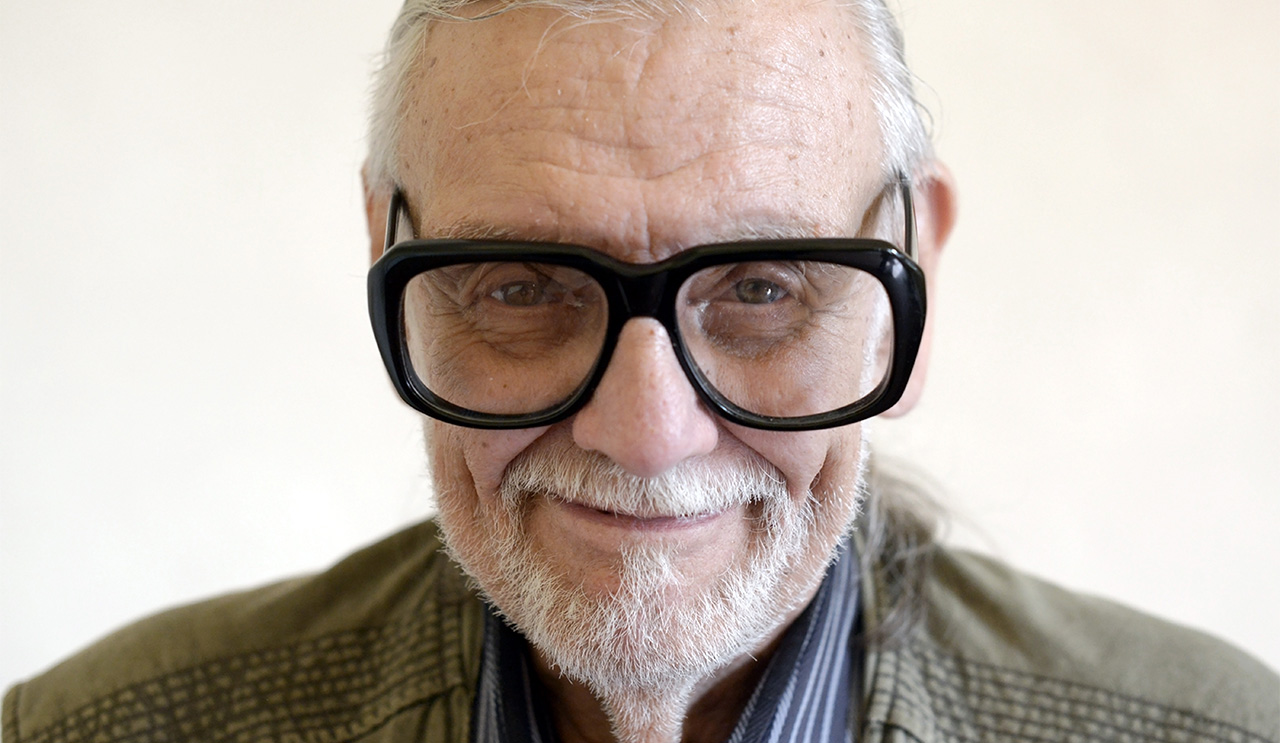

Here's to George A. Romero, otherwise known as the Knight of the Living Dead

The grandaddy of zombies, George Romero passed away at the age of 77 last year. Yet his movies live on, and every zombie we see is a subtle reminder of his influence over the undead genre. On what would have been the filmmaker's 78th birthday, we look back on an interview our sister publication SFX magazine did with the godfather of the shambling undead some years ago. Read on and remember what Romero gave us...

Meeting George Romero is kinda intimidating. Not because he’s a scary fella – dear me, no. You couldn’t hope to meet a nicer guy. It’s partly because he invented the zombie genre as we know it (yeah, zombie films existed pre-Romero but George, bless him, was the one who introduced the vital element of flesh-eating). It’s also an instinctive human reaction to the man’s towering presence – the veteran director stands about 6’ 5” tall. He’s a giant in both senses of the word!

After several years off the radar, Romero is back in the spotlight thanks to the fourth entry in his renowned Dead saga, Land of the Dead. It’s merely the latest leg of a journey that began in 1967, when Romero was knocking out ads for toilet cleaner and washing powder in his native Pittsburgh.

“I’d always been passionate about film, and we started a commercial production company that did commercials, industrial films and the like. So we had the equipment and we said, ‘Why don't we try to make a real movie?’” The result was the horror classic Night of the Living Dead, a bleak tale about the dead inexplicably rising from the grave and besieging an isolated farmhouse. One can’t help imagining what would have happened if George and his production company buddies had made a different film. Is there an alternative universe somewhere where George Romero isn’t synonymous with zombies?

