Meet Kaare Andrews' 10-minute teen superhero, E-Ratic

A frenetic new hero coming from Andrews and AWA Studios

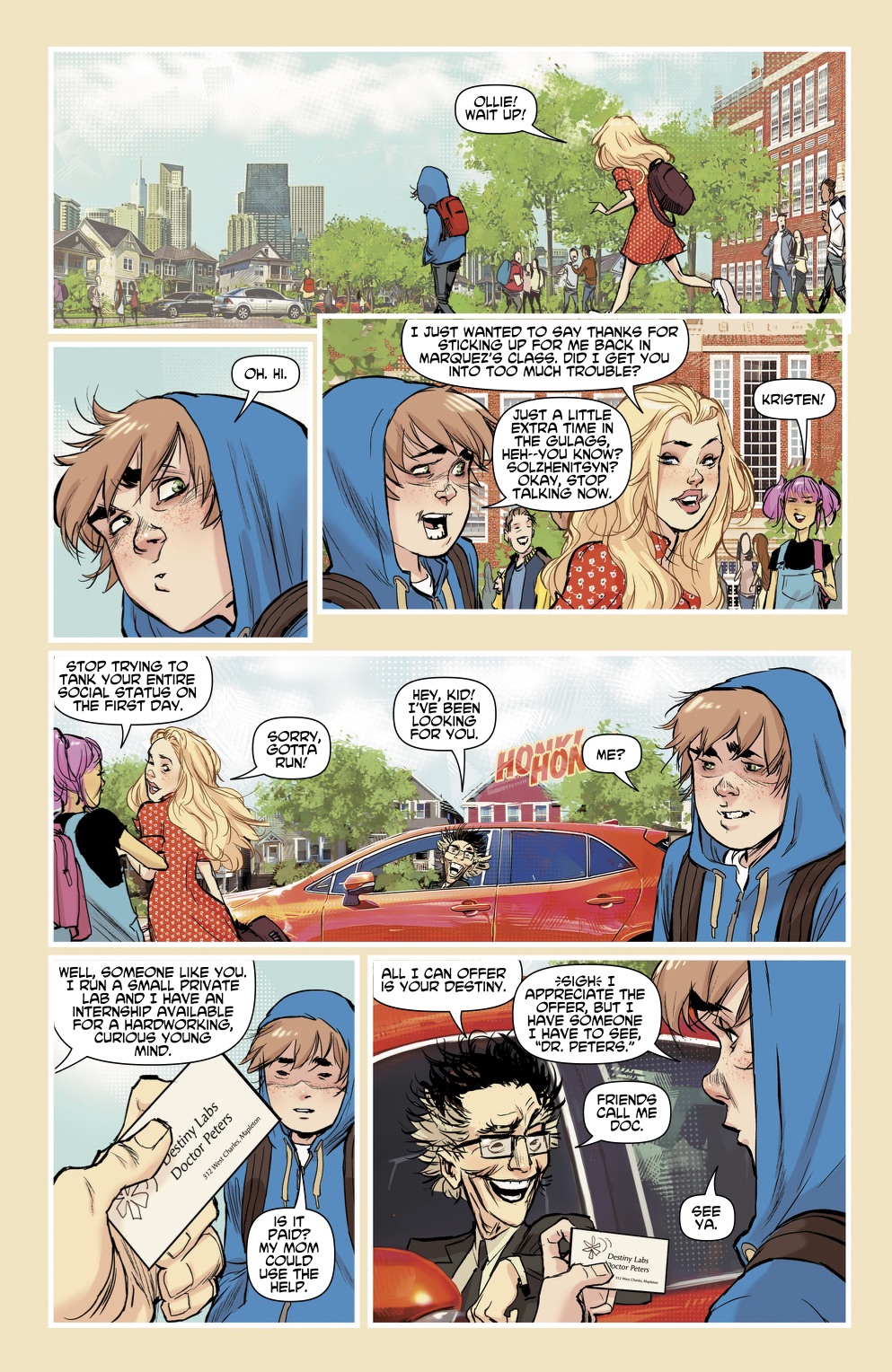

What if you could be a superhero (with superpowers and all), but could only do it for 10 minutes a day? Well, one superhero can - E-Ratic.

Kaare Andrews, well known for his vibrant and raw work on Marvel's Iron Fist, has created his own superhero - a fifteen-year-old hero who can only use his powers for ten minutes at a time, and must use the other 23 hours and 50 minutes a day to rest up.

