How Star Wars made (and then ruined) modern Hollywood

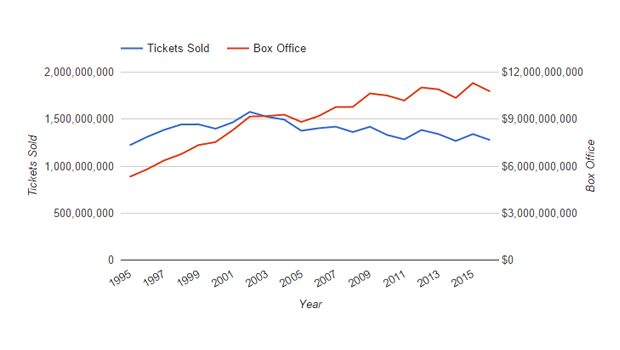

Mainstream Hollywood cinema is bigger, brighter, and brasher than it has ever been. Its films are more hyped, more merchandised, and more generally everywhere than ever before. Movies are the lifeblood of message boards, social media posts, web traffic, and every other piece of populist media that can possibly cover them. But ticket sales continue to drop.

It shouldn’t be happening, but it is. Hollywood is making more money than it used to, but if it weren’t for inflation, it might be making a fair bit less. The simple fact is that for all of the increasing spectacle on screens, and all of the additional outlets for hype and persuasion, fewer people are going to the cinema.

Hollywood has never tried harder, or invested more, into whipping us up into a screaming, money-throwing fervour. But it isn’t working. Why is that?

I think the answer is that Hollywood’s methods of fervour-thrashing have gone rather wrong. Because mainstream Hollywood, rather than evolving, diversifying, and embracing all of the advantages of the modern world in order to deliver better, more progressive, more exciting content to the increasingly savvy audiences who crave it, has bunkered down in the past and started treating its audience like eager, all-consuming simpletons.

It’s easy to lay the blame for this apathy at modern Hollywood’s penchant for sequels, remakes, and ‘safe’ bets, but it’s not as simple as that. The current status quo is indeed creatively problematic, but it hasn’t just appeared out of nowhere. What we’re looking at now is the product of decades of slow drip modifications to Hollywood’s behaviour: some understandable, some knee-jerk, all of which have led to the same big, homogenous puddle of cinema we see now.

And it all started with Star Wars.

Before Star Wars, there wasn’t really any such thing as the blockbuster we know today. There were big, successful films that eventually led to sequels, but the kind of multimedia, merchandise-spewing, books, toys and games spawn-point of a movie didn’t really exist. But then Star Wars created it. Famously, creator George Lucas took a reduced fee for directing in exchange for a big cut of the merchandise rights. And ye gods did that pay off. Star Wars toy sales went through the roof, and continue to do so. And, with A New Hope planned as the start of a trilogy, built-in sequels - and thus Star Wars’ exponential growth as a brand as well as a movie - were guaranteed upon its success. Suddenly the blockbuster franchise had been born, and Hollywood’s money men would never think the same way about films again.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

For a while, the effect wasn’t entirely noticeable. Big films still happened, some of them got sequels, and a lot of them got merchandise, but the momentum was fairly sedate and sensible. Ghostbusters was huge, but there was a five year gap before Ghostbusters 2. Alien didn’t get its first sequel for seven years, and it was another six before Alien 3 turned up. But the seed of the pre-built mega-ton franchise had been planted, and eventually it started to germinate, watered with financial temptation.

