Fistbumps, violence, zero dialogue. But Doomguy is the smartest player character around

All games are immersive to some degree. That’s the very nature of interactive entertainment. But it’s the degrees that matter when it comes to designing a lead character. Do you want your protagonist to exist slightly outside of the player, behaving as a combination of movie hero, buddy and wing-man? Then you’re going to need dialogue, actors, and a very specific vocal performance. Yours is the path of Nathan Drake and Marcus Fenix. And that’s fine.

But if that’s not for you, then you probably want to relate the game experience more directly, with the player as the lead character. And that is very distinct experience of its own. It’s the difference between taking a guided tour of a new city and exploring alone, basically. The former might make for an initially easier, more comfortable trip, but you’ll often find yourself feeling more involved and connected to your surroundings if you go it alone and make the journey entirely your own. And some games need that.

Neither Dark Souls nor Bloodborne would be half as resonant if their perilous, risky explorations of the unknown were conducted by a chatty action figure with his or her own, separate agenda. The danger, bravery and reward that those games thrive on would be grossly diluted if filtered through a third-party participant.

On a similar note, Nintendo’s Shigeru Miyamoto once revealed that the essence of the Zelda series was inspired by his early trips to New York. On those initial visits, he would go exploring on his own, gaining a great deal of gratification from carving his own path, progressively learning about his environment, gaining new tools such as maps or a hired bicycle, and using it all to forge a more personal, self-made journey. As such, it’s perhaps not a coincidence that Link has remained steadfastly silent for 30 years, a conduit through which the player explores Hyrule directly, rather than an embedded personality with predefined place in, and knowledge of, the game-world.

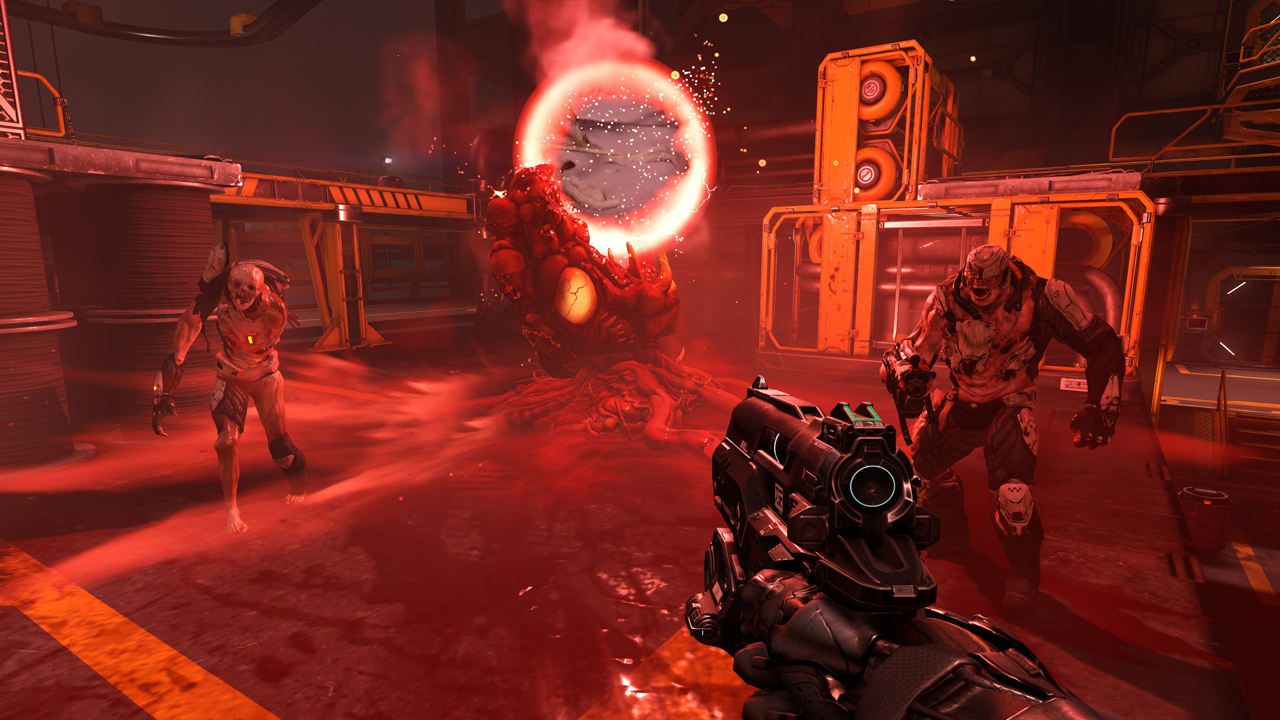

And while Doom 2016 is no open-world adventure – though its nonlinear levels do contain a notable amount of player-led exploration and discovery of their own – its use of a silent protagonist focuses those same values in a slightly different direction. Because while Doom is ostensibly a ferocious, fast-paced, first-person shooter, it’s also a game that has player expression at its absolute core.

In fact, more than that, personal expression and creativity are the combination key that unlocks the game’s greatest levels of fun and success. Doom’s combat is so organic, its demands so ever-changing, its opposition so reactive and its moment-to-moment action so fundamentally written and rewritten by the game’s immediate responses to the player’s presence, that it’s a canny move indeed on Id’s part to ensure that the player feels at once entirely inserted, and encouraged to play in a way that incites the optimum, most unapologetically Doom results. Systemically, Doom is a game about throwing rocks into a pond and then surfing the ripples that come back, and so it wants you to be hurling boulders at all times.

