What Studio Ghibli has to teach us about climate change

As the Studio Ghibli movies reach Netflix, we reflect on what they can teach us about climate change

When Hayao Miyazaki co-founded Studio Ghibli in 1985, the legendary animator probably never imagined that his movies would one day sit alongside TV shows about cheerleading teen witches, crusty British royalty, and makeover enthusiasts. Yet, here we are. The studio’s back catalogue is being made available on Netflix over the next few months (all except 1988’s The Grave of the Fireflies, which it technically doesn’t own the rights to) and, while some of the films may be decades old, their availability on the world’s largest streaming service seems particularly timely.

We’re living through an age where, finally, thanks to activists like Greta Thunberg, climate change has been pushed to the forefront of the global conversation. It’s hard to look at the news without seeing the rise in floods, droughts, and wildfires as a dire warning that our planet has been broken – and we may be too late to fix it. The future looks bleak. Since day one, though, Studio Ghibli has preached environmentalism with a sense of nuance and grace that’s unlike anything we’ve seen in Western cinema.

The company was originally founded following a massive economic boom for Japan, in which rural farming communities were gradually consumed by industrialisation and urbanisation. What was once idyllic countryside became a spider’s web of smoke-spewing factories and traffic-choked roads. Ghibli movies are often nostalgic for a time when mankind coexisted peacefully with the world’s other inhabitants. But, more crucially, they ardently believe that this harmony can be achieved again. It’s the perfect time for audiences to discover (and rediscover) Studio Ghibli, because we need that same hope – now more than ever.