“Oh I'm sure there is somewhere out there! The first film we tried to make, at that same time, was not a horror film. It was this very high-minded, almost Bergmanesque thing, a sort of coming-of-age movie, medieval period, and it borrowed liberally from The Virgin Spring. And no-one understood what we were trying to do! So we said, ‘Well, why don’t we try to do something that’s more obviously commercial?’”

Shedding light on Night of the Living Dead

Night was shot on the cheap using whatever resources Romero and his pals could beg or borrow, in-between commercial jobs. “It was really a labour of love. We had no money and we were relying on the kindness of strangers. We didn’t know that we were up against impossible odds. Had we, we might not have been as bold!”The main location, for example, was a farmhouse awaiting demolition, which had no running water. After 18 hour shoots, Romero slept on site to protect the camera equipment.

“It was real guerrilla stuff, living in that farmhouse and thinking up the next scene. And we finished it entirely in Pittsburgh. In those days the news was on film, so cities the size of Pittsburgh had film labs. So we literally finished the film at home, threw it in the trunk of the car and drove it to New York” George grins at the memory of his youthful naivety, “Just babes in the woods, man! We just had no idea what we were getting into!”

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Over the years, Night has accrued a lot of serious-minded academic readings. Strikingly, the film has a black lead, Ben. He’s often interpreted as representing the Civil Rights movement. “Well, Duane Jones [who played Ben] just happened to be an African American. He was the best actor from among our friends, so we said, ‘Duane, you do it!’, and all we did was not change the script. And I’m not sure that was right! I think we probably should have referenced it. I think we missed a theme there, which is that sometimes an individual in a minority might see things more clearly in some ways, but in other ways a bit more harshly, and maybe over-react, so I’m not even sure that that was correct.”

Which isn’t to say that Night of the Living Dead wasn’t concerned with any big ideas... “In our minds we were making a film that was about revolution. At night we would just sit around and bullshit, and of course we noticed the idea of the destruction of the family unit, and the idea of revolution. We were all pissed off. We all thought the ‘60s were gonna change everything - and of course they didn’t. So a lot of that stuff probably crept in subconsciously. But basically, we were trying to make a horror film, a thrill ride!”

In 1978 Romero followed up Night with Dawn of the Dead, which sees a group of survivors of the zombie apocalypse taking refuge in a shopping mall, where they discover that this consumerist paradise is merely a gilded cage. The film’s anti-consumerist message has made it equally popular with academics. Does it amuse George that people write PhDs about his zombie films?

“It doesn’t make me laugh - in a way it’s very flattering! In the first film it wasn’t so conscious; none of the other ones that I’ve done have been quite as innocent. I decided somewhere along the way, during Dawn of the Dead, ‘Man, I might as well be way up front with it!’ So then people wrote about ‘the hidden messages in Dawn of the Dead’...” George roars with comedy exasperation. “They’re not hidden! They’re in your face! Still, people thought it was somewhere underneath. I mean... God, how in your face could it be? Holing up in a shopping mall? Come on, guys!”

Were his movies satire? Don't be so sure...

George doesn’t see his zombie films as social criticism or satire. “They’re more snapshots, it’s ‘this is my impression of what’s going on now’, and trying to put it into the films thematically, into the story. And at the same time, stylistically - y’know, Dawn of the Dead looks like Saturday Night Fever!” Hang on, does it? I don’t remember any undead guys strutting their stuff in wing-collared white suits. You missed a trick there, George. You should have put some dancing zombies in it! “We should have done! But we didn’t. We had a pie fight, though!”

The third entry in the saga, 1985’s Day of the Dead, was Romero’s snapshot of the Reagan era. It’s set in an underground military bunker, where a group of scientists spend their time bickering with a group of increasingly homicidal soldiers. It’s probably Romero’s bleakest vision of humanity. “It was all about mistrust developing, mistrust not only in institutions but in each other, which seemed to me what was happening then. People losing faith in not only the government, the military, education, but losing faith in each other. It was the beginning of that erosion - y’know, every man for himself.”

