Portal 2 almost had fake endings, terrible multiplayer and no portals

Writers Erik Wolpaw and Chet Faliszek reveal the things that got left out of last year’s GOTY

One by one, the tables recede slowly into the boardwalk. Seconds later, the trees do the same. The lights flick off, then on again, and as the water drains from the “ocean,” you realize that the sunny sky was just a projection; you’re a prisoner some kind of huge, soundstage-like room. As you watch this helplessly, the walls suddenly close in, leaving you trapped in a tiny, transparent cube. This cube is then pulled through a doorway by some kind of armature, into darkness.

That, as shown at the GDC panel “Creating a Sequel to a Game that Doesn’t Need One,” was the original opening for Portal 2. It seems that, in the years between Portal and its sequel, a lot got left on the cutting-room floor, and Valve writers Erik Wolpaw and Chet Faliszek were more than willing to share. Interestingly, the original vision for the sequel called for three of its most iconic things to be removed: Chell, GlaDOS, and the portals themselves.

“We decided to keep Aperture,” said Wolpaw. “Aperture Science seemed kind of like it was the foundation on which Portal was built. From a writing perspective, we thought there was sort of unlimited potential there to explore this mad funhouse of science. So, having decided to keep Aperture… we cut Chell. She got out, good luck to her. Who needs her? We cut GlaDOS. She kind of died in the end, and she had a nice little story arc; time for a new villain. And we cut portals. The name is in the title, but we figured we’d worry about that later.”

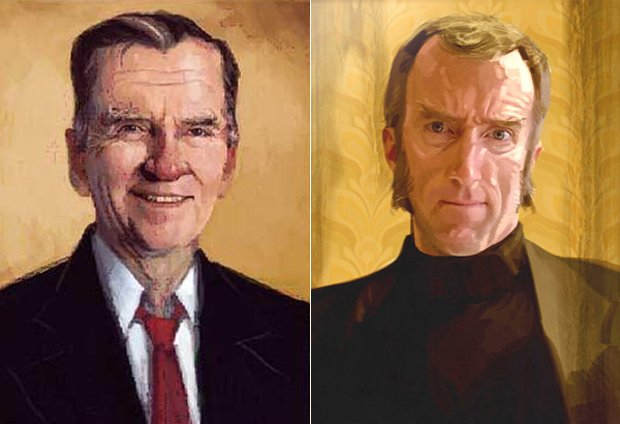

The plan, Wolpaw said, was to replace the portals with a new mechanic that had come out of Valve’s design experiments, called “F-Stop.” (And while Wolpaw described F-Stop as “sexy,” he stopped short of actually describing it, as it may be used in a future game.) The new villain, meanwhile, would be Aperture Science founder Cave Johnson, originally envisioned as a crazy Southern billionaire.

Above: One of the original concepts for Cave Johnson (left), with the final version at right

“In F-Stop Portal 2, [Johnson] was the whole show. He was the main character,” Wolpaw said. GlaDOS, meanwhile, would have appeared only as a little wheeled robot known as the Gyroscopic Liability Absolver and Disk Operating System (referred to as “Betty”). Whenever Johnson would finish explaining a test, she’d trundle out to quickly rattle off a string of legalese meant to absolve the company of any liability.

Originally, Portal 2 was also going to be a prequel. Set in the ‘80s, about 20 years before the events of Portal, it would have focused on a robot uprising at Aperture (which also involved, according to pictures Wolpaw displayed, a giant chicken running through the offices at some point). After about three months of work, the game was ready for playtests. “The constant feedback we got was that it was a lot of things, but it wasn’t Portal 2,” Wolpaw said. “So, lesson one: you don’t need to burn everything to the ground.”

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Above: Bits of the 1980s Aperture concept did make it into the final Portal 2, though

GlaDOS and portals came back, but the team still didn’t see the need to revive Chell. “She’s mute, she doesn’t really have a character, she’s just kind of this physical presence that you occasionally see glimpsed through portals,” Wolpaw said, adding that, as writers, they felt her story was finished.

“We started this iteration of Portal with you waking up in the Relaxation Vault, and you were standing in front of a mirror so that you could see that you weren’t Chell,” Wolpaw said. “You were this other character we called Mel, who had blonde hair and a different-colored jumpsuit, and was pretty obviously not Chell. To a person, playtesters didn’t care… until the point where she wakes up GlaDOS, and GlaDOS does not recognize her.”

Above: This moment turned out to be far more important than the developers initially realized

It was at that point, Wolpaw said, that they realized Portal was about the intimate relationship players had with GlaDOS – and if she woke up and didn’t remember them, “it was actually a blow to the player.” So Chell went back in, too.

