"These characters are like my children": Street Fighter's community of players, creators, and fans on what makes the series so special

Since 1987, Capcom has delivered bonecrunching blows and spectacular special moves to the delight of gamers worldwide

For over 30 years, Street Fighter has been at the pinnacle of the fighting game genre. Like a crafty veteran prize fighter, Capcom has managed to not only keep up with its competition, but outfox it along the way. Rivalries with the likes of Mortal Kombat and The King Of Fighters couldn’t halt the rise of Street Fighter, and nor could the rise of the three- dimensional fighting game. Even the changing fortunes of the fighting game genre as a whole haven’t been able to floor this series. The first game was a critical success that did good business in the arcades, but it’s seen as little more than a historical curio today.

Get every monthly edition of Retro Gamer, the award winning guide to classic video games, delivered straight to your door for less than £4 an issue

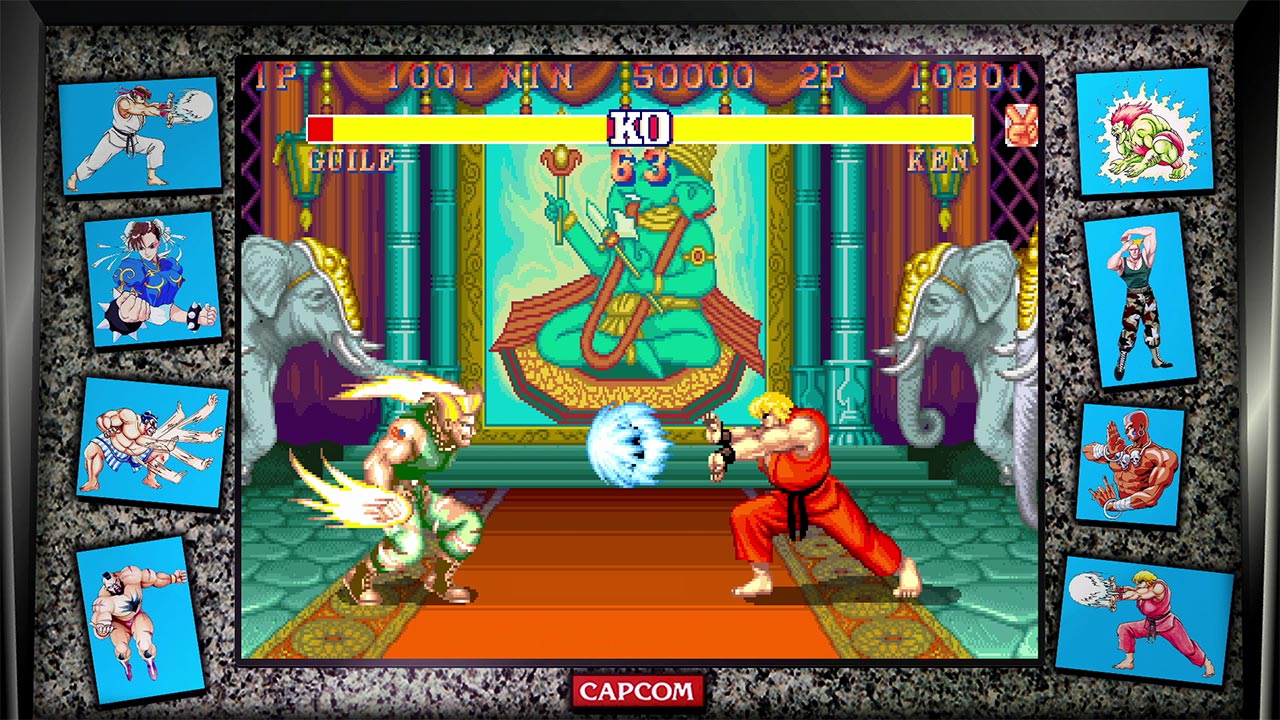

That’s because Street Fighter II redefined the genre in 1991, setting the standard for 2D fighting games for decades to come and kicking off a craze that revitalised the arcade market. Via Street Fighter, Capcom stood atop the 2D fighting pile for the remainder of the Nineties with the popular Street Fighter Alpha series and hardcore-friendly Street Fighter III series. Then in 2008, Street Fighter IV revived the series and ushered in a fighting game renaissance, drawing mainstream attention back to the genre. Street Fighter 5 attracted record- breaking numbers of competitors to the prestigious Evolution Championship Series fighting game tournament in 2016.

