Modern Warfare's Death From Above mission is still the model for quiet unease in Call of Duty

Modern Warfare is focused on realism, but there’s still plenty it can learn from Call of Duty 4's most harrowing mission

Call of Duty is known for its bombast – despite the expensively produced scores, its most recognisable soundtrack is a cacophony of machine guns. Yet one of the most memorable missions in the series' long history is distinguished by its eerie quiet.

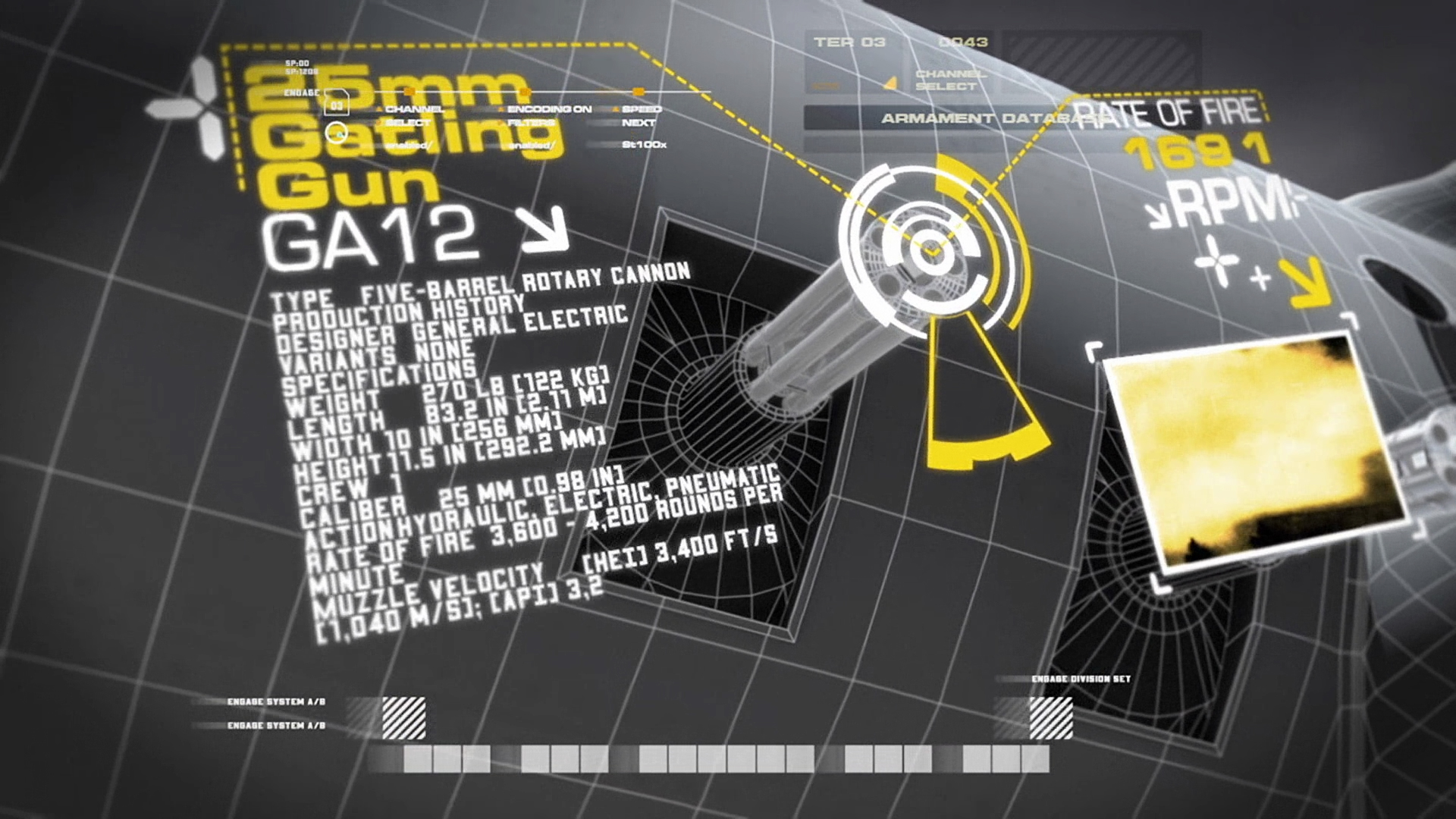

Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare’s eighth mission, Death From Above, casts you as the gunner in an AC-130 Spectre, a US aircraft designed for close air support at night. The scene opens with a fetishistic accounting of your firepower, as if a pre-awakening Tony Stark were demonstrating the military might of a new superweapon. The camera swoops around a 3D render of the aircraft, slowing to circle the cannons that hang phallically from the ship’s exterior; 83.2 inches long, ten inches wide, 4,200 rounds per minute. It's a gratuitous display typical of shooters of the time, and particularly those out of Infinity Ward, a studio whose admiration for soldiers and their equipment was clear. But what follows, in this case, makes you afraid to fire those weapons at all.

