They’re the strangest super-hero team, The Avengers. They’re not held together by bonds of family, like The Fantastic Four, or mutual cause, like The X-Men; their mission (when did they ever actually ‘avenge’ anything?) and legal status often seem vague at best; and their just-buddies-hanging-out vibe is undermined by the simple fact that they don’t seem to like each other very much.

Though generally depicted as the Marvel Universe’s establishment fighting team (both on screen in the recent series of films, including Avengers: Age of Ultron, and off-screen in the comics) – the one the US Government calls whenever Atlantis gets uppity or Mole Man snuffles surface-wards – their membership is as mixed a bag as you could imagine, comprising gods and robots, men and mutants, many of them ex-villains. And though they’ve saved the world enough times to justify their existence – hell, just once would do it – they’ve also caused an impressive stink themselves over the years, be it creating homicidal robots (Hank Pym), taking over the world (Vision), or, more recently, splintering the entire superhero community (Tony Stark, though he had plenty of help with that one).

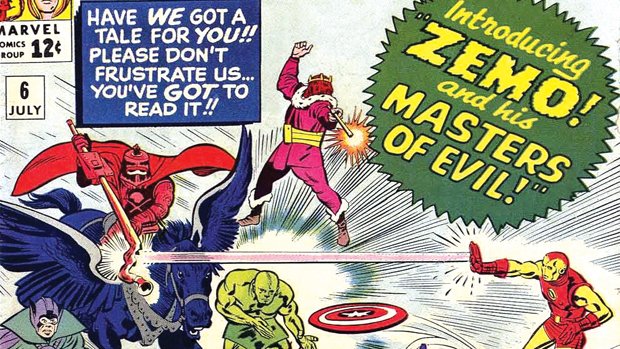

Not that it’s a bad thing they’re so in-fighty and combustible, for The Avengers – an A-list superhero team with almost five decades of history – have drummed up precious few memorable enemies over the years. (Ultron, Kang The Conqueror and – at a push – that bunch of B-listers Masters Of Evil aside, who’ve they really got? Count Nefaria? The Grandmaster? Come on: from Loki to Doctor Doom, Magneto to Thanos, every other Big Bad counts someone else as their true nemesis, The Avengers merely a side issue.)

The Avengers were born in internal conflict – Loki’s machinations pitting four so-so heroes against The Hulk back in 1963 – and their most celebrated storylines of recent times have positively revelled in it. That’s The Avengers for you: not quite amateurs and not quite professionals, highly susceptible to personality shifts and breakdowns, forever bickering, and riddled with potential schisms and traitors. Plus: constantly pulling our fat out of the fire. Here’s how…

Secret Origins

While there was a certain divine, lunatic inspiration behind the creations of The Fantastic Four and Spider-Man, The Avengers came from a much more pragmatic place: Stan Lee liked a huge, soap-opera interconnection between his heroes, Jack Kirby liked drawing extended fight scenes.Those first 1963 issues may have been planned as a neat way to formalise team-ups, but the concept was endearingly ramshackle right from the start. The real superstars – The Fantastic Four and Spider-Man – were conspicuous by their absence, and those who did show up – Iron Man, Hulk, Thor, Giant-Man, Wasp – were largely second-stringers.

The early stories have a freewheeling, anything-can-happen quality almost certainly born of the fact that nobody had quite thought this thing through. Issue #1 begins like a Thor story, with trickster god Loki fooling The Hulk into fighting his half-brother, but soon other heroes show up – The FF make their excuses, apparently deep in ‘another case’ – and before long elephants are being juggled and tyres thrown in a donnybrook that shows Kirby having fun alright, but leaves Stan little room for his precious angst. Finally, with Loki safely locked in ‘an impregnable tank’, the first issue ends with four brief panels where the gang decides to team up permanently, The Wasp seemingly plucking their ‘colourful and dramatic’ name from her tail.

That the others agree to this half-baked plan at all appears remarkable now; not just because it was delivered with all the commitment of ‘we must go for a drink sometime’, but because the Marvel U of the time was hardly a friendly place. Prior to this, guest appearances had been miserable affairs. Heroes would pass each other on rooftops, and when they did interact they’d be arsey about it, self-absorbed and selfish. (It was the rare meeting between heroes that didn’t end with either an offhand dismissal or a misunderstanding-fuelled slugfest that went on for pages.)