Scheduled to debut December 2 from AWA Studios, E-Ratic is Andrews' second creator-owned superhero after Renato Jones, which starred in two solo series for Image Comics. Newsarama spoke with Andrews about E-Ratic, this unique take on superpowers, and the thoughts behind being a teen superhero.

Newsarama: Starting off, how did you get involved with AWA Studios, Kaare?

Kaare Andrews: The answer to this question is: Axel Alonso. Axel and I have been collaborators for decades. We both started at Marvel at the same time and we've had a great relationship. He's one of the best editors I've ever worked with and withstands the quirky way I approach making things.

In today's world, where everyone is on a trigger finger to destroy each other, it's important to support and stand by the people you love and respect. And what's more exciting than a new company? With new heroes? New readers? New stories and characters?

Nrama: How long have you been toying with the concept of E-Ratic? How did you pitch it to AWA?

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Andrews: I came up with a name, drew a cover, and wrote the tag line, '15 years old, 10 minutes to save the world.' And that was about it!

I mean, I knew that I wanted to create a high school character to exist in this new superhero world. And I knew I wanted a classic character. One that could exist in any era, a real archetype. Something you could see on pajamas or a t-shirt. And then I just sort of opened myself up to the universe.

E-Ratic just came out, whole cloth. The only change was I originally colored him yellow and grey... I sent that to Axel and immediately had the urge to recolor him red, grey, and blue. So before he could even respond, I sent him that different version.

My life is just too crazy to spend days and days designing and concepting... and as a highly creative personality, I actually distrust that sort of process. Anyone who exists in this field knows that creativity doesn't travel in low frequencies over long periods of time. It hits in sporadic, full blasts of lightning. It's your job to catch that lightning when it strikes.

I'm always looking for things that haven't been done before and the limitations of E-Ratic's powers is one thing that I haven't quite seen. Basically, he has the power cycle of a really bad cell phone battery. He has ten-minute bursts of crazy powers and then a 24-hour recharge cycle. Playing with these kinds of limitations just unlocked a whole set of story scenarios and I immediately started writing down all of the horrible situations that would create for him.

Visually, I've been sort of waiting my whole life for a character to put a hood on, but my favorite part of E-Ratic is his 'tail'. I haven't seen a tail done well on a character since Nightcrawler.

Nrama: That character is reluctant superhuman Oliver Leif, who's just 15 when we meet him. What attracted you to doing a teen superhero story?

Andrews: Nothing's really attractive about doing a teen superhero story. When you put it that way, it's entirely uninteresting. But a character who happens to be in high school? Sure - that's just a relatable scenario. I've done a handful of stories set in that world including Iron Fists with Pei and when I created Mangaverse: Spider-Man. What I like about a teen is that the journey of becoming a superhero is a direct metaphor for the journey of becoming a man. Facing new situations, unlocking new powers, and finding your personal responsibilities within that framework.

And once I set him in high school, I began to realize that there just aren't any stories out there that reflect what that experience has become. School's changed.

I stumbled across Pink Floyd's music video for 'Another Brick In The Wall' the other day and it has this older teacher dude rapping a young kid's knuckles for daring to write poetry. This sort of patriarchal oppression. It was very quaint. And nothing to do with the school system of today. So one of the fun things I'm playing with is just showing what that modern experience is. I'm not really trying to say anything important but I have no problems poking fun.

Nrama: Oliver's a very creative kid who channels a lot of that creativity into his drawings. Is this character autobiographical at all?

Andrews: How boring would that be! No one wants to read a comic about me. It would be horrible. Just full of loathing and self-hatred, combined with bursts of narcism and mania. No. No one wants to read that book.

But here's the dirty secret of comic book readers. They're all creative. And they all love to draw. Even if they're shy about sharing. The act of artmaking is actually embedded in the reading experience of comics themselves. And I think we are seeing a renaissance in artmaking for everyone, including kids. Just take a peek at the art tutorial videos on YouTube. Some of the most popular channels ever. I've always said this - but every comics reader is a creative person. Think of it more as a little wink to the reader.

But also, for Oliver's character, there is a subversive element to artmaking and making him an artist. Why is that? I think it's because any type of creativity is a threat to those systems that attempt control. Those systems only worship replication. Retweets, Hearts, Forwards, Likes.

