The creators of Amnesia want to fix what Resident Evil and Silent Hill broke

"Do not employ sliding block puzzles. Ever. That includes sliding statues! No!" advises an essay on Useful Tips for Horror Game Designers, written by Frictional Games Co-founder Thomas Grip (in cooperation with Robot Invader CEO and Co-Founder Chris Pruett), and hosted on the Frictional Games blog. If those names sound familiar, it's because Frictional is the studio behind one of the most famous horror games in recent memory - Amnesia: The Dark Descent - as well as the less well-known but highly regarded Penumbra series. A studio steeped in all that is horror, its team isn't afraid to be upfront about what the genre's doing well and where it's gone wrong, often with pinpoint accuracy: "Don't blame everything on evil mega-corporations. There are other ways to block a passage off than having the roof collapse. Horror games work surprisingly well without rocket launchers."

Vote for Soma in the Best Storytelling, Best Original Game, and Best Visual Design categories at the upcoming Golden Joystick Awards 2016 and claim three games for $1 / £1 for taking part.

This year, Frictional is breaking new ground with their upcoming title, machine-based chiller SOMA; not only is it the first game the team has developed since Amnesia's blowout success (Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs was published by Frictional, but was co-developed with The Chinese Room), but it's also their first title ever produced for console. Even with those changes, the team's main goal remains the same: create the ultimate horror game, unhampered by the distracting trends that too many horror titles embrace.

Grip admits that wasn't always the studio's mission - back when the good ship Frictional first launched with a crew of three (Grip, Frictional Co-founder Jens Nilsson, and Art Director Anton Adamse), the goal was just to stay afloat. "I was really interested in making horror games, and felt that we could do things differently than what was the norm. But that was sort of secondary. The top thing was: 'Can we make money from this?'" Grip told GamesRadar+ in a recent interview. Luckily, the studio had a leg up on the competition: the Penumbra tech demo, which would eventually become Penumbra: Overture, received widespread acclaim as a horror title of its own in 2006.

Most of that praise centered on Frictional's unique means of creating immersive terror - which meant not adopting the standard set pieces and techniques favored by horror behemoths like Resident Evil, Silent Hill, or Clock Tower. While the general consensus is that those games are leave-the-hall-light-on scary, Grip claims that the way they're played hamstrings their ability to be truly horrifying: "Historically, there have been (very broadly defined) two types of horror games. The Myst-style ones that relied on puzzles and the Resident-Evil ones that relied on action…What both of these have in common is that they focus on something very 'gamey' to be at the core of the experience…The actual horror atmosphere is a sort of secondary thing."

That claim is leveled at modern titles as much as the classics: a recent post on the company's blog took issue with new horror darling Alien Isolation for bringing you face-to-face with the Xenomorph way (way, way) too often. The Frictional team is critical of any mechanics that distract from the tension a horror game should be building - inserting a counterintuitive puzzle might pad a game's runtime, and shooting mechanics give you more to do, but both diffuse tension when it's the job of a good horror game to keep it constant. Instead, Grip praises the likes of Slender, Hide, and Outlast for focusing on building tension first and favoring player control over cinematics. That, ultimately, is what Frictional is intent on bringing to the forefront with their own work.

That desire to create a truly terrifying, frill-free horror game is what led to the birth of Amnesia, which is still regarded as one of the best horror games of all time. "It is always really hard to say exactly why a game connects with people, and we certainly never expected it to become as big as it got. But I think that the biggest factor is that the game moves away from being very gameplay focused at the core," says Grip. "What we tried to do in Amnesia was to make the horror the primary focus [and] there are three way in which we tried to achieve this: removal of trial and error (events lose a lot of the tension if you have to relive them), sensory deprivation, [and] ambiance over challenge. When we started the game the main purpose of systems like lamp oil and sanity was to present a challenge. But later in development we changed this so they become more ambient features, making sure the player had focus where it mattered - on the horror."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But Grip admits that Frictional's efforts to create the ideal horror experience haven't been perfect, and the team is just as critical of their own work as the games they've critiqued. They recognize that the Penumbra series suffered from ungainly controls that can break the tension for players when they start to get frustrated, and Amnesia wasn't everything it could have been thematically. In fact, for all of Amnesia's positives, much of what inspired it is unrecognizable in the final product. According to Grip, "Amnesia was supposed to be about the nature of evil. There was a lot of inspiration from stuff like The Stanford Prison and Milgram experiments, and it was meant to be a big part of the game. But the problem was that the final game did not really have much focus on it. It was more of a vague background element and that felt like a failure to me."

