How Scandinavian thriller Last Days Of Snow is channelling cinema to bring unprecedented immersion to video games

This Norwegian narrative adventure could be your new favourite breakout hit

The opening sequence of this narrative adventure from Norwegian micro-studio Loeding is one of the most distinctive intros we've encountered in a long time. It all happens in a child's mind: 12-year-old Oskar dreams of a world presented in a 2D ASCII aesthetic, with code built from letters and symbols. These form a top-down maze, within which we collect strings of code, allowing Oskar to establish something referred to as 'true connection'. What follows involves a startling transition that's almost like an accelerated history of video games, taking us from the medium's most rudimentary building blocks to its cutting edge in a matter of moments.

As we complete a simple puzzle, nudging a block onto a pressure plate to keep a door open, the maze starts to change, its walls and floors shifting to form a glowing outline of a child. Within his first tentative steps, the environment seamlessly morphs into a sun-dappled forest of near-photorealistic quality. Instructed by a mysterious voice to head down a nearby well, Oskar dutifully climbs up and takes a leap of faith. The camera follows closely behind, plummeting down before twisting to face upwards, as the well's opening shrinks into nothingness. Then, from the pitch blackness, it rises again, this time emerging from the pupil of Oskar's eye as he wakes up.

The camera's journey isn't over yet either, as it moves through his bedroom window and across a few feet to capture his mother, groggily accepting a phone call from Oskar's inventor uncle, Leif. That director Jonathan Nielssen is a graduate of the UK's National Film And TV School is therefore no surprise – though the idea for Last Days Of Snow only came after he left.

The white stuff

Having been travelling abroad since he was 18 (he's now 27), Nielssen returned to his home town only to be struck by how much it had changed in the intervening years. He took hundreds of photos and videos at night to capture its peaceful ambience, and used it as inspiration for what would become the fictional Norwegian town of Barvik. The game is set in 2050, but Barvik is in stasis, a community that has become, as Nielssen puts it, "a time capsule" of the 1990s. With its residents rejecting any and all technological advances since then, it's a place that finds itself 60 years behind the times.

Last Days Of Snow, however, is anything but old-fashioned – particularly in the way it's being made. Having spent a couple of months tinkering with snow-deformation tech, Nielssen contacted Nikolay Savov, a producer with whom he'd worked on student game Falling Skies, which made waves at a few events in late 2017 before being scrapped (the pair are coy about the precise reasons). Savov contacted FBFX, a London-based company that provides special effects costumes to the film and TV industries, and using FBFX's 130-camera capture setup, scanned four actors to pore-level detail, before recording half an hour of footage with performance-capture studio Centroid3D at Pinewood Studios.

It's an expensive process, especially for an independent studio, but Nielssen had given himself a head start, having bought a DSLR camera to photograph his home town. "With the snow outside, you get quite good lighting to do photogrammetry," he laughs. "I did tests with that and then that's how I created a workable pipeline. I basically took a scan using my own face and found an easy, cheap and efficient way to get that into the engine. This helped us start a dialogue with FBFX – they knew after we had scanned the actors we could just take it mostly straight into the game."

Although we only get to see a snippet, the fine performance of Christy Meyer as Oskar's mother Elsa in particular suggests it was worth the outlay. But surely a full game would be prohibitively costly for such a small team? Nielssen doesn't believe that photorealism is necessary to help us empathise with human characters – he rightly notes that Pixar can tug effortlessly at our heartstrings – but he does think it's important for games to try to push the technical envelope where possible, even for smaller teams.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"It brings it closer to the quality of... let's say a film, which in turn might make a broader spectrum of people interested both on the consumer side and also in terms of artists taking games seriously." Financiers, too, it seems; after doing the rounds at trade events recently, Snow attracted an investment grant from the Norwegian Film Institute, enough for Savov to start thinking about renting a small office space rather than working from his parents' living room, or the kitchen of environment artist Gustav Morstad, the third of the studio's full-timers.

"Making a good story is a long, long process. It feels a bit like archaeology."

