Escape evil furniture in Amanita Design's creepy new horror game Creaks

Creaks is a puzzle horror game based on 'pareidolia' – the phenomenon of seeing faces in random objects – where furniture is the enemy

Radim Jurda’s greatest fear is being misinterpreted. His response to our question is perhaps not so unexpected: this is the artist and designer’s first ever interview, after all, and he’s keen to get his point across clearly. Indeed, Creaks is an oddity that requires explanation, a puzzle-platformer in which things are frequently not as they may appear. It’s a horror game – although it’s more unsettling than scary – in which you must tiptoe through a ramshackle house in search of an exit. Its inhabitants are frequent obstacles to this. They mess with your head, too. Did that hatstand just move, or did we imagine it?

Platforms: PC / Consoles

Release Date: 2019 (TBC)

Genre: Puzzle Adventure

Developer: Amanita Design

Creaks was born from the shadows in the edges of the eyes, the anxiety at not knowing what is real and what’s simply a trick of the light. It first took shape as a concept around five years ago, as Jurda’s diploma project at his university. “It was all about this aspect of what you see, but also how generally there is some part of the story that you don’t know, and how you fill it with your own imagination,” Jurda says. “And how actually that will become reality for you, and can become completely different to the real thing.” A tricky email exchange, in which Jurda’s own assumptions led to the appearance of a problem that didn’t really exist, had inspired this train of thought. “I had misinterpreted some stuff, and behaved completely differently. So this was a theme that was interesting to me at the time. I was doing these visualisations of feelings versus reality, and how something simple can be difficult for somebody and their psychology. Some simple stuff, it can be a maze.”

