What gaming's lack of human stars says about its lack of humanity

This piece is about games and stars - or rather, about games and their lack of stars, in the Hollywood sense. Games arguably have their own version - celebrities, performers and notables - but none, I will argue with devastating eloquence and reference to European intellectuals for added gravitas, who function in the same way as stars of the screen, those luminary bodies who give a meaning and a humanity to their work which extends beyond the fiction and connects it to us, and us to them.

But let’s begin with a bit of telly.

Very few things will give you as accurate a read on how the sluggish mass consciousness of Western culture views a particular object as an episode of formulaic network television. Recently Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, which has a tradition of taking on stories inspired by the headlines, did an episode about games, GamerGate, women developers and harassment.

The show is concise, tabloidy, middle-aged and mainstream. Ideas pushed through the intellectual mesh of Law & Order typically end up pureed into a special kind of stupid, and this was no different. The general consensus was that everybody lost - the developers whose stories were trivialised for pacy drama, the community who were once again subjected to a tedious ‘can they tell the difference between reality and a game?’ non-controversy, and everyone watching for having the basic language of games clumsily explained by Ice-T every few minutes.

Whatever your stance on the events that inspired the episode, one thing illustrated with an alarming clarity is that while games are now a bigger business than movies, books and music, wider perceptions of the medium remain distant and dated. This episode - its Call Of Duty surrogate Kill Or Be Slaughtered, its Amazonian Warriors, harrassed women and deluded rapists - is, crudely and imperfectly but with a central gut-punch of truth, a snapshot of what they think of us.

What I took away from this is that, yes, the snapshot is bad. Perhaps rightfully so. But more troubling and interesting is why it’s only a snapshot. Why don’t games have the kind of perpetual presence of other entertainment media? And at least part of the answer is the lack of stars - the lack of people - in games.

Independent producers, like Carl Leammle, who went on to found Universal Studios, grasped more fully the romantic possibilities of stars. Leammle tempted Florence Lawrence away from her contract with the Motion Picture Patents Company and took her on a tour of America, planting reports in the local press announcing her death, and taking out advertisments the next day denouncing the reports as the malicious work of the jilted Company.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

That’s how the story goes, anyway. The truth of stars and the establishment of the studios which still dominate Hollywood is more complex, but lacks the dash and swagger of Leammle’s brass balls. The point is that stories are important, and stars are a way of telling them. When Leammle pulled his trick with the press he was constructing one of the first star images, transforming Lawrence into something more useful, seductive and compelling than a lady who sometimes pretends to be someone else.

Leammle’s trick was eventually parleyed into a thriving sub-industry within Hollywood. Studio-era stars had full-time publicists whose job it was to fix the stars’ look, hair, clothes, quotes, and even lovelife. They would write stories for gossip magazines, invent romances with other stars - the invented persona would be an exaggerated amalgam of the stars’ onscreen image built on the fragile wireframe of their real selves.

This is important for a couple of reasons. First, the experience of cinema didn’t - and doesn’t - end when the film does. Some of the meaning of film, the things we think and feel as we stare at the screen and internalise the stories and images it conveys to us, some of that meaning is transferred to the star. And the star is persistent. They still exist when the film ends. The star image, that projection of a being halfway between the small, real actor and the giant characters they charisma-inflate into existence, roams detached from both reality and fiction.

Second, it’s important because these idealised stars became a crucial point of connection and significance for audiences. They still are. Stars are mechanisms of reflection and fantasy, ways of seeing ourselves and who we might be. What makes us respond emotionally when we watch stories on a screen - what makes us feel - is that we could be them. It is - and I’m sorry if this sounds like over-sharing but I feel like a hug right now - about being human.

The reason these things in particular are important is because games don’t have them. Not having stars means the conversation stops when the game does. The publicity machine of old Hollywood is still alive today, in the not-that-altered form of gossip weeklies, the Daily Mail sidebar of shame, and Reddit threads about which celebrity is ‘a solid guy IRL’ (the answer is Keanu Reeves). For millions of people who may only watch a film or two a year, the tides of blockbuster season and the ups and downs of celebrities are part of a ticker-tape conversation that streams across all forms of traditional and social media, enabled by the function of stars. And games are locked out of this conversation.

Games, as we touched upon earlier, do have celebrities of their own. But I’d argue that all varieties fall short of the regular Hollywood model. There are voice-over artists and performance capture actors, and in the areas of development devoted to a specific kind of broadly realistic cutscene-driven storytelling some of these performers have gained a following. And why not? Nolan North and Troy Baker are celebrated and ubiquitous, and have done great work in excellent games.

But their ubiquity tells a story - they are unique cases with no framework of stardom to support them. And theirs is an insular sort of fame, limited by their shifting virtual appearances - a pixellated ceiling - to their home industry. Nobody outside games really knows these guys, and they don’t carry games into the mainstream.

