We could keep you here forever: Superhot explores the dark side of VR

You won't have to dig very deep inside the time-bending first-person shooter Superhot to find a ton of weird stuff. The game boots like a futuristic, VR-version of an early-90s IBM PC, complete with DOS-inspired loading bars, text, and the sound of a hard disk whirring away in the background. You can go right to the meat of it, chipping away at levels in which time only moves when you move, shooting crystalline enemies and watching them shatter into a million glorious pieces which hover in the air until you take your next step. Or you can poke around its folders looking for something else lurking in the digital shadows of this fake computer.

Vote for Superhot in the Best Visual Design and Best Indie Game categories at the upcoming Golden Joystick Awards 2016 and claim three games for $1 / £1 for taking part.

Strewn amongst the weird 'demoscene' programmer art and chatroom programs is a folder labelled 'Videos'. Inside that folder is a file labelled 'rsm.avi'. Booting it up streams a video compressed into barely discernable ASCII-like characters, as a robotic voice reads off ad copy for a brand new VR game. His words make it sound like a grand ol' time, but everyone in the video is screaming bloody murder and convulsing wildly, as if the game is ripping their brain out through their eyeballs.

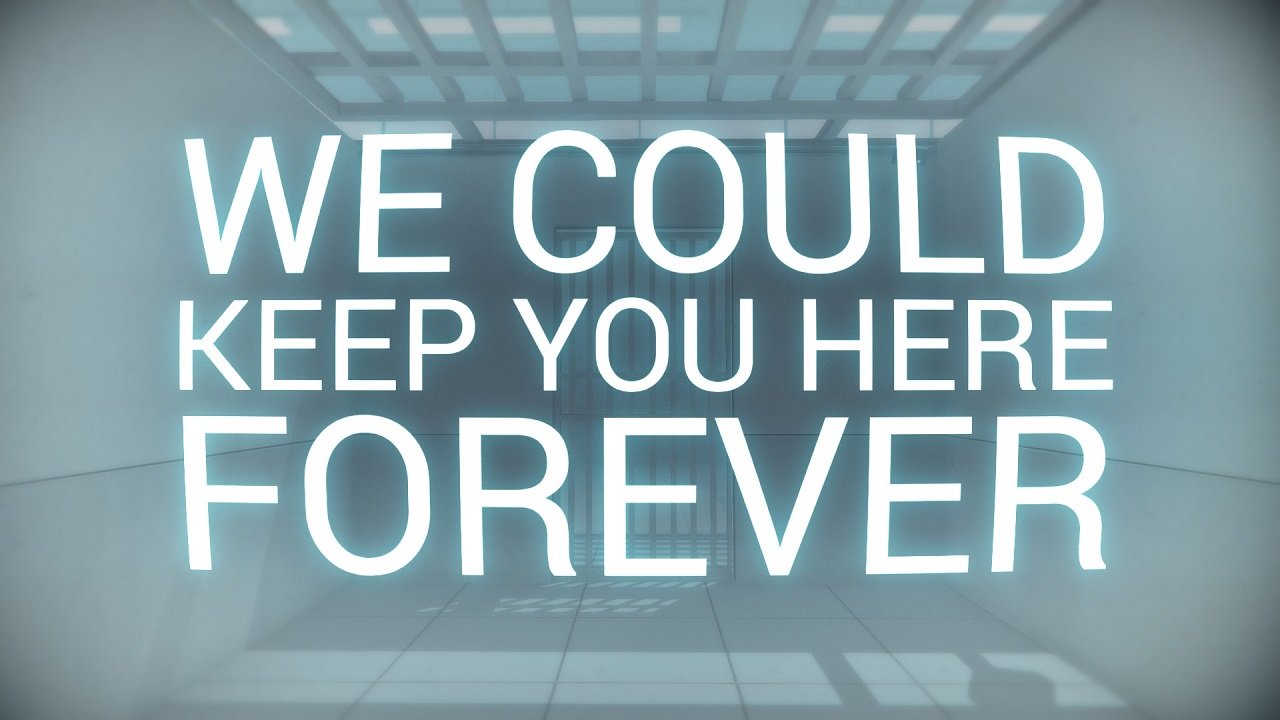

It's an interesting video to include, seemingly out of nowhere (turns out it's actually a video ad for an April Fool's game created by one of Superhot's developers). It's kind of funny to watch, but it's also deeply disturbing, and Superhot's pixelated distortion of the video somehow makes it so much creepier. That's the kind of game Superhot is, though, riding the knife edge between comical farce and ominous vision of the future. Right now, it's not actually a VR game (though Oculus support is coming later this year), but it's pretending to be one, complete with screen-filling loading animations and a bizarre sense of immersion created by thrusting you deep within the meta-layers of its plot. And while so many game developers and publishers espouse the limitless future of virtual reality, Superhot seems to be the only game wondering if there's a dark side to VR that no one wants to acknowledge.