Beyond things that came out and then went back in, the panel revealed that Wheatley – the charmingly stupid sphere that acts as Chell’s guide at the beginning of Portal 2 (and who, it turns out, was originally envisioned as being voiced by actor Richard Ayoade instead of Stephen Merchant) – was, at one point, meant to be killed permanently when GlaDOS woke up. Instead of Wheatley, players would interact with six other spheres, including a paranoid one who surrounded himself with defense turrets (but pointed them all one way, enabling Chell to easily slip behind him with a portal, pluck him off his pedestal and bash him against a wall before dropping him down some stairs).

Also of interest was what Wolpaw called the “Morgan Freeman” sphere, a personality core that had been sitting in the same 20-by-20-foot space for several centuries, and was full of folksy, homespun wisdom about it – until you took him even a few feet out of the space, at which point his mind was blown, and he became useless. Eventually he found his feet again, Wolpaw said, although all of his wisdom and anecdotes would invariably relate back to 20-by-20-foot spaces.

As funny as that sounds, Wolpaw said that a lot of players ended up missing Wheatley, and that they didn’t spend enough time with the other spheres to really bond with them. So Wheatley came back, ultimately becoming one of Portal 2’s most important characters.

Above: And so, Wheatley's dramatic death by crushing was made less permanent

Not all cuts were character-based, and in fact several gameplay elements never made it to production. At one point, suction tubes were going to play a role in puzzle-solving, with players able to break them open and use portals to redirect the suction. Also, during co-op, GlaDOS would have realized that – as experiments with no human observers – her endless tests with the robots P-Body and Atlas were in a state of quantum uncertainty, like Schrodinger’s Cat. So in an attempt to make the bots more human, she would have sent them after human artifacts, one of which was a Garfield-parody comic strip someone had pinned up, called Dorfeldt (which was drawn by Anthony "Nedroid" Clark, and which we suspect evolved out of this somewhat-NSFW cartoon by Portal 2 writer Jay Pinkerton).

The Dorfeldt gag involved three panels in which Dorfeldt’s owner gets mad at him for eating all the lasagna. Neither GlaDOS nor the bots would have understood how that could be considered funny, and so GlaDOS would have added three more panels, in which the owner activates neurotoxin emitters and Dorfeldt reflects on his poor decision-making before dying.

Above: It's sad Dorfeldt didn't make the cut, but these two didn't really need much more humanizing

Originally, co-op wasn’t going to be Portal 2’s only form of multiplayer, and plans were laid out early on for a competitive version (which was labeled “Portal Kombat” during the presentation). “It was kind of a mix between the old Amiga game Speedball and Portal, except with none of the good parts of either of those two games,” Wolpaw said. “It was super-chaotic, difficult to tell what was going on, and no fun. The only real good news about this part was that we cut it pretty quickly and were able to use those resources to develop co-op a little more.”

At one point, Portal 2 was also set to feature several fake endings. “When we were watching Portal 1 playtests, there’s a part about two-thirds through the game where you ride an elevator into a firepit, and you’re supposed to escape the firepit, and that’s when you go behind the scenes,” Wolpaw said. “But a small percentage of playtesters were just fine with riding the elevator into the firepit. Like, that was a good ending for them. It was dark, but they liked it. So we thought, ‘we’ll service those people.’"

Above: Some people thought this was a fitting end to Portal. Weirdos

“We had these… parts where Chell would die, and that would be the end, and we’d play a song, and if you wanted to, you could just quit there,” Wolpaw said. “So we had one that was like two minutes into the game, and if you died there, there was just a song that… was just about reviewing those first two minutes.”

Later in the game, Wolpaw said, there was a point where you could see the moon overhead, shoot a portal onto it, shoot another one onto the wall, and you’d be sucked out into space and asphyxiate while listening to a sad song about the moon. (Wolpaw later said this was the sad song that played in one of Portal 2's Rat Man Dens, so it's likely he was talking about Exile, Vilify, which isn't about the moon but is pretty sad nonetheless).

Above: Here's a cool video of Exile, Vilify by YouTube user faceofdoomness

While they alternate endings went over well with playtesters, they were eventually cut, because of “how much work it was going to be for how little payoff, and partly because, other than those two, we had kind of overestimated how many great fake endings we were going to be able to come up with,” Wolpaw said.

The moon does play a role in the game’s actual ending, though, and it helped the writers come up a finale that was much better than the one they had originally planned. In order to break the game’s climactic stalemate, Chell would, for the first and only time, speak a single word: “Yes.” And while that sounds a little intriguing, Wolpaw did his best to assure the GDC crowd that it was horrible. “It was the classic idea… you have this great idea, and it sounds awesome! Chell’s finally going to speak. One word! And it’s going to be the one that ends the game,” Wolpaw said.

“Boy, did it suck,” Faliszek said.