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

This is how The Avengers were born, then, and this is how the Marvel Universe remains to this day. Nobody’s perfect, everybody’s got problems, and if you get in my face, I’ll get in yours right back, pal.

The times they are a-changin'

From the beginning Lee and Kirby had made sure we knew their stories took place in the same universe – a place that included all the real cities and social issues, plus many more besides – but now they wanted to redefine the way their characters reacted to each other. The Avengers was their chief tool in this, but while it did alright it was nobody’s favourite, and Kirby was clearly overstretched – he was pencilling Fantastic Four, Thor, X-Men and a million covers too at the time – dropping the book in favour of a revived Captain America. This would have been a disaster for most comics, but with The Avengers it’s where things get interesting.

Jack’s replacement, Don Heck, wasn’t a superhero artist at heart but he now incorporated some of Kirby’s punch to create an effective style, one that grandstanded the human emotion and character conflict. And Lee knew the stories he wanted to tell too, dumping the team’s powerful charter members en masse in favour of man-out-of-time Cap – Kirby’s great World War 2 creation, who’d been resuscitated by The Avengers in #4 – and a selection of rough-diamonds from other books, semi-villains from the Marvel tradition of misguided bad guys.

Hawkeye was a Green Arrow rip-off, a deadly bowman who’d fought Iron Man; more importantly, he was a brash show-off with a chip on his shoulder. Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch were a Euro-duo of oddball siblings, tag-along X-Men baddies who’d become minor fan favourites. And then there was Cap, a worn out old soldier confused by this new world of the ’60s, unsure quite what he was doing but feeling honour-bound to turn his recruits into a team anyway. Constant churn was in The Avengers’ DNA, of course; by the start of #2 Ant-Man had become Giant-Man, and by the end Hulk had quit the team. But this new direction was a sea-change, even if ‘Cap’s Kooky Quartet’ would more memorably struggle with self-doubt and insecurity than they did with villains.

Still, things would slowly get better. Henry Pym – the one-time Ant-Man/Giant-Man, now renamed Goliath and stuck at a freakish 10-foot height to give him something to moan about – was back, as was his gal pal The Wasp. Avengers Mansion headquarters – a block-sized townhouse right on Fifth Avenue – was established, with loyal butler Edwin Jarvis slotting into the Alfred role. But it was with the arrival of two new heroes and a pair of new creators that The Avengers finally took flight – and for a brief period in the late ’60s/early ’70s, it would become the most exciting comic in America and perhaps the defining book of the Marvel Universe.

The Ultimates: Roy Thomas & John Buscema

At some point towards the death of the ’60s, The Avengers suddenly gets good. It had been building, ever since Stan – tired and busy – had passed the reigns to Roy ‘the Boy’ Thomas with #35, but it’s with #41– and the arrival of John Buscema, perhaps the great Avengers artist, that the strip explodes. This is now a proper golden age, Thomas getting noticeably more adroit and inventive with every issue. He brought to The Avengers a fan’s obsession with detail, filling out the backstories of minor characters, making unexpected but logical links between events in past issues, and allowing his heroes to express character through (sometimes endless) chatter.

He cared, in other words, showing an emotional and intellectual connection to the material that nobody, not even Lee, could match. To Thomas, the individual stories sometimes seemed less important than getting the continuity right, or establishing background details; when he was on fire, Marvel books felt less slapdash and, well, ‘fictional’ – and more like a series of authentic reports from another world.

Thomas had a near-fanatical need to bring back old characters – even those best left forgotten – and explain Lee’s many inconsistencies, even if it tied him in knots. But to think of him as a detail-merchant only would be to do him a huge disservice. Thomas could innovate also. He milked the poignancy of Cap’s situation and explained Hawkeye’s rebellious nature through the flame he carried for Black Widow.

Pop culture references would be dropped with new abandon, but so would heavyweight philosophical issues – and literary references too. The throwaway one-page coda to the mighty #57, in which a young black teen plays with Ultron’s abandoned head before wandering off, after – it seems – unknowingly saving the world, would be remarkable enough anyway; that Thomas left it dialogue free, but accompanied the action with extensive quotes from Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias’, allowed it to become one of the most confident, unexpected moments in all comics. The college fanbase went wild.

Vision on!

Thomas’ run took us to about issue #100, and – though it splutters occasionally – it’s a consistent achievement to stand comparison with Lee-Kirby on Fantastic Four: everything Avengers since, no matter how glorious, lives in its shadow. Highlights were many. Roy used Goliath and The Wasp to explore mental breakdown and marital conflict, the centrepiece being a nervous breakdown for Hank Pym that caused him to take on a new bad boy persona, Yellowjacket.