"Well, The Matrix is the obvious choice," art director Marcin Surma tells me when I ask him where Superhot's influences come from. The 1999 sci-fi classic certainly evokes similar feelings that Superhot does, with its emphasis on highly-choreographed slow-motion fight scenes and a mind-bending story following a group of humans as they escape a VR prison designed to look like real life. He also cites films like Chan-Wook Park's Oldboy, David Cronenberg's Videodrome, and a music video for Biting Elbows' 'Bad Motherfucker', directed by Ilya Naishuller, which shows all of the action from the point of view of the main character, like a first-person shooter (Naishuller is also responsible for the upcoming feature-length POV film, Hardcore Henry).

While videos are typically passive experiences, 'Bad Motherfucker' puts your right into the shoes of its protagonist thanks to the camera mounted on the actor's head, immersing you in the experience in a way few movies have. The effect is not unlike virtual reality - exciting, intense, and more than a little disorienting at first, just without the headset. "It's very Superhot-y," Surma says, and as you watch it, you can see the germ of many of Superhot's coolest moments - jumping over the roof of the car, dealing with multiple enemies in confined spaces, nailing that perfect shot - in the music video.

Superhot pulls much of its action elements from Naishuller's work, but it's Videodrome that's responsible for the sinister current that runs throughout the game. Cronenberg's cult horror classic follows the story of a Canadian television executive looking for the next hit show, finally stumbling upon the titular hyper-violent program. The only problem is that the show has the added side effect of warping the real-life perception of whoever watches it, ultimately taking over their mind.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