All three films seem deeply cynical about human nature. In the face of the zombie threat, instead of cooperating, people invariably argue amongst themselves and turn against one another. So is Romero one of life’s pessimists? “I don’t know, man! No, I’m not very optimistic. Or let me say, I don’t like the odds! I kinda remain optimistic, but I think it comes down to personal choice - I mean, it's who you hang out with isn’t it? That’s really about all you can do, pick your buddies. You can’t pick your place of birth”, he smiles wryly, “or your President, really!”

Romero spent most of the last decade attached to a succession of projects that never got greenlit. Between 1993’s The Dark Half and Land of the Dead, he got one film made – 2000’s Bruiser. And that went straight to video. While he was away, the box office success of zombie flicks made his name a “hot brand” again. Which lead to the film Romero devotees had been waiting for for two decades: Land of the Dead, a snapshot of the post-9/11 landscape.

“It’s not just post-9/11” George corrects. “I think it goes from August 2001 to the Iraq war. When I originally wrote the first draft it was much more about homeland problems - homelessness and AIDS and ignoring the problem. Then 9/11 happened and nobody wanted to touch it, so I just put it away for a while.” In Land of the Dead, a pocket of humanity survives protected on all sides by fences and water. A privileged few live in a gleaming skyscraper. “It’s about that whole period - immediately before 9/11: feeling safe - protected by water. And then the water gets breached - that’s there. We made the tower a little taller...”

Some images that survived from the first draft have acquired extra meaning since Iraq, like the scenes of an armoured truck called Dead Reckoning cutting a bloody swathe through the zombie ‘hood...“The truck was in the original script, images of this armoured vehicle going through a little village mowing people down, then wondering why they’re pissed off! That resonated more after we’d seen the footage on CNN...”

The most interesting thing about Land of the Dead is that George’s zombies are evolving. They learn to use weapons, and band together under a leader, who seems to feel concern for his fellow zombies. It seems like a radical reinvention, but George insists that it’s no big deal. “I was trying to do that even in Dawn, even just through the wardrobe - to give them some character and create that kind of empathy for them. At the end of Dawn there’s a guy that’s been dragging around a gun, and he grabs another gun and decides that’s better - so that’s a little bit of choice.” And Day of the Dead’s starring zombie was Bub, a zombie who’d been trained to perform simple tasks. “Bub was pretty evolved. Bub was imitating the scientists, imitating a human’s behaviour, so I thought the next step was to have other zombies imitating a zombie.”

Romero’s zombie films always have an African American hero – but in this film, he isn’t a human – he’s a zombie called Big Daddy. “I thought, ’If I switch that, well maybe people will understand more clearly that I'm sympathising with these guys now.’ And basically, I always have been!”

What could have been

So the big question is, would George like to do another zombie film? And if so, are we gonna have to wait another 20 years? “If I’m still alive I’d love to make another one - but I’d rather wait until something happens...”

What, wait for the muse to strike? “Or wait for somebody to nuke DC!” The ending of Land is surprising open-ended. The heroes live to fight another day; and the lead zombies live to bite another day, too! Has George got sentimental in his old age? Nah, he was just thinking ahead. “I suppose I had this sort of double purpose. Two things were on my mind: ‘What if this is a big hit and they want another one right away? I’d better leave this open-ended!’ I was thinking that I’ll just do part two of the same story, because I don’t have anything else to talk about, politically - so I’ll just follow the truck or follow the zombies. And if I never got to make another one, I wanted to end on the idea that the only way that this is ever gonna resolve is some sort of a detente - we gotta leave each other alone, or this is never gonna end. So I wanted to put a little bit of that in there, just in case I get hit by a cab or something!”

Whatever does happen next for George (and we sincerely hope it’s not getting crushed under the wheels of a taxi) it seems like his career is finally back on track after all those years mired in the Development Hell quagmire. His next project could be an adaptation of the Stephen King story From a Buick 8. Or it could be, “this new script I’m writing, which there seems to be some interest in.” Or it could be another zombie film. If that’s the path he takes, what can we expect? “I figure that if I have to do it quickly, it’ll probably be about Dead Reckoning. It’ll get a flat tyre or something in a very bad place!”

For more sci-fi interviews, features, and reviews, pick up a copy of the latest SFX magazine or subscribe so you never miss an issue.

Ian Berriman has been working for SFX – the world's leading sci-fi, fantasy and horror magazine – since March 2002. He's also a regular writer for Electronic Sound. Other publications he's contributed to include Total Film, When Saturday Comes, Retro Pop, Horrorville, and What DVD. A life-long Doctor Who fan, he's also a supporter of Hull City, and live-tweets along to BBC Four's Top Of The Pops repeats from his @TOTPFacts account.