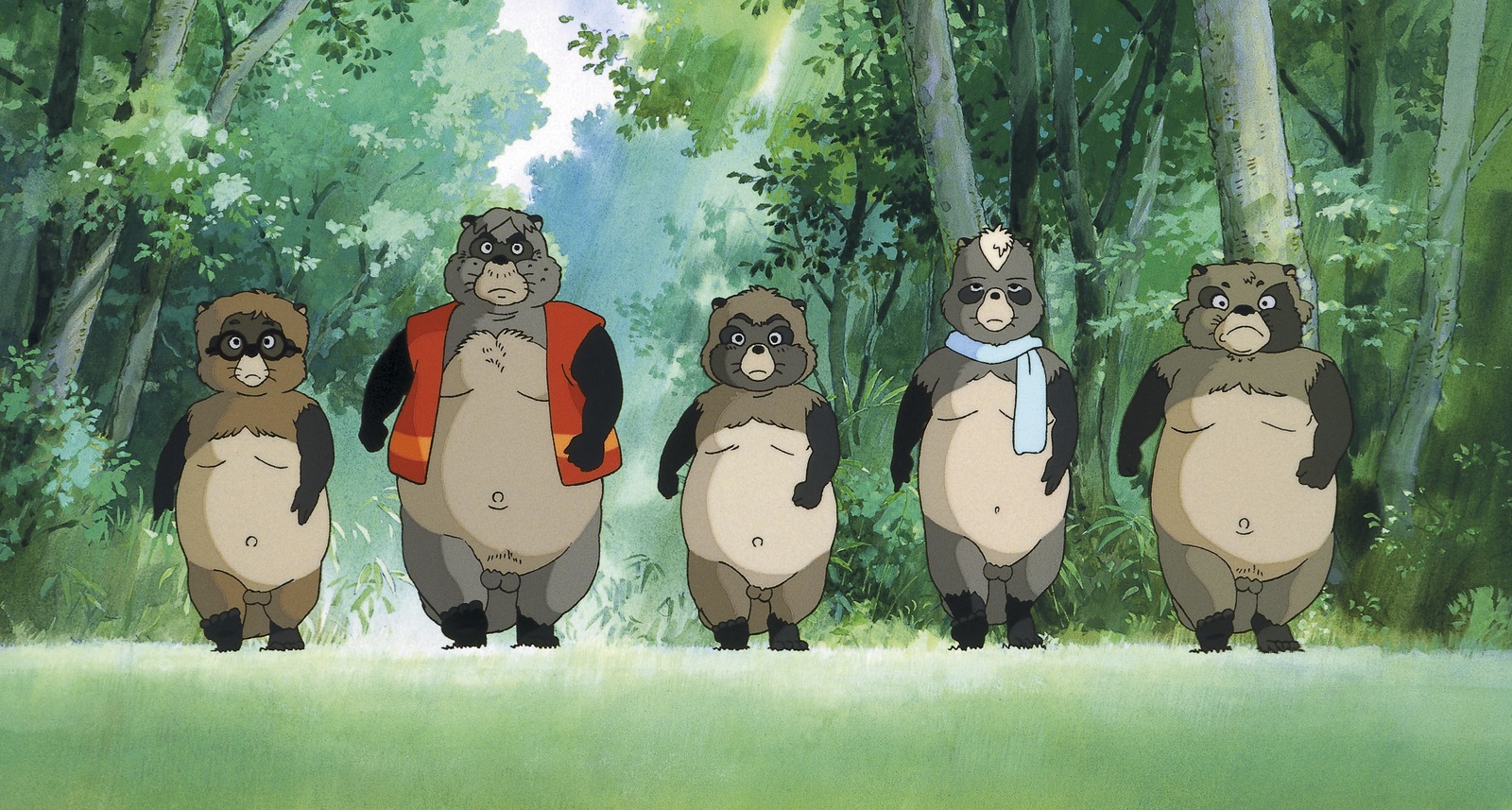

In 1994’s Pom Poko, directed by Isao Takahata, there’s a direct call-to-arms delivered by a clan of tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs). In the movie, the woodland habitat has been largely destroyed by Tokyo’s expanding urban development. The tanuki – who are known as shape-shifters in Japanese folklore – band together to fight back, and they try all kinds of tricks to convince the humans to stop causing carnage. Unfortunately, they fail. At this point, one of the creatures turns to the viewer and implores us to protect the homes of the tanuki and other wildlife. While the cynics among us may hopelessly blame governments and corporations when it comes to environmental destruction, Studio Ghibli ardently believes individual actions can make a difference.

A similar point is made in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, from 2001. One of the film’s most memorable sequences sees a “stink spirit” – a sickly, living sludge – force its way into the bathhouse and into its largest tub. As the creature soaks, the leading character Chihiro notices an object poking out of its side and decides to tug at it. A deluge of waste pours out. There’s a bicycle, a fridge, and a children’s slide. As the creature purifies itself, Chihiro realises she’s actually looking at a river spirit that’s been transformed by human pollution.

According to Miyazaki, the scene is inspired by his own experience volunteering to clean up a river, which allowed the fish to return and repopulate the area. Although a small act of kindness may not confront the bigger problems at hand (like why pollution exists in the first place), Miyazaki still sees respect for the planet as the essential building blocks for a better world. Everyone has to start somewhere.

Interestingly, Miyazaki has denied that his films are explicitly religious, yet it’s hard not to draw a connection here with Shintoism, an indigenous belief system in Japan that predates the existence of historical records. Supernatural creatures like Totoro, from 1988’s My Neighbour Totoro, appear to be kami, the spirits that are said to inhabit all aspects of nature. With his toothy grin and wide-set eyes, Totoro is certainly cute and cuddly. No wonder Mei, the local girl who discovers his lair, is so keen to make friends with him.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

But this beast is also the venerable “Keeper of the Forest”, who sleeps each night in a sacred camphor tree. His roars unleash howling gusts of wind. Shintoism doesn’t have any kind of central scripture, so worship is largely a private act. Followers might stop by a shrine once a day to offer the kami a silent prayer. Much like Mei’s dedication to Totoro, or Chihiro’s favour to the river spirit, each person’s connection with nature is viewed as both intimate and reciprocal. When that bond is broken, all hell breaks loose.

Ghibli movies are often sweet, but they aren’t overly sentimental. Princess Mononoke, released in 1997, is one of the darkest and most violent of the studio’s creations. The movie sees Iron Town founder carve further into the forest, sapping its resources in order to let her people flourish. The spirits have no choice but to retaliate. Cowering behind Iron Town’s great walls, they’ve become corrupted beyond recognition. Once a mighty boar god, Nago is now a demon who spews toxic, black tar.

The destruction (and, most importantly, impending destruction) caused by climate change is nothing but a scientific chain reaction, but in a poet’s eyes – it’s the planet biting back, like a dog whose tail has just been stepped on. In Princess Mononoke’s climax, Iron Town is flattened and Lady Eboshi is left with a revelation: when mankind destroys nature, it only destroys itself. Eboshi and her people rebuilt their settlement, but vow no longer to work against the forest. They must find a way to coexist; only then can they find the peace and unity spoken about it Shintoism.

Unlike Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki’s 1984 film Nausicaä Valley of the Wind is set long after nature has had its revenge. The landscape is now littered with the gigantic, horned skulls of the God Warriors, who were created by mankind and caused the Seven Days of Fire – an apocalyptic event responsible for wiping out society. Most of the world is now uninhabitable, infected with toxic forests and enormous insects. But the princess Nausicaä, the saviour “clothed in blue robe” mentioned in a prophecy, is the only one brave enough to venture out into the wilderness and communicate with its creatures.

She discovers that the forest plants are, in fact, purifying the polluted soil. There is hope. The earth can renew itself, but Nausicaä’s community must learn to develop technology in ways that show benevolence and care towards the planet. They must look to the windmills and Nausicaä’s trusty glider, which don’t attempt to harness the wind but work in tandem with it. Miyazaki is a traditionalist and environmentalist, but he’s never been a technophobe. He only believes that technological advancement shouldn’t come at the expense of the world around us.

As the director once said: “There is no order to impose on the living beings. We respect nature such as it is, and not such as it should be.” As we seek ways to combat the effects of climate change, it would be wise to remember the lessons of Studio Ghibli’s beautiful, uplifting films. Nature is humanity’s ally – we should treat it that way.

Want to check out what's new on Netflix? Then here are all the best new Netflix movies and shows you should watch.

Clarisse is a freelance film journalist, and is a film critic for The Independent. She also writes in a freelance capacity for a number of publications such as GamesRadar and Total Film, and is the co-host for the Fade to Black Podcast. She also runs her own YouTube channel focused on film reviews.