Cyberpunk 2077 proves once again that video editing makes for a great game mechanic

From Detroit: Become Human to John Wick Hex, games are full of tributes to video editing software

Martin Scorsese is nothing without Thelma Schoonmaker; Brian De Palma wouldn't have changed cinema without Paul Hirsch, nor Spike Lee without Barry Alexander Brown. Great film directors are only as good as their equally great editors - the people who take the raw footage, select the best shots, and determine the sequence that will deliver as much tension, momentum, and emotional heft as possible.

Much has changed in the far-flung future of Cyberpunk 2077. Film has been replaced by braindancing, a full-sensory experience that grants a user access to the recorded thoughts, memories, and feelings of another person. But even in Night City, that same old rule holds true.

Yes, the braindance studios need employees crazy enough to go out and find trouble - to get involved in the most dangerous and exhilarating situations they can find, and bring those recordings home. But just as crucial is the technician who edits that footage for the viewing audience.

"After all," wrote Colin Fisk in the Cyberpunk sourcebook Rockerboy, "who really wants to feel how the hero waited twenty minutes just to get transportation to the airport?"

And… cut!

With its upcoming game adaptation, CD Projekt Red has put the spotlight on the often-overlooked editor - and drawn on the video editing software that Fisk and his fellow Cyberpunk writers could only dream of back in 1989.

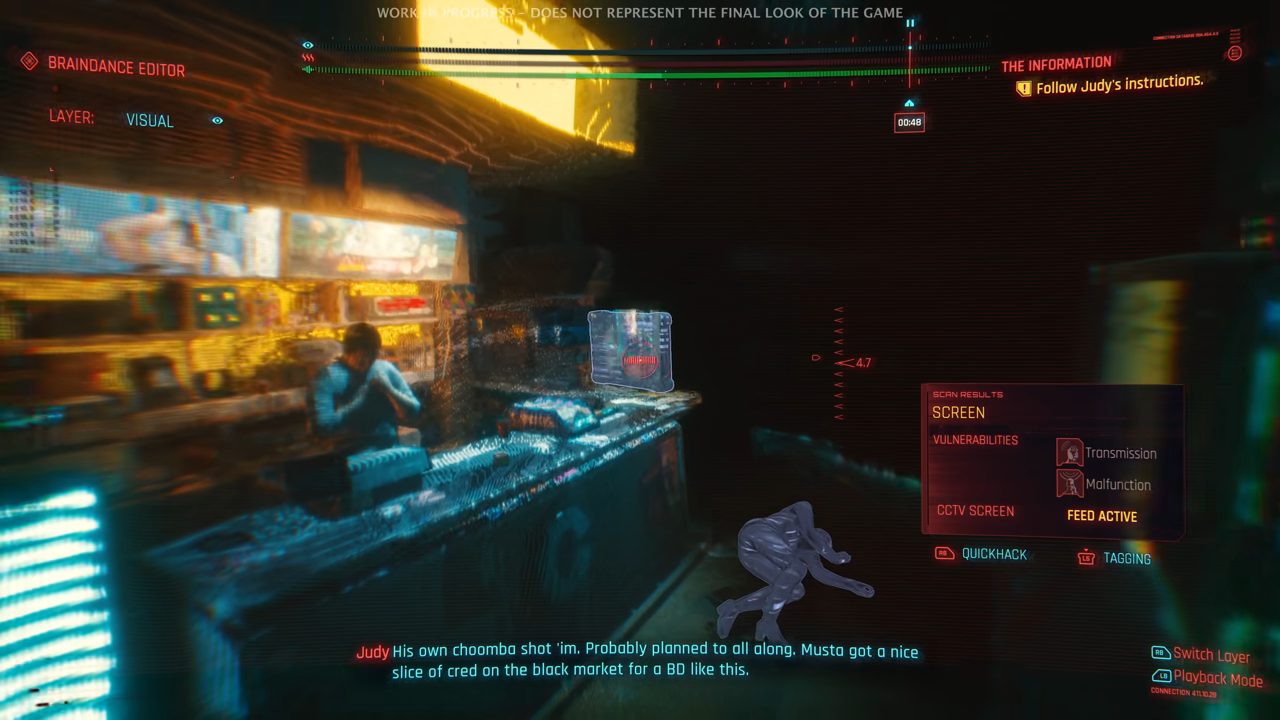

When players are first introduced to braindancing in Cyberpunk 2077, it's with a simple playback. They watch an adrenaline-soaked robbery of a corner shop, in which the frantic perpetrator assaults a customer, grabs cash from the till, then succumbs to a slug from the gun of an unseen assailant. It's the kind of footage studios pay well for: grotty and transgressive, with a taste of the final sensations that come before death.

