Cannes 2018: Martin Scorsese talks 1974's Mean Streets and his upcoming Netflix movie The Irishman

We chat to Martin Scorsese about his next gangster epic from Cannes

With Mean Streets showing in the Directors’ Fortnight strand 44 years after it made an international splash playing in the same section of the Cannes Film Festival in 1974, Martin Scorsese graced the stage for a post-screening Q&A. His rat-a-tat delivery was lent a staccato quality by the interpreter’s need to jump in mid-sentence for the benefit of French audience members. No matter: motormouth Marty still managed to whizz through the key events in his formative years that triggered his rough-hewn, energetic tale of hustling hoodlums in Little Italy, and to discuss the key themes of spirit vs flesh, good vs evil, business vs family.

From there Scorsese accelerated into discussing other notable pictures in his exceptional career, and even touched, albeit all too briefly, upon his long-gestating $100m gangster epic The Irishman, starring old chums Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Harvey Keitel, and some untested whippersnapper named Al Pacino. With filming concluded, it is due to drop on Netflix in 2019.

Mean Streets, in 1974, was your first visit to Cannes. How did it compare to your subsequent visits?

Cannes was the international platform for Mean Streets, a film I didn’t think would even get distributed. My visit was almost the best time, in terms of anonymity. And trying very hard to change that! I was able to go from table to table on the Croisette and meet actors, directors, and so many others. It was still a period of discovery, not just for new filmmakers but older, neglected filmmakers.

The film is very much grounded in your own youth…

I was growing up in, as far as my perception as as a child and a young adult, a very dangerous place, populated by some very tough people and some very good people. And some [who were] both: bad and good. Mean Streets was basically, ‘How does one lead in a good life in a world that is not?’

Characters battling for their souls would become your raison d'être…

Over the years I’ve been more attracted to those characters. And particularly male relationships, and brothers. I have one older brother, and a lot of that is reflected. I feel more comfortable with that material and can explore the characters better. Ultimately, it’s a matter of, ‘If you live in a bad place and behave badly, are you really intrinsically bad? Or is there good in you?’

Did you see these people in your own house, in your own neighbourhood?

I saw my father and his responsibility to the family, and to others in power. Responsibility and obligation. Where does obligation end, if it should, at all? A lot of the film is what I was living at the time but it really took me years to understand that it’s really about my father and his youngest brother; until the day they died – and his younger brother died only a few months after him – my father was still doing [him] favours, and my mother was saying, “Don’t do it, don’t do it.” [His younger brother] was always in trouble, always in and out of jail. But I loved him. He was amazing.

Mean Streets starts with the voiceover: “You don’t make up for your sins in the church. You do it in the streets…”

I was very influenced by one priest who was a good teacher, mentor. Not in class but a street teacher, from when I was 11 to 17. He was the one who made me realise that we have to go for more. Not settle. It’s more this concept of love and compassion. And I had to do it because the alternative was violence and murder. That’s what I saw around me. Ugliness. And some beauty. What he taught us was really remarkable.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Yet the ugliness is often packaged within humour, isn’t it?

Humour is so important. So much of my life, the comedy was there. Comedy-tragedy. Humour is a seductive way of making people who are psychopaths or sociopaths very funny. It’s the Italian style of entertaining, and liking an audience.

You don’t need to make an outright comedy because you’re most violent movies are full of bilious laughs…

I thought After Hours was a comedy. But a nightmare. A very funny nightmare. It was like that film Mother!, in which people keep coming in the house. She tells her husband “Get rid of them!” “No, it’s gonna be fine.” “Fine! They destroy everything, eat the baby. This is madness!” I liked it. I had a dream like that two nights ago. I couldn’t get out. People kept coming in.

The King of Comedy is certainly no laughing matter…

I was going through a difficult time. Each day I had to face it because I was pouring my own unravelling into Rupert [Pupkin, the crazed wannabe comedian played by De Niro]. I hardly moved the camera on that picture. Maybe once or twice. It was claustrophobic and disturbing.

Talking of moving the camera, how much of your aggressive shooting style is pre-planned?