Over the years, Street Fighter has busted out of the arcades and into the modern esports scene, and has transcended videogames to become a part of broader pop culture. There aren’t many games that would be instantly recognisable when referenced in a Jackie Chan film or an episode of Family Guy, but Street Fighter shout-outs made it into those and more besides. The series has inspired comics, animated movies, card games and even a major Hollywood film starring Jean Claude Van Damme, Ming-Na Wen and Raul Julia. Of course, what goes into the creation of a good Street Fighter game hasn’t changed much over the years.

Building the bruisers

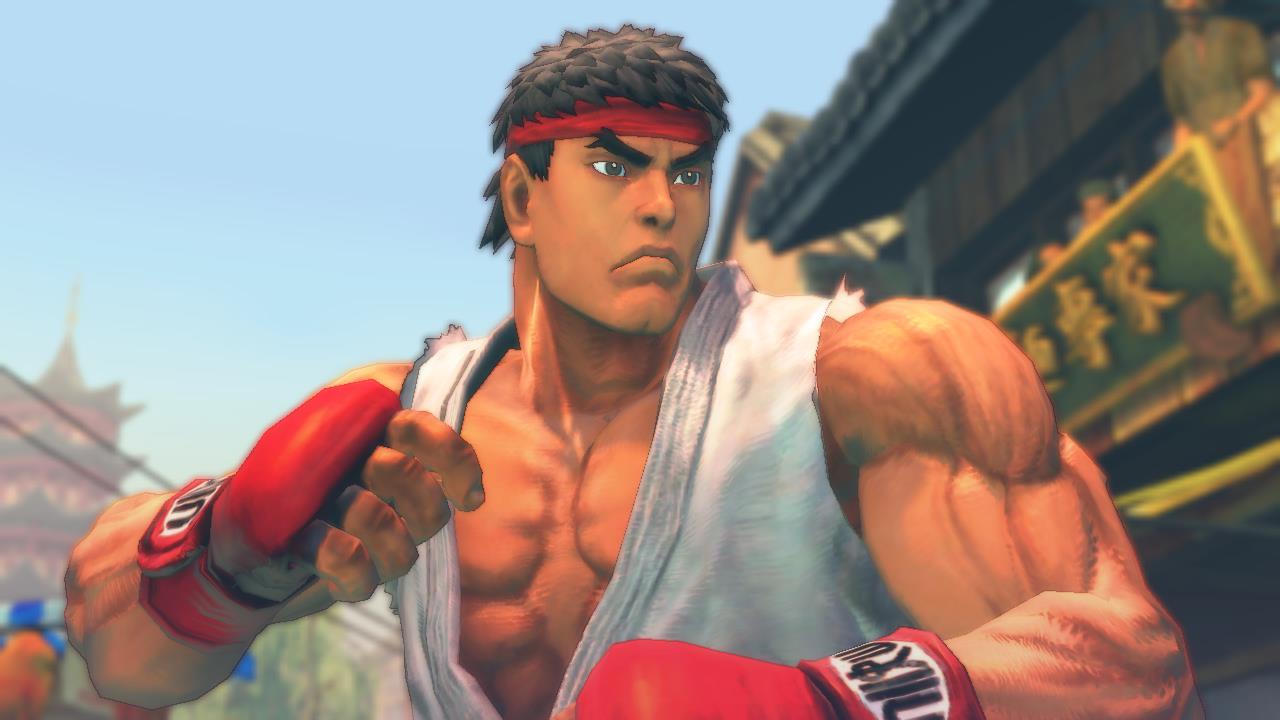

Every Street Fighter player has a preferred strategy – and in the game, those strategies are represented by their characters. As a result, character design is of utmost importance to the series. Whether you want to get in close and deal lots of damage, play keep-away and punish mistakes, or even play a deliberately weak character as a handicap, Capcom provides a character with the attributes and move set to let you play your game. So with decades of hindsight, it’s strange to think that the original Street Fighter game’s characters represented obstacles to overcome. To do that, you had a generic martial artist with a single skillset: Ryu.

This need to combat fighters of all types ultimately ended up informing the character’s abilities. “In terms of gameplay, he’s a great all-rounder and easy to use,” says Yoshinori Ono, a series veteran and the executive producer of Street Fighter V. In Street Fighter II, the number of playable characters was increased to eight. This meant that for the first time, the developers had to design a multitude of characters to play both with and against, and could explore the aforementioned offensive and defensive extremes.

