How Red Dead Redemption 2 lays down a path to utopia

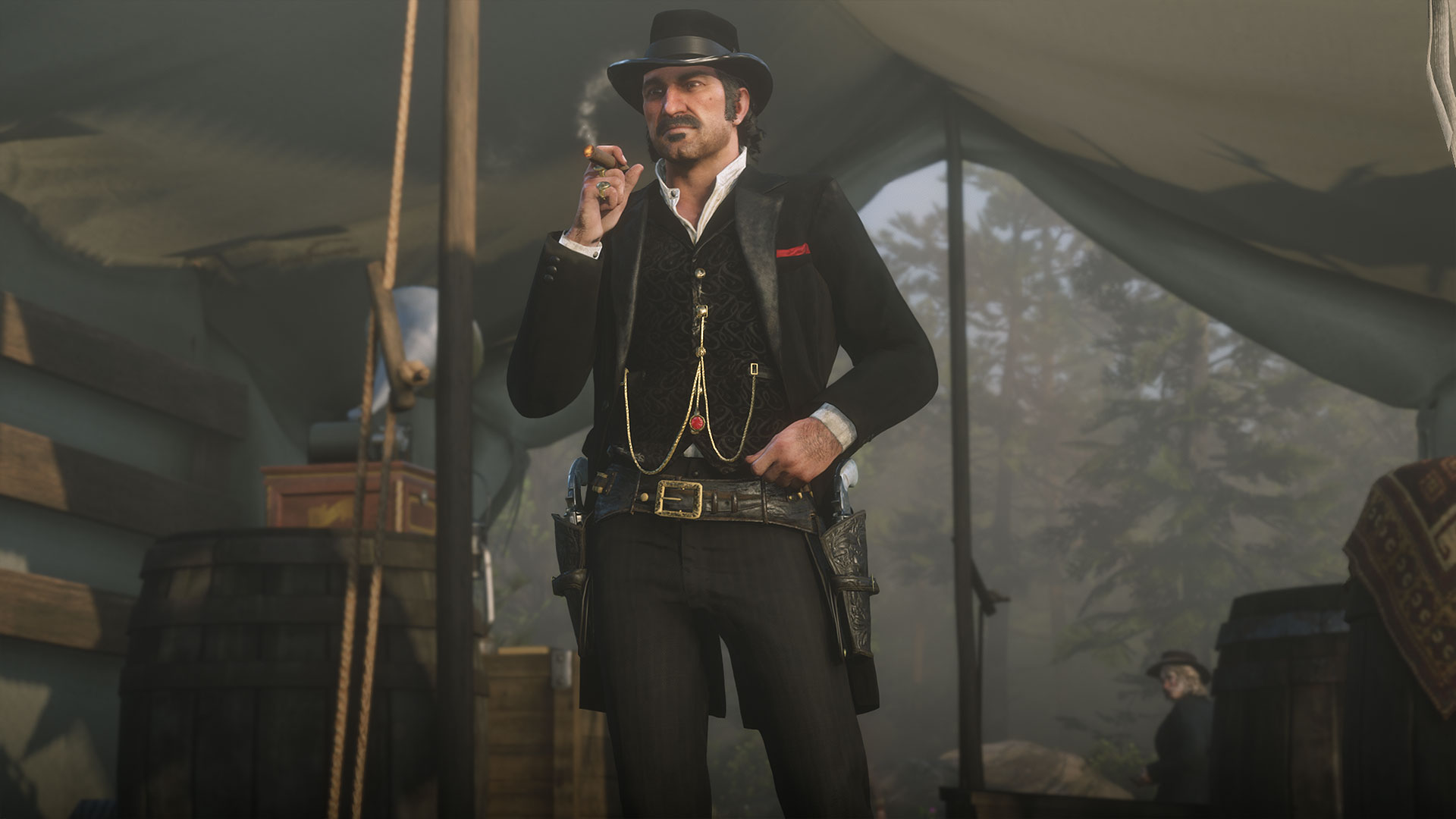

Dutch has a plan, but is it one that ever stood any chance at succeeding?

Dutch van der Linde, the leader of the Van der Linde gang, is an avowed utopian. He declares that his goal is no less than to reform society. He says that he detests the word “real” and describes the gang as “dreamers in an ever duller world of facts”. This does not necessarily mean, as critics of utopia would tell you, that Dutch cannot face reality. Dutch recognises the transformative political potential of dreaming and he expresses as much throughout Red Dead Redemption 2. To dare to imagine alternatives is to recognise that the world could be different – it's the first step on the path to make it so. Dutch’s contempt for “realism” stems from his awareness that calls to be “realistic” can be used to shut down these avenues of possibility in service of defending the status quo. It was once “unrealistic” to imagine ending the divine right of power wielded by kings, or the brutal practice of slavery; These were once dreams, until people made them reality.

Hence, the Van der Linde gang. The gang is, what scholars of utopia would call, an intentional community. That is, a group of individuals that choose to live together, usually in service of some kind of goal or principle, often living communally, working together and sharing resources. In Dutch’s view, this community is an expression of a dream – a vision of a different way of living.

