Revisiting Blood Gulch - Halo's greatest ever map?

Over a decade ago, a relatively unknown machinima outfit produced a short video made in Halo: Combat Evolved. In it, two Spartans had something of an existential dilemma. “Why are we out here?” asked one. “It’s just a boxed canyon in the middle of nowhere, with no way in or out.” Those Spartans were the nascent stars of what would go on to be the phenomenally successful Red vs Blue. The canyon was Blood Gulch.

Every first-person shooter has the map that defines it – a space so perfectly laid out that it captures and crystallises each game’s unique potential for dynamic, engaging conflict. The asymmetrical, real-world sprawl of GoldenEye’s Facility was perfect for stalking opponents with one-shot pistols in Licence To Kill mode. The deathtrap central hallway in Counter-Strike’s Dust nonetheless exerts a gravitational tug on nearby players, with its tempting routes to both bombsites.

Even Black Ops and its sequel have Nuketown, a cramped, incoherent killing field whose popularity says more about its playerbase’s tastes than the strengths of Call Of Duty’s smooth, precise gunplay. For Halo, however, the defining map remains Blood Gulch. Far from the tightest, most immediately thrilling space in the series – that honour should probably go to Halo 2’s Lockout, and its intricate overlapping sightlines – no other map at release showcased Halo’s nature as well, its wonderful ability to segue in and out of tense firefights and moments of ridiculous slapstick, just like this unassuming, dust-blown desert canyon.

Halo broke rules. The combination of first-person shooting and third-person vehicular sections might be practically taken for granted today, but in 2001 it required a different approach to map design. Prior to Halo, multiplayer map design usually tended towards the boxy interiors of GoldenEye and Quake – clearly designed to human scale, and constructed from mixtures of corridors and open spaces.

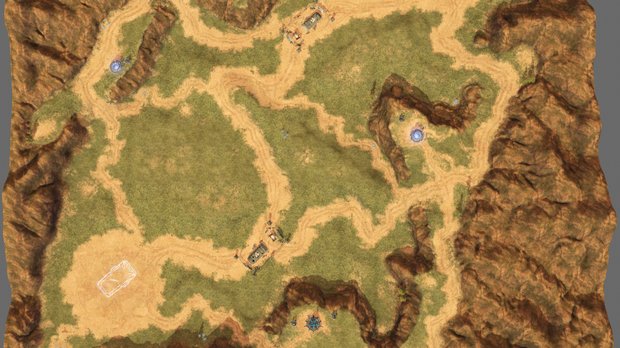

Blood Gulch is a canyon, however, a vast expanse of undulating landscape and scattered pieces of natural cover with a base at either end. The valley is broadly symmetrical, as maps need to be in order to ensure balance in team-based gametypes. But as with twins, stare closely enough at the two ends of the valley and you’ll be able to tell them apart. Along with subtle variations in the bumps, crests and ditches that run across the length of the map, there are more prominent tactical nuances, too. A ridge overlooks the Red Base – the Red Team can reach it nigh-on instantly, but they’re also more vulnerable to sniper fire should a crafty opposing player perch there. Conversely, the Blue Team has more immediate access to a tunnel system running along the sides the map, but needs to watch for ambushes from the caves, which can disgorge a Red Team to their door. These subtle instances of lopsidedness compound the organic feeling of the map, yet they’re carefully calibrated not to disrupt the balance.

The bases are where you’ll find traditional FPS gunplay. Each has two entrances, an open ceiling and sloping paths to the roof. Death can come from behind, in front and above you in these cramped structures, and that naturally encourages the most crucial thing in an online game: motion, in this case a circulating movement in and out of the buildings. Players who make it to the top of the base can effect quick getaways, too, thanks to teleporters located on the roof of each structure that immediately transport you to the valley.

This is no-man’s land, a vast landscape with little cover that a Spartan on foot is ill-equipped to traverse, especially if there is a sniper perched on the opposite base. The strange tension of Blood Gulch emerges from just how dangerous the majority of the map is for players not in a vehicle: this open, indefensible terrain forces players to shepherd themselves back into a base, the cave systems, or a nearby vehicle. And that means firefights are normally fought in cramped, intense conditions despite the ostensible openness of the map. And yet that landscape is perfect for hurtling across in a Warthog, the enemy team’s flag strapped to your back. The open space is ideal for high-stakes sniper duels, too, or battles fought between a lone wolf with a rocket launcher and a team sitting snugly in a tank.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

And that’s why it never went away. Halo 2 practically ported the map via Coagulation, a near-identical battleground that installed a pair of banshees in the bases’ basements. Halo 3, meanwhile, had a spiritual successor in Valhalla, a more verdant, cramped arena that solved the problem of the centre of the map being so dangerous for players out of vehicles: rather than teleporters, Valhalla uses Man Cannons to fling players to the centre of the arena, where firefights will naturally ensue. Valhalla so perfectly fulfils Blood Gulch’s role in the map rotation that Bungie refused to remake the latter for Halo 3, although with Halo: Reach and the Master Chief Collection the studio finally relented allowing players to experience Halo's greatest ever map once more.

Perhaps the most fitting tribute to Blood Gulch came with Halo: Reach's Haemorrhage, identical in layout to its earliest incarnation but now wearing Valhalla’s lush, green clothes. It was introduced in a special episode of Red vs Blue, as part of a joke that saw the characters tricked into thinking they were headed home. For those of us who had spent hours perched on the roof of those bases, aiming down a sniper’s scope, it wasn’t a joke at all.

Read more from Edge here. Or take advantage of our subscription offers for print and digital editions.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.