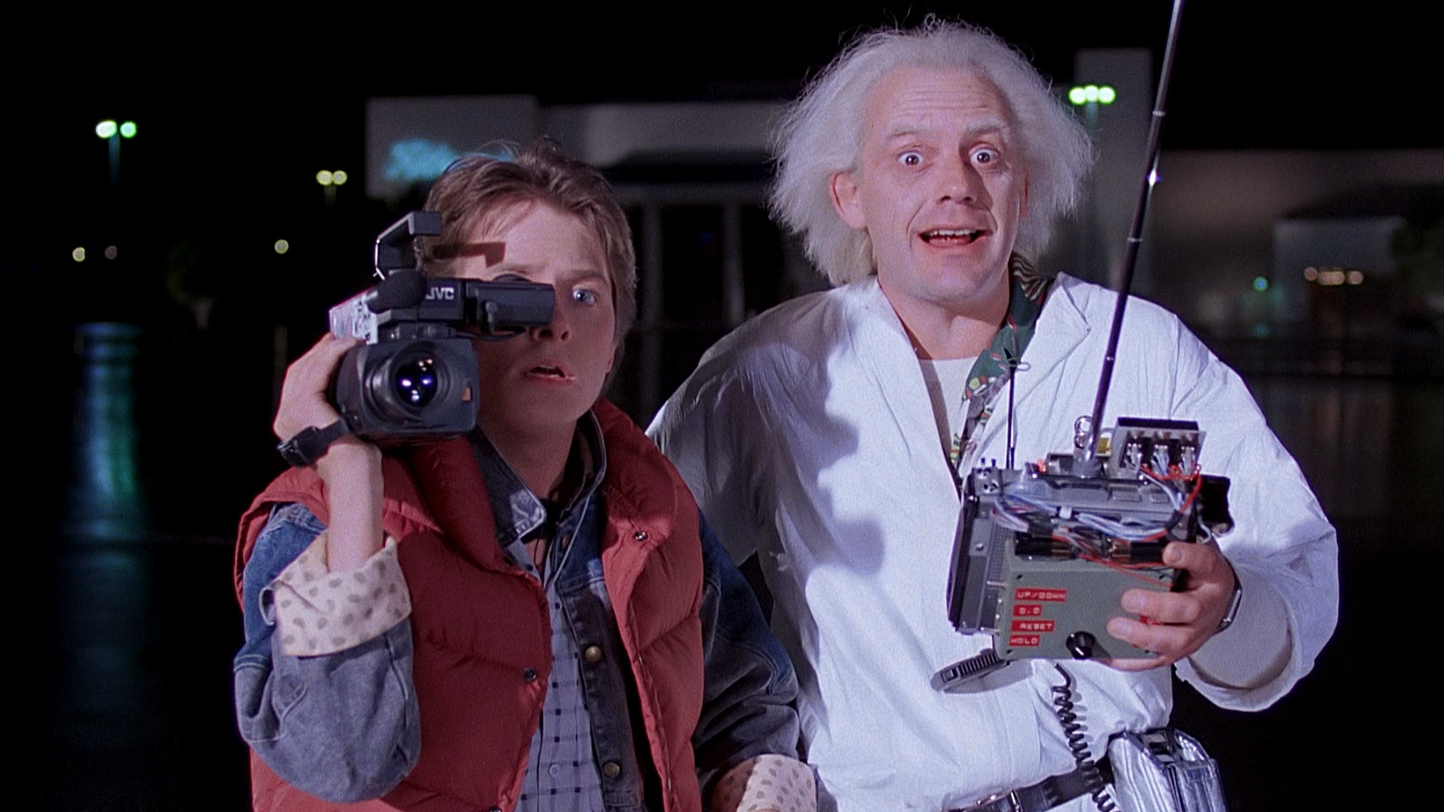

Possibly the first big pre-fabricated trilogy, post-Star Wars, was Back to the Future. The first film ended on a cliffhanger, and then when Back to the Future: Part 2 was made, it was shot back-to-back with its own sequel. There are various stories as to why this happened. A prominent (and plausible) one is that the studio wanted to get the trilogy finished before Michael J. Fox got too old to play a teenager in a series that, in-movie, plays out only over a matter of weeks. But the idea of creating another big, monolithic event out of a rapidly released, three-movie arc, cannot have been far away. Either way, Back to the Future further normalised the process, and it was only going to accelerate from this point on.

Sequels steadily became assumed, rather than simply a possible side-effect of a successful film. And as sequel-scope added all that tempting extra money to the greenlighting of any particular film, so Hollywood seemed to start to look beyond even the potential of ticket sales. It remembered Star Wars. It remembered that attaching merchandise to these franchises could blow up the earnings even higher. And then, subtly, films began to change.