A path to a new tomorrow

In opposition to the way society at large operates in Red Dead 2’s version of late nineteenth century America, the Van der Linde gang is one where food, medicine and other provisions belong not to the individual, but to the community. Each member is free to take what they need from these common supplies. In turn, they are expected to contribute; A share of any money they make going into common funds and additional voluntary contributions are encouraged. This set-up has more in common with communist or anarchist traditions than either the emerging capitalist society Red Dead 2 is set in or the staunch individualist survivalism we might associate with the wild west frontier fiction that the Red Dead series draws on. The game does a great job of making us feel committed to this way of living, too – you feel a sense of guilt if you ransack the community’s food supplies without compensating by paying for a refill, or taking down a deer and delivering it to the table of the camp’s grateful cook.

We sit down with voice artist Alex McKenna to get exclusive insight into the making of Red Dead Redemption 2's incredible Mrs. Sadie Adler.

The community’s utopian dimensions are also there in its egalitarianism. Lenny and Charles enjoy the kind of mutual support and respect not offered to them in the world outside the gang, where they are at best subjected to the passive hostility of racial hierarchy and at worse threatened with lethal violence. It is true that the community is still a male-dominated space – and that woman like Sadie Adler have to fight to be treated as equal to their male counterparts – but the community’s strong, if ill-defined, commitment to freedom at least means she is not prevented from grabbing a gun and riding out alongside Arthur and co when she insists on doing so. The Van der Linde gang even offers a home for the vulnerable. The community takes up the slack for addicts like Uncle and the Reverend Swanson (admittedly, with some reluctance), offering protection, providing shelter and meeting their basic needs, rather than leaving them to fend for themselves.

The community’s clear opposition to the way the society around it works serves as a reminder that the vision of America that wins out over the Van der Linde gang by the end of the game was not an inevitability. The game re-stages a battle over concepts since won by its enemies and deeply embedded in modern society, asking us to re-evaluate what words like “family”, “property”, and “freedom” could and should mean. This is a valuable utopian exercise.

Strength in numbers

The Van Der Linde gang also showcases the potential strength of the intentional community as a device for change. Rather than arguing that we should live in a certain way, the gang simply does it. This part of Red Dead 2 is not a fiction: There are intentional communities across the world doing the same thing – whether dedicated to sustainable ecological living, co-operative ownership models, or whatever shape that could ultimately take. The members of these communities do not wait for someone else to create a world that operates in accordance with their principles. Instead, they create that world for themselves; They are living evidence of our power to define the future.

"Red Dead Redemption 2 offers no way out of this contradiction, but it does show us where not to go."

However, Red Dead Redemption 2 also highlights one of the major problems of the intentional community: It does not exist without context. The narrative arc that extends across the Red Dead series is that of the end of the West – the idea that modernity, civilisation, or whatever else you want to call it, is closing in as the modern state takes shape. As the law gradually tightens the noose around the Van Der Linde gang’s neck, it is forced to confront the question of how an alternative way of living can exist in a totalising system that doesn’t share its principles. This is a problem that we all face. We might choose to retreat to live in a sustainable eco-village in response to our drive towards climate catastrophe – it would be far easier than reforming the whole of global capitalism – but if that system continues to burn fossil fuels with abandon until extinction, what does our commitment to an environmentally friendly lifestyle ultimately mean?

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Red Dead Redemption 2 offers no way out of this contradiction, but it does show us where not to go. Dutch’s response to the threat the gang faces is to retreat from his utopian ideals into the realm of fantasy. His focus drifts from making utopia in his community to thinking about utopia as a place that already exists elsewhere. He settles on the idea of the gang reaching a tropical paradise to live out the rest of their days in peace and luxury. A hellish detour to Guam that leaves the gang drenched in sweat and blood after becoming involved in an uprising against a tyrannical sugar plantation owner should serve as a reality check – Dutch’s romanticised picture of the tropical island as a realm free from the conflicts, contradictions and hardships the gang faces in America clearly has no basis is reality. Dutch, however, won’t see it; There’s always just one more big job to do before the gang reaches the promised land of Tahiti.

All-consuming delusions

In chasing his delusion, Dutch forgets about what made the community worthwhile in the first place. Any utopian dimension the gang had lay in the bonds between its members and their unconditional commitment to support and protect each other. Dutch loses this commitment, abandoning John, Abigail, and even Arthur as the idea of reaching his fantasy paradise becomes more important that the people that surround him. With these bonds broken, the community inevitably dissolves. The dream is over.

The story of Dutch’s degeneration from utopia to fantasy serves as a fable about displacing our hopes for a better world elsewhere. This happens all the time. Think of those that believe Elon Musk will save us all by colonising Mars, displacing our hopes for the future not only onto a single billionaire, but another planet entirely. Or, think of the way we cite polls showing that young people are more progressive – are against brexit, want action on climate change, or whatever else we might deem a valuable trait – taking solace in the idea that when these kids grow up and take control, things will be different, always shifting responsibility onto the next generation.

Of course, the whole argument of young activists like 16-year old Greta Thunberg is that, in the face of climate change, there is no time to wait for the next generation. The challenges we face as a society are daunting but they must, nonetheless be faced. There is no Tahiti. The burden for creating a better future lies on our shoulders.

Paul Walker-Emig was once a video games journalist, before he moved into PR. During his freelance career, Paul wrote for GamesRadar, The Guardian, Retro Gamer, Wireframe, Kotaku, VICE, VG247, OXM, and more. He runs the Utopian Horizons podcast, which covers a different utopia, dystopia, utopian thinker, or movement each episode. He also runs the podcast getObject, which is a video game website and podcast based around collectible items.