and open-minded, and I could basically forget the way I had been doing things in Europe, in Holland, and could replace them with new ideas that came from the inspiration in the context of me with the United States. So, by jumping forward into the unknown, you were also able to use everything that was here, everything that was amazing to me, or kind of funny to me, to use that all, basically, in a different way than an American would have done, who would have probably not seen these things, or wouldn’t have looked at them the same way. But I looked at them clearly that way, because everything was new to me, and different from Europe. I think it was a dangerous, frightening experiment. At the same time, nearly from an existential point of view, you could say this jump into the unknown was an enormous source of inspiration.

NEUMEIER: I think there was an anthropological notion of someone from another culture looking at America, and I think this is essentially kind of an older story, which is the filmmakers who grow up someplace else looking at the American film business as this high aesthetic form that they aspire to. I mean, Paul would say that he was a darling in America as a European director, but what he would say is, “All I wanted to do was make American-style, plot-driven films,” and he was actually kind of unpopular in Holland as kind of a commercial [director], overly interested in the commercial form. But Paul had been in the movie business long enough to know that very often you would write a script and then be surprised by what you saw on the screen, as a writer. Now, I actually was a producer on the picture, too, so I was there for the whole time, but I do remember one day thinking, before the movie even came out, “This is the script. This is everything I ever wrote. This is everything I could have hoped for in terms of execution.” By working together so closely on production, we actually added things and made things better. It was a very, very close collaboration.

AMERICAN JESUS

WELLER: The terrific thing that Paul infused in this, even though it was written by Neumeier and Miner, is that Paul infused the images of the theme of resurrection. And when you say “resurrection,” you immediately think of Jesus. Jesus is the pinnacle of that topos, that type, that theme, that we can think of in the Western world. But the theme of resurrection goes back to Egypt, goes back to the Osiris-Horus mythic story of an Egyptian god who was resurrected, dies, and comes back. It’s also present in the Book of Job in the Tenak or Jewish Bible. Job has everything taken from him. There’s no way he can go farther down. But the soul is God-given. This is what Paul gave the film. Paul’s seminal image is that, when Robo starts to have dreams, starts to wake up, that is Murphy’s soul waking up. There are the themes of technology, and progress, and greed, and all the corruption that takes everything away from the common man, but nothing can take away his soul, because it is God-given. The soul wakes up and the body’s resurrected. That’s an age-old topos or theme, and Paul really played it.

NEUMEIER: Well, certainly Leone and the Eastwood Dirty Harry characters and all those kind of things were there. I knew it was definitely a revenge fantasy. But we talked a lot about Jesus and Frankenstein. I mean, Michael Miner and I did, and then Paul. But we never talked about it like, “Oh, this is so profound.” It was more like, “Yeah, it’s kind of like Jesus.” So, for instance, when we’re in Pittsburgh at the Monessen steel factory — we were trying to figure out where we should set the ending. It’s very hard to do big action set pieces if you don’t know what your physical environment is like, and I remember Paul sitting at the edge of this big quarry tank where the end of the movie is set, and he just said, “You know, that’s just one of the most beautiful things I’ve seen.” It had these kind of tall, giant walls, and this kind of water in this tank.

And I said, “Well, if you feel that it’s beautiful, then that’s where we should set the end of the movie.” And then Paul, he didn’t ever say, “Well, I’m going to have him walking on water,” but you kind of knew he was doing that. He knew that he was kind of playing with those ideas. It’s nice to play. It’s nice not to be on the nose as much as to just sort of hint at it. So if you start looking at it, it’s really there. I mean, in the scene where Murphy is being shot to pieces, there’s a moment where his arms are stretched out like he’s on the cross, but it’s only a moment. And Paul knew he was doing that, but he didn’t want it to be so insistent. You know, “Look what I’m doing; I’m talking about Jesus here.” So those were the kind of creative decisions that I think really helped.

VERHOEVEN: Going back to this Christian theme, I always felt that it was true that RoboCop was kind of a resurrected person, a demi-god. You could see him as a Jesus, but I always called him an American Jesus. In the scene at the end where at first he arrests the bad guy, Clarence Boddicker, but then he gets on the streets again and they meet again in the steel factory in Pittsburgh… RoboCop, who is at that point walking over the water, basically, like Jesus, of course, is aiming the gun at Clarence, and states his line: “I’m not arresting you anymore.” He’s saying, “I will kill you.” And, basically, that’s why I’m calling him the American Jesus. Ironically, perhaps, but that is an element, let’s say, of the way Christianity is often interpreted in the United States.