And they try to diminish and control your creative impulse by rating how much it is replicated on their platforms and by their systems. All regulated by an algorithm. Your creativity becomes their product. They pay you in false praise or algorithmically generated replication opportunities while they sell advertising space to some widget-maker, poking you to create more so they can sell more. It's all a lie.

Every true revolutionary is artistic. Beware the corporations or the media or any entity that tries to sell itself as a revolution. These are systems of replication, not creation. Creation lies within one person at a time. It lies within you. And the best dramatic personification of that creative process is the story of a teenager, because that transition into adulthood is you literally creating your life. And so, by its very nature, a teen is also a subversive person. And the greatest teen characters always challenge systems and control. The rebel, with or without a cause.

Nrama: Without spoiling anything, can you tell us about what problems Oliver will be facing? Is there an E-Ratic rogues gallery on the horizon?

Andrews: The greatest fear Oliver has is someone finding out what he can do. It threatens not just himself but his family, his new friends, and the girl he falls in love with. He has to deal with his out-of-work single mother, his popular jock-type older brother, and a principal that is set on revenge against those he blames for his lot in life.

Nrama: This being a Kaare Andrews book, it's obviously packed with action scenes. Can you talk a little bit about how you draw those scenes? What does your process look like?

Andrews: You know... I'm not sure I would call this a 'Kaare Andrews' book. In many ways, it's not at all what you might expect. It's probably even very different. I'm trying things. Experimenting. Both with the art but as well with the storytelling.

I've found myself in a strange position in this industry, in that I can't help but do the other thing. Zig when others are zagging. So maybe I'm just in my own ocean, a fish that knows nothing of the water he's swimming in. But I find it very hard to identify what it is that I'm doing. I'm just doing it. And my process is to accept the situation.

With Renato Jones, I was really experimenting with layout as story. With Spider-Man: REIGN, I was experimenting with dualities in art and character. Iron Fist was about exploring metaphor and manifestation. But I never know what I'm doing until it's done. E-Ratic may just be a blip, a forgettable thing that's forgotten. But it may also be the pajamas your kid's wearing five years from now. It's all sort of beyond my control.

Nrama: You're working with colorist Brian Reber to bring E-Ratic to life; in your opinion, what does Brian bring to the book?

Andrews: Brian's great. I've known Brian forever but I think this may be the first time we've actually worked together. He's very collaborative and protective of the 'vision' of the book but also makes unique choices of his own.

I've been coloring my own stuff so much the past many years, it's nice to open it up and get some help. Brian makes me want to draw better. A little secret is that I've re-inked almost every page after getting it back because his coloring is such a palate cleanser. You can easily get lost in the process, but by handing the work off and getting it back again, you can really see all the little things you need to fix. It's been very helpful! I've really enjoyed sharing the character.

Nrama: Last question: you have an impressive resume outside of comics, with plenty of TV and film credits to your name. How has working in the film medium affected how you created E-Ratic? Or how you create comics in general?

Andrews: Film and TV are perhaps the medium of the moment. But it's no coincidence that the most successful films and shows of late have been comic book shows. And it's for this one reason: Film and TV come with a giant machine of many voices all trying to control success. And it can create a sort of gridlock. A logjam of everyone trying to influence the creation of a thing, without being the creators of that thing themselves. Imagine trying to invent a new cookie recipe with a kitchen full of 20 people with a financial interest in how good it tastes? The challenge of making art in the film world is navigating the fears and desires of those twenty people.

Comic books are created by teams of one to three people. But one person could do everything. It's the most direct medium of visual storytelling in the world. And it provides the unadulterated spark of life that a giant machine, like film or TV, needs to harvest, because by the nature of what that machine has become prevents that spark from ever happening. The whole process is corrupted by fear and good intentions. But real storytelling, real creation, happens in spite of fear. It risks failure. It challenges and provokes. All the things that committees and gaggles of executives are built to stomp out. Creativity is not a team sport. It is a singular process, manifested by individuals, who take the risk of failure willingly. And the more you put on the line, the greater potential that piece of art has to succeed. Or fail. You must seek the risk to ever find the reward. And because comics are so cheap to make, they can risk so much more.

In short, when I do a comic book, I'm all in. I put my directing life to the side.

Grant DeArmitt is a NYC-based writer and editor who regularly contributes bylines to Newsarama. Grant is a horror aficionado, writing about the genre for Nightmare on Film Street, and has written features, reviews, and interviews for the likes of PanelxPanel and Monkeys Fighting Robots. Grant says he probably isn't a werewolf… but you can never be too careful.