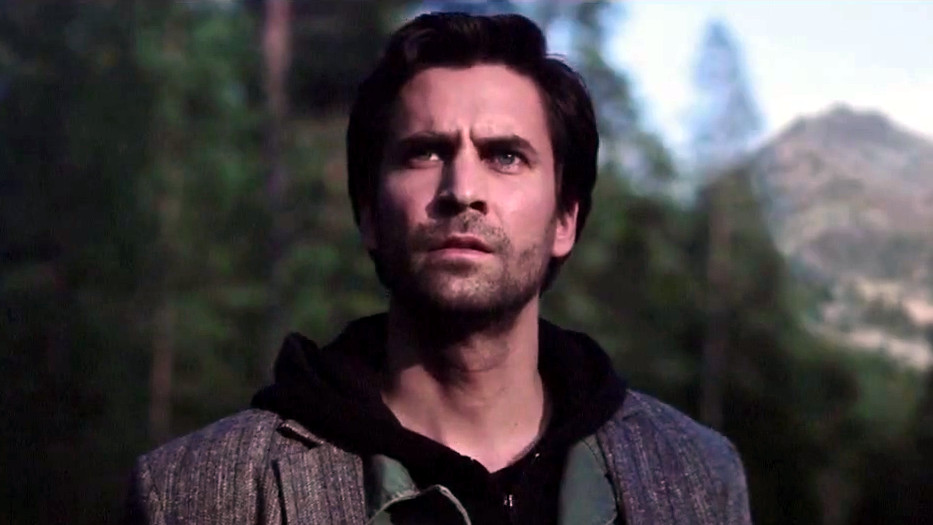

Alan Wake was almost an open-world Silent Hill, here's how it evolved into something else entirely

The untold evolution of Remedy's big budget thriller from the people that were there at the time

Before it finally arrived back in 2010, Alan Wake - one of the hottest, most anticipated Xbox 360 games - had drift into myth territory. Since its unveiling in 2005 many other massive 360 exclusives graced the console - Gears of Wars came and went, Halos came and went, Project Gothams came and went, and Alan Wake stayed… silent. Until, ultimately, many believed the psychological horror was just vaporware and empty promises. However, over in Finland, Remedy’s ambitious project was just starting to come together – and it was changing all the time. Alan Wake was completely removed from Steam recently, making it unavailable to buy on anything but disc, and that kickstarted a renewed interest in the game. If you're one of many people who picked it up, read on for the fascinating story of its creation...

In Remedy’s eyes, the only myth concerned with Alan Wake was talk about delays and inordinate development times. As writer Mikko Rautalahti explains, Remedy Entertainment wasn’t a studio equipped to churn out titles year after year. “It sounds like a really long development time when you look at the years but that’s not really a great way to measure the amount of work involved. It really comes down to man hours. We’re a very small development studio by modern standards. There are studios that put out a game every two years, but they typically have at least two or three times as many people on staff as we do.”

Remedy isn’t just any old small outfit - it’s one that created its own tech. “When we revealed Alan Wake in 2005,” begins art director Saku Lehtinen, “it was clearly in the preproduction phase and the technology was very much in the works. We continued refining everything around 2006-2008, and during this time we also explored and changed many fundamentals of the game. After taking out the time spent on preproduction and tools development, the actual game’s production time was not that exceptional in terms of overall time: a bit over two years.”

Although Remedy stresses the project didn’t overrun its planned production window, there’s one factor which undoubtedly contributed to a chunk of that time: the abandoned sandbox roots. For years we all believed Alan Wake was a cross between Silent Hill and Grand Theft Auto, but in reality the open world was dropped long ago.

“It really came down to the storytelling,” says Rautalahti, dispelling any thoughts of technology troubles. “We make story-driven action games here at Remedy. And yeah, at one point, it was also supposed to be an open world game, with the free roaming, sandbox, and whatever other buzzwords you would care to throw in. That was certainly the trend at the time, and we began experimenting with it.

“Unfortunately, it just didn’t work for us. From a narrative point of view, it’s a very, very challenging game type, especially for a thriller. If you look at what we do in Alan Wake with the environment, the atmosphere and the music, try to imagine that in an open world setting – let’s say you’re going to that meeting with the bad guy at Lovers’ Peak. The soundtrack fires up, the fog starts to roll across the hills, there’s something rustling in the undergrowth. But then the player decides that what he really wants to do right now is some logging missions. So what do we do? Do we stop building the atmosphere and reset the environment? I mean, we can do that. It’s not difficult from a technical standpoint, but the atmosphere just isn’t gonna survive that. We learned that the hard way.”

Even though you never have the opportunity to explore it freely, the open world still exists in the background. “We still have a continuous area of about 10x10 kilometers that is outlined to various levels of detail and follows the original philosophy of a condensed Pacific Northwest experience,” confesses Lehtinen.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

“If it ever puts the story integrity into jeopardy, I do not see us doing the open world quite the way that people are accustomed to. However, creating smaller sandbox-styled sections in our own way to designated areas that stay within the boundaries of the story is not off the table.”

What could have been?