He brought Black Panther from his jungle kingdom to the mean streets of NY, putting the first black superhero of any note front-and-centre in the premier superteam, and through him introduced Marvel’s version of race-hate to the mix. This version of The Panther was a two-fisted Sidney Poitier, and his clash of heads with The Sons Of The Serpent brought us a detailed look at how the media of the Marvel U reacts to its superheroes. It was strong meat, the letters page a-buzz with opinion, and it seemed comics, for the first time, were beginning to engage with the anger at the centre of American culture.

But though The Panther was immense, and Yellowjacket shocking, the new face Avengers fans really fell for was Vision, a coldly aloof android, given human memories and feelings but in constant turmoil over his true nature. As was Roy’s wont, this ‘original’ creation – the first hero created specifically for The Avengers comic – was actually a spin on a minor Joe Simon/Jack Kirby character of Roy’s youth, but the take was all new. Created to be evil, this modern Vision rebels against his creator, Ultron, and has self-doubt tattooed at the core of his being. Where did I come from? What about my memories and feelings? And, is it possible to be ‘basically human’?

When the team finally welcomes him into its ranks, Vision turns away, overcome. John Buscema, at his considerable peak, offers up such a memorable last page to #58 (‘Even an android can cry’) that it’s become one of Marvel’s greatest-ever single panels, heroic and sad, a plastic man struggling with issues of legitimacy and identity, untold agonies bursting under the surface of his care-nothing shell.

By now Buscema’s elegant-yet-brutal style had become the signature look of Marvel’s post-Kirby years, his bold masculine style thick with heavily-muscled Greek god heroes in dramatic, theatrical poses – ‘Michelangelesque’, Lee called it. The Avengers was his first regular gig at the new Marvel, and he was an immediate sensation – fans were thrilled by the sheer craft, as exciting as Kirby but more realistic, more human. No one does an anguished hero quite like Buscema, and every issue of this run boasts a dozen knock-out panels: our first sight of Vision, “heedless of the torrential downpour… because it does not touch him,”; Jan flashing Jackie Kennedy-style eyes (“I’m going to marry him!”) at the end of #59; Kang’s throne-room in #69, fully deserving of its (crazy-rare at the time) double-page spread.

Avengers Forever

The Avengers story doesn’t end here, of course – how could it? But though the team has boasted many great writers and astounding artists in the years since Thomas and Buscema, all have walked in their footsteps. Among the best was Steve Englehart, who mixed snappy, chatty repartee with an angry rejection of establishment values; more than Thomas, even, his 1972-76 run was an infernally complicated, sub-plot littered thing, the membership roster in constant flux.

Jim Shooter, who followed, was graced with better art – not least the growing talent that was George Pérez – and would prove a stabilising influence, his run an object lesson in well-crafted comics. After this came Roger Stern (an especially strong turn) and John Byrne, Bob Harras, Kurt Busiek and Geoff Johns. (There are periods we’ll skip over completely here, mind; and yes, ‘Heroes Reborn’, we’re talking about you!)

More recently there’s been ‘Avengers Disassembled’ with Brian Michael Bendis rebuilding a new team (or teams) in his image, mixing the biggest guns of the Marvel Universe (Wolverine, Spider-Man) with personal favourites like Luke Cage and Spider-Woman. These storylines – well known, much discussed – tend to split fandom down the middle, much as ‘Civil War’ and others have fractured Marvel’s superhero community, but you can’t deny the quality of the art, or the impact they’ve made.

Nor should we complain about their ultimate outcome, for Bendis – love him or loathe him – has done what many have tried (and often failed) to do, put The Avengers central to the Marvel Universe again, where Thomas and Buscema had them, and where they've been going strong ever since.

Click here for more excellent SFX articles. Or maybe you want to take advantage of some great offers on magazine subscriptions? You can find them here.

SFX Magazine is the world's number one sci-fi, fantasy, and horror magazine published by Future PLC. Established in 1995, SFX Magazine prides itself on writing for its fans, welcoming geeks, collectors, and aficionados into its readership for over 25 years. Covering films, TV shows, books, comics, games, merch, and more, SFX Magazine is published every month. If you love it, chances are we do too and you'll find it in SFX.