We’ve often wondered what the starting point is, so we call Street Fighter V chief director Takayuki Nakayama into the ring; do the designers come up with character designs to fit certain fighting styles, or design cool-looking people and then decide how they’ll fight? “Both of those approaches have been used but we actually mostly come up with them at the same time,” he explains. “We think about what kinds of moves would be fun at the same time as we’re thinking about what kind of design would best show off their moves.”

Character design has always been a difficult process, with many ideas trialled and dropped along the way – rejected Street Fighter II designs include a bullfighter and an American amateur wrestler. According to Nakayama, it remains difficult to nail down. “We go through at least 100 versions when we are designing a brand- new character, going through many iterations of their appearance, storyline and moves,” he explains. Such a process must surely take a long time?

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

“It obviously depends on the specific character but I’d say, broadly, it takes five people three months to design one character,” he confirms. “And then it’s a further six months to finalise their moves and animations.” Something that has always been a part of Street Fighter is its international flavour – the original game featured fighters from the USA, Japan, China and the UK.

“The fact that the original Street Fighter II had The World Warrior as its subtitle tells you that fighters from around the globe coming together to compete is not just a natural part of Street Fighter but an essential part,” says Ono. “I think that it also lets players feel more connected to the game when they see a character from their part of the world in it, and maybe it’s a hook for them to get into the game in the first place.”

However, new characters are only one part of the story. While Street Fighter’s cast and the bulk of the characters in Street Fighter II and Street Fighter III had to be designed from scratch, the Street Fighter Alpha series provided a mixture of new and returning characters that has become the model for new instalments to the series going forward. How does the team go about bringing these older characters back after long absences?

“The first step is researching how the character was played in the games they previously appeared in. We play those games and watch videos, and even reread the old design documents to work out what the original intent behind the character was,” says Nakayama. “Combined with our estimation of what players want from the character and how they like to play as them, we recreate them and then work on eliminating the aspects that aren’t in line with our vision.”

For Ono, it’s hard to pick a favourite. “Hmm... I get asked this a lot. The characters are like my children – I don’t like to engage in favouritism,” he hesitates. “I love R Mika a lot, and used my position at Capcom to bring her back in Street Fighter V,” he explains with a chuckle. ”But then again, I joined the company in the Street Fighter II era and worked on the sound team, I do have a special place in my heart for Cammy, since she was part of my work back then.”

But what of the Blanka toy that Ono is often seen with? ”Well, he’s been my travel buddy around the world for over ten years now, so he’s beyond the level of like or dislike.” But despite all of the new characters over the years, none has displaced Ryu as the face of the series. “I think it’s his personality that makes him resonate so much,” says Ono. “He doesn’t stand out, he values effort, he’s a man of few words, he’s kind of mysterious, and there’s no one who you could say he’s similar to. I think that’s what has kept him popular over the long history of the series.” It doesn’t take much to convey that either, as occasional post-match win quotes will suffice. “He also has the ‘Perfect Attendance Award’ for the series and that is something that I think shows his dedication,” Ono laughs.

The sweet science

If you’ve ever wondered why some people passionately prefer Street Fighter Alpha 3 to its predecessor, or why players of Street Fighter III: 3rd Strike didn’t necessarily get on well with Street Fighter IV to start with, it’s usually because of the fighting mechanics. As a basic example, consider throw attacks. Introduced in Street Fighter II, they allowed a player to inflict a damaging attack on blocking player – thus reducing the viability of defending your way to a time out victory. But from Street Fighter III onwards it’s possible to ‘tech’ throws, reducing damage or even cancelling the throw entirely with an appropriately timed input – thus limiting the usefulness of such moves.

By tweaking the abilities and options available to players in this way, Capcom can dramatically change the way games feel. “It changes a lot just because it makes the meta different,” explains Justin Wong, a professional fighting game player. “If there was parry, you have to think twice in using long-range normals, if there is focus attack you have to think about how to break the opponent’s focus attack since it can absorb one hit. Each different game mechanic changes the meta and also changes the tier list as well.”

Of course, Street Fighter II’s defining mechanic famously originated as an unintended side effect of another system. The ability to cancel the animation of a normal attack into a special move, creating a combo, was accidentally added when the developers were making special moves easier to pull off but was considered interesting enough to include in the final game. Landing combos has become key to maximising your offensive opportunities over the years, and those simple origins are far behind us.