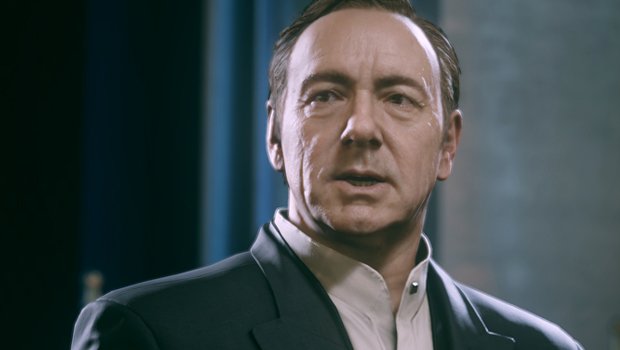

Sometimes, as if to solve this problem, games feature established stars. Sometimes this is because marketing teams like having talking points and things to hang coverage on, even if that thing is an actor who came in for a couple of voice sessions and is unrecognisable in the finished game. This seems a peculiar dead-end of celebrity to me, a gimmick in the old tradition of grasping for synergy that should - surely? - exist between films and games and doesn’t really. Even when the guest-starring is roundly considered a success - I’d offer Kevin Spacey having fun in Advanced Warfare - there’s an ultimate futility to it. He won’t be back, the effect won’t be sustained. These are all one-off bumps of coverage that don’t tie games into any meaningful ongoing dialogue with outside culture.

There are other alternatives too. We celebrate developers and designers, but even the Kojimas, Miyamotos, Newells and Notches are nobodies to a broad audience. And then there are YouTubers, who, with their intense one-to-one relationship with the camera definitely do operate in the many of the same ways as traditional stars - in a kind of perpetual close-up, revealed and accessible, objects of sympathy and fantasy. But they are not stars of games, they are stars around them, who might set up second channels about make-up or collectible toys or the next thing that comes into their minds. They are not bound to games in the same way stars are to the screen - their medium is YouTube.

The point I’m driving at here is that I think it’s impossible for games to have stars, and everything they mean. Games are inherently non-human, and stars are a rarefied spectacle of humanity. I’m not even sure this is a bad thing.

That European intellectual I promised, his name is Béla Balázs. He was a Hungarian film critic who saw a special significance in the close-up. The close-up was important to meaning in the cinema because it was something that theatre couldn’t offer, an intimacy-through-technology that brought the stars into sharper focus. He described close-ups as a sort of “silent monologue” in which

“...the solitary human soul can find a tongue more candid and uninhibited than in any spoken soliloquy, for it speaks instinctively, sub-consciously. The language of the face cannot be suppressed or controlled.”

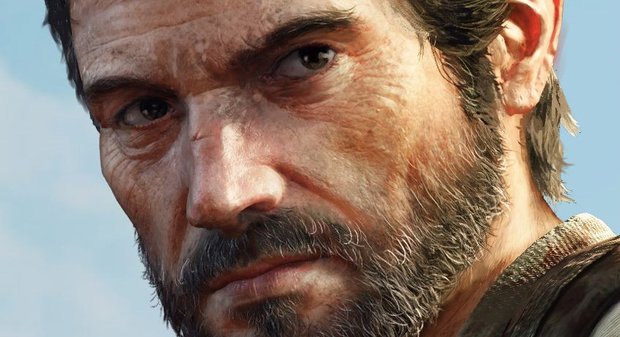

The reason I like this quote is that it emphasises the human nature of stardom. The face is endlessly readable and interpretable and mysterious. And in that way, the close-up, copied by games as part of the borrowing of the language of cinema, makes the inhumanity of games transparent. Because it’s impossible to read this quote, then think about a close-up in a game - Kevin Spacey’s dramatic turn to the camera in the Advanced Warfare trailer is my favourite - and not see that close-up as a sort of grotesque parody of humanity, a blank dead lump of pixels that can’t help but mock the sophistication of the real thing.

Why are games trying to be human, or photorealistic? A good guess is because cinema has always been there, a deceptively similar-looking medium of technology and unreality that offered a path to follow. And because games are subject to the surging ambition and egotism of technology, and photorealism - recreating people that weren’t instantly laughable - was something to shoot for. It’s only now, after 30 years, when games can make hugely sophisticated models of people that nevertheless remain, in the slow meaningful turn of the head and the plastic flex of a cheek muscle, ultimately artificial, that we should probably ask - was it worth it?

And I would answer, no. The hunt for stars is a hunt for humanity games don’t possess. And that’s fine, because games can be anything they want to be. Chasing after this particular way of expressing and connecting to things - spending all this time and effort recreating ourselves in doomed but intricate ways - is a mad waste, when games can go anywhere and show us anything. I’ve felt equally strong emotional connections to rudimentary sprites, graphical icons and jumping squares as I have to the most real unreal people games can offer. The chase is a folly. Games should cut the cord and embrace their lack of stars, and get on with defining our relationship with the universe in a thousand other ways.