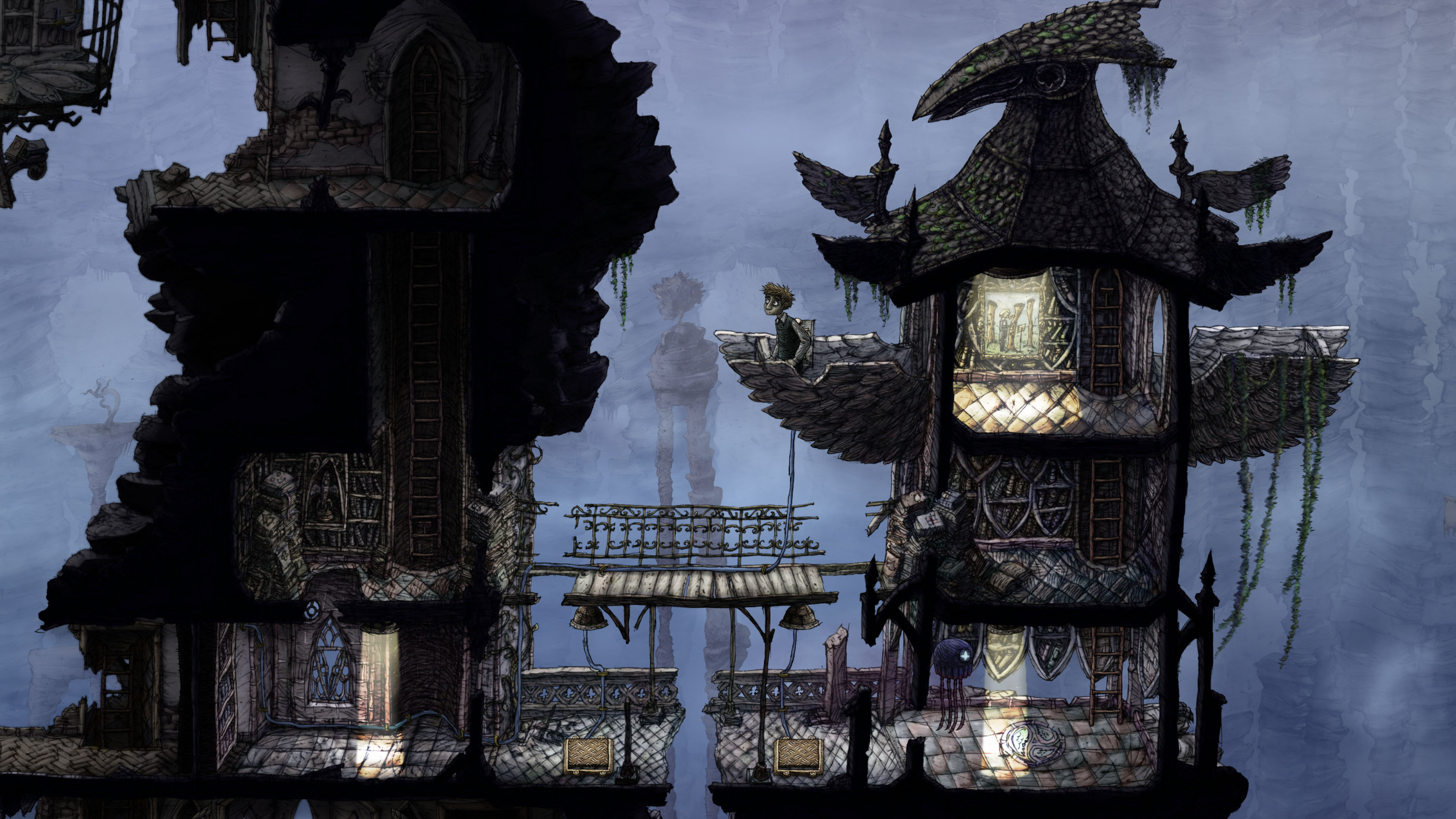

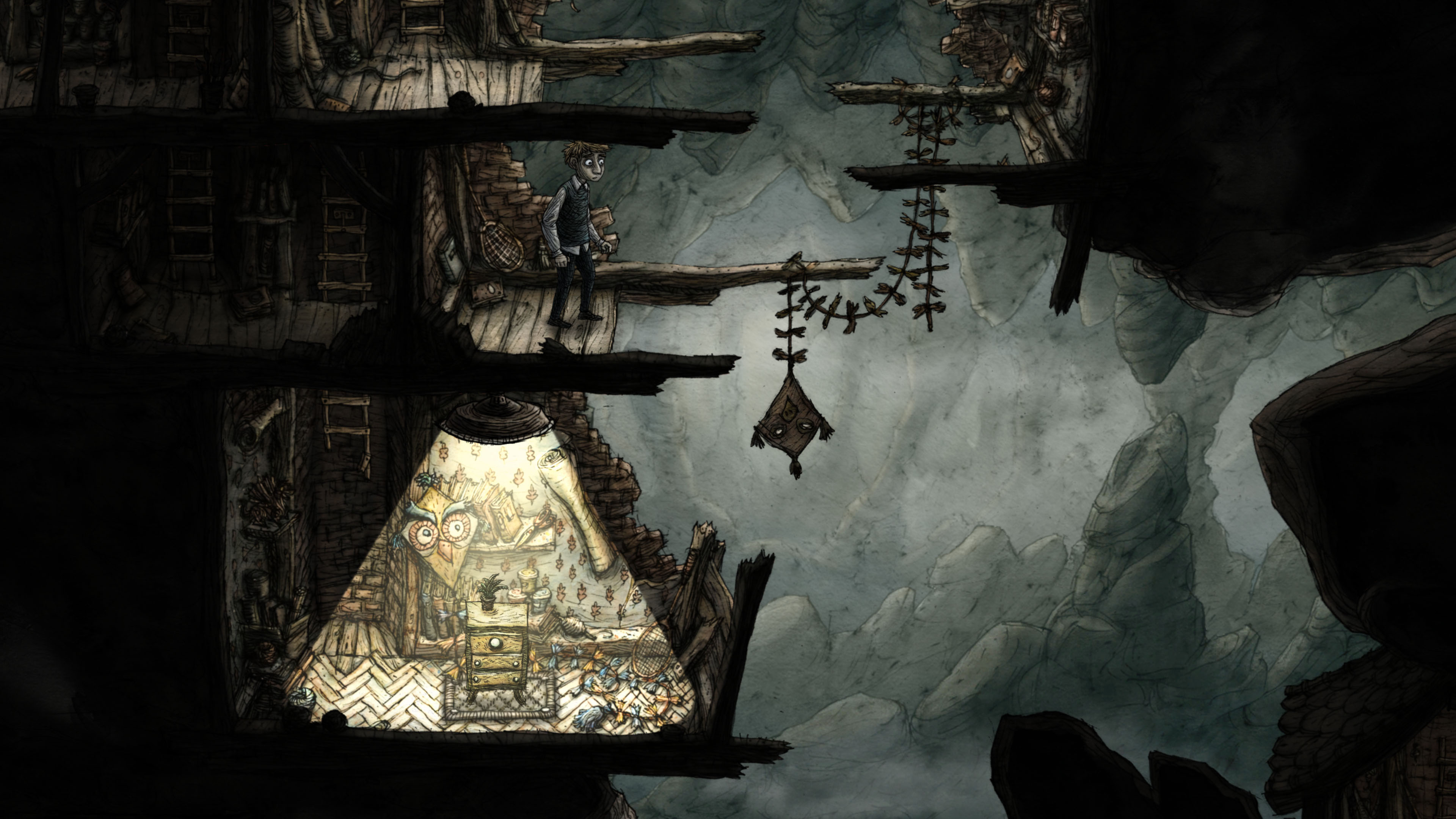

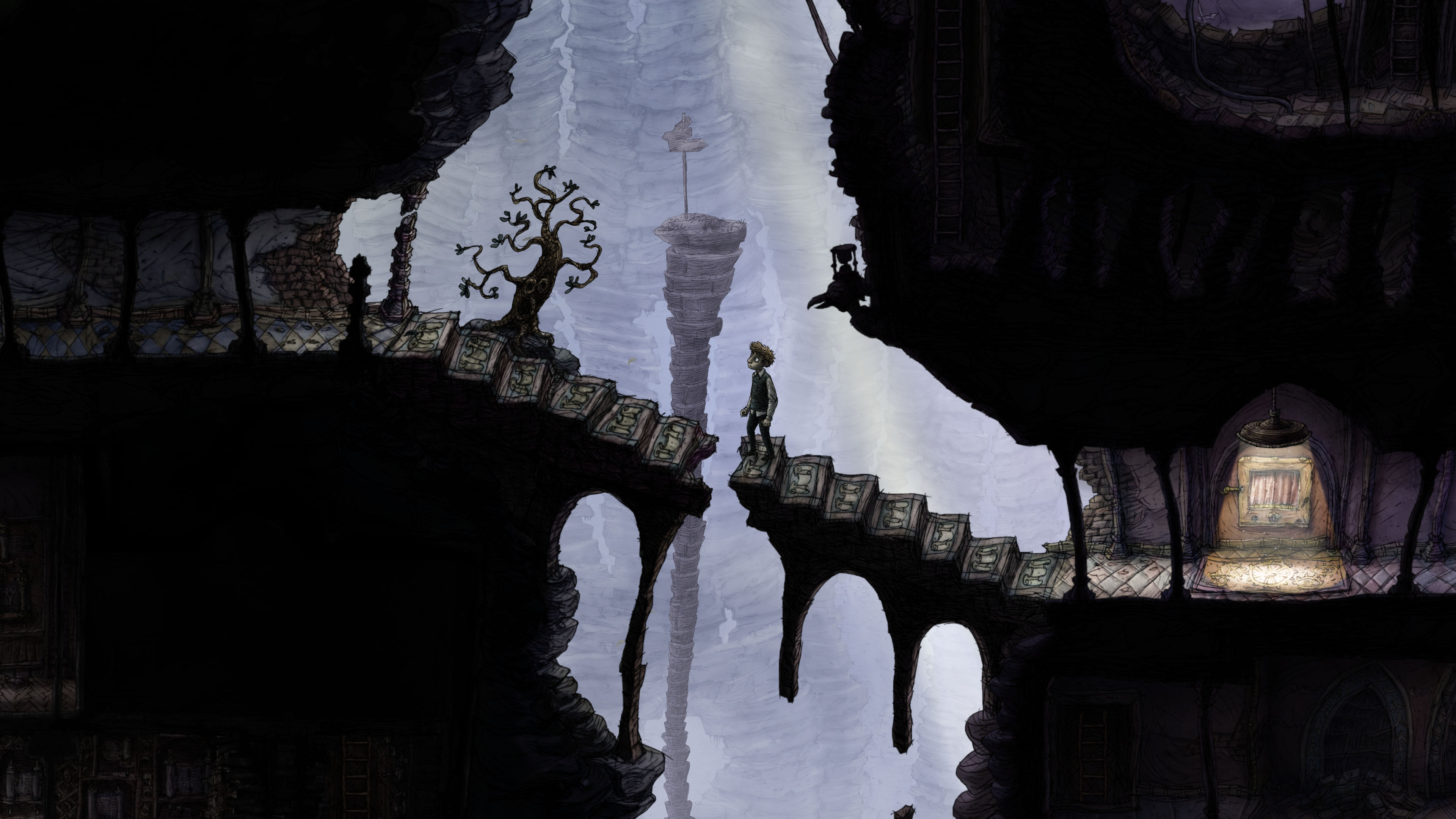

Maze is right. Creaks’ setting is a warren of hand-drawn hallways and rickety ladders: our terrified avatar finds himself lost inside it after peeling back a section of wallpaper in his home and crawling through a hidden tunnel. Whether this world beyond the wallpaper is real or simply an invention of his own mind is unclear. But the atmosphere is as real and as thick as smoke, our hero jogging along nervously. You’d hope a game called Creaks would deliver on the audio front, and it does: floorboards groan and portcullises roar in an almost human manner. And then there are the things hung on the walls and tucked away on shelves. We could swear those shears are champing their bladed jaws at us threateningly, the teapots laughing at us with flapping lids – but every time we look closer, they seem to stop. It’s deliciously awful, a susurration of sound that makes our skin prickle.