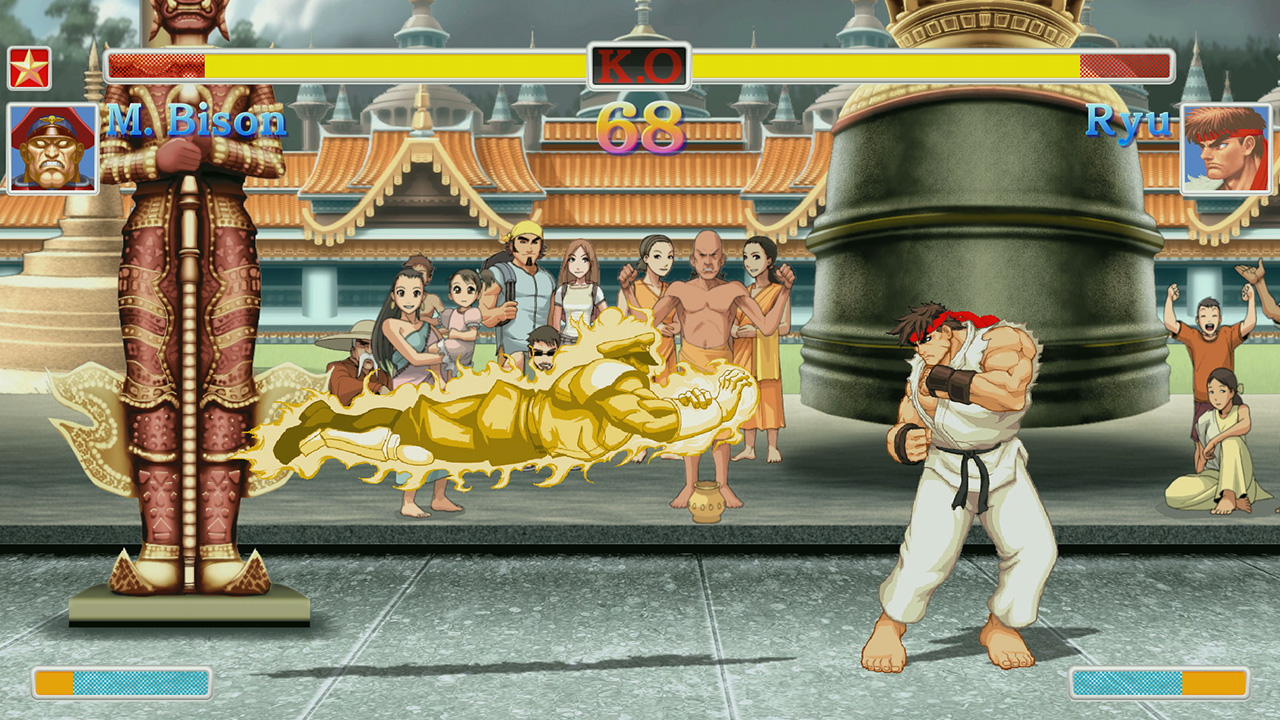

“Street Fighter’s combo system evolved a lot,” says Justin. “Back in the day there was no combo count but now there is, so people can see what is a combo and what is not a combo. It also changed a lot with juggles, using the game mechanics to extend combos to make them longer.” Street Fighter Alpha introduced a mixture of mechanics that enhanced both offensive and defensive options. The one that symbolises this balance most effectively is the air guard – although it’s an extra blocking option, it’s one that makes aggressive moves like jumping towards the opponent much safer.

Likewise, the Alpha Counter allowed players to turn defence into attack, burning one segment of your super meter to hit an opponent in response to a blocked attack. Escape rolls also ensured that your opponent couldn’t always predict where you’d be standing when you got up from being knocked down. Street Fighter Alpha 2 added the devastating Custom Combo, a DIY super move that could inflict huge damage, and Street Fighter Alpha 3 allowed you to use Guard Crush to punish players that blocked too much.

Street Fighter III: The New Generation added a variety of new movement options that significantly increased the scope for aggressive play. For the first time, a double tap of the joystick forwards or backwards allowed the player to dash in the appropriate direction, closing distance quickly. By flicking the stick downwards prior to jumping, you can perform a super jump, covering additional distance. Hitting down when knocked down would also cause a quick stand, throwing off your opponent’s attack timing and allowing you to get straight back into the fray.

And then there’s the parry – a curiously aggressive defensive move. By pushing the stick towards the opponent in time with their strike, you can nullify damage and recover before them to launch your own attack. 2nd Impact introduced EX moves, powerful variants of certain regular special moves that cost super meter to use. If all that aggression rubbed you up the wrong way, the Street Fighter IV series was probably more to your taste. The Focus Attack was a powerful new ability that allowed players to absorb an attack and deliver a devastating strike in response – one which would induce the new ‘crumple’ state, in which the enemy is falling but still vulnerable to attack.

