Duck and cover (and wait ten seconds)

Weve all been there before. You find yourself on the ground, wounded, unsure of whether or not youll ever have the strength to carry on again. Youve just taken a damaging sword blow/gunshot/super punch/whatever, your vision has become disoriented, and now you have to find a way to get yourself healed before that last ounce of life is squeezed out for good. So what do you do?

Well, if youre in a video game, nothing. Just sit there for a little bit--youll be okay. Thats because more and more modern games have adopted the regenerating health mechanic, which does away with the health packs of yesteryear and encourages players to lay low to regain their energy. And with Call of Duty: Black Ops II--the latest from the franchise thats known for popularizing the trend--hitting store shelves, weve decided that its time to take a look at the history of this totally unrealistic thing many games do. So join us, and dont worry if you get hurt in the process.

Hydlide and the beginning of the trend

Many gamers may think that regenerating health is a relatively new phenomenon, but the reality is that the mechanic is almost as old as video game consoles themselves. It all started with the action-RPGs and rougelikes of the early 1980s, the kind of games that would best be characterized by such classics as The Legend of Zelda and Crystalis.

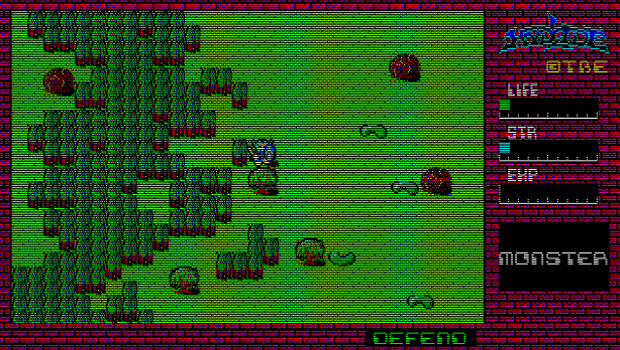

More specifically, the earliest known example of the recharging health trend can be found in Hydlide, a mediocre 1984 PC RPG that was initially released only in Japan. Five years later it would come to North America as Hydlide Special for the NES, introducing Westerners to the first, and simplest, implementation of the mechanic. When protagonist Jim--Hydlide wasnt the most imaginative game--stood still, his health and magic slowly refilled. Sure, it wasnt complex, but it was an undoubtedly significant milestone for its time.

Regenerating health becomes a genre standard

Hydlide, while not a particularly good game overall, did make a number of innovations in RPG design that would go on to influence many other (and better) entries in the genre. Some of these included a quick save system, the ability to switch between attacking and defensive positions, and, of course, the aforementioned regenerating health system.

With regards to that last one, perhaps the most recognizable series to ape the recharging health mechanic was developer Falcoms Ys franchise, which began with 1987s Ys I: Ancient Ys Vanished and has continued with multiple installments since. Health in that game would only regen in overworlds and defeated boss rooms, but the fact that it was even included in successful titles like Ys at all helped make the trend a recurring one. Regenerating health would primarily remain exclusive to action-RPGs for the next decade or so, and its legacy still carries on in the genre today through games like Fable and Mass Effect.

Faceball 2000 recharges health with a smile

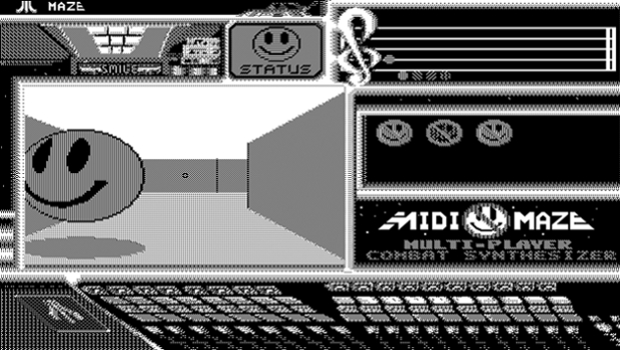

If you had to think of which genres to associate with regenerating health, chances are that first-person shooters would be the first to come to mind. And while RPGs may have staked their claim to the mechanic first, a handful of retro FPSes did lay the foundation for Halo, Call of Duty, and the bajillion other modern shooters that adhere to the system today.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Chief among these was MIDI Maze, a popular 1987 puzzle-shooter for the Atari ST that was later released as Faceball 2000 for the Game Boy and Super Nintendo. It tasked players with making their way through various--you guessed it--mazes, shooting down walls from a first-person perspective while taking out teams of opposing players. MIDI Maze has been lauded by many for essentially introducing deathmatches to the gaming world, but it also sported a regenerating health system that let players regain hit points by keeping safe. Like Hydlide, MIDI Maze wasnt a particularly amazing game, but its daring design choices deserve to be recognized.

Halo brings regeneration to the massessort of

Everyone remembers Halo: Combat Evolved. The Xboxs killer app changed the trajectory of the FPS market for good when it was released in 2001, as it introduced a number of subtle changes to traditional shooter design and definitively proved that the genre could thrive on consoles. From those first steps within Master Chiefs stoic green armor to he and Cortanas final escape from the Pillar of Autumn, well never forget our initial adventure with the famed Spartan. And, of course, well never forget his magically regenerating health either, right?