When the player next jumps back in, though, they're given a free camera to zoom around the same scene, observing it from any angle. They can freeze, rewind and fast forward, or switch to an audio layer and isolate background noise for close listening. In other words, they're playing with tools deeply reminiscent of real-life video editing - simply because they're fun to mess with.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"I think people inherently enjoy telling and retelling stories, and with the right constraints and abstraction of an editing toolset, it easily transfers to games," Bithell Games' Nic Tringali tells me. "It's a way to interact with the game that's relatively easy for players to understand, and that produces a different kind of engagement with the virtual space."

Hands-on with Cyberpunk 2077: Freedom, master world-building, and customisable genitalia

In Cyberpunk, editing mode is an investigative tool, used to search scenes for subtle details to scan. By tapping into a surveillance camera in that corner shop, players uncover that the perp's killer is the same friend who handed him a gun to hold up the store in the first place - an unscrupulous director looking to increase the value of his braindance recording with a thrillingly morbid ending.

It's a mechanic with plenty of recent precedent in AAA gaming. Watch Dogs was founded on the idea that observing a scene from the right angle might reveal more about it. Detroit: Become Human asked its robocop protagonist to close cases by rewinding and scanning 3D footage, just as players do in Cyberpunk. In fact, the idea goes back further still, to the ironically forgotten Remember Me, from Life is Strange developer Dontnod. In a world where memory has become a commodity, players rewind through scenes and tweak the props to bring about different outcomes - like Francis Ford Coppola improvising an ending for Apocalypse Now.

Cyberpunk might not allow you to change the events of its recorded stories, but it does let you reframe them by discovering new perspectives. "The game is not only telling you a story and inviting the player to interact with it, but also to have a hand in retelling that story inside the game itself," Tringali says. "I think that's secretly quite powerful."

Another perspective

Tringali didn't work on Cyberpunk or Remember Me, but he too has taken inspiration from video editing. As a designer on John Wick Hex, Tringali was responsible for the game's timeline - a way to visualise the order of martial arts attacks that looks uncannily like Adobe Premiere.

"There are only a few ways to show multiple blocks of varying length all bound to the same time system," Tringali says. "It was a conscious effort to keep the timeline clear and simple, while still communicating the information that only it could achieve. Looking at video editing was useful, such as the timecode and the way action blocks are divided."

Timecode gives you the number that tells you precisely where you are along a timeline - it's how video editors synchronise different parts of their work. In John Wick Hex, it tells you how long you've got to dodge a bullet to the chest.

"The goal is for the state of the action around you to be easily read by the player," Tringali says. "They can immediately sort in their minds who presents the highest threat, and see how their actions will play out against them."

"I think people inherently enjoy telling and retelling stories"

Nic Tringali, Bithell Games

The fights in Hex pause between actions, giving players regular opportunities to analyse upcoming events in the timeline. "Being able to quickly compare when your actions will start, end, or execute relative to the enemies around you is an advantage," Tringali says. "Much of the game is risk assessment."

Judy, the Cyberpunk 2077 character who runs a braindance suite in Night City, tells you to think of editing mode as your "own little sandbox". But it's clearly more than that - video editing has become the inspiration for a whole range of game mechanics that pull on both the detail and precision involved in the trade.

"There's an appeal in unraveling a story in your own way, such as in games like Her Story, Outer Wilds, or Return of the Obra Dinn," Tringali says. "For both designers and players."

Perhaps soon, if the trend continues, gamers will remember to say Schoonmaker's name alongside Scorsese's.

Excited for the game and want to reserve a copy? Then be sure to take a look at our guide on all the best Cyberpunk 2077 pre-order prices.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.