Google Stadia points the way to the future, but it might not be around to see it

Stadia is celebrating its first anniversary and Google is ahead of Xbox in the race for cloud gaming, but not to its benefit

Recently, my life changed, albeit in utterly mundane fashion. After years of struggling with a 3Mbps internet connection – the result of an ancient phone line that couldn't be circumvented without moving house – I was finally able to access speeds ten times that. The day after installation, I was playing Orcs Must Die! 3 on Google Stadia, streaming a brand new game directly to a non-gaming laptop, no download required. Bar the odd, momentary drop in visual quality and input latency – which seemed to coincide with fluctuations in my own connection – it worked flawlessly, beaming hectic tower defence straight from Google's servers. Yet the sensible consensus is that Stadia is going to fail, and I'm inclined to agree.

Video games might be rooted in the hard science of coding, but the games industry is full of prophets and evangelists. That's often a good thing: it's a place that feels as if it's constantly on the verge of an exciting future. But as a player, it can be hard to cut through the fervour and work out which of those many possible futures is likely to come to pass.

The future of cloud gaming

History has shown that game developers are susceptible to fads, and part of my job is to sift through the supposed breakthroughs in my inbox to work out what's worth the time of day. A blockchain-powered game store? Don't see it happening. An Atari-adjacent cryptocurrency named the Bushnell Token? Probably not going to set the world alight. The thing about gaming's existence on the cutting edge is that most would-be pioneers tumble over the precipice and into the chasm of forgotten innovations below.

Trickier to ignore are the probable futures. VR, for instance, feels inevitable. The appeal of the holodeck is perpetual, and everybody can understand the magic of putting on a pair of glasses that transport you to another world. The key question is not if it'll be ready, but when – yet the industry has repeatedly jumped the gun. I once interviewed a man named Adam Kraver, with the rather grand games industry job title of Architect. Kraver led a team at Eve Online studio CCP – perhaps the only well-established game developer to go all-in on VR – and was confident that the cost and demands of VR gaming wouldn't hold players back. "It can be fiddly, but guess what, so was my first VCR," he told me in 2016. "If you're passionate about VR and interested in this, you're just gonna do it."

Kraver's game, an interactive take on Tron disc throwing named Sparc, was fantastic. But he was wrong about widespread appetite for VR, just as developers had been in the '90s. CCP ultimately disbanded the Sparc team, and the VR boom ended without touching most gamers' living rooms. The games industry has a hard time seeing beyond its own enthusiasm for pioneering technology – out into a world where cost and convenience matter at least as much as being on the frontier. For Kraver, the future had already arrived, in his home and in his office. And in the last week, with my new connection, I've found myself in a similar position. But I'm predicting a similar outcome for Stadia.

"Just as Oculus and CCP did with VR, Stadia has jumped the gun on the future"

At my last count, Stadia had just under 100 games in its catalogue. Of those, only 31 are free with the Pro subscription, and many more are full price to purchase on top of the monthly fee. Developers and publishers appear to have stayed away, wary of Google's reputation for scrapping new services, and unswayed by the monetary incentive, which one indie told Business Insider was "kind of non-existent".