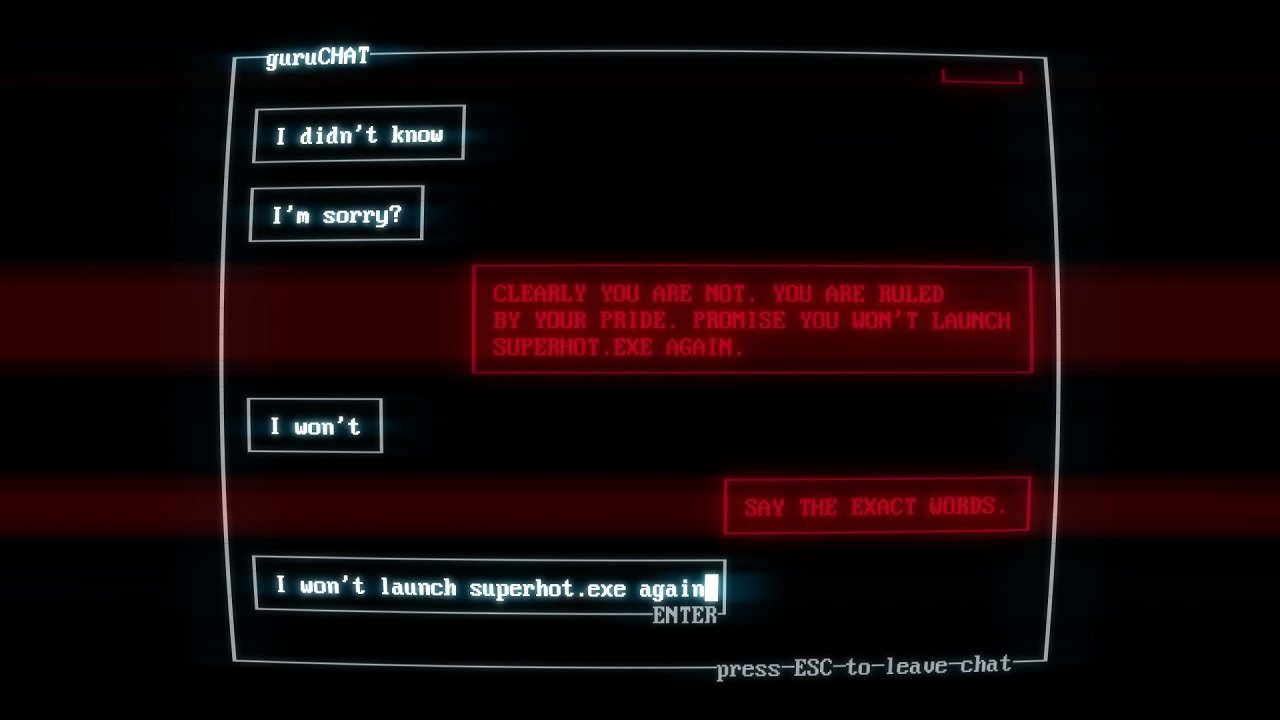

You can see the parallels instantly when you start playing Superhot for the first time. Superhot isn't just the name of the game that you're playing; it's the name of the game within the game, illegally downloaded onto your VR-enabled PC from some sketchy website. As you make your way through its levels, figuring out how to solve its time-based shooter puzzles, you start to discover that Superhot might be responsible for some terrible events that you're hearing about on the in-game IRC channel. That the password you typed in to crack the rest of the game was magically provided for you. That the words flashing on the screen aren't just tutorials, they're a form of mind control. That the red, texture-less enemies you're killing in the game might not be virtual at all.

This feeling that you might be losing control the more you play it is tied right into its core design, too. You'll notice when you start a level, you're given a brief command: "You missed. Throw your weapon." The only way out of this situation is to heave your gun at the enemy inches in front of you, take his weapon, and shoot him, and only then are you let loose to finish the rest of the stage as you see fit. But it's a constant back and forth, as one level gives you a ton of freedom and the next puts you in a prison cell where the only way out is to follow the directions given to you by the program - or whoever is really running the program on the other end of the server. "We wanted to do something with this," Surma explains, "especially in a video game, because video games are all about giving the player freedom and empowering the player. When you have a game that empowers the player and at the same time casting the player as a puppet, it's something I believe is… interesting."

And you're very much a puppet when you play Superhot. You know you shouldn't be playing it - or, you shouldn't be playing the game-inside-the-game, at any rate. You found it illegally. Cryptic messages warn you at every turn. Every instinct is telling you that continuing down this path will only lead to your ruin. And yet, through its simple-yet-layered design and the intriguing nature of its narrative, you are compelled to continue falling down the rabbit hole. It echoes a lot of the same fears we've seen in the movies of the last few decades which show off the hypnotic allure of virtual reality and the unlimited promise of its digital worlds.

Surma isn't really sure what the future holds for VR, whether it's simply going to be another gaming platform or a brand new obsession for humanity. "It's so ingrained in your head that virtual reality is something that's going to be a drug-like thing," he says, "that people are going to be in virtual reality and it's going to cyberpunk-ily seep into their minds. In real ways there are going to be people who are addicted to it. This is something I think is quite possible, because people can already be addicted to video games, so this is just another avenue, and maybe even a bigger one."

Superhot definitely plays into those fears in the same way films like Videodrome or The Matrix has, but for the first time in human history, that technology is at our fingertips. It's not quite mass market - even PlayStation VR's $400/£350 price tag is a huge asking price for many - but it's way more affordable than those Dactyl Nightmare set-ups you'd see in shopping malls two decades ago. And the prospect of having a device that immerses almost all of your senses available at a moment's notice is as exciting as it is terrifying. We're headed into uncharted technological waters, and it's impossible to say what lies on the other side.

It's ironic, then, that the team is working on bringing Superhot to the Oculus Rift sometime in 2016, in addition to porting the game to Xbox One in the coming weeks, as well as developing free additional content to be released in the near future. But then again, Superhot is filled with ironies like these. And why not? Might as well have a self-aware chuckle about it now, before some future VR game controls our mind for real.