Over a period of time, sequels to successful blockbusters began to soften. Their tone began to shift. They began to get lighter, and more kid-friendly, because if the kids could watch the films, the kids could buy the toys. Look at Robocop, which moved from hard-hitting, brutally gory satire to goofy action with flying cyborg ninjas, and a TV series, and a cartoon. Look at Batman, which changed its ethos from dark, freakish, art deco gothic cape pathos to camp, day-glow, nudge-wink silliness. Look at the damn Terminator, which devolved from tense, violent, R-rated sci-fi mood-piece to a PG-13 kids’ action movie that felt for all the world like a pilot for its own tea-time TV series.

The nature of franchises had changed. Where once, Back to the Future was built as it was in order to successfully finish a series, now the franchise model was being used to create things that hopefully wouldn’t end. And whose tone and initially successful values could be switched out on the spot in order to amplify their income. As a result, as much by accident as by design, franchise names began to exist only as recognisable labels with which to entice audiences with familiarity, rather than actually, necessarily, standing for anything that they used to represent. They often entirely forgot the creative essence that made these properties successful in the first place. Look at the two Alien vs. Predator movies. The coming together of two utterly iconic, tonally distinct works, that fail to evoke what’s important about either.

It was an important turning point, because it made the franchises that audiences used to value inherently less valuable, and it started to seed cynicism and distrust about sequels and top-line Hollywood products. The follow-up to anything you’d liked could easily turn out to be a dumbed-down disappointment, with the condescending assumption that you’d like it anyway.

But it didn’t happen in isolation. It coincided, give or take a few years, with an external threat to Hollywood that would totally throw off its thinking. The internet became a mainstream part of life and, therefore, entertainment, and Hollywood didn’t know how to handle it at all.

Forget big studio arguments that piracy started to kill the film industry. That’s a whole other discussion – and incidentally, it didn’t. High profile movie leaks are clearly on the increase, frequently from inside the studios themselves, but it doesn’t seem to be harming the films in question to any significant degree. What happened, what was really important, is that the audience culture began to change exponentially. At the same time as ‘franchise’ came to represent as much tired pessimism as excitable, fannish enthusiasm, the motivated film-lover found that they no longer had to simply accept what Hollywood was offering.

Suddenly, niche films could become well-known by digital word of mouth. Unknown directors could be championed and celebrated by fan-bases that might previously have had trouble hearing about them at all. Anyone looking for ‘their sort of film’ to watch could find ten new ones a day, far and wide from the mainstream multiplex feed. Online ordering of increasingly prolific DVD home releases, and – later – entirely online distribution also made accessing this stuff far less of a hassle, and often much cheaper, than trekking out to the cinema to see whatever unreliable fare the big studios were deigning to create.

In fact, online word of mouth became so powerful that it could be more than an avenue for mildly amplifying the fortunes of the obscure. It could be a genuine king-maker, either at the cinema or during the later, home-releases of over-looked movies. Look at Dredd. Look at the original Blair Witch Project. Hell, look at The Matrix. The Wachowskis’ cyberpunk masterpiece was always going to do well, but hype exploded online - because hey, turns out late ‘90s internet users really liked smart cyberpunk. Though of course Warner Bros. responded with hastily churned-out, desperately poor production-line sequels of increased, but vacuous, spectacle, immediately spurning the good-will and turning the series into yet another, instantly burned-out franchise. It missed why the first film was a hit, planned in terms of why it thought it was a hit, and patronised another savvy, eager audience into alienation.

And it wasn’t just film that was changing. Long the poor relation - due to lower budgets, equally heavy commercial obligations spiralling from an ads-driven business model, and an even more rampant propensity to run every idea into the ground - around the mid-to-late ‘00s, TV started getting good. The trigger for this most violent and spine-rattling of see-saw swings came in the form of three letters: HBO. Building a groundbreaking reputation for high-quality, writing-driven, cinema-quality TV from the late-’90s onward, the paid-for cable channel, free from traditional, mainstream concerns due to its lack of need to pander to advertisers, has influenced the state and standard of modern TV more than any other factor in the last couple of decades.