AFTERLIFE

FERRER: It was very topical. I think, for a robot movie with a sort of heavy body count, it had a great deal of very sophisticated humor and satire, more than I think was expected of that kind of picture, and I think that’s one of the things, along with Verhoeven’s sensibilities and his take on the whole subject, which is really what set it apart. I remember Paul saying to me the day that I first saw the finished cut, the final product, the movie that was going to appear in theaters, I was so pleasantly surprised, and I said, “God, it was wonderful.” And he looked at me and he said, “Yes. I think it turned out better than any of us thought it would.”

WELLER: Y’know, by the time that we were almost finished in Dallas, I knew that we were onto something remarkable. Once again, you never know if it’s going to make any money, or whether it’s going to be a success, but I knew I was part of something really wonderful — and so much so that I was on such a fast track with that film, with my diet and my discipline, and all the Robo-movement. The discipline of doing that was such that, when we finished it, I went off to Spain to make a movie, and more or less was bummed out; a depression coming off that high. It was a comedown, like, climbing Everest. [laughs]

FERRER: I’ve got to tell you two things. I really, really believe the summer of ’86 was the best summer of my life. It really was the best time I’ve ever had, and after the picture came out, it absolutely changed everything for me. Everything. And I’m extremely grateful for that. It’s kind of a rare thing that I want to talk about stuff that I’ve done a long time ago, but I have such fondness for RoboCop that I really wanted to talk to you about it. It was a real pivotal point in my life, and certainly set up my career, and changed things in a great way.

WELLER: Look, I did an interview for the triple-DVD for Warner Brothers about eight years ago. I sat in a Warner Brothers office in London for a week thinking I was going to get these dreary questions about how much the suit weighed. Well, this was the worldwide release of this DVD, and subsequently all I got for five days, on phoners and live interviews with essentially the Third World countries of the planet, is what this film represents, thematically, in terms of technology in the hands of the wealthy West, in the hands of what they called, in Renaissance Italy, the Grande, the people with money; thus, technology in the hands of the Western world, and what it was doing as far as dominating and subsuming the Third World. Problems concerning, essentially, progress looting the goods and services of the Third World and basically leaving them a pittance. That’s all they asked me, and I never thought about the movie in terms of that until those interviews. So, to look back on it, I can see that Paul had that in there all the time, that the Western world, symbolized by America but not only America — the entire West — as a Pac-Man of greed using cutting edge technology to subsume, take over, and dominate the world, vis-à-vis that technology. If you take that alone, and you take the theme of resurrection, that is why, I say, I argue, the film has no shelf-life. It is anthropological. You can look at the film in 200 years and see what America was about in the end of the 20th Century.

VERHOEVEN: I remember that when we screened the film here in Los Angeles, I was not there, because at that same moment I was at the preview screening in New York. And that was an extremely diverse ethnic audience there, and they reacted in the most amazing, positive way. And I’ve said this before, but the most beautiful reaction from an audience that I have ever witnessed with my movies is at the end of the movie, where the old man says, “What’s your name, son?” That’s the last line of the movie, “What’s your name, son?” He talks to RoboCop, who just took out and shot (Dick) Jones, and the old man says, “What’s your name, son?” And before he could say, “Murphy,” the whole audience was yelling: “Murphy!!” It gave me goosebumps. That was such an amazing, beautiful moment in my life as a film director; I will never forget that. It was RoboCop that gave that wonderful moment to me, a reaction where people are so involved in the movie that they know exactly what the actor is going to say — even though it was not something that you would expect — but they were so deep into the movie, they had so participated, that they knew at that point what the scriptwriter would write, which was, “Murphy.”So, yeah.Wonderful.

Nick Setchfield is the Editor-at-Large for SFX Magazine, writing features, reviews, interviews, and more for the monthly issues. However, he is also a freelance journalist and author with Titan Books. His original novels are called The War in the Dark, and The Spider Dance. He's also written a book on James Bond called Mission Statements.