Call of Duty has always played with perspective. Originally it was a conceit that simply allowed you to see the breadth of the European Theatre of World War 2, through the eyes of a US paratrooper, an SAS saboteur, and a Russian volunteer raising the victory banner over the Reichstag. By the time Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare released in 2007, however, Infinity Ward was using perspective for highly specific emotional goals. One of the game’s first scenes traps you inside the body of a deposed president as you are flung into the back of a car, snarled at by your captors and driven to your execution, robbed completely of control.

In the build-up to Death From Above, you've been John MacTavish, member of an SAS squad shot down over western Russia while exfiltrating an informant. These are men you’ve seen close-up by now, and know by their schoolyard names: Soap, Price, and Gaz. Now, suddenly, they’re reduced to white specks on your thermal imaging equipment. Friendlies are tagged with flares that see them sparkle like ocean waves in the sun, but beyond that there’s little to distinguish them from the ultranationalists swarming on their position. It’s disconcerting to know that you are down there – and to not be absolutely sure which of the white dots is named Soap MacTavish.

Emotional disconnect

While you're personally connected to the people on the ground, everything else about the mission conspires to disconnect you from it. Have you ever got back home so late that familiar shapes become hard to recognise, recast in the artificial half-light of street lamps? There's something of that in the thermal cam of the AC-130. "You are not authorised to level the church," warns your navigator. But which one's the church? While preferable to pitch darkness, the black and white glow is difficult to read, like an x-ray.

The distance in itself is dehumanising – not only because you're spared the blood dispersed by your explosions below, but the screams too. You hear the clack of your cannons firing, but not the boom when they hit, removing you from the consequences. Instead, the entire mission is accompanied by the malevolent bass note of your plane’s engine – a flat drone unmoved by the chaos on-screen.

Your only feedback comes from your fellow crew. "Woah," yells the TV operator after a direct hit. "Hot damn!" Occasionally, the fire control officer chuckles in approval. "Nice. Good kill. I see lots of little pieces down there."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Watching together through the screens, they come across like a twisted Gogglebox family, commenting on the unfolding mission as if it’s post-watershed entertainment. At one stage, Price and his squad commandeer a civilian vehicle on the highway to aid their escape. "I bet that guy’s pissed, that’s a nice truck," says the TV operator. "Nah," replies the FCO with a laugh. "He's scared shitless."

Caught in conflict

At the mission's midpoint, there's a lot of back and forth as the crew attempt to find the right village to bomb, exchanging details about the curvature of roads and the identifying features of buildings. Is it the u-shaped one we need to demolish, killing everyone inside? Today, the sequence is unsettlingly reminiscent of the report from an accidental US bombing – one that killed 42 people in a Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan.

As a real-life AC-130 crew attempt to clarify whether or not the target in their sights is, in fact, a Taliban command centre, the transcript devolves into a very familiar and human case of workplace miscommunication, with terrible consequences. "I feel like – let's get on the same page for what target of opportunity means to you, and what target of opportunity means to me," says a confused navigator. "I mean, when I'm hearing target of opportunity like that, I'm thinking [REDACTED] – you're going out, you find bad things and you shoot them," replies the FCO.

It’s this same lack of clarity, with life-or-death results, that makes Death From Above such a frightening and potent mission more than a decade on. It's emblematic of Modern Warfare's power in playing with perspectives, putting you in a position where you can actually kill one of your protagonists if you’re not careful.

The new Infinity Ward in charge of the Modern Warfare reboot has expressed an interest in dialling back the spectacle – rewinding all the nukes and invasions of the original trilogy so that Call of Duty can land close to home again. The developer could do worse than look to the muted unease of Death From Above, a disturbing unreality that captures the ambiguity at the heart of contemporary conflict.

Learn why Gunfight is a challenging celebration of the changes coming to Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, in our hands-on preview of the upcoming multiplayer mode.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.