High seas steampunk meets avian action in The Falconeer, a gorgeous aerial shooter about "dealing with your past"

How a troubled developer found a future in the sky

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. If you want more great long-form games journalism like this every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

Around five years ago, Tomas Sala experienced a period of terrible burnout, brought on not just by overwork but the stress of being part of a team. "I realised that I'm shit at working in groups, and I'm not a good leader," he says. "I'm always the guy who does feature creep, who can't get the focus. That led to a lot of conflict." Some of Sala's turmoil found expression in a "very dark" solo project, developed during his recovery. But as he put his life back together, finding new love and becoming a father, the darkness gave way to something hopeful – the image of a bird, swooping and plunging across the water.

"It represented a much lighter stage of my life," Sala goes on. "But it's also about dealing with your past." Birds are symbols of aspiration, Sala notes, but in order to really resonate, that symbol can't be fully separated from what it's trying to escape. "It's always that interplay." Sala eventually abandoned the game of darkness in favour of one that lives this interplay between bird and darkness, the joy of release and the memory of pain.

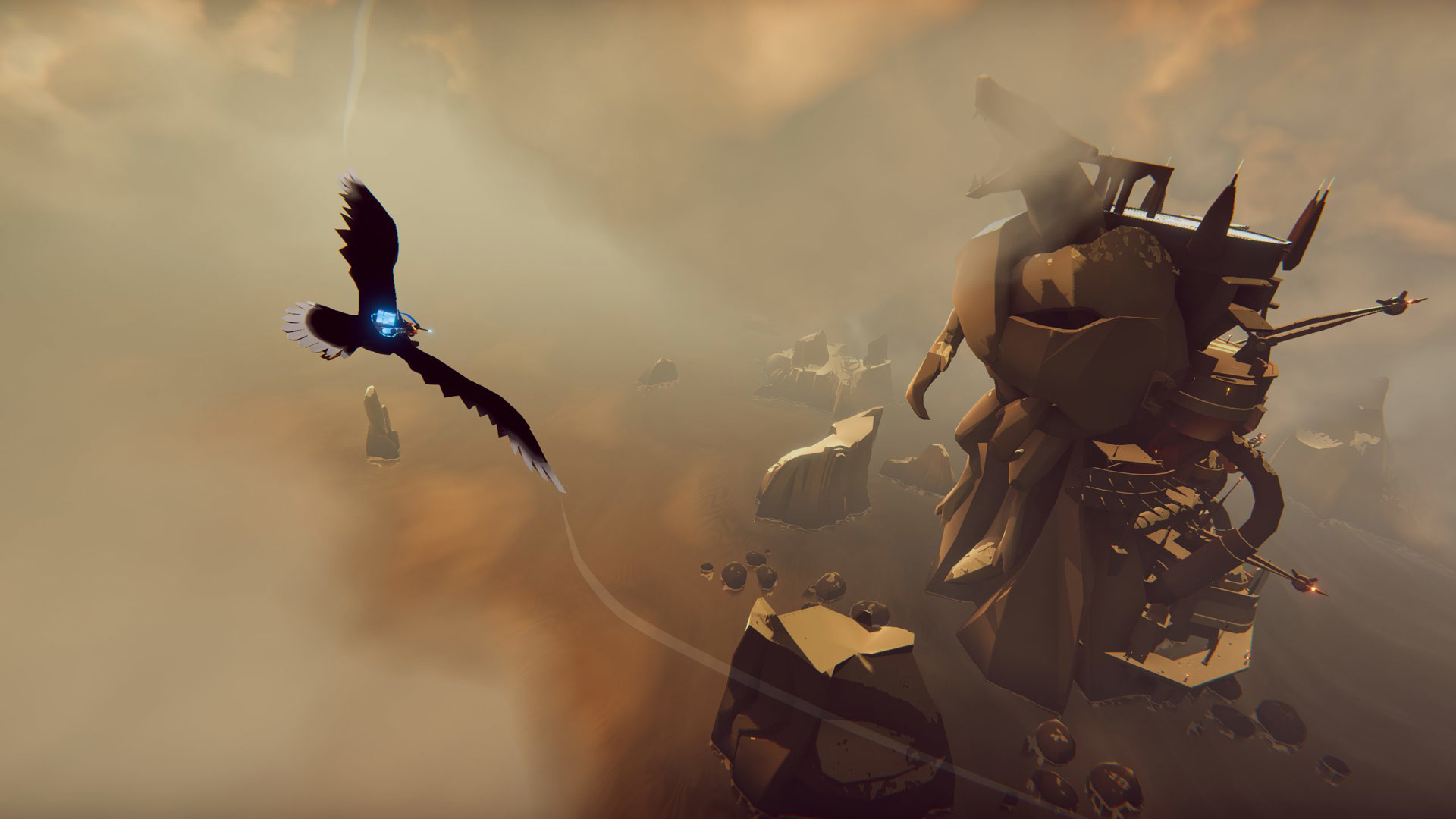

The Falconeer is a work of deceptive levity. Primarily, it's an open-world air-combat game in the spirit of Crimson Skies – a blend of World War dogfighting and briny steampunk, in which ace pilots do battle aboard giant falcons, hurling fireballs and lightning. But it's also a work of introspection, comparable to Jo-Mei's Sea Of Solitude – a game that seeks answers and catharsis in the depths. "Even though you're in the air, being lofty, elegant or combative, all the secrets, all the things you really need to confront, are always below the ocean," Sala says. "They're tied to the deep."