Wrong. While many credit the game with popularizing the mechanic, the fact of the matter is that Halo: CE didnt even feature regenerating health at all. Instead, it gave players regenerating shields, while utilizing a more traditional health system underneath. The next two installments in the franchise added full-blown health regen, though, and while both Halo 3: ODST and Halo: Reach reverted to the originals non-regenerating ways, Halos unprecedented commercial success led to many, many studios borrowing as many of the series traits as they could, recharging health included.

The Getaway lets players get away with getting hurt

Regenerating health as its primarily recognized today--the kind where players can simply hide until all their boo-boos go away--can best be traced to The Getaway, a 2002 open-world action title from now-defunct developer Team Soho.

Gamers will remember The Getaway most for the way it allowed the protagonist to heal, though. As you can probably infer from his name, Mark Hammond is no superhuman or hardened soldier. In fact, hes just some guy from London. But, somehow, he has the ability to shrug off bullet wounds by simply leaning against walls. Yep, thats it--just hide behind a wall and everythings gravy. The Getaway didnt have health bars, instead conveying damage through visual cues like making Hammond walk with a limp or having his suit become increasingly soaked in blood. When those cues became overbearing, players could then get in cover, take a breather, and get back in action as if nothing ever happened. This design should sound familiar to anyone who has played a typical shooter or action game lately, and with good reason: The Getaway was a pioneer.

Call of Duty solidifies the new era of health

Of course, wed be remiss not to mention perhaps the most recognizable user of regenerating health: Call of Duty. Like Halo before it, Call of Dutys elimination of all things health pack actually started with its second installment. Since then, though, each of the seven annual sequels that have followed have taken the aforementioned approach of The Getaway, using context clues like red screens and heavy breathing to indicate the player-characters life.

Those widely-recognized prompts have trained millions of gamers worldwide to know when to stop what theyre doing, even if its just for a second or two, and give themselves time to heal. This mode of recharging, where resource management and tactical movements are largely downplayed on standard difficulty settings, has helped make CoD more easily digestible than most other shooters on the market. And as we all know, being more easily digestible usually means being more marketable to the masses, for better or worse.

Regenerating health begins to mutate

Once health regen became a standard feature in the shooters and action titles of the early-to-mid-2000s, developers began to tinker with the relatively simple healing ways of The Getaway and, eventually, Call of Duty. The results were a handful of games that still featured the regenerating health concept, but added a few varying twists on top of the formula.

One of these twists can be termed the limited health regen, where a players health will only refill up to a certain point if it falls too low. So, say a particularly tough battle drops your health down to about five percent. In games like F.E.A.R and Prey, ones health bar would only refill to somewhere around the 25-percent mark, leaving it up to the player to get themselves back to full health with medkits. This kind of system does make some concessions to the standards of today, but not so many as to remove all semblance of careful management entirely.

Health regen gets fragmented

Another variation of regenerating health that quickly became popular was something well call the fragmented health regen. Like a slightly less taxing version of the limited system, the fragmented health recharge divides (or fragments) the players health into multiple segments.

Other ways to heal are unveiled

The varying ways developers have worked around the regenerating health mechanic dont end there, though. Just Cause 2, for instance, features a percentage based restorative system, where ones life bar is filled just enough to keep protagonist Rico moving from locale to locale. Gears of War and Army of Two, on the other hand, allowed the player to die if enough damage was taken (and they didn't heal in time), but let them come back to life with a quick resurrection from an ally.

Deus Ex: Human Revolution--much to many longtime fans dismay--sported an overcharge system, which brought Adam Jensens health to full a few seconds after taking damage, but could also double his life through certain items. Even the healing fountains and regen spells of RPGs like Final Fantasy can technically be considered a variation of the system. There are quite a few other types too. Point being, this stuff is absolutely everywhere.

Why we heal this way

Now that we know when and where gamings regenerating health fetish came about, its worth exploring why its become the predominant way of healing in video games today. To sum, health regen makes things simpler, in almost every facet of a game. Resources dont need to be meticulously managed. Single-player and multiplayer battles always take place on a level playing field. Cover-based mechanics are made more prevalent. And, since health packs no longer need to strewn across random, secret areas, level design is made simpler.

Regenerating health makes everything easier, and makes games require less effort on the part of the player. As youd expect, this has its benefits and deficiencies. Those who long for the scrupulous, thorough games that put the player in charge of every aspect of its events will deride the system for streamlining too much. But those who want a tighter, controlled, and perhaps more scripted experience will be delighted to see such games take them through their journey. Sometimes people just want to duck, shoot, and have fun, after all. Of course, theres a commercial aspect to all this too, but you probably already knew that.

Put away that medkit, son

And if you're looking for more historical musings, check out the history of Call of Duty box art and the complete history of Mario RPGs.