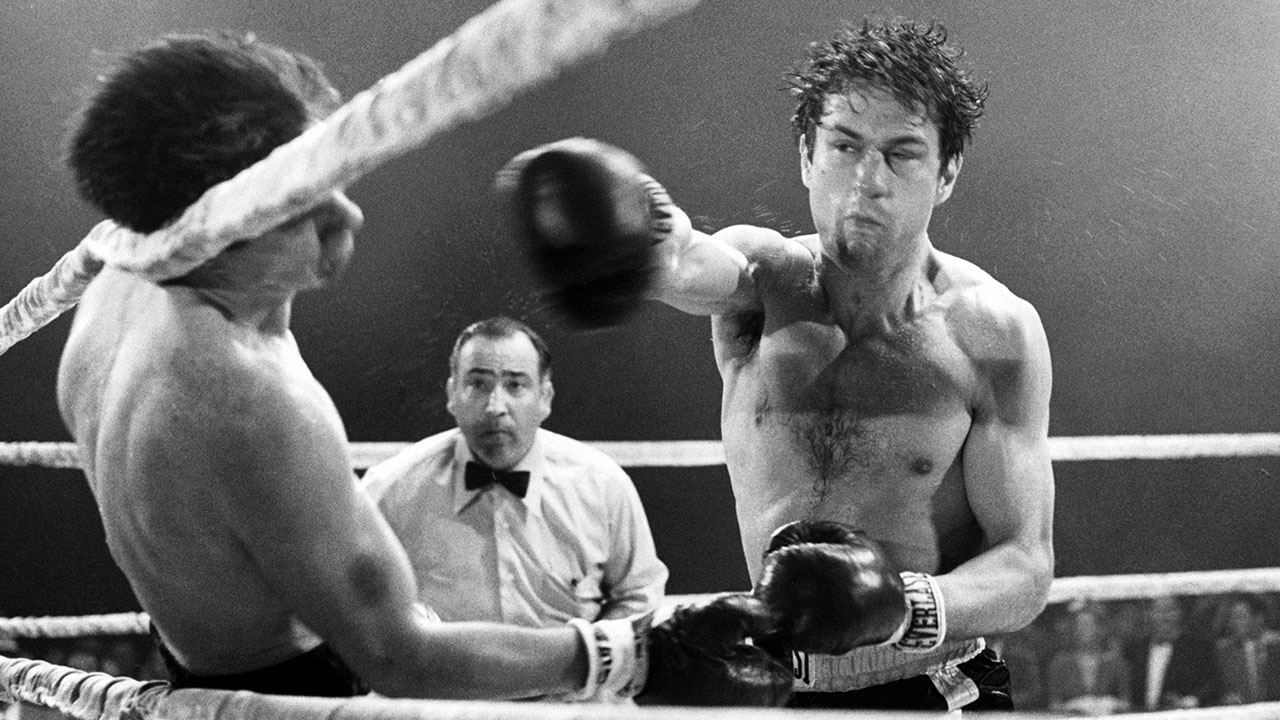

All the boxing scenes in Raging Bull were designed on paper. We shot all the fight scenes first. Ten weeks. It was supposed to be three [bellows laughter]. All of Taxi Driver, all of Mean Streets. Primarily just because of the short schedules. I needed drawings to show to the cameraman and say, “This sort of thing”. To explain how I saw it. At the same time, my heaviest influences were the films of Elia Kazan in the ‘50s, where you can have a two-shot, and hold the camera, and it’s just the people in the frame. John Ford would hold the camera on two actors. So I’ve stopped doing drawings and notes for certain dialogue scenes. I need to work with the actors, be on the set. See the location.

Do you storyboard less these days?

In this latest film [The Irishman], there are so many scenes – almost 300 scenes – and it was hard to get to location, but when I got there I’d work out the angles. But it was primarily bringing out the actors and making the shoot comfortable. That became the mise-en-scène, for me. And that has a lot to do with On The Waterfront, East Of Eden, Wild River. Beautiful films. But Taxi Driver, Mean Streets and Goodfellas were all drawn.

Do you discover scenes on the day?

Some scenes are panic! You’re suddenly there and you hadn’t planned on something and you have to do it. There’s an excitement, a panic. And we hope for good accidents. “Show me something” [looks to heavens] and something happens. For example, a good accident is “Are you talkin’ to me?” [De Niro improvised Taxi Driver’s] famous monologue]. I’m not gonna stop that. But we were being attacked because we were so far over schedule. And also [GoodFellas’] “You think I’m funny?” That was a planned accident. Joe [Pesci] said, “I’ll only do the movie if I tell you a story and you put it in the film.” He told me the story and I said, “I got it.” I didn’t even put it in the script but I knew where we could shoot it. I only shot it with two cameras and squeezed it in with a day we were shooting something else. We had rehearsed it, so I felt very secure.

Read our verdict on Paul Dano's Wildlife from Cannes Film Festival 2018.

Jamie Graham is the Editor-at-Large of Total Film magazine. You'll likely find them around these parts reviewing the biggest films on the planet and speaking to some of the biggest stars in the business – that's just what Jamie does. Jamie has also written for outlets like SFX and the Sunday Times Culture, and appeared on podcasts exploring the wondrous worlds of occult and horror.