Oz. The Sopranos. Band of Brothers. The Wire. Girls. True Detective. Sex and the City. Game of Thrones. As a result of HBO’s efforts, genuinely adult - in all senses of the word - high production value, well-crafted material became to be standard on TV. And with audiences naturalised to this new wave of ‘serious’ television, other channels followed suit, this kind of programming now no longer risky, but commercially important. Breaking Bad. The Walking Dead. Mad Men. And then online services got involved. Hello Netflix, and your spiralling array of Originals. Hello Stranger Things. Hello House of Cards. Hello Jessica Jones. Film was no longer safe in its status as the home of serious, high-budget entertainment. TV was producing better-than-movie-quality content, and discerning viewers had hundreds of hours of it a year, that they could often watch from the comfort of their own homes, whenever they wanted. The impetus to go out was not going to get any stronger.

And this made Hollywood panic. Rather than being progressive and pro-active in regard to the way that new, more interesting, more engaging material was discovered and consumed, it became reactive and defensive. Instead of looking for new avenues and new opportunities, it doubled down on what had worked before. It freaked out about the competition, but primarily it freaked out about the mechanisms of the competition, not the fact that intelligent audiences were being courted by better entertainment. For evidence of this mentality, just look at this year’s CinemaCon, where seemingly most attendees virulently fought the idea of Screening Room, a proposed new, at-home viewing system for cinema releases. Only JJ Abrams defended the initiative, explaining:

“Much has been said of technologies that threaten the theater experience. I'm open to all good ideas. We need to do everything we can in this age of piracy, digital technology, and disruption to be thoughtful partners in the evolution of this medium. We have to adapt. We need to meet that challenge with excitement, and create solutions, not fear.”

Everyone else? The general vibe seems to have been one of mild trench warfare, the weapons of choice being, yes, another barrage of reboots and sequels.

So Hollywood remained readily focused on franchises, rebooting, remaking, and resurrecting old ones at the same time as flogging new ones as quickly as possible. Hello, five Transformers films in ten years. Hello, two miserable, point-missing Die Hard sequels no-one wanted, related to the original trilogy only in name and lead actor. It went looking for more recognisable IP to buy up, ideally that which was superficially similar to films that had done well previously. Hello, every flailing Young Adult fantasy novel series in the wake of Harry Potter, of which there are now almost as many as actual Harry Potter films. The Hunger Games is the notable aberration, but that spawned a whole wave of lesser teen dystopian stories in its own right.

Hollywood went looking for franchises to lock in for multiple, pre-hyped sequels before the first film was even made. Hello Avatar. Hello, too many Hobbit films. It concentrated on bigger spectacle and gimmicks (hello, 3D) to try to drag people back into the cinema. It made films bigger and more expensive, not necessarily more interesting. It completely missed the point that audiences had more knowledge and more options, and continued treating them like the same, less informed audiences of yesteryear, assuming they simply wanted bigger, shinier things. Because after so long in its bubble, after resisting the internet, and the eclectic new world of the more educated, more engaged film-fan, Hollywood seemed to know only how to trade in bigger, shinier things.

Not only that, but it seemed to have lost track of the place of cinema-going as a social experience. When it was the only way to consume films, it was a bigger deal to more of the populace. A ‘big night out’ event. It was no longer that, not with so many other options available. Not with the traditionally lucrative teens and early 20s market now able to socialise online in a whole bunch of different ways, often while actually watching films at the same time.

It was a self-reflexive, self-fulfilling spiral. Remakes and sequels might have made money – amid noticeable misfires, flops, and bad PR – but it didn’t do anything so solve the problem. It was like wedging more and more tissue paper over a crack in the Hoover dam, while throwing increasingly large buckets of water into the top reservoir. Bigger, more visually chaotic films might have grabbed more attention, but they did nothing to give the more discerning film fan something meaty to reignite their excitement. The sort of viewers who would be enticed by these tactics were only, well, the sort of people who would be enticed by these tactics. The more casual viewer. The one that Hollywood didn’t really need to get back. The more selective, passionate potential audience members were still staying away more than they wanted to, because Hollywood still wasn’t providing enough for them.