The Ultra Combo was also introduced – a secondary super gauge which charged only upon receiving damage, allowing for some extraordinary comebacks. The pendulum has swung back, with Street Fighter V adding V Triggers and V Skills, character-specific abilities that skew towards aggressive play, as well as Crush Counters that allow players to carry on combos after countering a weaker attack with a strong attack. However, defensive characters aren’t as disadvantaged in competition as players initially believed, and that’s the beauty of Street Fighter’s mechanical depth – it can take years to fully work out what’s going on and how best to work within a given game’s rules.

Something special

There are many things that go into making your favourite Street Fighter character play in their own unique fashion, but arguably the most important is special moves. Don’t take that from us, though – take it from multiple time Evolution championship winner Justin Wong.

“Special moves are always important throughout the years because they are what makes the character who he/she is,” says Justin. “Ryu would not be Ryu without the Hadoken and seeing the evolution of it being better/worse has always been a treat.” As compared to normal attacks, special moves are a little more difficult to perform in that they require a combination of joystick movements and button presses.

The trade-off is that these attacks typically have properties that aren’t found in other moves. Some might hit multiple times or send you to the other side of the screen in the blink of an eye. Others launch projectiles, others still nullify and repel those projectiles. In any case, they have a huge impact on the way you play.

When creating special moves for characters, three key considerations are taken into account: “Individuality, coolness, and accessibility,” according to Street Fighter V’s chief director Takayuki Nakayama. But one thing that Capcom tries to steer away from is introducing more powerful moves in exchange for more difficult inputs. “We try not to have any moves that are really hard to pull off. The strength and difficulty of a move should not be in its input command but in the strategy of deciding when to use it – the timing and the frames, and how to work out the risks and rewards,” Nakayama explains.

Does the team ever come up with moves that end up suiting another character better? “Not often, but it has happened,” confirms Nakayama. “We also sometimes reuse ideas that were cut from games that didn’t come out.”

Between games, a set of special moves is what keeps a character familiar. If you know how to pull off a character’s moves in an older game, the chances are high that you’d be able to jump straight back into playing with them in Street Fighter IV or Street Fighter V. Of course, there are exceptions – Chun-Li, for example, has had her Kikoken fireball changed from a charge motion (holding back, then forward) to a half-circular motion and back again.

"It takes five people three months to design one character"

Takayuki Nakayama

“I feel that the reception has been positive,” says Nakayama when asked about such changes. “We only make changes in order to bring the inputs in line with the character’s fighting style, or when two moves have similar inputs which can cause players to do the wrong move at critical moments.” One function that special moves perform particularly well is differentiating characters that are otherwise quite similar, such as the trio of Ryu, Ken and Akuma.

“Each character has to have their own concept defined. Ryu has weight in each attack, and is very defensive. Ken is better at combo attacks and has a certain fl ashiness, so when he starts attacking he keeps going. And Akuma has the best parts of both but takes more technical mastery to use well,” Nakayama explains. “Based on these concepts, we separate out the abilities of their moves. Ken is a character where you want to rush your opponent, so he has lots of hits, and his fi sts brush up against the ground so friction causes them to go on fire – that kind of thinking is how we distinguish each character.”

The natural culmination of the special move has been the rise of the Super and Ultra attacks. When introduced in Super Street Fighter II Turbo, Super moves were just more powerful variants of special moves. But in recent years, the gameplay function has remained the same while the graphical presentation has turned them into miniature cinematic attack sequences, with dynamic camera angles and detailed facial expressions making them into much more of a spectacle.

“This trend started in Street Fighter III and was firmly established in Street Fighter IV,” says Nakayama. “I think they simply came from wanting to show powered-up versions of special moves in really creative and cinematic ways.” Land a couple of Supers and you’ll agree that they combine flash and function into something incredibly satisfying.

This article originally appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. For more great gaming coverage, you can subscribe to Retro Gamer here.

Nick picked up gaming after being introduced to Donkey Kong and Centipede on his dad's Atari 2600, and never looked back. He joined the Retro Gamer team in 2013 and is currently the magazine's Features Editor, writing long reads about the creation of classic games and the technology that powered them. He's a tinkerer who enjoys repairing and upgrading old hardware, including his prized Neo Geo MVS, and has a taste for oddities including FMV games and bizarre PS2 budget games. A walking database of Sonic the Hedgehog trivia. He has also written for Edge, games™, Linux User & Developer, Metal Hammer and a variety of other publications.