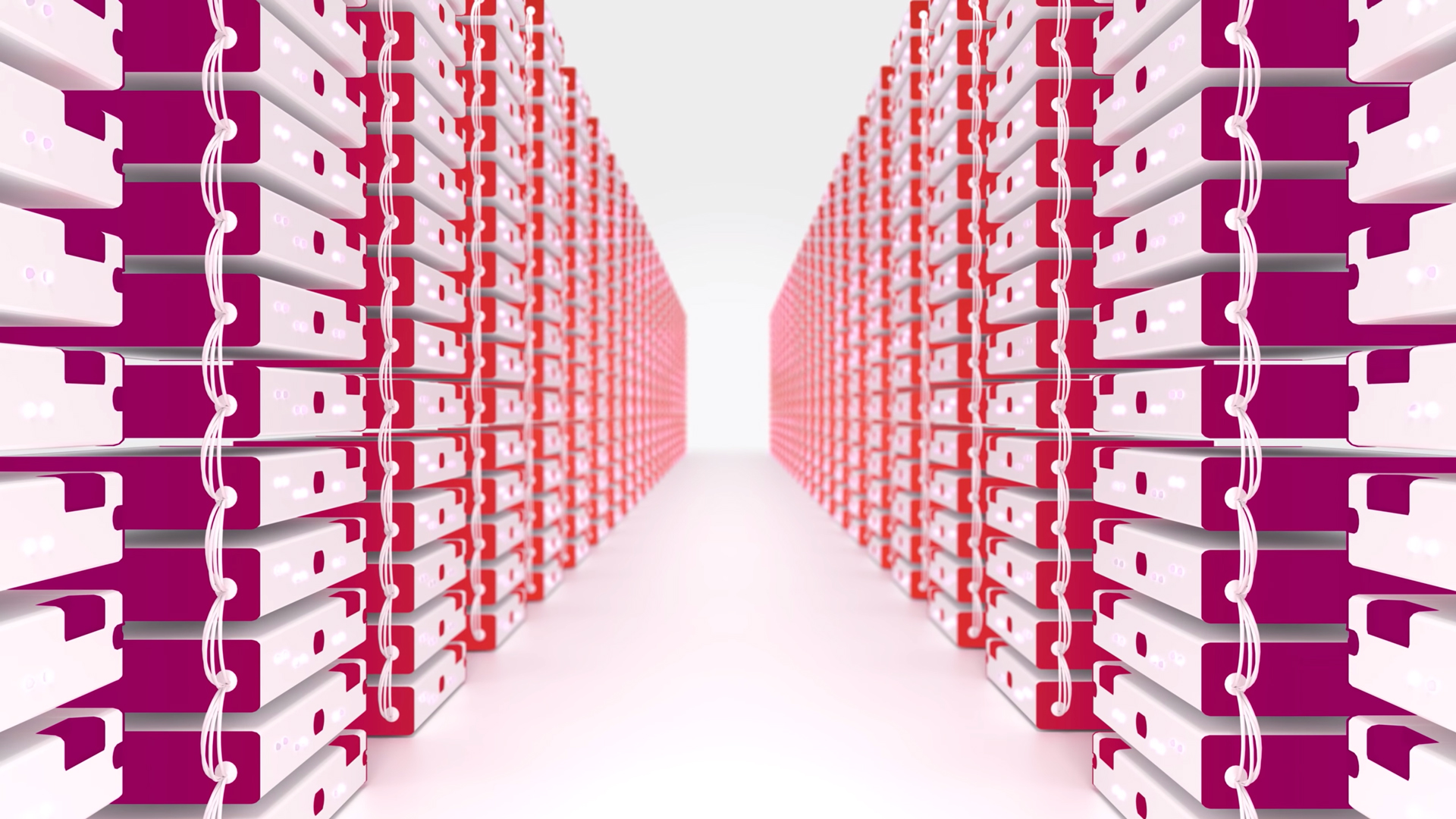

Google has to pay developers to be on its platform. Not because it's bad – it isn't – but because the audience for Stadia is still so limited. For every player with the internet speed I recently gained, there's another with the treacly connection I suffered before. 5G remains a luxury commodity practically everywhere in the world. It is, in fact, being partially rolled back in the UK, making streaming tech even less viable. Just as Oculus and CCP did with VR, Stadia has jumped the gun on the future.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

That, ultimately, is why it will struggle to succeed – and why I suspect Xbox will instead. Microsoft, like Google, has got cloud gaming up and running. But rather than push a dedicated service on consumers who can't yet take advantage, it's building the infrastructure in advance.

Stadia and xCloud go head-to-head

The first step has been to turn its business into a subscription. Immediate sales of the Xbox Series X and Xbox Series S, it would appear, are less important to Microsoft than selling subscriptions to Xbox Game Pass Ultimate. It's a package that gives you access to hundreds of games, bundles in access to EA Play, and exclusives from all of its first-party studios – not nothing when that list includes Double Fine, Obsidian, and the current custodians of Fable, Forza, and Halo.

The crucial point is that Game Pass already has the shape of a Netflix. When the time comes for players to switch to streaming – whether that's next year, or in five years' time – the foundations will already have set.

Game Pass Ultimate is already exploring its integration with cloud gaming, through Microsoft's xCloud initiative. It's restricted to Android phones, and I imagine at some point Microsoft will want to create a smart screen app, or sell a device that allows streaming direct to televisions, like the Steam Link. But there's no rush; like Stadia, the Steam Link came too soon, and Microsoft will be keen to bide its time.

Unlike much of the industry, Microsoft has had to learn patience. It has, after all, jumped the gun before. When first announced, the Xbox One required a daily internet connection to function; consumers found the idea restrictive, and the backlash saw Microsoft walk back the decision, ceding ground to Sony and the PS4 in the process. Today, the console as originally announced wouldn't seem nearly as punitive – the digital-first landscape Microsoft envisaged has now come to pass. It merely needed to wait for the world to catch up first.

It would be foolish to predict precisely when cloud gaming's day will come, just as it would be unwise to suggest the year of VR's eventual ascension to the living room. But when it does, victory will go to the companies who have arranged the furniture, ready for when players feel able to take a seat.

Looking for more information on each of the major streaming services? Here's our guide through the complex world of game streaming services as we look at Google Stadia vs Project xCloud vs PS Now.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.