Here’s where Doomguy’s characterisation comes in. Because he has a lot of it. Or rather, he has exactly as much as he can carry without ousting the player as the primary presence in the game. Right from the start, he’s encouraging and indicating the kind of behaviour that will serve you well. Gleeful, flagrant aggression. A lack of respect for those who would oppress him, or who would even just be foolish enough to attempt to direct him. Attack as a first response, without second thought or self-conscious doubt. A resolute sense of doing what he has to do, but doing it his own way.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

He has to follow certain mission objectives, of course. That’s just how video games work. But he never feels in thrall of the world’s rules, and that means that the player never feels restrained or intimidated either. Doomguy’s journey is his own, to smash the crap out of as and how he sees fit, and anyone else who gets involved will be useful when convenient, and ignored when not. His disregard for those who, in any other game, would become a close ally or trusted superior, swiftly translates into an unshackling of the player’s sense of ‘how these things work’. There are no rules. You’re in charge, whatever anybody else says, so just go out there and be you as hard as you can.

It’s there at the start, in the way he smashes that communications monitor out of the way, mid-message, as soon as he’s learned all he needs to know in order to do what he wants to do. It’s there when he off-handedly decides to wreck energy production for the whole galaxy, after completing the objective he’s supposed to be carrying out, because the process is corrupt and no-one can stop him. It’s there when he quietly saves a copy of the UAC’s VEGA AI when shutting the whole system down, uninstructed and for reasons not yet known. It’s in the tone of every incidental animation, when he punches a power button instead of pressing it, and swipes hard across touchscreen control panels like he’s slapping them in the face. “Rebel”, says Doom. “Destroy anything in your way. Smash anything that even threatens to be a problem. This isn’t their story, it’s yours”.

And it really is. Because here’s where we hit the next level. Because once Doom has taught you to be brazen, aggressive, and ‘hey, why not completely ignore that objective for an hour and go exploring this labyrinth for secret stuff instead’, Doomguy’s continued, belligerent lack of interest in being anything other than Doomguy ensures that he remains a potent conduit for immersion and empowerment whoever you might be.

See, the thing about Doomguy’s characterisation moments is that they’re all incidental, not explicit. There’s a huge amount of distinctiveness and drive there, but through their ambient delivery, they are as unobtrusive as they are quietly all-pervading.

Doomguy doesn’t come with any bullshit. He doesn’t come with any baggage. He doesn’t have family drama, or personal angst, or regrets over his relationship with his old best friend. He has no agenda but the same one you have: Journey through Doom, kill the living shit out of every demon he sees, have a great time doing it. He has no thoughts of the past, or in fact any thoughts of anything beyond the immediate right-here, right-now of doing what needs to be done, and doing it well. He’s pure and in the moment. He’s less a person, more a primal, distilled force of just fixing shit by getting right to the point. He doesn’t even have a name. He’s the playable Everyman, but one with a distinct direction. He’s action. He’s immediacy. He’s cause and effect. He’s a personification of Doom’s entire gameplay philosophy.

The real upshot though, is that all of this means there are no barriers between Doomguy and you, so there’s nothing getting in the way of Doomguy being you, at your most focused, effective and forthright. Yes, we know that he’s a man. And at the very start we see that he’s white. But once the full-cover armour’s on – armour which diminishes the importance of his personal physicality, head-to-toe, and then becomes a defining trait of his wrathful persona in the game’s own lore - all of that goes away, superficial trappings replaced by unsullied attitude and intent. There’s nothing but the here and the now, and the ripping and the tearing, and making sure that the necessary work gets done to the extreme.

All of this is wise. Because any extraneous personal crap would ground Doomguy somewhere else, away from where you are and what you’re doing. Anything, however small or tangential, would be painted by the values or conceits of someone specific, someone who isn’t you. Someone of a different gender, or ethnic background, or social scene. And that would devalue all of the important attitudinal encouragement the game does. Whatever was happening in the immediate, Doomguy would be from somewhere else, and have other concerns. And that’s not what Doom’s about. Doom’s about you. Heck, without a voice actor, Doomguy can’t even alienate you by grunting in the wrong way.

This sense of ambient empowerment, open to all, is further bolstered by the game’s more explicit narrative set-up. Progressive lore seeds hints that Doomguy might be much more than a normal Marine, and a true scourge of the forces of Hell – but crucially, this is still relayed with ambiguity, not forcing anything upon the player’s own sense of who he is. And going a step further, the sparse NPC cast – consisting really of only two other ‘human’ characters and an AI – is smartly balanced so as to not intrude, either by an excessive presence or ideological baggage. There’s one man and one woman, both by and large gender-neutral in terms of stereotypical characterisation, and both presented with abstracted, cybernetic physicality to further reduce real-world preconception and expectation. And VEGA? It might externalise with a heavily modulated male voice and occasional holographic figure, but it never really even approaches humanity, let alone anything else.

Of course, Doom is hardly the first game to use a silent protagonist to increase immersion, but the difference is that its iteration of the idea is not just a microphone for your own voice, but also an amplifier for a particular part of your personality, the part that can really relish and revel in what the game is all about. It subliminally encourages you to sing with exactly the right pitch and tone, and it lets you think it was all your own idea.

The song will be yours, of course, as you freewheel through the slaughter, switching from rockets, to plasma, to buckshot and back while steadfastly refusing to give the growing demon horde an ounce of fear or respect. But it’s Doom that pushed you out onto that stage, and it’s Doom which is giving you all the right cheers and woops in order to keep you in the zone. The roar of that ceaselessly enthusiastic crowd is one hell of a motivator.