The obsession with safe-bet similarity went even further, eventually reaching ludicrous degrees. Notice how many comedy films from the 2000s have almost exactly the same, red-and-white poster style, in order to subliminally remind potential viewers of another comedy – any other comedy – they might have enjoyed? Notice how many increasingly specific genre-parody films cropped up in the wake of Scary Movie and its endless black hole of sequels? Epic Movie. Superhero Movie. Date Movie. Not Another Teen Movie. Paranormal Movie. Despite their rubber-stamp titles, many of these are actually entirely unrelated productions. And their advent is particularly damning. Not only had Hollywood consolidated its output into increasingly formulaic productions of ever more sterile homogeneity, it had begun to use the very generic conventions it had created as fuel for (admittedly almost satire-free) self-parody.

It had created a self-cannibalising spiral leading down to precisely nowhere. A swirling plug-hole of blurring, merging content, with no final destination. Hollywood had become a snake eating its own tail, then sicking up the tail bits, and eating them all over again.

Hollywood followed its continuing tales of falling ticket sales not with a drastic re-look at the kind of output it was producing, and how it was distributing it, but by again blaming piracy, and then jacking up the prices of film prints in order to make a bigger profit while adding quite literally nothing.

Cinemas had to raise ticket prices and the cost of food and drinks in order to stay afloat.

And so, all audiences became less enthused about the idea of going to the cinema at all.

So what’s the endgame here? Is mainstream cinema doomed to circle fruitlessly in a bowl made of its own, limited preconceptions? Or can it find a way out of the murk, and re-learn how to combine glossy, mass-market popcorn appeal with a more considered approach to craft? There are definitely signs of hope. For a good while now, several big studios have been running indie-focused sub-labels, in order to distribute smaller and more interesting films to a bigger audience than they might possibly otherwise have had. Fox Searchlight has been doing great work in this area for a long time - releasing everything from Sexy Beast, to 28 Days Later, to Birdman - as has Sony Pictures Classics, distributor of Howard’s End, House of Flying Daggers, Synecdoche, New York, and many, many more. This does get more niche, more artistic film into cinemas, and is a vital and laudable initiative by both studios.

It does, however, come with a slight aura of segregation, an implicit labelling of some films as ‘mainstream, big deal properties’, while others are, well, ‘the other stuff’. The fact that these distribution options exist is obviously a wonderful thing, but I can’t help wondering how much mainstream audience perceptions might change in the long-term if there wasn’t such ambient compartmentalisation. If there weren’t ‘these films’ and ‘those films’, but rather just ‘the films we release’.

And on the unabashed blockbuster side? The current, most positive endgame is probably the Marvel Cinematic Universe. In many ways, the ultimate version of all of Hollywood’s most cynical predilections for pre-packaged success, its appeal to the business side is obvious. Recognisable characters who have been in the global public consciousness for decades. Almost endless, pre-existing material to adapt into interconnected, ongoing stories to turn into sequels, prequels, teasers and long-term movie arcs. Colossal visual spectacle. It should be the worst. On paper it’s a Hollywood dullard’s dream come true. A final, monolithic totem-cum-gravestone planted to mark the end-days of mainstream cinematic creativity.

But miraculously, its quality has been pretty high so far – albeit with definite variability – aided undeniably by the staunch, creative control of Marvel itself. That’s the unique thing that makes the MCU entirely different from previous products of the Hollywood license churn. It avoids the usual adaptation decay because it is tillered by exactly the people responsible for the original works. The ones at the purer end of the creative production line. The ones who really understand the material. The MCU is still an engine of profit, but it has so far managed to be that while also delivering vibrant, worthwhile material.

But even the MCU is not flawless, or anything approaching a bulletproof solution. While the films are largely good and do well at the box office, eight years in, definite cracks are beginning to show. Because for all of its creativity and relative independence, Marvel’s output is starting to present safe, generic patterns of its own.