Life at sea

The game's ocean itself speaks to this duality. It's a heaving grey monster, at first glance, sucking at the edges of cramped island towns and fortresses. But it also teems with activity. Bottle-sized, gold-trimmed sailboats trundle from port to port. Leviathans burst from the waves, tempting you to fly beneath them. Airships push through knotted cloud. The world's mood and texture are continually changing, as day gives way to night and duelling falconeers are swallowed up by storms (which serve as a risky but convenient energy source for your weapons). If this ocean harbours bleak truths, it is also a place of wonder and adventure – to say nothing of ancient relics and bubbling conspiracy.

The Falconeer's story is broken up into five memories, one for each faction vying for possession of the ocean and its trove of submerged, long-forgotten technologies. Presided over by a mysterious shaman narrator, they form a tale that ultimately deals with the origin of this world. Each faction has its home ports and story objectives within the grander narrative. Ports are where you'll buy ammo such as armour-piercing lightning rounds – stored in neon canisters on your mount's back – and take on missions that range from bounty hunts through racing and fishing to escort missions and area defence.

The settlements themselves are lovingly wrought, lent personality by snowglobe flourishes such as market stalls and lines of drying clothes. "I like to make worlds, and then the worlds need to be inhabited and correct," Sala says. "That's super-soothing for me." He compares the making of these ports to kit-bashing, the art of cobbling together pieces from different miniatures, but admits he has no taste for physical model-making. "I have ADD, so I'm a fidgety person – I'll break everything, and then you have to wait for the glue to dry. But I love watching model makers on YouTube, and it's very much the same process." The feeling of delving into a box of models is amplified by The Falconeer's clean art direction, which emphasises proportions over intricate surfaces. "It's not really 'low poly', but I don't use any textures – the snow and all the noise you can see, that's Perlin noise. Everything is [made up of] shaders with sine waves and geometry."

"Even though you're in the air [...] all the things you really need to confront are always below the ocean."

Tomas Sala

The Falconeer's air combat feels as graceful as its art direction. Steering your bird in third person, you stoop to fill up an energy bar that is drained by gaining height, boosting and performing evasive rolls. A lock-on lets you pinpoint individual pieces on larger targets, whether to sabotage a dirigible's engines or set off a chain explosion by destroying a turret.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

These skirmishes are most gripping when they border on overwhelming, with projectiles crowding the screen and AI wingmen yelling at you for instructions. Classic arcade sims such as Wing Commander aside, Sala has taken copious inspiration from vintage war movies. Some islands are decked with barrage balloons, plucked from the beaches of Saving Private Ryan to deter the would-be Stuka. Other defences can be turned against their owners – sea mines, for example, can be scooped up and hurled at clifftop artillery, providing they don't explode in your talons.

Each faction is crisply defined by its ships, costumes (there are animated character portraits redolent of Star Fox) and architectural style. There's an imperial faction modelled on the British and Napoleonic empires of the 19th century, all bristling ironclads and gleaming brass. "I might have seen too much Adam Ant when I was younger," Sala notes of their outfits. Perhaps the strangest faction is a group of exiles who ride flying seabeasts, strapping cockpits to the spines of eels and manta rays: even their ports are constructed atop giant crabs. The most sinister are the Mancers, a high-tech monastic order comparable to the Brotherhood Of Steel in Fallout.

Eye in the sky

"They're kind of nerdy, but they've got their marketing down, so they look really badass," Sala comments. "They fly on dragons and they have more exotic ships." The Mancers are the Ursee's Machiavellians, playing all sides against each other, bestowing choice gadgets on those who carry out their designs. "They're not interested in running the place, but they are steering it towards a certain goal."

The Mancers are the creators of the Maw, a watery canyon running the length of the Ursee, as though left that way by an absent-minded Moses. It's one of many nods in The Falconeer to the Bas-Lag novels of China Miéville (in this case, his eerie nautical epic The Scar). "I love his worlds, because they're very believable, but there's lots of mystery and it's always really weird."

There's at least one piece of Sala's previous, abandoned game to find in The Falconeer's ocean – the statue of an animal resembling a weasel, crushed by what looks like an enormous, gnarled fist. It's an important memento for Sala, a reminder both of the suffering he felt and how far he's come since. Today, he looks back on that difficult time with equanimity and perhaps a certain thankfulness. "[In a way] it's been the best thing in my life because it allowed me to do this – to do something new."

Check out the big new games of 2020 on the way this year, or watch the video below for a guide to GamesRadar's favourite games of the past decade.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.