The sandbox world wasn’t the only feature that didn’t make it onto the retail disc. Every scene and element in Alan Wake needed to justify the time investment in order to make it happen – a practice no different from production in any other title – and as you’d expect, not everything made it. Bickering Sheriff Deputies Mulligan and Thornton – two team favorites – suffered that fate, although echoes of their existence live on in the police radio transmissions. “We like those guys, we’d really like to do more with them sometime,” Rautalahti says.

An entire dream sequence was chopped from Alan’s missing time in the trailer park as well. “Wake went from one disturbing scene to another, typically seeing and hearing things that stemmed from his own insecurities and fears – he saw Sheriff Breaker and Agent Nightingale plotting against him, and both Doc and Dr. Hartman diagnosing him as an insomniac alcoholic who exists in a state of perpetual denial and delusions. It was a very fun sequence, but it was also a lot of work, and it wasn’t doing our pacing any favors.”

The best chapter left on the cutting room floor originally lived just before the trailer park. “We had a tour of the gameworld - a seaplane ride where we went to another location on the coast to do some investigating. The seaplane had a very chatty pilot who talked about local events and locations, constantly interrupting Barry as he was trying to talk about the stuff he’d uncovered. Once they landed, there was supposed to be a sudden storm, and the whole thing culminated with this desperate run to the lighthouse.” Sadly it felt like too much of a detour from the main story and so suffered the same fate as the dream sequence.

As Special Edition owners who have played through Alan Wake with the commentary switched on will know, more scenes came close to the snip. Both the trailer park and New York apartment were candidates for the scrapheap. “As far as the New York scenes go, that wasn’t really a question of whether they got axed, it was more a question of whether they got made at all. A lot of time and effort went into creating the New York apartment. There was a lot of justified concern about putting work into what’s essentially a couple of very short scenes,” reveals Rautalahti. “The trailer park was far closer to being cut,” adds Lehitnen, “as it was pretty difficult to script reliably and we kept getting poor feedback from play test results for quite some time.”

Remedy’s concerns proved to ultimately be all for nothing. Both the apartment and trailer park areas functioned as welcome breaks from the intense forest exploration. The negative feedback forced Remedy to look at the playtesting method itself. Playtesters were being asked to trial individual sequences at a time, so Rautalahti deduced it wasn’t surprising to discover the more sedate areas were getting less enthusiastic responses.

“If the only thing you play about episode two is the Sheriff’s station sequence, you’re probably going to think that it’s not very exciting; it’s just people talking. But when you see it in the intended context, as a build-up for the things that happen in Elderwood after that, it’s a whole different thing. Suddenly, it becomes an episode with a nice degree of variety. It was a great example of how much context and pacing matter.”

One of Rautalahti’s most surprising revelations is how the team originally prioritized daylight sections over night. In those days the Taken weren’t just confined to the shadows. “At one point the light worked only as a multiplier. The light didn’t really do anything to the Taken by itself, but you could do more with a little gun in the light than with a hunting rifle in the dark.” But the enemy types didn’t work during the day. “Our enemy concept was very much the I Know What You Did Last Summer-styled man: a dark avenger, whose eyes and thoughts are obscured.”

Remedy experimented with armed Taken but the guns didn’t sit well with the team. “We did not want distant shootouts where the player would try to snipe the enemies from (afar). Enemies had to be able to get on your skin.” The possessed items, however, had a very different origins story: they were birthed from a simple physics issue. One buggy, jittery object was enough to sell the idea of poltergeists to the team, and so Alan’s second major foe was born.

Reawakening Alan for a sequel?

If Remedy was to have a second chance at Alan Wake’s development, Rautalahti is totally clear as to what he’d do differently. “Well, I would never, ever mention the words ‘open world’ in public, for one thing. We have had to work very hard to try to dispel that image during the past year – that’s just a very difficult thing to do. “And there’s always going to be stuff that you didn’t have the time or the resources to work on. The manuscript pages are a great collectible, because they really are an integral part of our story. I wish we could’ve done something comparable with the thermoses.”

The thermoses are an interesting collectible. They were always designed to be basic collectibles, but during the early days they could have filled another role. “Rather than thermoses per se, coffee was actually suggested to be one candidate for a source of player health, if we ever needed one,” admits Lehtinen.

Any regrets will likely remain with the developers, sadly. Alan Wake 2 was definitely on the studio's mind back in 2010, but it shows no sign of ever being created. “There will be more Alan Wake, if we have anything to say about it,” muses Rautalahto, back in 2010. “It’s a bigger story than just one game, and we want to make it very weird and scary and wonderful. I’d like to say that if our offices were wiped off the face of the Earth and all you ever got was that first game it would work just fine as a standalone product. I know some people don’t see it that way, and I don’t necessarily blame them for that, but it’s not intended as a huge cliffhanger, it’s an ending to that story. Obviously, we also set things up for what’s to come, but it’s definitely an ending. It’s not a situation where the bomb is about to explode and you don’t know if they’re gonna make it, or something. We have a very definite story arc and the weird and horrible things that happen to him, and what he needs to do in the end to put things right. Then he needs to do something else. We’ll get to that when the time comes.”

Will the time for more Alan Wake ever come? Seven years after the original release, and one Steam removal later it seems... unlikely. But stranger things have happened, and long dormant franchises like this rarely sleep forever.