Jonathan Nielssen

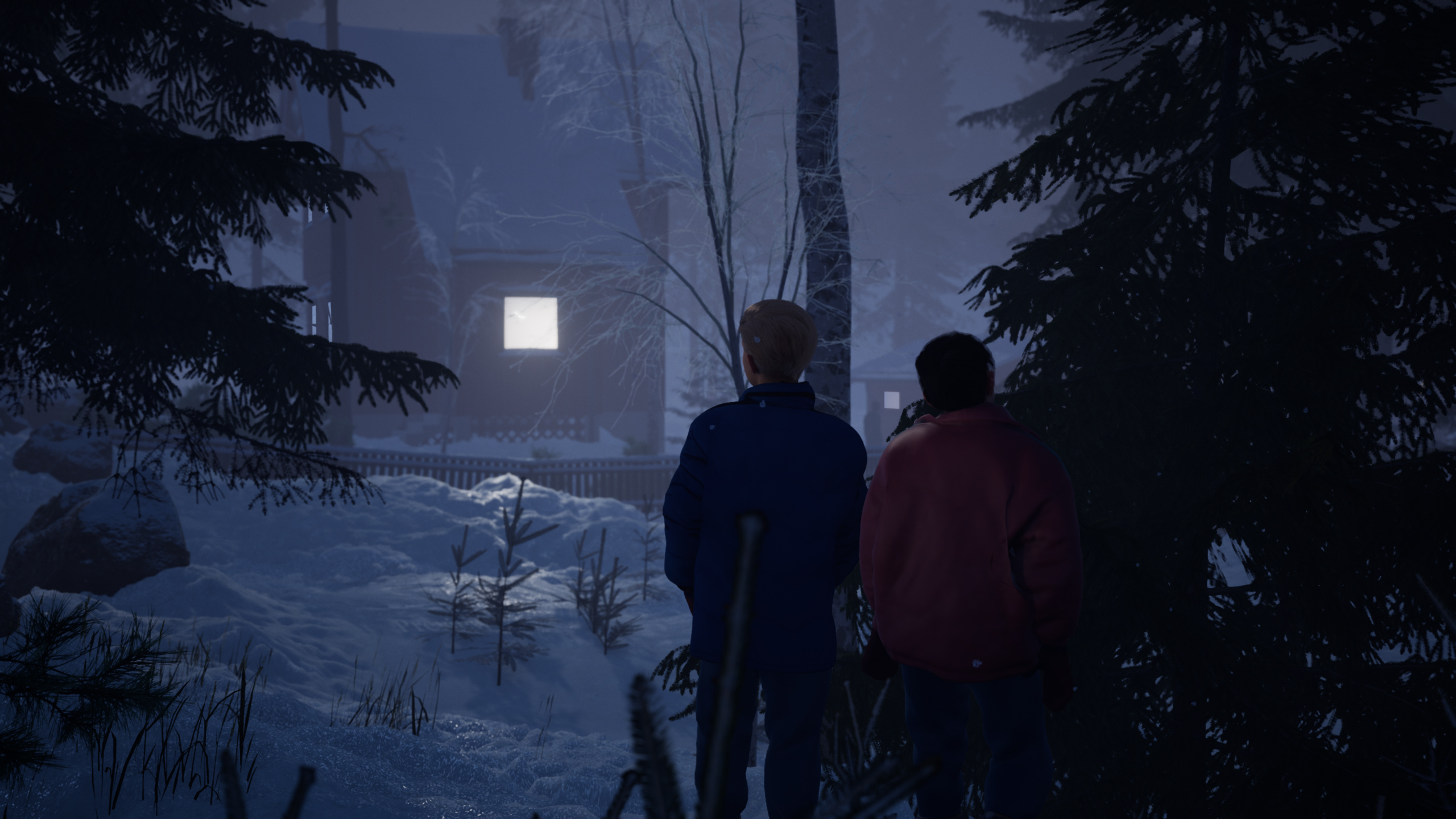

In the meantime, the short demo build gives us an idea of what we can expect to find later in the game. That ASCII-inspired 'dream world' will feature again elsewhere, albeit via much faster transitions, as Oskar gradually gains new powers to hack objects in the town. In one set-piece, he'll be charged with helping his (apparently well-heeled) friend Eva abscond from her parents' mansion, opening security gates and switching off cameras so he can sneak in and break her out.

The juxtaposition of the two worlds is striking, and Nielssen believes that contrast is key to the game's appeal: on the one hand, you have a very contemplative, contemporary narrative adventure that's all about exploration and atmosphere, and then a blast of retro- feeling action. "It's almost as different as you can get," he says. "The idea is that this is a very gamey, arcade-style space, with 8bit music. Some of the more complicated machines will have antivirus, which turns it into a bit of a boss fight, and that's what you need to get through to complete the hack."

There's a story explanation for why the hackspace is so game-like, though Nielssen suggests it would be a spoiler to say why. Then again, we wonder if we already know a little too much. An ominous tower looms over the town; this, Nielssen says, belongs to a government special-forces agency, which has shown up looking for some AI software over which it's lost control. It doesn't take a giant leap to imagine how this might be connected to Oskar's dreams.

Then again, as Loeding has already demonstrated, there's more to Last Days Of Snow than meets the eye, and it's fair to expect the same from the script, developed by Nielssen in collaboration with writer Nathan Hardisty. "Making a good story is a long, long process," Nielssen says. "It feels a bit like archaeology. You dig carefully around it and sometimes you don't really know what you have until you've developed the whole thing."

You could say the same for making games, of course. The next step for Loeding, Nielssen says, is GDC, and developing the demo further into a more substantial vertical slice. The one thing he's keen to avoid is over-scoping, and letting development drag on needlessly. "I'm not out to make this a ten-year process," he says. "We want to be able to ship it and learn from our mistakes for the next project." Unlike the blanket of white covering the town, then, Last Days Of Snow may not be pristine. But it's hard not to admire this pioneering team as it takes its first steps into untouched territory.

For more, check out the big new games of 2020 on the way this year, or watch the video below for a guide to GamesRadar's favourite games of the past decade.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.