The evolution of heaven and hell in gaming

Afterlife and death, as seen through pixels

Earthworm Jim is a series well beloved for its mix of vibrant, smoothly animated visuals and out-of-left-field sense of humor, though the often unrelentingly difficult gameplay made the EWJ titles “those games all the magazines said were awesome but you secretly hated because they were too damned frustrating.” But even kids most prone to fits on controller-throwing rage could fairly easily make it to Heck, an early level in the first game.

Heck is a planet in a faraway galaxy ruled by a demonic, sadistic feline named Evil the Cat. You’ve got all the traditional trappings of a Hellish getaway: grotesque architecture, roaring fire, all colored in hues of red and black. You’ve even got a musical track that starts off with a bit from “Night on Bald Mountain” (aka “the part of Fantasia that gave you nightmares when you were seven years old”).

But things are a little weird here, too – the floating ghost hounds seem like a Hell-appropriate enemy, but it’s not long after that lawyers begin their pursuit of Jim. And then you encounter the fire-spitting snowman mini-boss. The final fight has you dodging searing flames while knocking out all of Evil’s nine lives, one at a time. Sadly, Planet Heck didn’t return in the sequel, though Evil the Cat makes a reappearance trying to pop Jim’s inflated head in the Circus of the Scars.

How can you tell when a game really, really sucks? When nobody cares enough to upload more than a couple of YouTube videos of it.

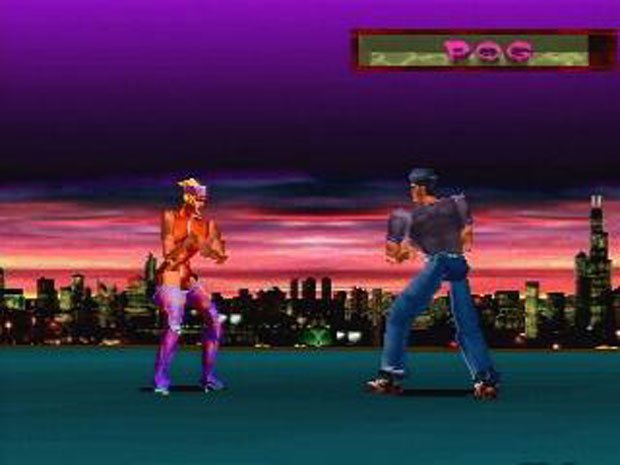

Fight for Life was Atari’s final Jaguar release in 1996. The Atari faithful, loyal to the last, held out hope that this would be the game the system needed to re-assert itself over the upstart Playstation and Saturn. The lead designer and programmer, Francois Bertrand, had come straight from Sega’s Virtua Fighter team, where he’d developed the camera and collision systems. And the game’s concept was totally extreme – you played a dead soul fighting against others in a tournament held by the demonic Gatekeeper. Your prize for winning: Escape from death and return to life!

But what Francois delivered was possibly the most boring fighting game ever created. Fight for Life was glacially paced, lacking in any sort of attack variety and depth, laden with incomprehensible design decisions (thanks for hiding lifebars, those sure aren’t important) and made for a system with a controller not suited for much of anything, particularly fighting games. To top it off, this is probably the most weaksauce version of Hell ever. Oh, wait, it’s not really “Hell”, it’s a purgatory equivalent called the “Specter Zone.” Forget searing lava and demonic hordes, Fight for Life’s backgrounds are… cities, mountains, and deserts. Is the game’s message that winding up in purgatory sucks because it’s boring beyond belief?

Fight for Life came and went with nary a soul caring save for a pitiful few Jaguar fans. But this wouldn’t be the last time the “fight each other to reincarnate” idea would be used, though it would be the last time it actually saw release.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

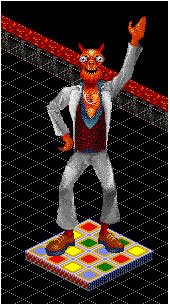

LucasArts was well-known in the 90s for creating interesting and fun concepts for games, be they traditional action titles, point-and-click adventure games, or even a few odd experiments in other genres. Afterlife is one such experiment – a game that puts the “God” in “God sim,” as the goal in the game is not to manage a city or a planet, but Heaven and Hell.

Aided by an angel named Aria and a demon named Jasper, the player is tasked with managing both post-life destinations to effectively house the SOULs (Stuff Of Unending Life) of the dead that flow in. This is accomplished by building containment facilities for the populace (with special building types to house those well versed in certain virtues or sins), training SOULs into worker angels and demons, and making sure gates and transport systems are in place to funnel SOULs to where they need to go. There’s plenty of variety and micromanagement to engage in with the flow of SOULs - not only do you have seven deadly sins (and corresponding virtues) to look after, but you’ll have to plan based on whether or not SOULs believe in things like reincarnation or atoning for sins in Hell before moving on to Heaven.

The player has little control over the planet itself beyond sending the occasional religious figure into the mix to inspire certain types of beliefs. Most of the time you’ll just wind up checking the planet’s level of development (ranging from “Fire” to “Advanced Golf”) and seeing what vices and virtues are currently in vogue and planning around them. Much like other “god sim” titles, disasters happen – wars on the planet can cause mass human extinction, Birds of Paradise can poop all over Heaven’s buildings, and a giant leisure-suit clad demon can wipe out chunks of Hell in a Disco Inferno.

In spite of its inspired premise and clever sense of humor, Afterlife failed to make waves in the PC game market at the time of its release. With LucasArts revisiting its back catalog, however, there’s always a chance that this title might resurface for a new audience to discover.

By 1996, Blizzard had already established itself as a premiere PC developer with Warcraft and its sequel. The company – which is well known for putting out a single release per year, if that – followed up Warcraft II with this dark and sinister action/RPG. Blizzard wouldn’t release a new game until 1998’s Starcraft, but Diablo’s journey to the depths of Hell was more than engaging enough to keep players glued to their monitors for years.

Diablo is an action/RPG that puts you in the role of a user-created hero character. Starting off in a nearby town, you proceed into a randomly generated, multi-floor dungeon and slay demonic hordes with adept mousework. You’re not just treading into the dungeon for fun, of course – the once-idyllic little hamlet you start off in (and save from a demon attack) is actually a focal point in a war between Heaven and Hell. In fact, the guy in charge of that dungeon is one of the Lord of Terror and one of the Three Prime Evils of Hell, the titular Diablo. There’s a lengthy story recounting Diablo’s rise to power, as well, which is revealed as the player moves through the game.

You don’t actually encounter Hell until you near the end of the game, but it’s a pretty creepy place. Dark, dingy, and dimly lit, the only real color in Hell comes from boiling pools of blood contained by walls of sharp, bony, horn-like structures. It’s rather unsettling, and it’s hinted in the sequel that these areas are more of a lesser manifestation of Hell and not a scratch on the real thing. Yikes!

These sort of dark, ambient graphics and settings have since become associated with Diablo fans – so much so that fans complained about early screenshots of Diablo III, saying that the game had become “too colorful.” We’re sure that everyone complaining now will all wind up buying it anyway, because really, what are you going to do? Not play Diablo 3? Pffft.