Repeat build-ups to repeat apocalypses are becoming rife as the MCU fights a visual arms race with itself – and this is only set to step up further with the Infinity War arc due to kick off over the next couple of years. We’re seeing encroaching fetishisation of cameos from familiar, much loved characters, as new sub-series are launched and Marvel presumably seeks to couch those launches in comfortable familiarity.

And dear God, it would be delightful to see a new MCU film in which no-one drops a single, sarcastic quip. Or even one where half the script doesn’t seem to be made of them. Because hey, Iron Man started it all off, right? And everyone loves pithy Tony Stark. The MCU’s subject matter and locations might change and expand, but the tone is starting to feel uncomfortably cookie-cutter, despite notable, stand-out digressions like Captain America: The Winter Soldier. Marvel needs to be very careful of that as it continues into its next phase.

And tragically, and perhaps inevitably, Marvel’s work has now led to another spin-off wave of modern Hollywood’s worst behaviour. The DC Extended Universe. Which, so far, is just awful and entirely the product of every piece of wrong-headed, under-considered Hollywood thinking that has led us to this point in the article.

Because Warner Bros. and DC wanted their own version of the MCU, and they failed to understand how or why the MCU had become the appealing juggernaut it has. After years of concentrating on the – yes – safe-bet Batman, they had lost a staggering amount of ground to Marvel, which had spent the time gradually laying the foundations of a more organic, wider world. The MCU is plausible and exciting because of that slow build, and the very deliberate development of characters, and seeding of concepts, and the threading of storylines. But Warner Bros. and DC wanted their own version of the MCU, and they wanted it now, and so they did what bad Hollywood has been doing for decades. They fast-tracked something superficially similar and hoped that it would be the same.

That something was Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. A film that impatiently smashed three new iterations of big-name characters together, while attempting to establish a wider, cosmic universe at the same time, and set up multiple sequels following different characters. Including a few who were barely even in the movie. And so, the worst of mainstream, modern Hollywood did respawn from the influence of the best. And the loop began again. And the snake started looking for a packet of Tums.

Are we doomed? I don’t think so. I hope not. Because for all of the major, long-established problems inherent to its workings, modern Hollywood is not completely populated by cynical money-men. Not by a long way. Rather, it is a place where a lot of good, talented people also try to do the best they can within the restrictions of the system. They’re in there. They’re working. They want to get fresh, interesting films out to a wider audience. Both sides of the equation need to reconcile and work better together, but a sensible collaboration can be formed.

The safer, more conservative part of Hollywood needs to open its mind, and embrace the way things are now, rather than the way they used to be. It needs to get more readily on-board with modern distribution methods, and use them as a more standardised means of getting its films out. One that would actually increase potential audience numbers without parallel cost. It needs to stop being scared of Netflix – better international catalogues, with country-to-country parity are a must, as is the cessation of piracy-branding for (paying) VPN users simply dissatisfied with the selection in their country – and start using digital for day-and-date, multiformat releases.

Of course seeing a film on the big screen, in a darkened room, sharing in the reverence of an appreciative audience, is the best way of truly experiencing a movie. It’s the most immersive, affecting, powerful, sensorily exciting experience around. But the fact is that not everyone is going for it. And so Hollywood needs to find ways to get its films to cinema-averse audiences – of which there are many kinds, from the blockbusterphobic, to the simply time-starved – without making them feel like poor relations.

That way, it can increase revenue in a genuinely audience-minded way, create a cost-effective way of surfacing more niche films, and use the combination of the two to fuel production of more eclectic output for every kind of screen. It needs to stop seeing cinema as just what happens in the cinema – and by definition, what (it thinks) is big, shiny and recognisable enough to motivate people to leave their houses - and start seeing it as what it is. A limitless, beautiful, eclectic medium that can and will do anything, for anyone, in any way they want to experience it.

And by doing that, and profiting from it, it might find itself a lot freer to actually get the kinds of film into the cinema that regularly appeal to the kind of people who care about film enough to actually go to the cinema. Get that simple thought locked into the production and distribution process, and Hollywood might well find that everything gets a lot easier, everyone gets a lot happier, and, yes, most importantly, it still manages to make a fair old amount of money along the way.