The deaths have almost a kind of humorous feel

Radim Jurda, artist and designer, Creaks

It’s almost a relief when a solid, more recognisable threat appears. Mechanical, one-eyed guard dogs patrol the halls: if we get too close, they charge angrily, following barks with deadly bites. This is the first Amanita game in which the player can die – although in an artistic twist, it’s portrayed almost like shadow puppetry. “I had it in my original concepts, and the diploma demo and concept videos,” Jurda says, “So Jakub [Dvorský, Amanita Design founder] saw it from the beginning.” It may have been a new, slightly darker and even more traditional move for the Czech studio, but it was no impediment to its signing of the game: indeed, Dvorský and Jurda agreed that a death state would introduce a degree of tension in a horror puzzle game. “We were just discussing how we would actually picture it,” Jurda says. “We agreed that there wouldn’t be blood everywhere. We had a hand-drawn version, but in the end we didn’t use it. It had to be not too much, not too brutal. It wouldn’t fit the game: it’s like a fairytale adventure. So the deaths have almost a kind of humorous feel.”

Afraid of the dark

The clumsy dogs are starting to grow on us, too, especially as we become more familiar with Creaks’ workings. Screen by screen, we learn to navigate strangely constructed rooms, their floors linked by ladders: switching on lights keeps the dogs at bay, and so progression is about working out how to lure, trap and circumvent enemies using wit and good timing. In fact, in the early stages, it becomes a little rote. And then we hit a switch, and a flood of light catches a dog mid-charge. It transforms into a small chest of drawers, the sudden change in momentum causing it to rattle ever so slightly before settling. Harmless. Caught entirely unawares, we laugh – and flick the switch a few more times, just to check we’ve really seen what we’ve just seen.

Creaks, in fact, was almost called Pareidolia, after the phenomenon that causes human brains to see faces in inanimate objects. “It was built on this – it was the main idea,” Jurda says. “During my diploma, I would go walking in the forest. Somehow you see the shapes of the trees, and your imagination starts to work. I liked this concept that you see something, but you don’t see it completely. And then your imagination works and completes it somehow according to you.” We come to see, and perhaps not see, much more. Gently humming jellyfish creatures idly patrol a set route, reorienting themselves when they bump into walls (which we can use to our advantage) and becoming end tables when illuminated. In other sections, a shadowy twin parallels our every movement, a la Super Mario’s double cherry: the trick is to manoeuvre our doppelgänger underneath a lightbulb and transform it into a hatstand.

Hearing things

When several enemy types come together in areas with multiple ladders, drawbridges, ledges – even, later, a portable lightswitch that we carry and can operate from anywhere – puzzles ramp up in complexity. Indeed, this is perhaps Amanita’s most logic-orientated puzzle game, and it’s something to sink the teeth into. And the musical progress indicators are an inspired move, outstripping the studio’s traditional hint systems. There’s always an element of experimentation at the beginning of a puzzle sequence, as we test out what does what. But as we slowly piece together an order to our actions, the score builds, the melody filling out encouragingly to let us know we’re thinking along the right lines. “We have two to three progresses in the puzzle solution, in the music,” Jurda says, delighted that it’s a noticeable detail.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But every detail in Creaks sings, even though they’re often cleverly positioned in the periphery. From the moving objects on the walls to the shifting nature of the score, itself a kind of whispering communication, Creaks makes its intent clear as a puzzle-platformer of real pedigree and considerable craft. Amanita’s hand is visible here, yes, but only as a means of focusing, intensifying and delivering on an idea. This could have easily been an indistinct prospect, being built around such an ephemeral concept: instead, dreamlike design is balanced with clearly defined mechanical rules with an endearing sense of humour – and there’s room for more additions to be layered on throughout its world’s five areas. If Jurda’s greatest fear really is being misinterpreted, he can rest easy in this case: there can be no mistaking Creaks’ singular identity and intentions. Now, if you’ll excuse us, we’ve got a hatstand to burn.

This preview was originally published in Edge magazine. You can save 54% on a print and digital subscription.