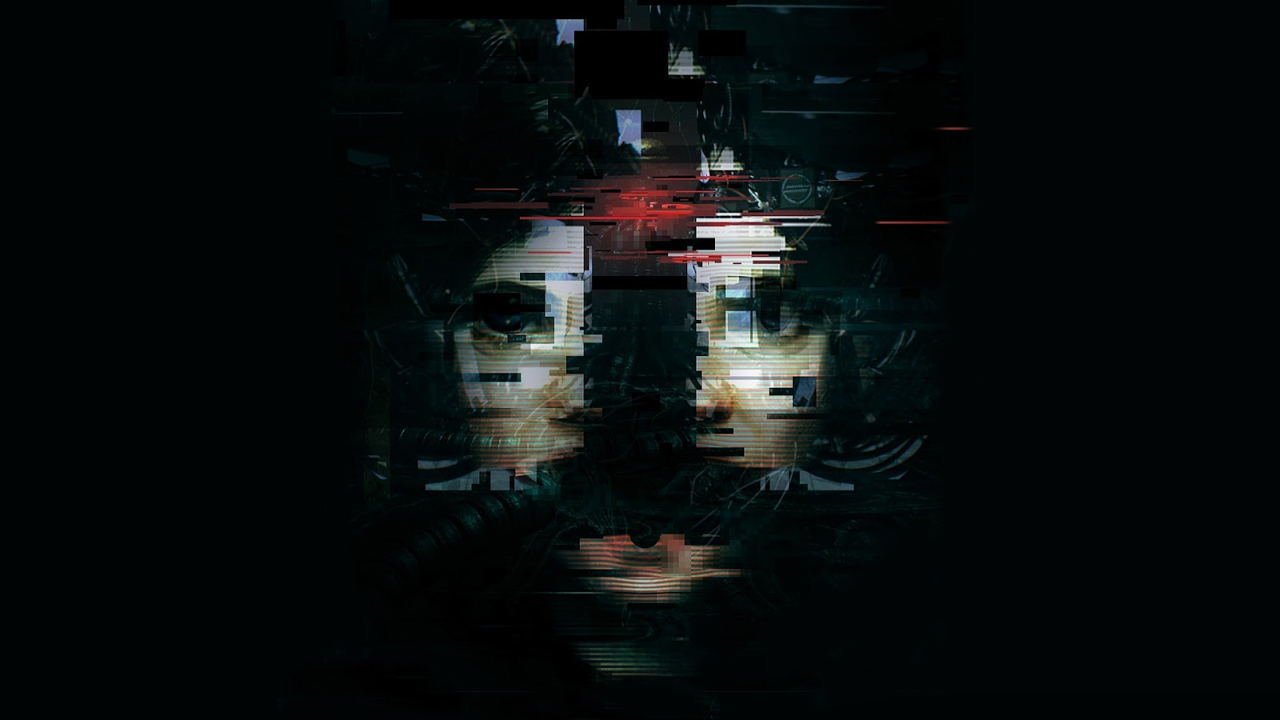

Balancing that sort of many-layered story, player agency, and carefully maintained terror is no easy task, and creating the ideal horror game that Frictional is striving for is a process of evolution. That brings us to SOMA, set in a mysterious underwater facility where the computers seem to think they're human - and, terrifyingly, they might be right. Determined not to make the same mistake they did with Amnesia, the Frictional team was quick to highlight SOMA's story-centric aspects in its announcement trailer, which contains as much talking as it does loud thumps and shaky camera angles. "The themes that we want to discuss in SOMA - consciousness, identity and in some ways, the nature of reality - are meant to be what the game is about, not just some background fluff that you can ignore," says Grip. "So we have worked hard to make sure that those things are part of the actual gameplay and something that the player needs to confront head-on when playing the game."

Even trickier, Frictional's plan is to make those story elements the driving source behind SOMA's horror. "Most of [Amnesia's] scares were all about inducing primal 'afraid of the dark'-like responses. SOMA, on the other hand, derives much of its horror from the subject matter," Grip noted in a recent response to fan queries. "The real terror will not just come from hard-wired gut reactions, but from thinking about your situation and the events that unfold from it." Taking a cerebral approach means the game can't rely purely on players' instincts to drive their fear - the story elements have to be truly scary in order to convince your higher brain that yes, you should keep being afraid.

But Frictional seems to be on the right path, because above all else, they're looking to combat one of their (and horror in general's) biggest weaknesses: dwindling returns. "In Amnesia: The Dark Descent, there's constant oppression that starts from the get go, peaks somewhere half-way through, and then continues until the end. What you get is a game that's very nerve-wracking, but which also becomes numbing after while," Grip admits. "It's pretty common for players to feel the game loses much of its impact halfway through. SOMA is laid out a bit differently. At first it relies more on a mysterious and creepy tone, slowly ramps up the scariness, and peaks pretty late in the game."

Next year will be the ten-year anniversary of the Penumbra tech demo's release, and a lot has changed for Frictional in that time. But one thing Grip says hasn't changed since those early days is Frictional's constant quest to make the best, scariest game that they can, and always shoot for that ideal where others take the safe and easy route. "The core creative vision, to explore what can be done with horror games, has not really changed since it first came about," says Grip. "We still feel there is a ton of stuff that can be done to progress the genre and we like to be at forefront of doing that."

Former Associate Editor at GamesRadar, Ashley is now Lead Writer at Respawn working on Apex Legends. She's a lover of FPS titles, horror games, and stealth games. If you can see her, you're already dead.